Haley Jane Samuelson: Year of the Beast

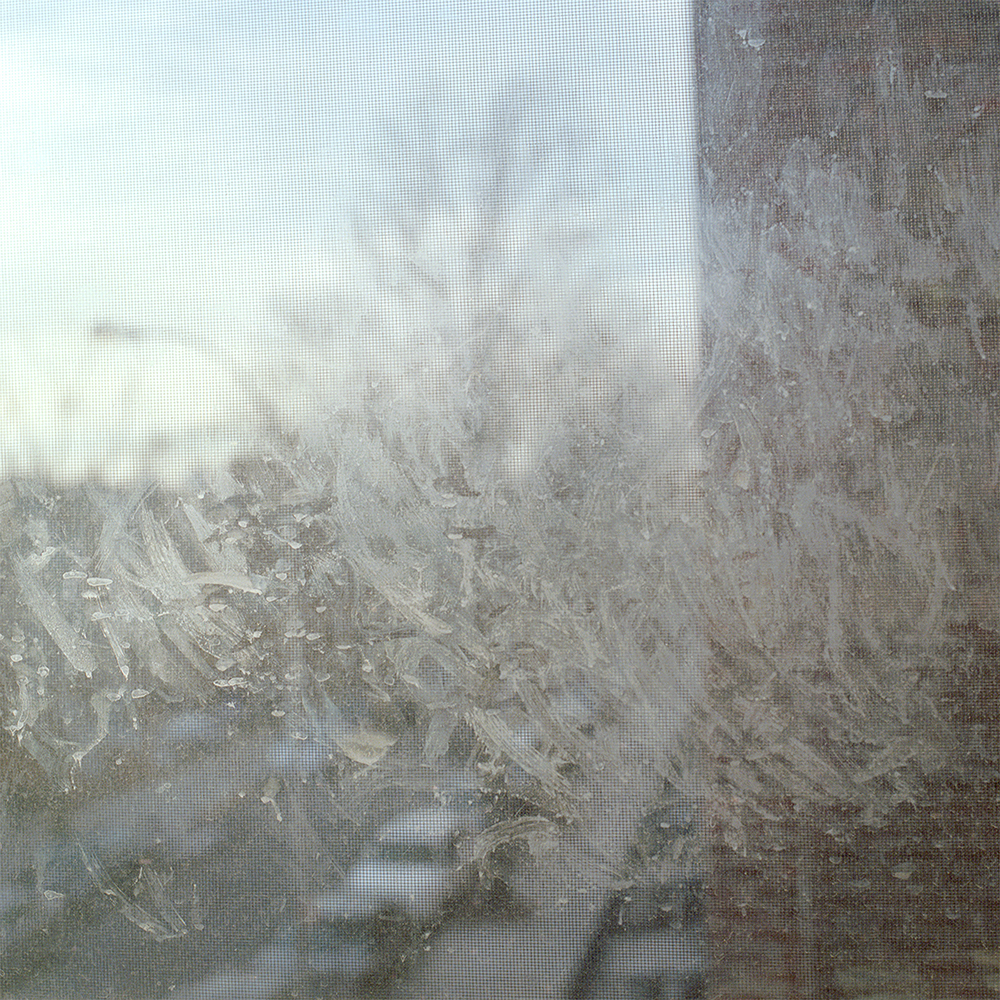

Haley Jane Samuelson’s Year of the Beast is quite the coming of age story, though not so much in the traditional sense. Here is a body of work not revolving around becoming an adult or the process of finding the one and only, but establishes itself later in life in a place that is reserved for the achieved, the settled, the people that have “figured it all out.” After living in New York for ten years, Samuelson and her husband relocate westward to Colorado to live with family. What follows are the stories and depictions of two newlyweds having to make unexpected changes in a time they are meant to be settling down. These photographs are their daily intimate lives, caught in ever-shifting light and liminal space, and paired with narratives that provide a little more insight into their transition.

Haley Jane Samuelson was born and raised in Denver, Colorado until the age of thirteen when her family relocated to Amsterdam, The Netherlands. It was there she first fell in love with photography. After ten years in New York City, she recently relocated back to Colorado where she acts as chair of exhibitions at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center. Her work has been shown at art fairs across the globe, including Photo LA, Photo Miami, and Art Basel. In June 2009, she had her first NYC Solo Show, “Another Room,” which was well-received, gaining some publicity, most notably a short review in The New Yorker by Vince Aletti. A second solo show followed at Housprojects Gallery in 2012. She is now represented by Charlet Photographies in France and was featured at the most recent FotoFever festival in 2015. Her work has been published in several international magazines including Zoom Magazine, Oxford American Photo France, and Korea Photo+ among others.

Year of the Beast

Following my marriage to my husband, Michael, I was inspired to create a body of work documenting our lives together as husband and wife and the nuances of our day-to-day experiences. While admittedly ordinary and uninteresting in their premise, I had hoped images would evolve into a thoughtful portrait of intimacy and the merging of two lives. Just months after beginning the project, however, my husband and I, facing growing economic hardships, were forced to make a difficult decision to leave our Brooklyn home of ten years and move to Colorado to live with my parents. The photographs in Year of the Beast attempt to document our experiences, as we to come to terms with the illusion of adulthood, surrender our notions of independence and try to achieve some balance between dreams and reality.

Capturing the mundane, yet private moments of everyday life, the images are meant to resemble personal snapshots. The mostly square format along with the warm, nostalgic color-palette, are a deliberate allusion to the visual aesthetic of Instagram and the cultural need to filter and manipulate reality through the act of image making. While the images from the Year of the Beast are indeed trivial and lighthearted in nature, the accompanying text portrays a more realistic, less optimistic, story. In this way the images go beyond the obsessive, indiscriminate chronicling found on social media sites to question the nature of consensual reality, acting as sort of a visual compromise between who we want to be, and who we really are.

In a way, the act of photographing becomes an act of reconciliation and acceptance, as my husband and I struggle with the changing nature of our parents’ American Dream and begin to forge our own. Knowing that our situation is not unique, I hope that the work I create can act as a microcosm, representative of a larger part of my generation’s experience with the trials of young adulthood in the face of a changing economic, technological and environmental landscape.

“Listen,” he said. “We’re tackling all the hard stuff this year.” Well, he didn’t so much say it as type it. These days, most of our conversations happen online. It is August, and he is at home and I am at work. Only I am not working. I am staring at a running feed of images of people I barely know crawl across my screen.

Mostly babies and weddings and poorly lit images of barbeque chicken that, next to the babies, remind me a bit of afterbirth. I don’t know what he is doing. He is trying to reassure me that everything is going to be all right, even though he doesn’t have a job and my job makes me miserable.

“If you say so,” I respond. I tell him about the barbeque chicken.

“Gross,” he says.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“Multitasking,” he says.

I run across an image of a girl I went to college with. She is breastfeeding. She is also taking a shit. She is breastfeeding her pink and pruney, barbeque covered baby while also taking a shit. She is photographing it. She is proudly posting it for the world to see. Below, the caption reads:

Multitasking, 53 Likes.

Everyone is growing up and having babies. I see them online. Little pixelated fetuses lining up, one by one into infinity, in black and white, across my screen. As if I have some sort of live feed to every ultrasound machine within a 500-mile radius. I don’t know why people post them. They look more like inkblots from a Rorschach test, than they do babies. When I am bored at work, or sometimes at home, I like to look at them and see if I can find any hidden meaning locked within the images.

I see our bleach-stained sheets; the bruised banana likeness of my coworker’s regrettable tattoo; the bearded face of the guy on the subway I spotted playing with his pecker; that green and grey argyle sock that went missing in the laundry last week; Sunday night’s leftover spaghetti (but somehow the meatballs are missing); and a portal to another realm. Or maybe just New Jersey. Jesus Christ, I see the fucking Holland Tunnel.

Nevertheless, I tell Michael that I want to have a baby some day. He says he does too. After all, it seems like a nice thing: A baby, a house, and a yard for our dog to run around in. Some day, anyway. For now it exist, like all things do, in some vague, ambiguous form. Another inkblot pooling slowly in the corner of my mind.

Michael doesn’t like kissing in public. I didn’t used to mind it, but now it makes me uncomfortable too. Sometimes we’ll hold hands and walk down the street, but it never last long before our palms get too sweaty or we have to part ways to avoid running into some cliché: The tourist stopping traffic to capture a selfie. The student with the clipboard lobbying for some cause they only half believe in. Or, the biggest obstacle of all, the family of five traveling in v-formation across the entire width of the sidewalk, like a flock of geese too tired to actually fly.

He’ll go one way, and I’ll go another. We’ll dodge them. Then we’ll come back together, if only momentarily, before it happens again. We weave in and out, down avenues and alleyways, a perpetually mutating double helix adapting to the ever changing pulse of this ugly city. Together, then apart, then together again. But we’ll never kiss. Not in front of these monsters. It is romantic as hell.

In another life we are two old men. We sit together at night, drink whiskey from the bottle, play card games and talk shit. Mosquitos buzz in unchanging flight patterns around our heads, landing only intermittently to feast on our calves or the back of our necks. Sometimes we are quick enough to swat them dead. Blood and guts spatter across our hands or on the kitchen table or high up on the wall, like tiny accidental Pollock paintings, or last night’s spaghetti nuked on high for too long in the microwave. And we just leave it there, because we are old men and old men don’t care.

It is nice not to care. Not about money. Or haircuts. Not about the war in Syria. It is nice not to worry about time; About the time you have left here on earth, or the tick-tick-ticking of some biological clock, the bomb in your brain or your heart or your ovaries. It is nice to sit in silence; To not talk about the weather, or about gentrification, the raise in rent, or the boy at work who eats his lunch too loudly in the cubicle behind yours. It is nice just to be; To not be post-grunge, or neo-punk, or bound by some feminist roots passed down to you by your mother’s, mother’s, mother. To be an old man. To cuss like sailors because we once were sailors and we’ve earned the right. Or maybe, to be a mosquito. To forsake all pretense and go straight for the blood. Knowing that someday, you too will die as art on someone else’s wall.

Michael always believed that given enough time, and the right circumstances, we would one day make something so great, that it would transport us into eternity where we could live forever.

Michael believed a lot of things. That our hard work would pay off. That what we did, mattered. That if he just screamed loud enough, the universe might hear him and, charmed, would stop its ceaseless motion to return his call. We would take our place amongst the canon of art school heroes, like Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, who everybody knows, were once just kids themselves. Michael believed that we were meant for greatness. He said it was the way it had to be. There was no alternative. The rest was just shit and masturbation.

I wonder now, if we fixated on all the wrong things. On my birthday, Michael bought me a bucket hat and a pair of aviators. He took me on tour of all the apartments Hunter S. Thompson had ever lived in during his time in New York City. Of course we couldn’t go inside, someone else lived there now, but that didn’t matter. Standing on Thompson’s old street, looking up at his would-be-window, I knew Michael was right. The dream was better than anything else I could have ever imagined.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025