Lisa Elmaleh: The States Project: West Virginia

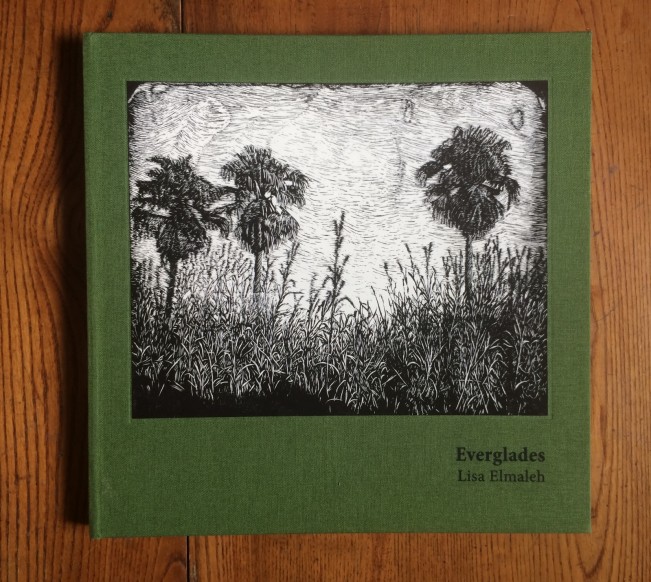

I first was exposed to Lisa Elmaleh’s wonderful work when I received her book, Everglades, in the mail. Published by Zatara Press, it is stunning in its combination of wet plate capture of the everglades with a small book of text, all bound in beautiful green linen.

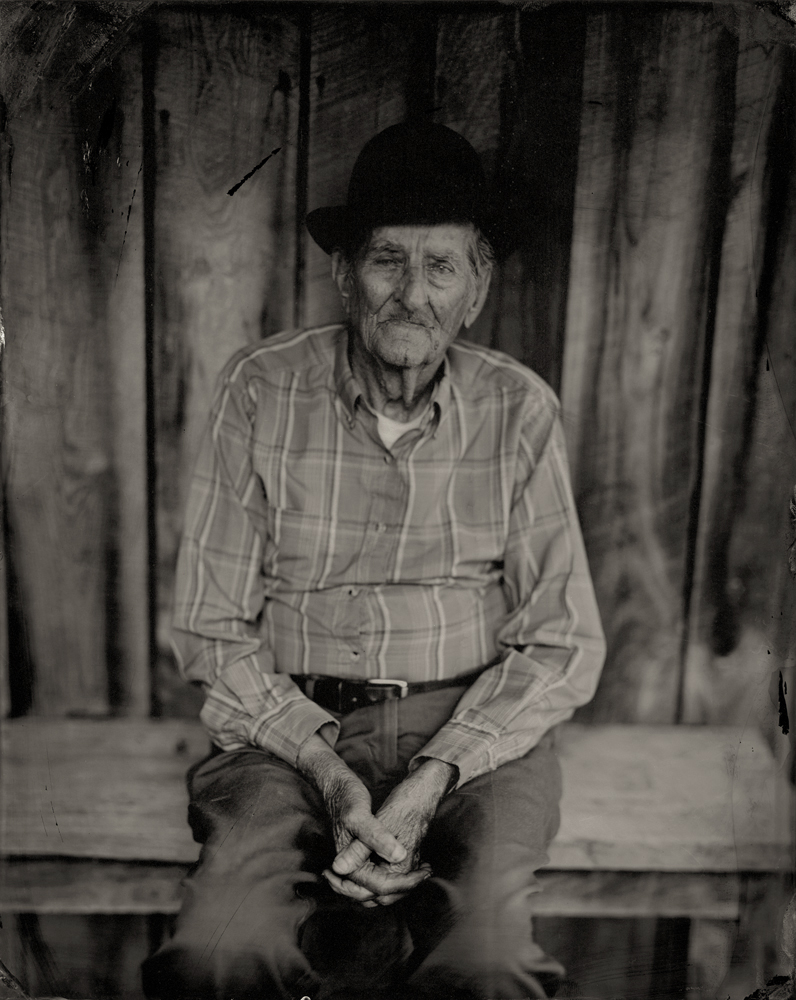

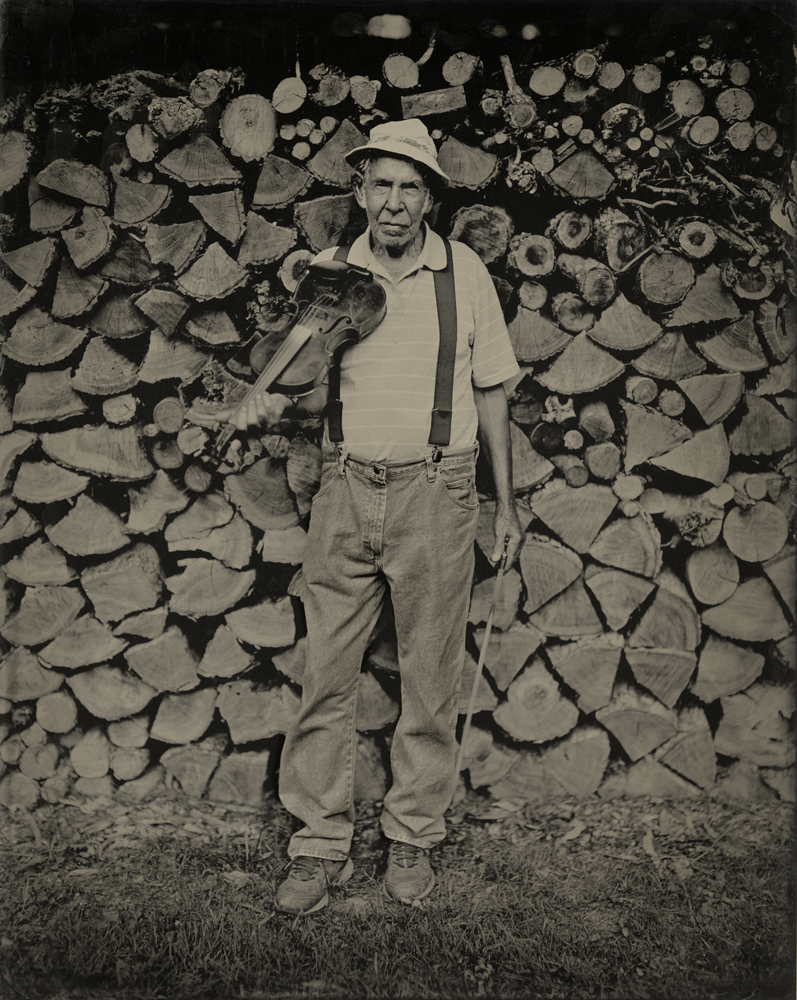

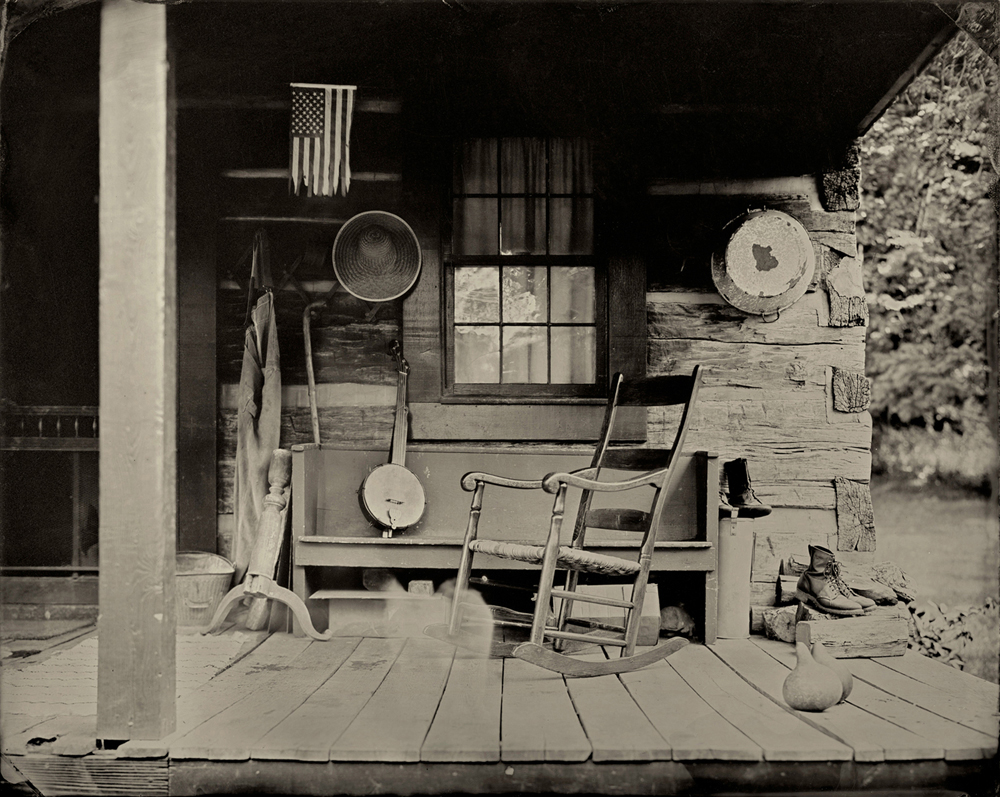

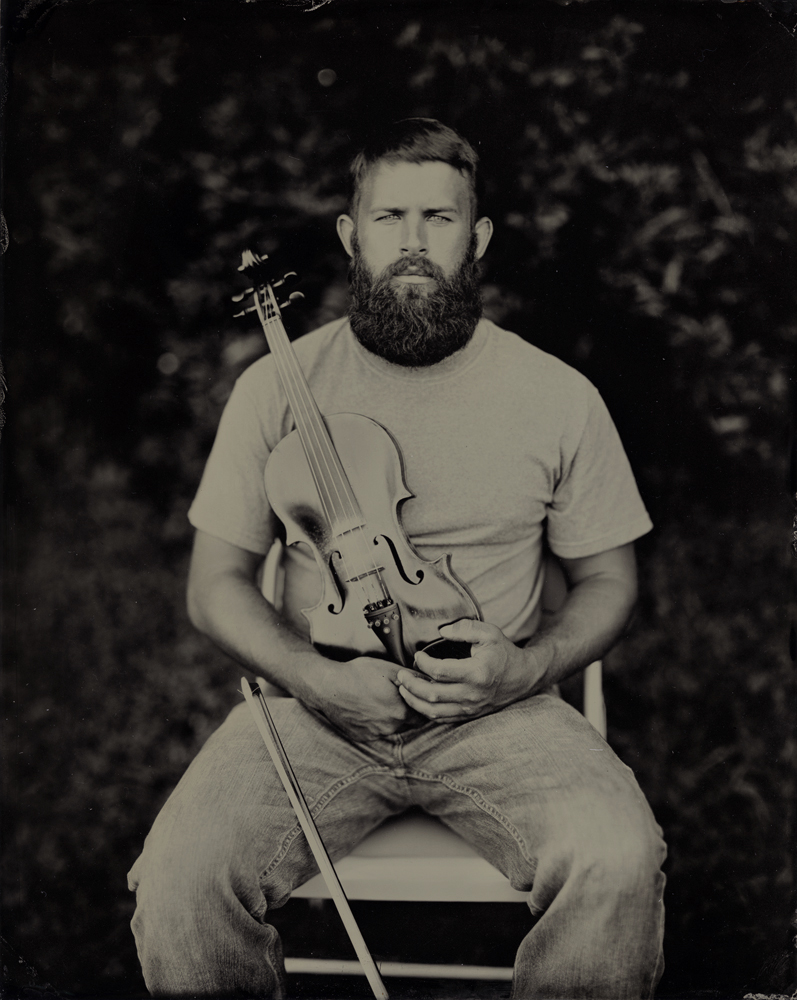

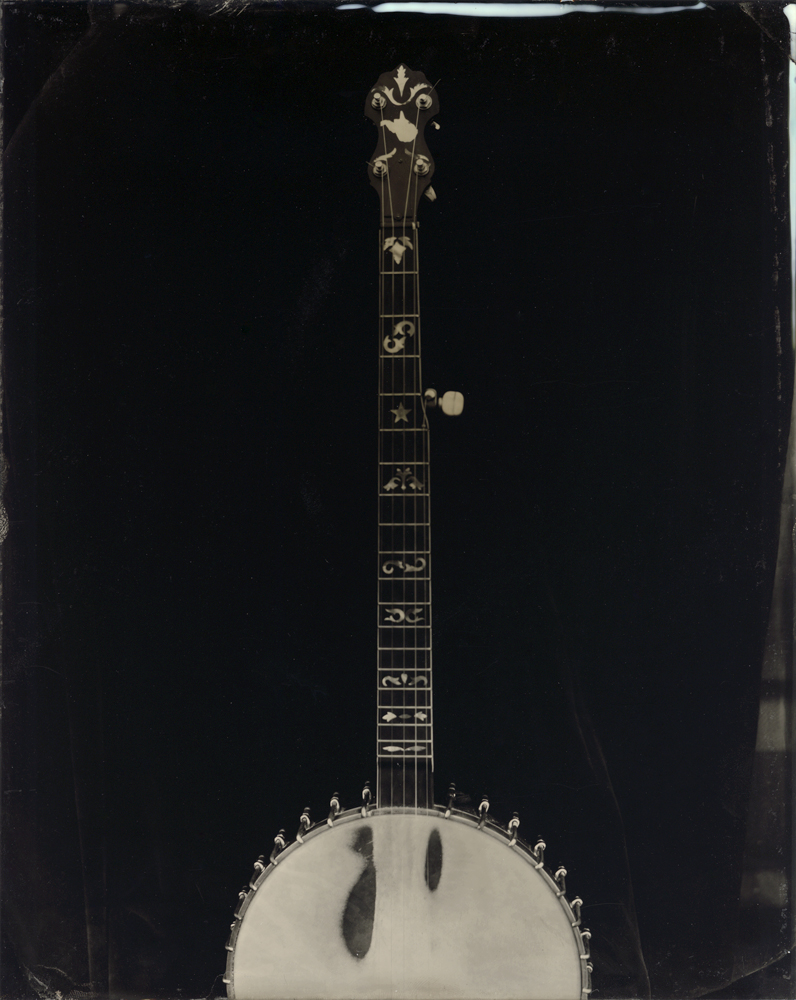

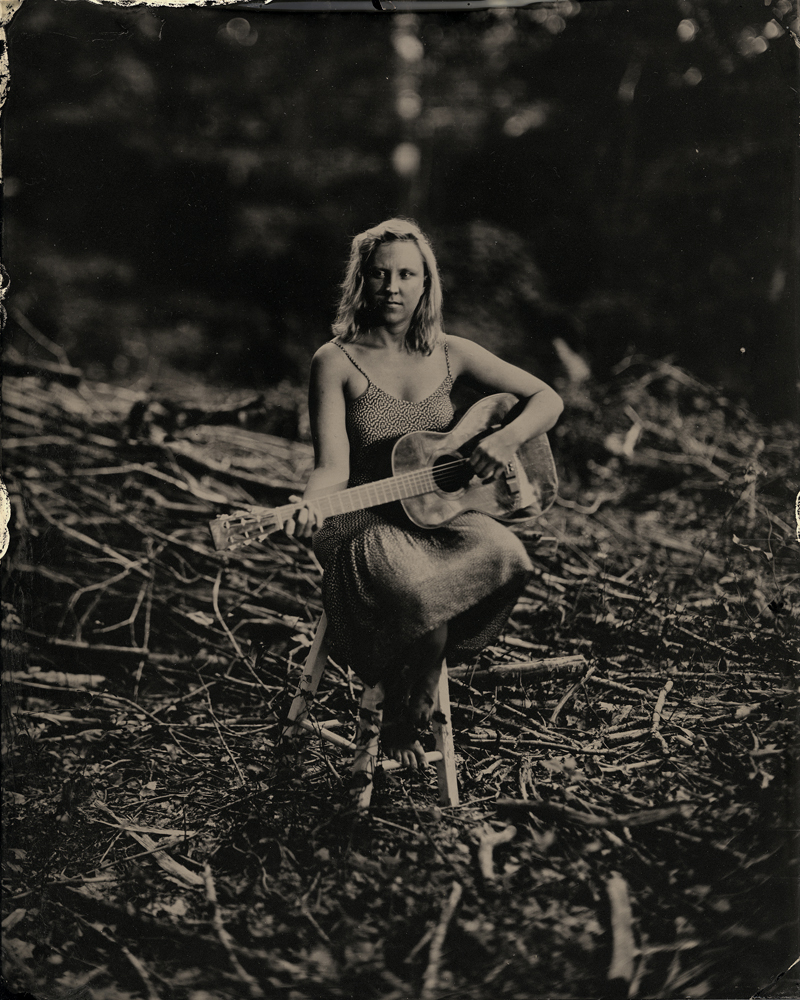

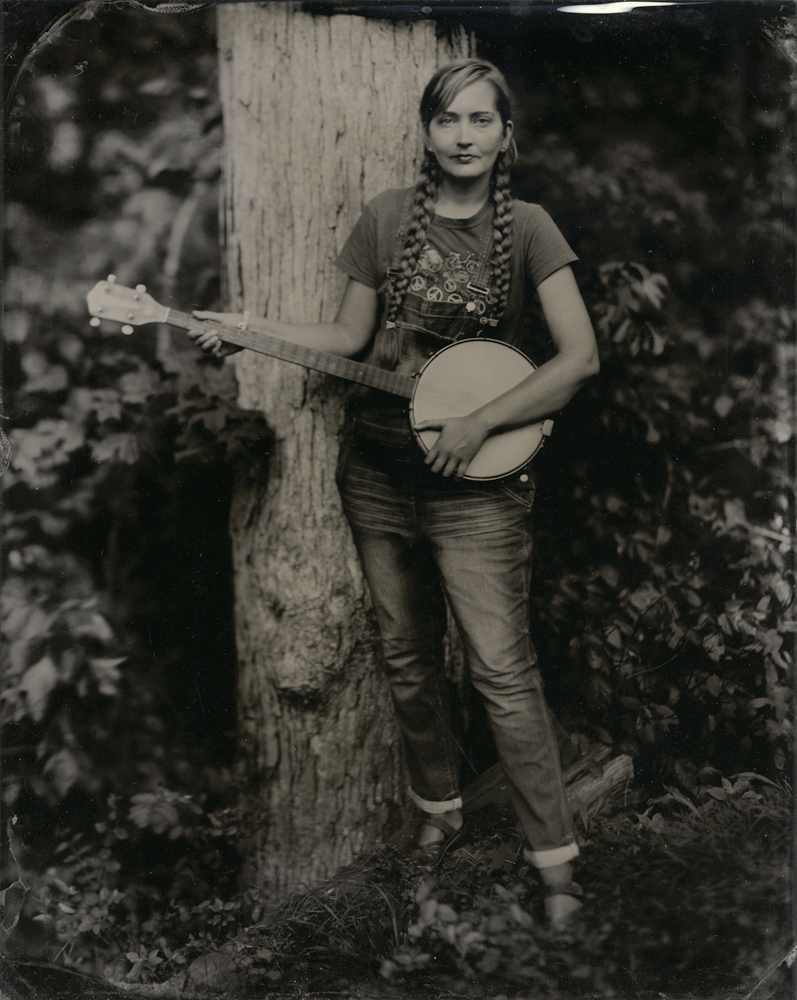

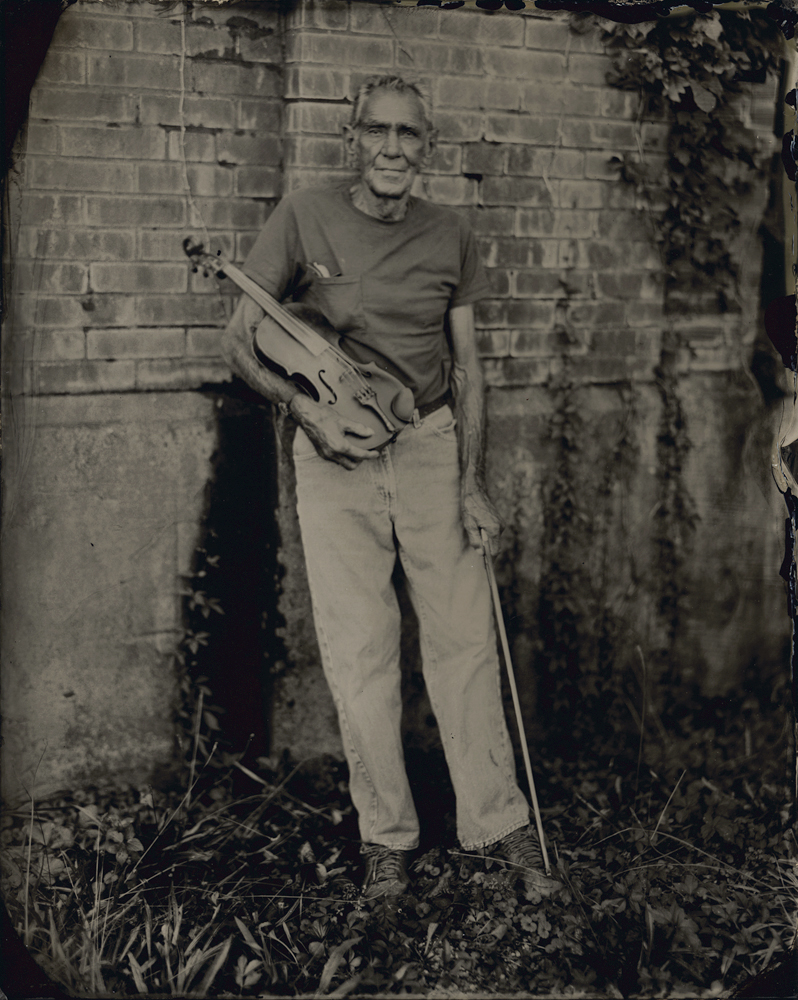

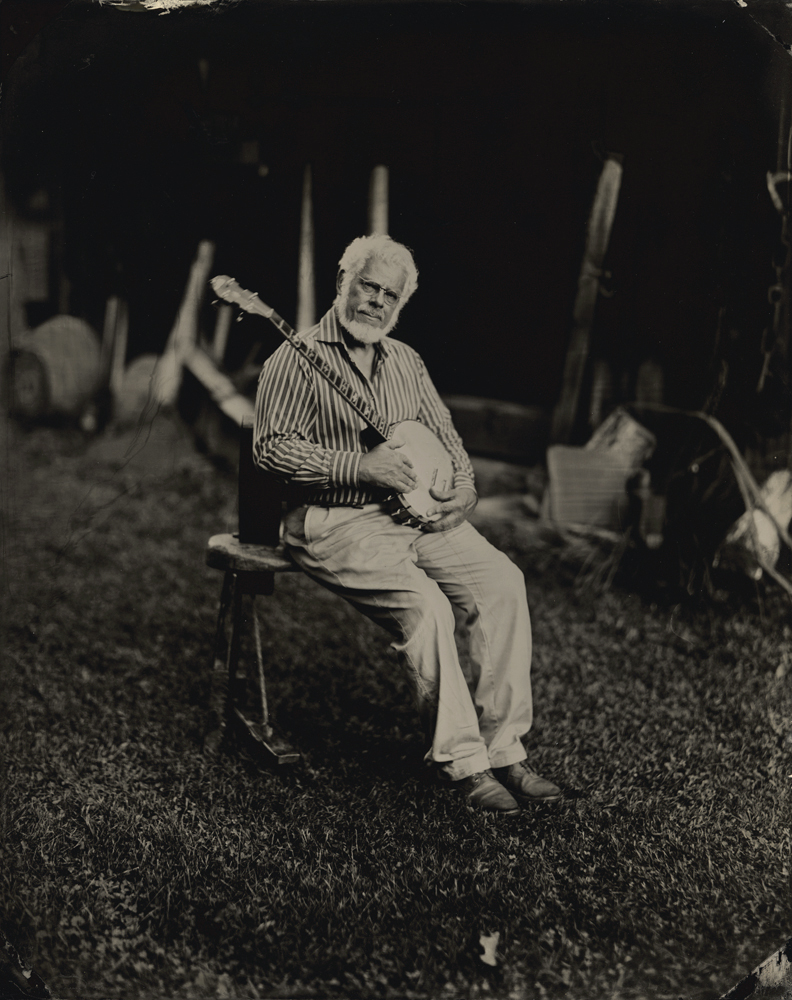

I’m thrilled to have Lisa as our West Virginia States Project Editor, as she has spent the last several years growing West Virginian roots. Her project featured today, American Folk, is what brought her to understand this part of the country in a profound way, through music and back roads and long visits on porches. This series beautifully captures the people and instruments that are the sound track of the Appalachian mountains, and her tin type capture, the perfect way to give a nod to history and tradition.

Lisa Elmaleh’s work is an exploration of America. Using a portable darkroom in the back of her truck, or the darkroom at her West Virginia home, Elmaleh photographs using analog processes. Elmaleh is a West Virginia based photographer and educator, teaching at the School of Visual Arts and the Penumbra Foundation in New York City. She has been awarded the Aaron Siskind Foundation IPF Grant, PDN’s 30, the Ruth and Harold Chenven Foundation Grant, the Tierney Fellowship, and The Everglades National Park Artist Residency. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, most recently featuring her American Folk project as a solo show, The Lightness and the Dark at the White Room Gallery in Thomas, West Virginia, and her Everglades project in a group show, Imaging Eden: Photographers Discover the Everglades at the Norton Museum. Elmaleh’s work is in the collection of the Norton Museum, the Ogden Museum, and other private collections.

American Folk

Traditional American “old time” music has been a large part of my work. The sound of the banjo, the fiddle, lyrics about working, about love, about the land – these tunes and songs were inspiring to me as I worked, as I listened while I drove around in the landscape photographing, or while I spent time in the darkroom.

Old time music resonates in and around the Appalachian mountains. The music is passed down from generation to generation, and largely played as a community. The music can be found on porches, in living rooms, at festivals, or dances. A variety of instruments are used – banjo, fiddle, guitar, upright bass, hammered dulcimer, mandolin, mountain dulcimer. The process of my travels and finding musicians to photograph is organic and collaborative.

The photographs I create are tintypes. I travel out to the homestead of each musician, and spend a full day or more with each musician, documenting their likeness, their instruments, and the landscape that they reside in. Each 8×10 tintype plate is hand coated, exposed in a large format camera, and developed on-site in a small cardboard darkroom in the back of my pickup truck. Each plate takes approximately twenty to thirty minutes to create. The slow process allows me to spend time with each musician, getting to know them, and getting to know the land in which they live. The tradition of American folk music echoes in the historic nature of the process I am using.

After growing up in Florida, living in Brooklyn for ten years, why West Virginia?

I moved to West Virginia in 2014.

Or, more specifically, I moved to Paw Paw, West Virginia in 2014, a town of a little over 500, from New York City, a town of a little over 8 million. There were a lot of reasons for this. I am lucky enough to be a photographer, and my work brought me here. The home I live in now is a cabin that I rent, very reasonably, from dear friends, musicians who I met through old time music. I had never lived in a place that felt quite like home – West Virginia, however, felt like home, and I guess that is hard to explain. I’ve given up trying to explain, because I am home.

I started photographing old time musicians, who play traditional music from Appalachia, in 2010. It was through the old time community that I found myself jogging to and fro in the state of West Virginia, and all over Appalachia, photographing and visiting and playing music with the musicians I was photographing. My photographs were tintype, which meant usually a day long visit or more, complete with me setting up my portable truck darkroom in various backyards and driveways, and sometimes sleeping in the back of my truck for longer visits.

Can you tell us a bit about your experiences growing up and how they shaped the work you make today?

My mom was a strong, independent woman, who raised me on very little. Raising me in a small apartment in Miami on a very small income, mom always found a way to get us by. I feel like I have her tenacity, a lot of her fearlessness, her drive.

My dad made photographs of the south Florida landscape, and printed them in the darkroom – I have memories of standing at the edge of the sink, watching. I remember the magic of the images appearing in chemistry. I think this stuck with me.

Are there unique qualities to West Virginian photographers?

There is a state pride, a love of home. It runs deep, and is evident in the work. All of the photographers featured here have figured out a way to make their work a major part of their everyday lives. They are all image makers whose work I deeply love. They are all self motivated. Some are in cities, some in more rural areas.

It has been inspiring for me to consider each one of these photographers, all of them at different stages in their lives and their careers, out there hunting the image, doing their processes, making this work because they have to. There is a real strength exhibited here. I would like to thank you all for creating the work you create, for giving the world your eye. Your work is important.

How did you find the photographers you are featuring?

I found these photographers in a number of different ways – some I knew already, and some I only knew of. Working on this has given me the opportunity to meet some photographers I didn’t know. I wanted to show an array of photographers representing different parts of the state, and a variety of photographers using different mediums, different processes, and at different stages of their careers. Mark Crabtree has been making work in West Virginia for at least forty years, and processes and prints all of his own work in the darkroom in his basement, Elaine McMillion Sheldon came from a journalism background and does documentary work, her stills giving us a personal pause with the people and places of this work, John Ryan Brubaker makes environmental work using a historic photographic process and acid mine drainage in his photographic development, Nic Persinger gives us a personal take on his view of home, and Meg Elizabeth Ward gives us dark, ethereal black and white poetry of her loved ones and the landscape she traverses.

Have you always worked with large format film? And when did you begin using the tin type process?

I started working with large format photography in college. During my senior year, I learned historic photographic printing processes, and I started photographing with an 8×10 camera. The 8×10 camera fit the work I wanted to do – slow moving, deliberate. I wanted to dive deeper – I wanted to learn how to make images from scratch. I received the Tierney Fellowship to learn wet plate collodion photography, to make collodion on glass negatives, when I graduated from the School of Visual Arts. I outfitted my then-vehicle, my little white Toyota Tercel, with a darkroom in the trunk, and went on my way to set out making collodion images on glass. I wanted to put myself out in the American landscape, and follow in the shoes of a USGS photographer of the late 1800s, but as a young woman traveling alone in a beat up car in 2007. It sounds very romantic, and it was. I made a lot of mistakes, and I grew up a lot on that road.

I didn’t start using tintype as a medium until I started photographing old time musicians. It seemed appropriate – it referenced the American-ness of the music, the historic nature of it. The tintype was the process that made photography affordable to working classes, democratizing photography, and that felt relevant, too – old time music is a music that is shared.

What draws you to photograph musicians?

I love old time music. My photographs are an homage to the musicians I photograph who are carrying on traditional music.

And oh man, it’s fun. I’ve visited with all of these old time musicians of varying ages, I get to see where they live. I learn about musical influences from different regions, and I get to hear so many good stories. I’m usually photographing someone with an instrument, so sometimes, I get to hear music while I’m working. Sometimes I get to sit down and play a few. When you do this kind of photography, you really have to spend some time with each person. That is part of the process of making this work.

Your book, Everglades, is one of my favorites. How did it come about.

Oh boy, thank you! That means a lot to me.

I had been working on that project for 8 years. Andrew Fedynak called me up one evening, to tell me that he was starting his own publishing company, Zatara Press, and that he really wanted to publish my Everglades work. I was a little dumbfounded. “Really? My melancholy landscape photographs?” Yes, that was the work he wanted to publish.

The book was a great collaboration. I had a say in the sequence, in the layout, and, most importantly, in the printing. My friend Sarah Brown of Questionable Press hand-carved a wood block of one of my photographs for the cover. Anne McCrary Sullivan wrote prose, and I included a journal entry. The book is 10” square, the size of the rear element of my camera. All of the text lives in a booklet that sits in a pocket on the left side of the book. The images live on the right side, the printing press we worked with matched my gelatin silver prints as closely as they could, which was pretty darn close. Watching stacks and stacks of the pages of my book printed on a machine that is bigger than any house I’ve ever lived in was pretty mind blowing. I’m proud of that book we made.

What’s next?

I’ve been working on a project for the past three years that I’ve kept pretty under wraps. I just exhibited it for the first time at The White Room Gallery in Thomas, West Virginia. It’s been my visual journal for the past three years. Using my 8×10 camera, I have been photographing the land, growth and decay, close friends, people I meet. I work instinctively. I will continue to work on this project.

I have been working fully analog. My neighbors have been so generous to me, and let me build a darkroom at their farm this January, which has given me a place to work a mile away from home. The photographs are shot on film, and printed on silver gelatin paper. There is no cell phone reception, no internet access in my darkroom. It allows me to be present with the work.

I have been teaching workshops on the road, visiting schools, and teaching at the Penumbra Foundation. I just worked on a piece in the October issue of Harper’s Magazine, for the article All Over This Land: Local Politics in the age of Trump. I am actively seeking more editorial work.

And finally, describe your perfect day.

Waking up to the sound of the birds, the sunlight streaming through my window. A long walk in the woods. Photographs made. Time in the darkroom. Silly jokes, bad puns, a long hug, some good conversation. A meal made and shared with loved ones. Being present, others being present. No iPhones, no digital technology. A good swim. Ice cream. Music.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Patricia Howard: Unknown AncestorsFebruary 5th, 2026