Maxine Payne: The States Project: Arkansas

For Day Three, I’m introducing the work of Maxine Payne. I first met Maxine when she had a show of her photographs at the Baum Gallery on the campus of University of Central Arkansas (UCA). Little did I know a few years later that Maxine would be leaving her teaching position at UCA to teach at Hendrix College in town. She asked if I would be interested being Visiting Assistant Professor for a year and that was sixteen years ago.

Maxine is very driven and that’s one qualities that I admire about her. I have chosen her ongoing series Cull of the Litter because I think we can all relate to this, myself included. Also, I have included her project Making Pictures: Three for a dime, where Maxine has worked with the Massengill family to shed light these photographs of the 1940’s that had been lost. These photographs show us an intimate portrayal of people and families of the rural South.

Maxine Payne is a photographic artist living and working in the foothills of the Arkansas Ozarks, where she was raised by her grandparents. Exploring life within communities both familiar and strange, she documents the richness of vernacular cultures in all their peculiar glory.

“My work is a way for me to understand where I come from, a way to honor it, to be critical of it. I have always been searching for this idea of home and belonging. I think the more experiences I have in the world, the more motivated I am to identify with a sense of place. It is what makes me who I am.”

Maxine makes pictures of the people whose lives have crossed and shaped her own, including the rural Southern women who brought her up. Using a variety of antiquated camera techniques and darkroom processes, Maxine creates dreamlike images evoking the same aura of mystique, which surrounded early photography. Ever on the lookout for a good story, she often incorporates her subject’s oral histories into her work, ultimately weaving a sprawling, ongoing, abstract documentary of rural like, which continues to illuminate and affirm the inimitable spirit of everyday people.

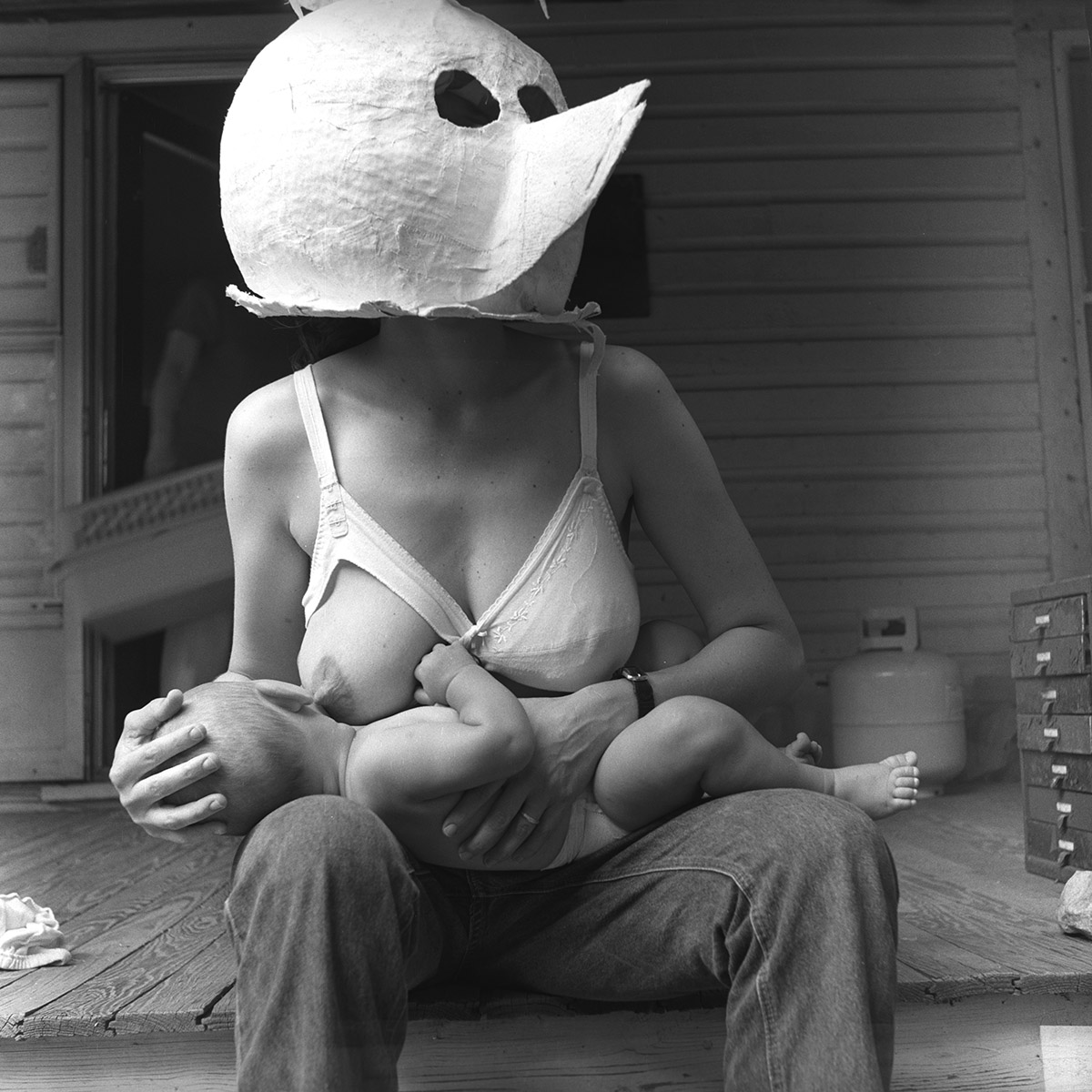

Cull of the Litter

Much of the motivation I have to make art is driven by my desire to be part of a community, to have a sense of place. I kept silent about my Arkansas upbringing when I went off to get an education. The art world separated me from what I identified with culturally and challenged all the beliefs I had been raised with. Feeling out of place at home is a terribly disconcerting condition and this series was my reaction to that. Perhaps too, it was my attempt to empathize with the underdog or outsider, something I have done all my life.

This works has continued as my life has changed and I have gotten older. Much of the angst I was experiencing has tempered with age, and especially with the birth and rearing of my daughter. However, anyone who grows and changes and accepts new challenges in life must have some insecurities that continue to haunt them. That is what this body of work is for me. – Maxine Payne

Making Pictures: Three for a Dime

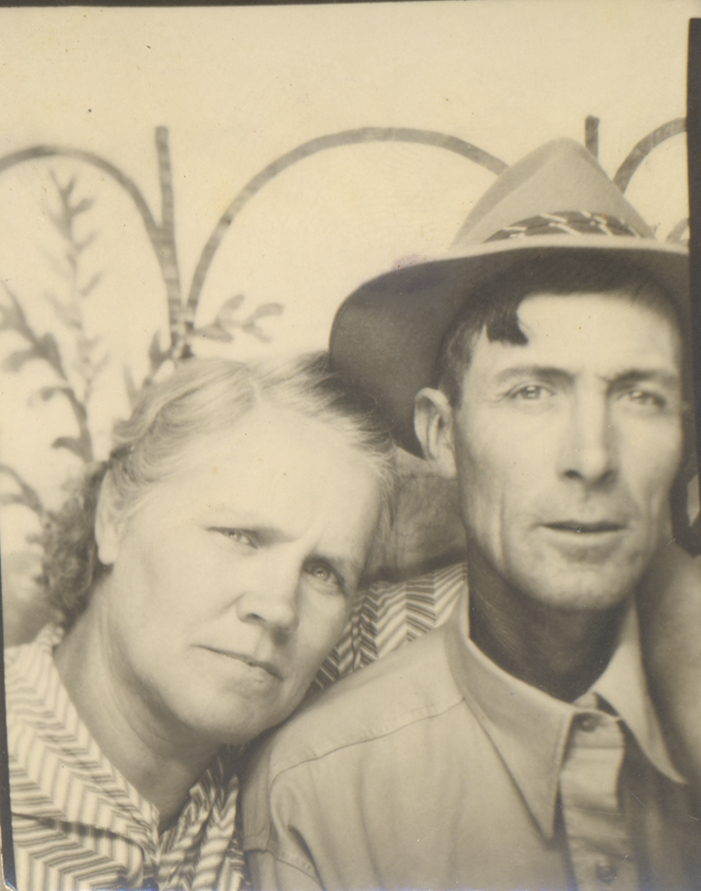

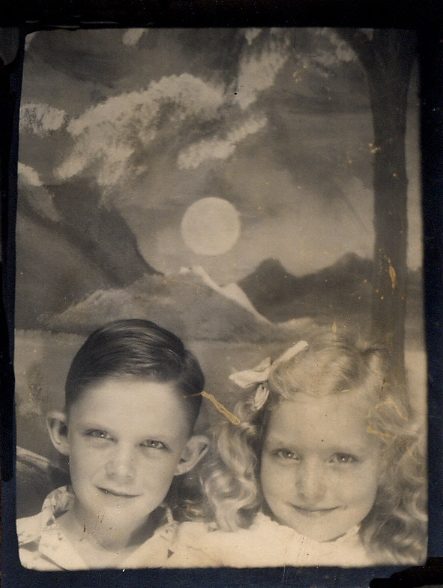

One Saturday morning in the mid-1930s, Mancy Massengill, a wife and mother of two, saw people having their pictures made in a dime store photo booth in Batesville, Arkansas. According to her son Lance, “she watched close, and got the name off the camera, then wrote to the company and ordered the lens. She got the money for that by taking about two‐dozen pullets in for sale.” Her husband, Jim, built a box to house the lens and outfitted a trailer to create a mobile photo studio. On weekends, they would set up in little towns across the state and make pictures, three for a dime.

Jim and Mancy Massengill started this family side-business to make ends meet. The country was in the throes of depression and on the verge of entering the Second World War. Work was scarce in rural Arkansas, but the Massengills understood that even in rough times, life continues. Babies are born, children play, couples meet, and we all grow older. Someone needed to be there to capture those moments and that person could perhaps make a living doing it.

A few years later, the Massengill’s sons, Lance and Lawrence, and their wives, Evelyn and Thelma, worked their way into the business. They outfitted their own trailers and made their own pictures, traveling across the state in search of clients. The surviving family diaries and notes from this period attest to a very strong and entrepreneurial work ethic, with little mention of aesthetics or technique. The men and women of both generations describe where they went, what they did, and how much they made with only fleeting mention of life’s details. With few exceptions, the stories are left to be told by the pictures they made.

The Massengill family photographs can be playful, serious, strange, and at times, haunting. Originally created as precious souvenirs, these photographs recorded moments experienced by the very young, the very old, and everyone in between. Viewed today, the images provide us with honest and intimate portraits of life in the rural South in a bygone era. The photographs collected in this book were all created by members of the Massengill’s extended family in the 1930s and 40s, but the individual photographers remain, for the most part, unknown.

It is the stuff of literature, film, art, and music – life turns on a dime. Mancy Massengill walks into a store and has the idea to start making photographs. Almost seventy years later, Maxine Payne, a photographer from Arkansas, reconnects with a family friend, Sondra Massengill, the daughter of Lance and Evelyn, and is invited to discover hundreds of photographs that she never knew existed. Those two events, not excluding everything that happened in between, have brought this project into being. Today, thanks to luck or providence, or both, we have been afforded the opportunity to see these photographs that would have otherwise been lost to the slow but inevitable passage of time. -Phillip March Jones

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Joli Livaudais: The States Project: ArkansasFebruary 24th, 2018

-

Kristen Spickard: The States Project: ArkansasFebruary 23rd, 2018

-

Maxine Payne: The States Project: ArkansasFebruary 22nd, 2018

-

Carey W. Roberson: The States Project: ArkansasFebruary 21st, 2018

-

Gary Cawood: The States Project: ArkansasFebruary 20th, 2018