Nathaniel Grann: Midwest Sentimental

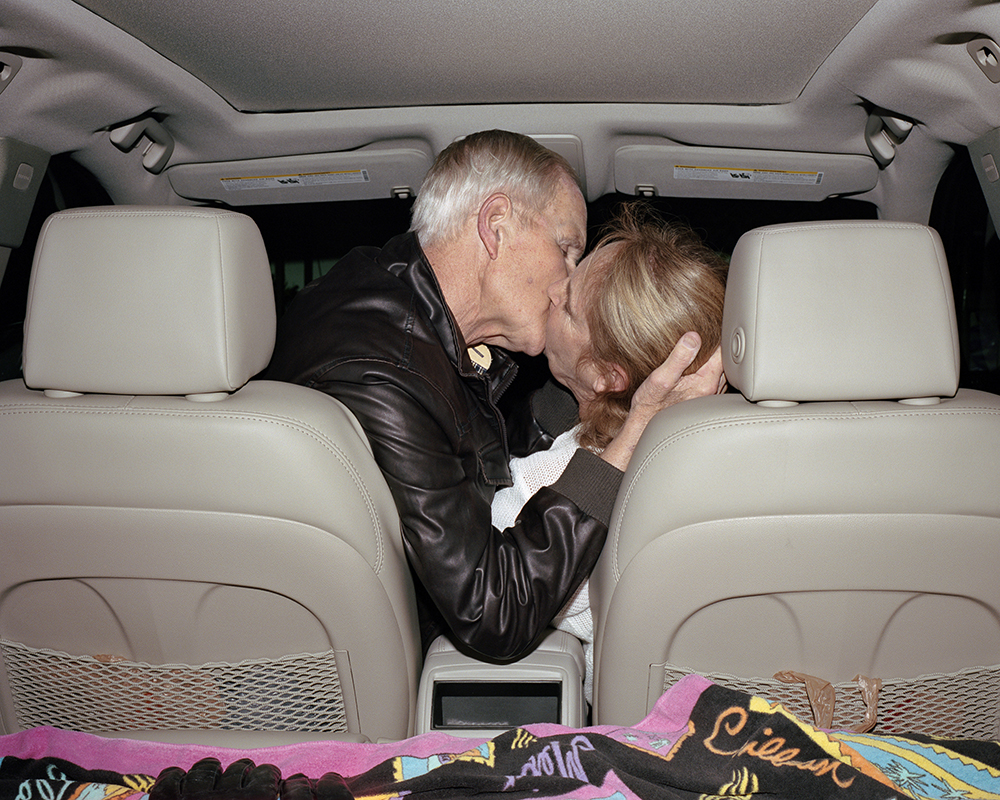

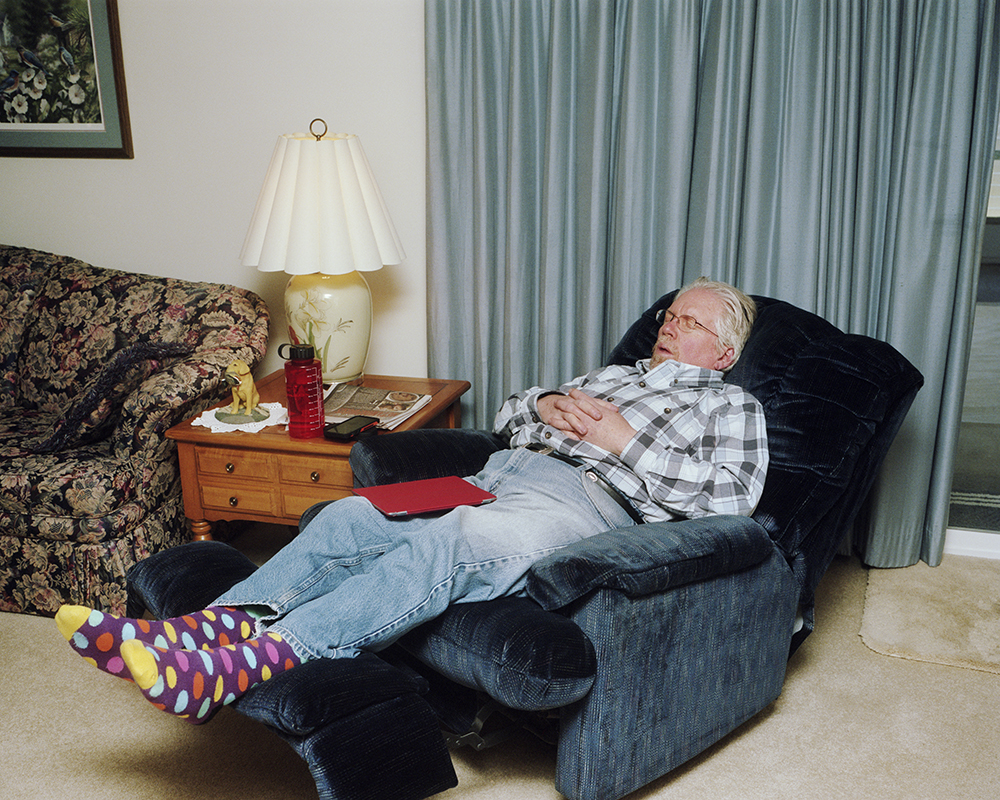

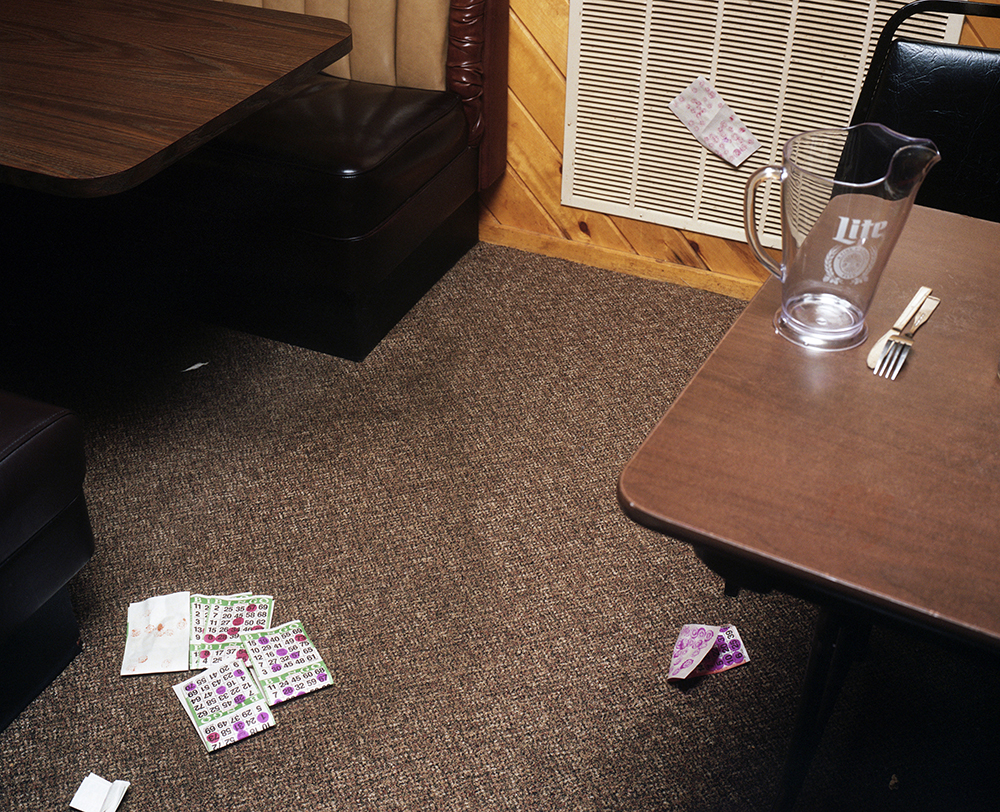

In Midwest Sentimental, Nathaniel Grann invites us into the intimate world of his Minnesotan family. As with most portraits, we learn more about the photographer himself than the family members he portrays. Grann employs multiple styles of imagery throughout the series: family snapshots that would fit perfectly into a plastic-coated album, atmospheric images of a cold, wintry landscape, and flash-lit interiors of his family’s taxidermy-filled homes. The pictures have the feeling of an outsider looking in, despite Grann’s midwest upbringing. Having left home for college at 18 certainly has to do with this. Grann returned at age 24 to make this work, reevaluating the notion of home and looking at this place with a different visual understanding of the world around him.

Nathaniel Grann is a photographer and photo editor from Minnesota currently living in Los Angeles. He received his MFA in Photography from the University of Hartford in 2016, and his undergraduate degree from the Corcoran College of Art & Design. He currently works as an editorial picture editor at Shutterstock and has previously worked at The Washington Post. He recently released his first monograph, Midwest Sentimental, with Peperoni Books which is available for online purchase here. You can also pick up a copy at the New York Art Book Fair September 21-23 at the Hartford Photo MFA table.

I spent three years of my mid-twenties living in my mother’s basement in the American Midwest. Love, sadness, and humor have come to define those years, which led me to ask:

What makes a family click?

What holds a family together?

And, what allows for a family to move on from a troubled past?

In three years, I found few definitive answers. Instead, what came of it was the experience of a collective exhale of momentary release and reflection. – Nathaniel Grann

VW: How did you arrive at the title Midwest Sentimental?

NG: The title of the book is a little tongue-in-cheek, but rooted in how I would describe myself in relation to the midwest—a midwest sentimentalist. Sentimentalism is a word often thrown around with a negative connotation in art, particularly in work that some may find kitschy or overbearing. I would suggest, though, that what most people find too sentimental is actually romanticism. This mix of nostalgia and romanticism leads to some well-trodden visual cliches often attributed to the American Midwest (i.e. cornfields, old cars, sunsets on the prairie, etc.) that I’d often find myself reacting to and often taking photos of. For this project, I didn’t want to contribute to this idealized, romanticized notion of the region, and attempted to instead express notions of sentimentalism as an extension of my desire to further explore myself and the idea of Family.

VW: Who are the characters that we see repeatedly throughout this work?

NG: My mother, father, stepmother, and stepfather make up the majority of the recurring characters in this work, with a lovely cameo from my niece a few times, too. Luckily most of my family was receptive to being photographed, but it was important to me to respect their boundaries and give them the right to opt out of any pictures they weren’t comfortable with. While I know a few of them probably feel that the whole ordeal was pretty silly, they’re all proud of the book and to have taken part in the creation of the work. I was as transparent as I could be when pitching a new idea for a photograph with them. Some of the photographs were even dreamt up collaboratively, based on shared memories of past events in our family’s history. In the end, these images shouldn’t be considered literal documentations or an exact reflection of my father or mother; instead, they should be viewed as a reflection of myself as I play the role of a memorist.

VW: Can you walk me through a day of shooting this project?

NG: A typical day was usually focused around conversations I would have with my family members. We would talk about shared memories, or I’d show the photographs I had been taking and things that had been inspiring me. We’d talk about what we saw in those photographs and what they reminded us of. From there, I would make a shot list of new ideas for us to cover in the coming weeks. reflecting on what we had discussed. In the end, there were a lot of images left behind or ideas that never came together, which ultimately opened up paths to new ideas.

VW: What were your primary influences when making this work?

NG: Along with the ongoing conversations I was having with my family members, I also pulled from my own family snapshots. At one point, I started to see my niece ‘performing’ as I did for the camera around her age. It was strange to see this cycle continue and how similar her poses were to my own. As the youngest child, I’d try out new ‘smiles’ or new ‘joke’ poses for the designated family photographer. To see these similarities was a bit of a eureka moment for me, and made me start to think of these snapshots as being on equal footing with the more staged and planned out photographs.

Photographically, artists Larry Sultan and Doug DuBois paved the way for a project like this. In my mind, they have created some of the most heartfelt bodies of work around the idea of Family and continue to be examples of the caliber and quality of work to which I aspire. The late swedish photographer Lars Tunbjörk was another influence for me. His photographs often ride a subtle line between humor and sadness that is both relatable and endearing. Mary Frey is another photographer who has done so much in the genre of family, helping me root my own understanding of what it means for a photograph to be ‘true.’ Her photobook Reading Raymond Carver is one I continually recommend and has been a favorite for some time, and I cannot wait to get my hands on her new book, Real Life Dramas.

VW: You include a single self-portrait in this project. To what extent do you see yourself in these pictures?

NG: I like to think I’m present in every photograph, which goes back to that attempt to characterize my family members as archetypes of family personas—even when I’m not literally present in an image, it’s very much rooted in my own personal point-of-view. I also took on one of the recurring characters in the book, the Family Photographer. We started to consider this character while brainstorming image ideas and would work in ways for the character to further materialize.The character isn’t the easiest to notice at first, but with the consistent use of direct camera flash, the character becomes present in the high-key marks caught in reflective surfaces.

VW: Has your perception of this work changed since making it during your MFA in 2015-16?

NG: Yes, definitely. I wasn’t quite in tune with what I was channeling while making the work, and can now see that much more clearly. A lot has changed in my own life and my families’ lives since I’ve finishing the project. This has allowed for more clarity when reflecting on that time in my life.

VW: We lost the great Hannes Wanderer of Peperoni Books last week. You worked with him closely to make Midwest Sentimental. Could you share a memory of your time spent with Hannes?

NG: Hannes was an amazing guy. His passion and love for all things photography, art, and music was unmatched by anyone I’ve ever met. The book wouldn’t have happened without him and I will be forever grateful for the four years of friendship we had. One of my favorite memories with Hannes was from the last time I saw him, this past spring. I was in Berlin to print Midwest Sentimental and had just arrived after a marathon of flights. I met up with him at his shop, 25books when he remembered he needed a portrait for a lecture series he was proposing about Bob Dylan. Somehow our shoot ended with us clearing out a corner of his store, grabbing a framed photo of a guitar, and Hannes posing as if he was playing said guitar. It was all a bit surreal, but I learned more than I’d ever expected to about Bob Dylan that afternoon and still can’t hear ‘Blowin in the Wind’ without thinking back to that day.

VW: The construction of Midwest Sentimental is so well thought out. I particularly love the artificial wood-like cover. Running your fingers over it feels like touching hardwood laminate, referencing a certain quality of midwest kitsch. Can you tell us more about the design considerations you made for this book?

NG: I was thrilled with the cover material Hannes was able to find for the book; it looks almost identical to a wood paneling my grandfather had across his entire screened-in patio. The tipped-in front image of the Hooded Merganser pair is another reference to that space: my grandpa would always hang his bird mounts up on the wall with an attention to detail that never quite squared up with the rest of the room’s ambience.

For the inside of the book, we wanted to keep the design clean and simple. It was important to me to give all of the images a democratic treatment on the page. I didn’t want to imply any form of hierarchy between the different approaches to image making. That placed importance on the sequence of the images, which definitely took up the most time. I am really happy with what we landed on. The book is made up of five small vignettes — pairings of three to five images that, when viewed in sequence, imply some form of narrative.

Each vignette integrates my varying methods of photographic approach to create a sense of narrative. Over time, this builds my family and the individuals that make it up into characters. In doing this, I hope that viewers find some sense of familiarity and reflection on their own ideas on the notion of Family. Family is complicated and full of nuances that are very particular to us as individuals, but ultimately, there are universal strings that run through all of our collective experiences.

VW: How does this work speak to the Midwestern identity, and where do you fit into that?

NG: The American Midwest is a huge area and much more diverse than people realize, so it’s hard to think of it in terms of a specific photographic identity or tradition, like the ones that have come to be associated with the American South and Southwest. It’s difficult to think of the Midwest as having a singular identity, let alone how that would translate to a photograph. I go back and forth on whether this series really is about the Midwest or not. While I know that I’m very much a product of my place and home, I think I’m still trying to sort out how that is reflected in my work.

VW: You now live in the abruptly different environment of Los Angeles. What’s next for you there?

NG: Los Angeles is definitely not Minnesota! It’s taken a while to get used to, but there is something to be said about perpetual summer. I think I’m still trying to find my groove out here, but I have been trying to live more in the moment with my work, letting my curiosity lead me to what I photograph. I co-founded the Image Threads Collective with fellow photographer and dear friend, Jenia Fridlyand. The photography-focused teaching collective has recently held events in Havana, Kiev, and New York, which I’m really excited about. I have loved working with our students on expanding their projects and interests in photobooks. Next week I’m flying to New York for the New York Art Book Fair at PS1, where I’ll be selling copies of Midwest Sentimental amongst photobooks by other Hartford alumni. I hope to see some of you there!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026