Dutch Week: Eline Benjaminsen

To close this Dutch week, I’m introducing Eline Benjaminsen who was in fact born in Norway… I’m pretty sure it’s not cheating though, as Eline moved to the Netherlands when she was 19 to attend the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, where she was taught by only Dutch teachers. She has spent the past 7 years living, studying and working in Holland. Her work “Where the money is made” has earned her the Steenbergen Stipendium in 2017, which is a prize given to a photography student for the best graduating project of all Dutch art schools combined. Benjaminsen also received Second Place in the story-telling category of the renowned photojournalism awards Zilveren Camera. She’s one of many very young photographers who illustrate how Dutch photography continues to have a bright, interesting and strong future ahead of itself.

Her publication under the same title can be purchased on Benjaminsen’s website.

Excerpt of video essay from “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Sound composer: Yon Eta.

Eline Benjaminsen (Norway, 1992) is a video artist and photographer who’s work explores the visuality of socio-economic processes. By focusing on the strictly physical – that which can be photographed, her work offers a social realist approach in dealing with the relation between the material and the immaterial.

Her projects have appeared in a variety of platforms including Nederlandse Fotomuseum, Stroom Den Haag, Heden Gallery, the Dutch Financial Daily, Krakow Photomonth and Migrant Journal. She graduated from The Royal Academy of Art in The Hague in July 2017 with the project ‘Where the money is made’ on the infrastructures of algorithmic trading. The project earned her the Steenbergen Stipendium and the second price in the Zilveren Camera category “Prijs voor Storytelling”.

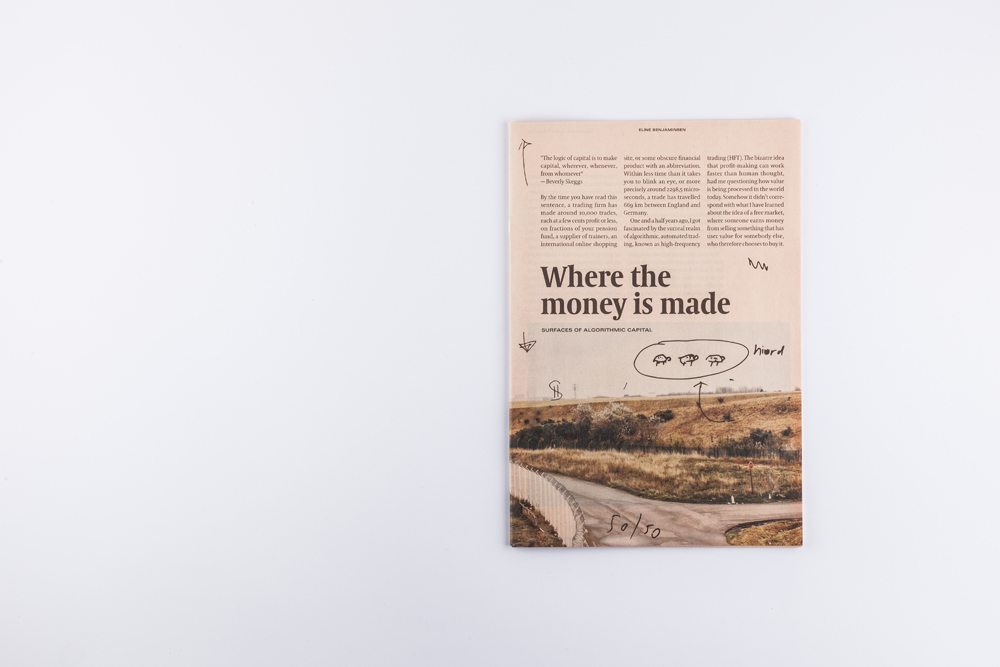

Where the money is made – Surfaces of algorithmic capital

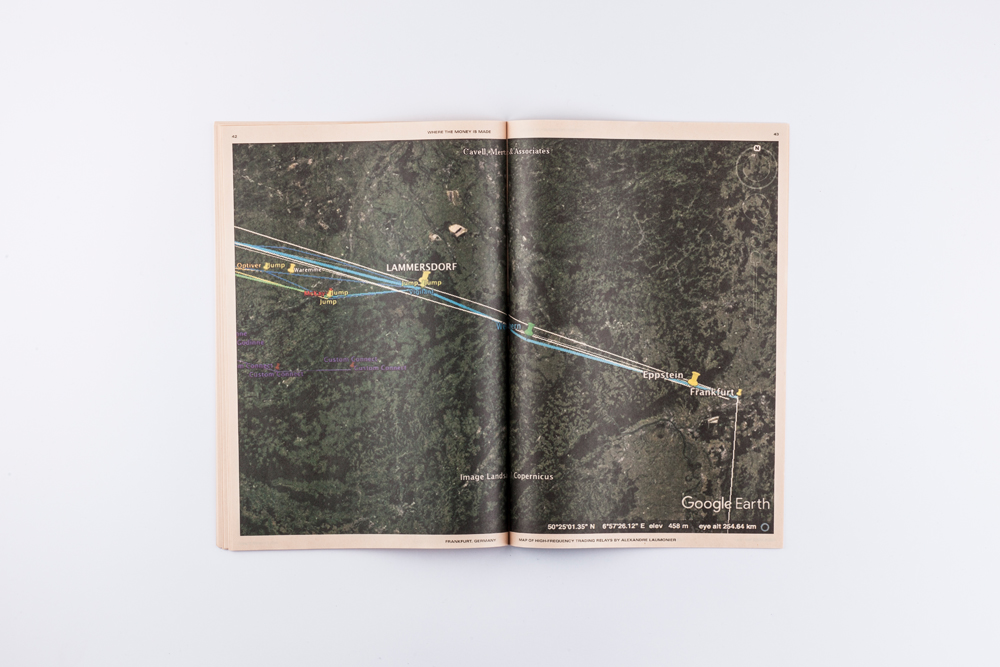

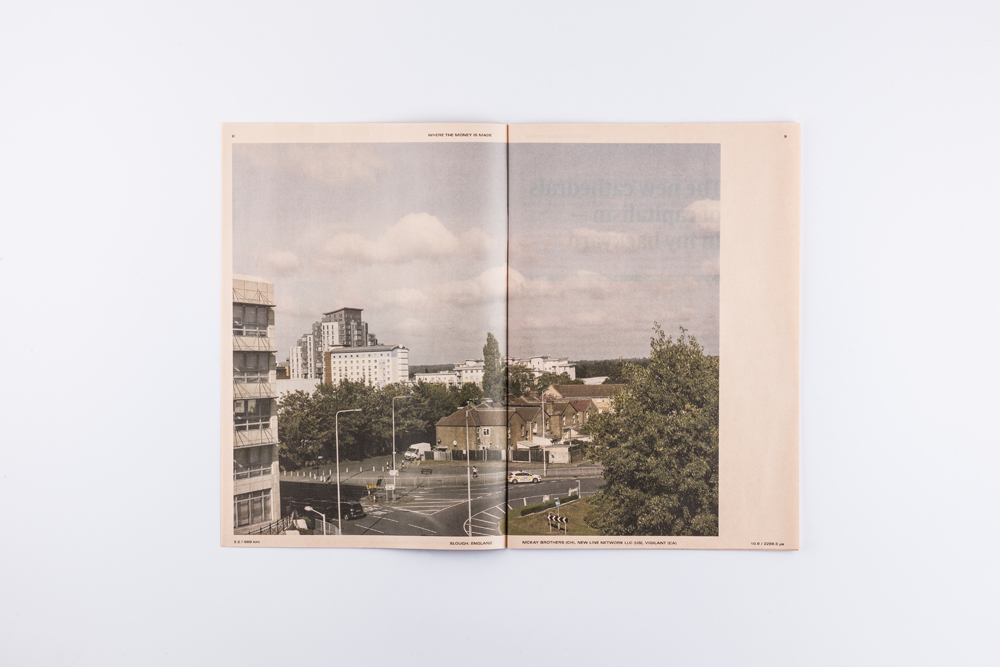

By the time you have read this sentence, a trading firm will have made approximately 10,000 trades on the stock market. Welcome to the bizarre world of algorithmic, automated trading known as high-frequency trading. Here, profits are made at speeds the human brain can’t comprehend. Where the money is made aims to bring this obscure economic power to light by tracing lines of algorithmic capital to the places where some of the greatest profits are made today. Guided by the geometric lines-of-sight between microwave transmitters and receivers, the work documents the mundane everyday landscapes of globalized financial infrastructures.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

This body of work is your Bachelor project for the Royal Academy of Art in the The Hague. You’ve chosen a rather unusual topic as photographic subject matters go, and the way you chose to photograph it is also rather “different” – I mean, you didn’t photograph traders on the floor for instance. Why did you choose to make work about this, and why this way?

When I first heard about high-frequency trading, which is the strange thing that I’m dealing with in this work, I got very fascinated by how high-finance meeting artificial intelligence works to the point where buy and sell orders are going faster than humans can process thought. This made me question how value is being processed in the world today. But then, there is also this other huge question here: basically, how can we start to comprehend those complexities when they are that great? And so my purpose, or my goal, what I hope to be doing in this project, is to look for ways to make images that can serve as a point of departure in the process of starting to comprehend this matter. I find this important, simply because how can we know if we want an economy that functions the way it does if we don’t understand it – right?

You say it’s an unusual topic, I don’t find it so unusual. First of all, what these images are showing is in fact the “traders on the floor” of today. Since most of the pits of the exchange are no longer active, these silent lines of code that I intend to photograph are doing the bidding the traders used to do – but then far faster. For me as a photographer, when the visuality of something is completely gone, that leaves me with a very interesting challenge. How is the new image of stock-exchange, and why does it matter that it doesn’t take any concrete, physical shape today?

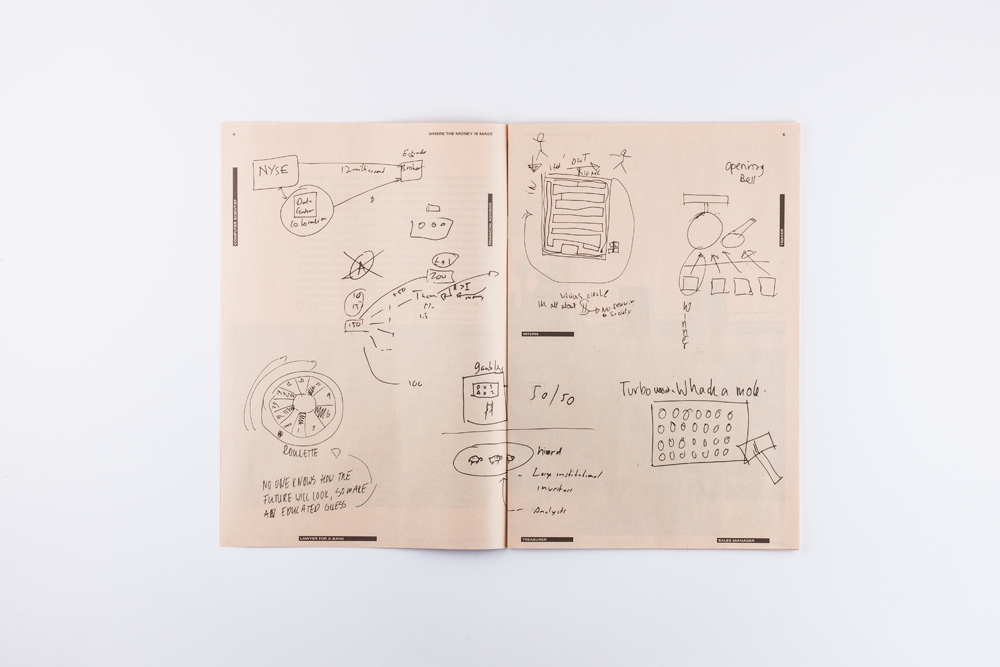

There are people behind the algorithms of course, and people monitoring them and deciding how they act. There are quite a few trading companies in Amsterdam that do high-frequency trading. However, I wasn’t allowed to photograph these places, but maybe I will be able to in the future, who knows. I was photographing these landscapes of where the high-frequency trading takes place, but there are people in this story, and I felt that I was missing their perspective. And so in the publication, there are drawings from people that I approached in the streets of the financial district of Amsterdam. I asked them to draw for me in the simplest possible way an explanation of how high-frequency trading works. Many said “It’s not illegal, you know, there’s not really profit here for society as a whole, but it’s not illegal.”.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

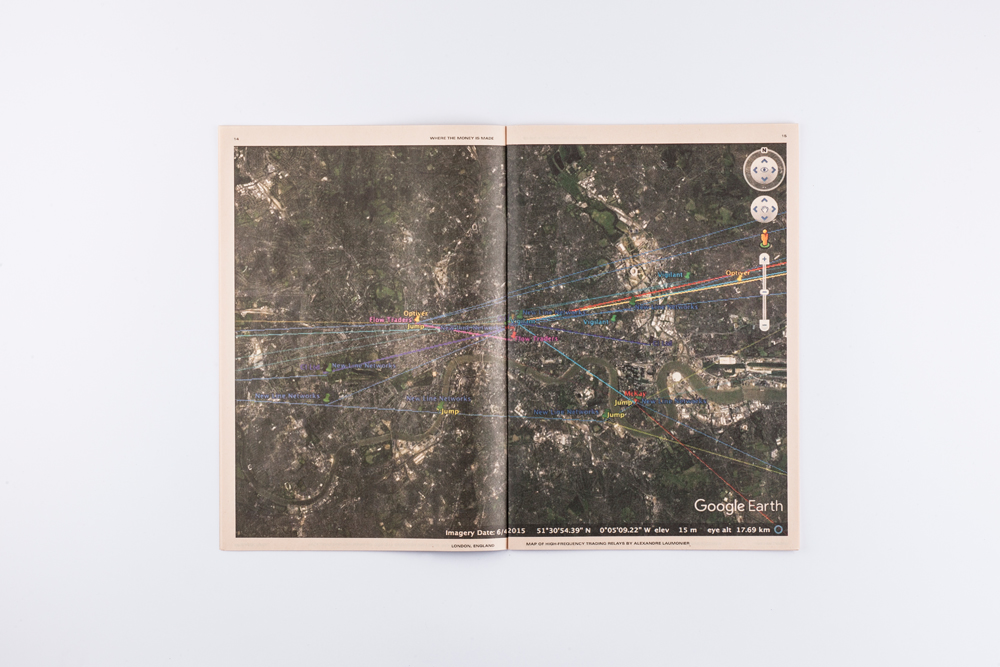

But what got you started?

Actually I started to get really fascinated with this topic when I found this map online by a French writer / researcher / publicist / designer, Alexandre Laumonier. He archives, through mapping, the routes of microwave relays that the trading firms use to send their order-data between exchanges. And then he open-sources all his findings on his blog (https://sniperinmahwah.wordpress.com/). His map allowed me to go to the places that I’m photographing in this project, which are the physical places of this immaterial market place. These places are ultimately where some of the biggest profits are being made today.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

I find the layering in your project is quite mind bending. The fact that you’re photographing a physical place thinking of this alternate intangible dimension, it’s hard to wrap your mind around it. Often photographs of place teach us something about the people who built it, or the people who live there. What do the places that you photograph tell us?

Very little and that’s the whole point. In the perspective of high-frequency trading, they don’t actually tell us anything at all. They’re just random very mundane boring places. But most importantly they are not places that you would associate with high-finance. And it also talks about how this market place, and profit, is happening there. You could go further in the interpretation and say that this flow of capital is obviously not landing in these places where it is passing, so there’s also this kind of contrast.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

You won the Steenbergen Stipendium last year (huge congratulations for that!). That’s how I came across photographs of your graduation exhibit. Can you tell us more about the installation part of the project, which is definitely more than just photographs?

First off, I’m still working on this project now, and the installation part is hardly the same anywhere. I first made the photographs, then the video. The publication kinda came together gradually. I wanted the publication to be cheap and accessible, those were my two goals. Furthermore I put a lot of emphasis was on making smaller fragments that can be seen both together in one installation, but also independently from each other. For me this project has a lot to do with a general understanding of something, so to use different stages, it makes sense, because the film can travel where the publication can’t and vice versa. You can say that the publication is more of a hard-thinking part, it contains essays by people that I’ve been working with, and it contains more data – it invites you to take a dive into the topic. And the film is much more like a philosophical take on this lack of visuality. Here I don’t even mention high-frequency trading, it’s very stripped off of technicalities.

This year I’ve been able to really experiment with the spacial part of the project because there’s the film, the publication and then there are the prints, and a few other more interactive elements too. What I really enjoy about this project is that I have this sort of material archive, material bank, and I can mix and match to fit the different platforms I’m dealing with. What you see online is my graduation installation, where I had all elements on view. But I just recently had two exhibitions in the Hague, one at Heden, which is a gallery, where I had prints mainly, and then one at Stroom, which is an art center, where I had the video in a more cinema-set up. With the gallery, it was really interesting to sort of commodify this project I guess – how you make commodities out of those images that question value in its essence… I enjoy the experimentation with different platforms a lot, thinking about how a gallery is different than an art center and a newspaper and a museum. How the spaces themselves reflect the topic.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

So you worked with Alexandre Laumonier, Sophie Dyer and Joost Dobber on the publication – was it a collaboration from the start? How did it come about?

This project came about through a lot of collaboration which grew organically. I contacted Alexandre to ask him questions about the maps. Since then, he has been helping me a great deal. I guess we have sort of been open sourcing our works to each other, he generously shares his knowledge and maps and research with me, and he uses my videos and photographs. Sophie Dyer, from London, is a design researcher. Her essay in the publication is an analysis of how during the summer of 2016, these two flows, of migrants in the refugee camp called the Jungle in Calais, and the relays of high-frequency trading, passed each other. We met up in Calais and were following those lines of capital, between the microwave transmitters, one of them going straight through the old refugee camp. We recently also worked together on a publication for oneacre.online: (www.oneacre.online). There’s also Joost Dobber who is a financial journalist for the Financieele Dagblad. We collaborated on this story of Richborough, a small place in Kent near Dover. The inhabitants there got proposals from two trading firms that wanted to build towers, as tall as the Eiffel tower, to get their microwave links across the Channel. And the inhabitants ended up protesting, they found the blog of

Alexandre and decided this was not what they wanted in their backyard. So these three, they all wrote essays or articles, that all talk in their way about how high-frequency trading intervenes with our physical world, and I generously was allowed to include them in the publication.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

You were born in Norway but you moved to the Netherlands at 19, so about 7 years ago, and you were a student at reputable Dutch art school, where all your teachers were Dutch etc – do you feel this Dutch “immersion” has influenced the way you shoot? And if so, how and to what degree?

That’s a really interesting question. I never really sorted this out. So I have to think about it… Huh, let’s see. I think definitely the kind of traditions that are here within storytelling through imagery, especially within longer running documentary photography projects, I definitely learned from those. It’s a really difficult question to answer because how to know how I would have developed if I had been studying in Norway? I have no idea… Maybe there’s the absolute straightforwardness of the Dutch that I have learned. Wow, really going for the cliché here. I suppose the way that I go about this work is super rational. I go somewhere, there’s a line of microwaves in the sky, and that’s where I put the drone, or that’s where I take the picture. You know, it’s the most straight forward way to go about it. One thing I know for sure is that the time at the Royal Academy has been a really intense period; coming there as a teenager, you learn to find what you are really fascinated with, and then how you want to go about talking about those things in images, and why you want to do that. Which can be quite tough but mostly absolutely terrific.

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

So what’s next for you?

I’m working on expending the project. I left it for a year, and now I’m picking it up again, opening it up. And now it’s really great to re-examine it as something that is still in progress – it’s really refreshing. For example, it gives me the possibility to reconsider the things I decided to leave out during the time I was graduating. One thing that I want is to make the work more immersive, when it comes to the installation of it. I have different ideas for this, expanding the video work for instance. So I’m in The Hague, continuing this work, and I’m really enjoying it. I just did a residency at Dockingstation in Amsterdam and in Krakow, getting to meet a bunch of people such as curators, editors and other artists, and that has enabled me to test case this project and the installation of it, and I got a lot of input from that. I’m now developing it in the sense that I’m thinking of it as an installation that expands, with multiple smaller fragments that can be viewed independently from the whol

From the publication of “Where the money is made” by Eline Benjaminsen. Texts by Sophie Dyer, Alexandre Laumonier and Joost Dobber. Design by Titus Knegtel.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026