Sophie Calle: Detachment, Death, and Dialogue

” Private – a word from the past, or so it would seem these days. A word of hardly any relevance in an era when everything – from one’s favourite recipe to one’s current relationship status – is posted on Facebook. Exhibitionism, self-revelation, the urge to tell stories, the pleasure of presenting and voyeurism are the social strategies of our day and age. “

For the past forty years French multidisciplinary artist Sophie Calle has been gently asking us to question what constitutes art at its very core. Conceptual art is primarily known for the supremacy of the idea over its execution, yet Calle skilfully combines concept and presentation. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of Sophie Calle’s philosophy while specifically focusing on certain works, and examine the idea of expanded photography, i.e. photography combined with various other art forms. It will compare and contrast Calle with other practitioners and it will also look at ideas that Calle’s work, I would argue, draws inspiration from and comments on, like the use of the archive, Barthes’ notion of the death of the author, and the alchemy of combining imagery with language.

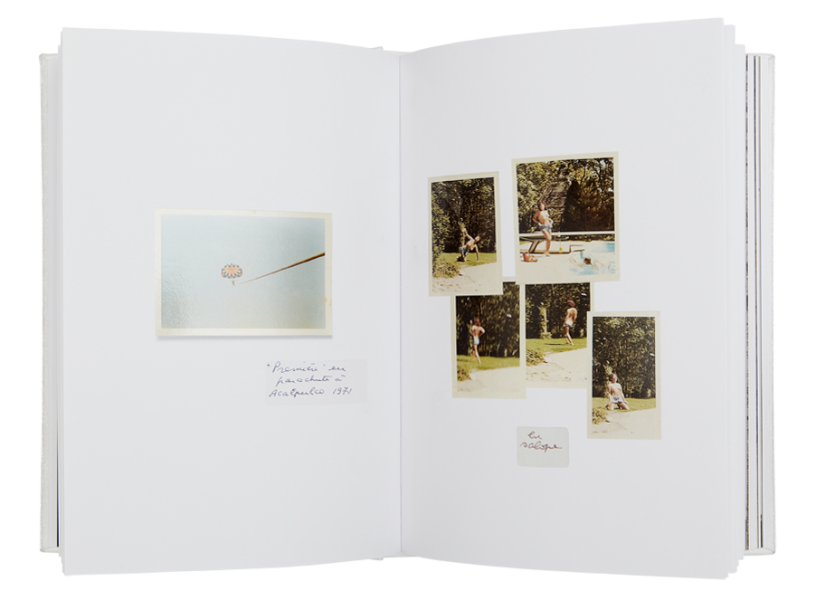

Looking at Rachel, Monique… (2012) and the photographs with the inscriptions made by Calle’s mother reminds me of my grandmother Trendafila’s archive of family photographs. They were old pictures dating back to the early 1970s – very small pieces of paper, some no bigger than 3x4cm. In the mid 70s, shortly after my father was born, the family moved to Komi in the USSR where granddad worked as a doctor and grandma was a nurse while the rest of their relatives stayed in Bulgaria. Since this was prior to the invention of Skype or even mobile phones, my nan was physically mailing photographs as her sole method of communication. It is difficult to imagine what this must have felt like – now we live in the age of instantaneity where everything is only one click of a button away. I live 2,000 miles away from my parents and we regularly FaceTime and send selfies. My grandmother could not do this because the technology was not there yet – she had to buy film for her camera, load it, take a picture, have the film processed, get the pictures printed and send some of them out to family while keeping others in the family album. Today most kids would not know this as for them, unless they are art students, a photograph is something they take with their phones. It is hardly considered due to the lack of monetary cost (apart from that of the device), and in the majority of the cases it is created in the phone, it lives there and, eventually, it dies there too when the user runs out of space. The birthplace of the image eventually becomes its graveyard in a cannibalistic fashion.

To go back to my nan’s pictures, what struck me most was that she had written messages on their backs, in a similar fashion to postcards. They were mundane, domestic images, nothing extraordinary. On one, for example, she had written “Look, mum, I’m eating well” – the image is of herself in the kitchen, licking a wooden spoon while cooking a stew. Presumably it was sent to my great grandma Hope who had, understandably, been worried about her twenty-year-old daughter with two small children. Grandma had employed photography as the instrument of indisputable truth. Pre-Photoshop photography did not lie, or at least that was the most prevalent belief, which we now know to be erroneous. According to John Berger, a photograph is a piece of evidence that the particular scene it depicts happened in reality. It shows nothing more than, in this instance, my grandma having been in front of the camera doing the activity that she was at the time. Everything else is open to interpretation – maybe she was trying to comfort a worried mother by constructing a scene, which, albeit true at the time, connotes a false reading. Or perhaps she really had been eating well and considered a photograph the most suitable evidence.

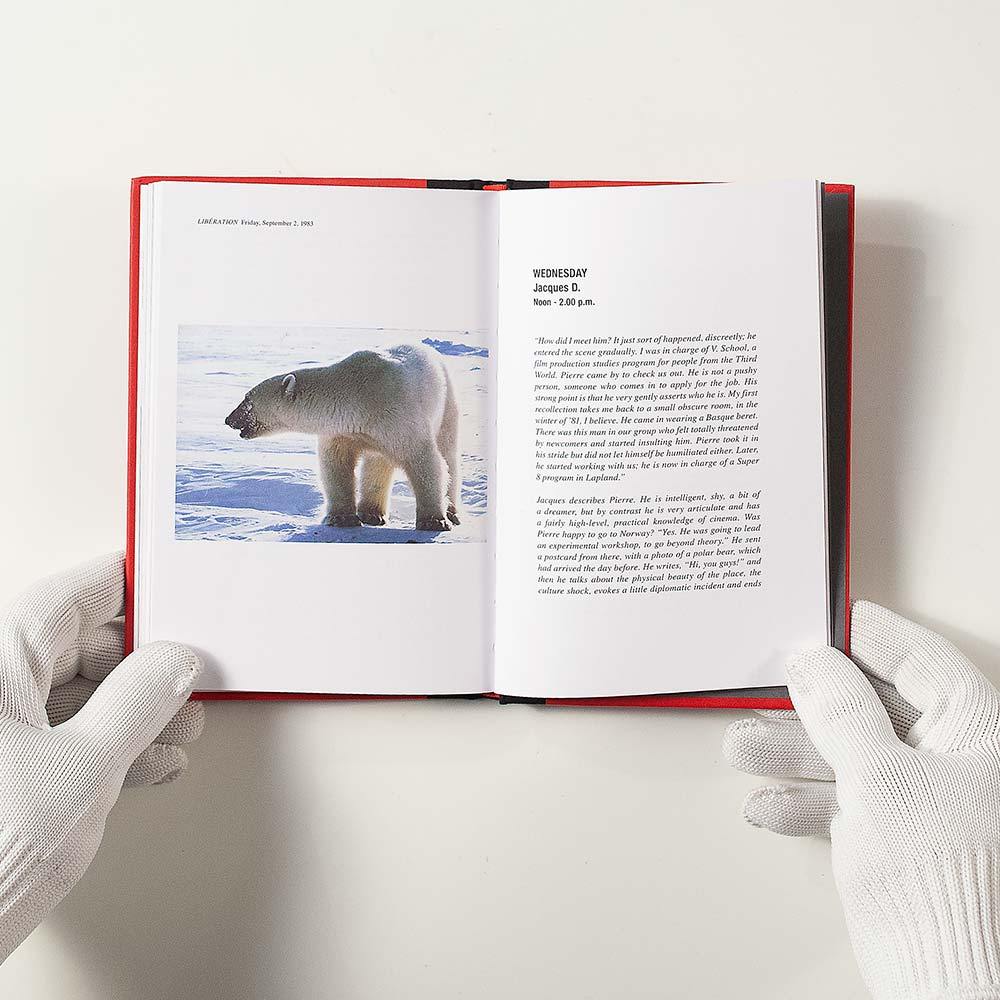

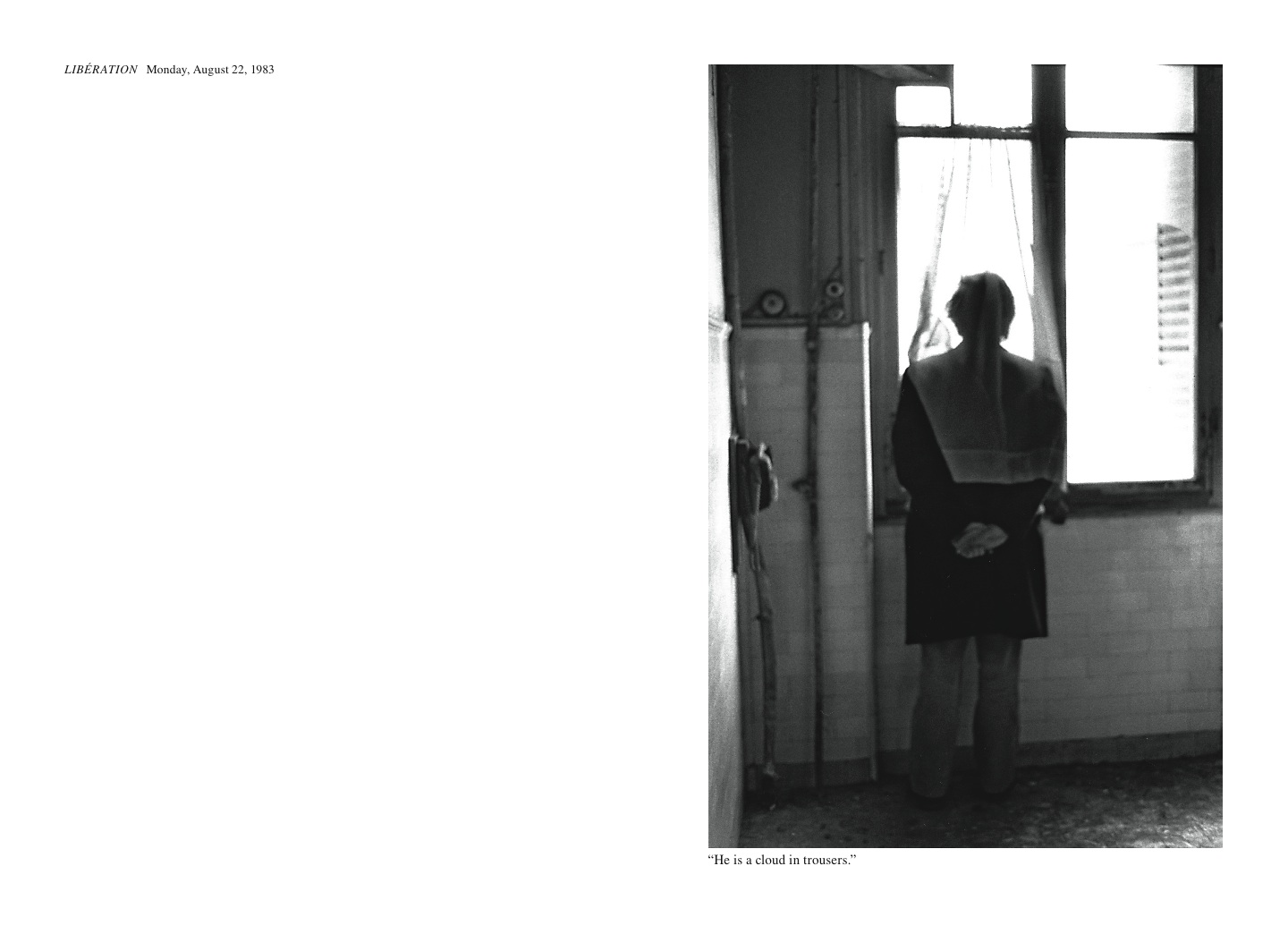

Conversely, Sophie Calle takes an approach that is not so matter-of-fact in her work, which should not be taken at face value – she does not tell her viewers how to look at or read her images, text or their combination. Moreover, if one separates her pictures from her text, neither will conjure up the connections in one’s mind as they do now – they exist as an inseparable whole. In the Address Book (1983), for instance, where the artist interviewed people from an address book that she found on the street in order to build an alternative portrait of its owner, we see a picture of a polar bear. Looking at the image, we would most likely believe that Calle took the image herself, as with all other images in the book. But there is something amiss – why would she travel to the North Pole? Maybe she made the image when she went there to bury her mother’s photograph, jewellery, and a bottle of French perfume. The bear is in its natural habitat so this takes the possibility of a zoo out of the equation. Only when we read the accompanying text do we realise that the picture is in fact a postcard sent by Pierre D. – the book’s subject – to the person whom Calle is interviewing. Jacques D., the interviewee, goes on to reveal some detail about what Pierre D. wrote on the back of the postcard and that it was sent to him from Norway where Pierre was leading a workshop. The image here is reliant on the text for clarification, which is antithetical to what Calle had done in her exhibition Parce Que (2018) at Perrotin Gallery in Paris. The visitor first encounters the embroidered text, which is required to be physically lifted to reveal the image in an interactive manner; thus Calle interchanges the order in which image and language are generally perceived in her work.

Roland Barthes argues that photographs are ambiguous messages without a code that need text to anchor their meaning. Calle deftly plays with this by the way she combines text and image – she presents a vernacular photograph and the text clarifies and puts it into context. On the other hand, the text without the image would be dry and probably nonsensical, therefore image and language in her work are co-dependent entities, as demonstrated in the example above. As James Agee writes in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, photographs are not illustrative – they and the text are “coequal, mutually independent and fully collaborative”.

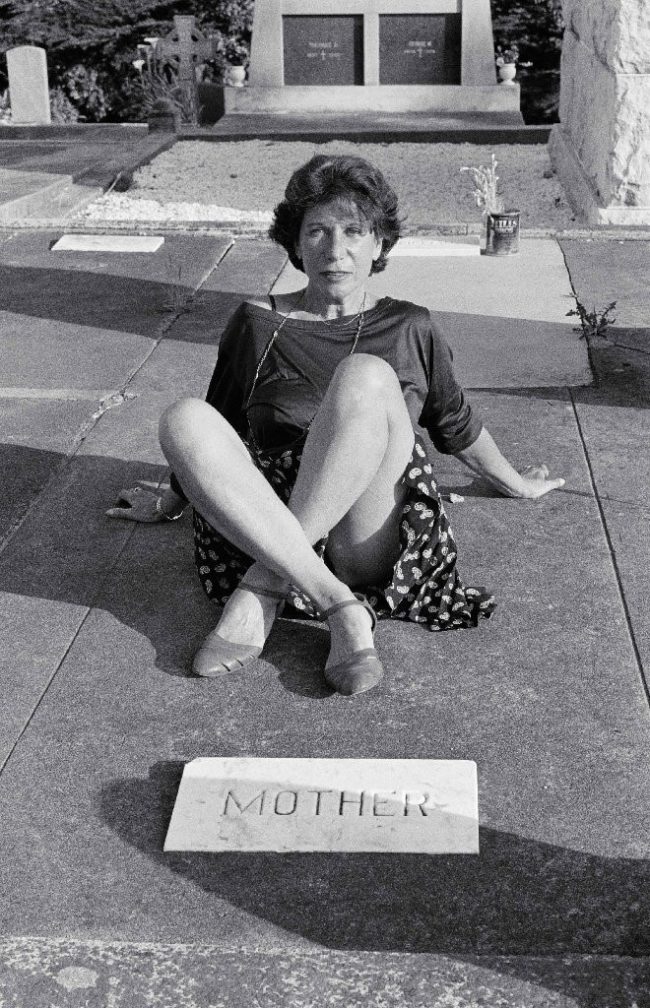

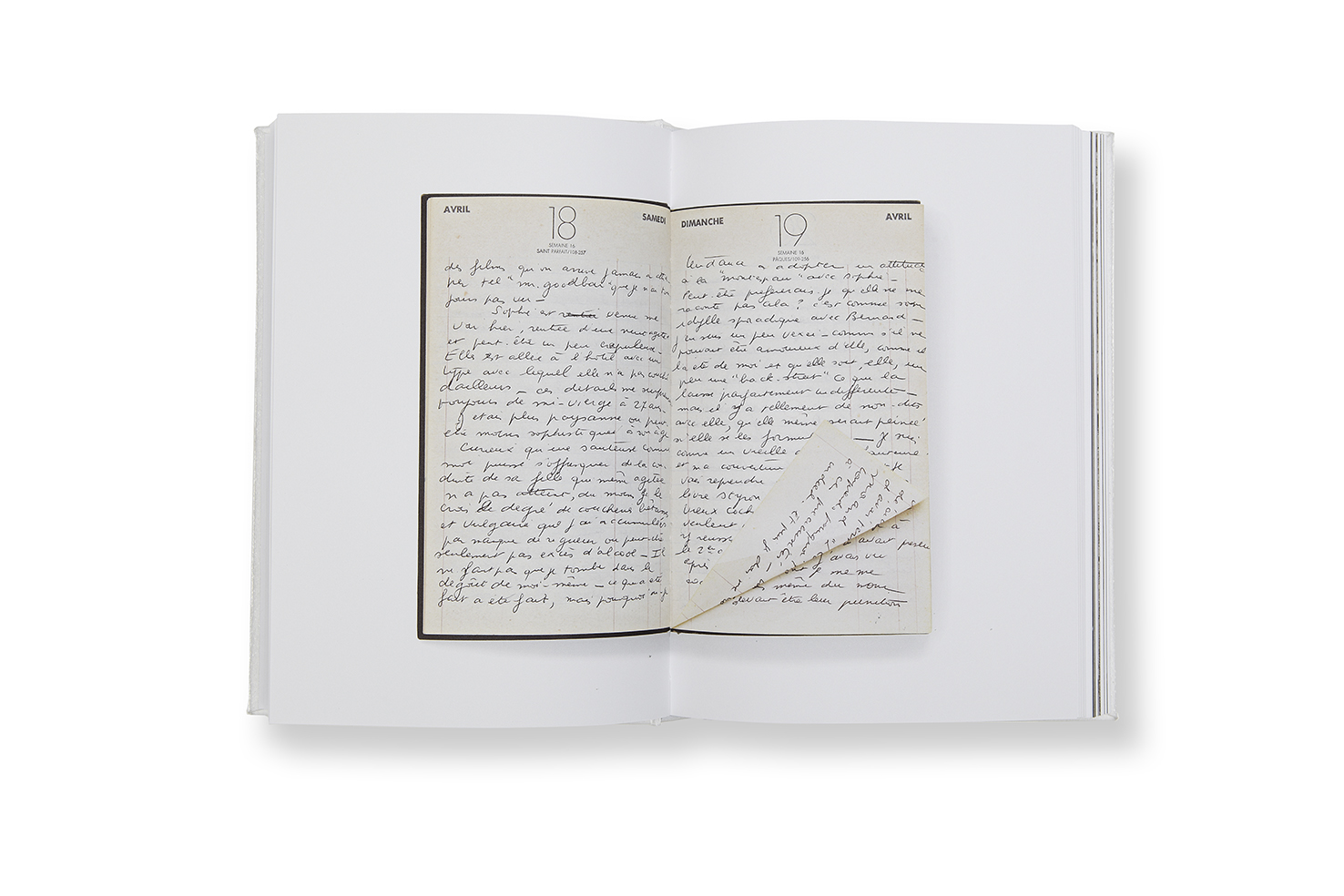

Calle is known for working with archival imagery. When her mother gave her a box full of old photographs, notes and diaries days before she died, true to her artistic self, Calle combined them in a book dedicated to her mum. The book, film and art installation is Calle’s way of honouring her mother’s wish to take the central stage in one of her daughter’s projects, as if one last chance to perform in the limelight. Rachel, Monique… (2012) is a combination of archival material (Monique’s old photographs) and new images taken by Calle in response to the fact that her mother was dying. She had given great prominence to her parent’s last word souci (part of the expression “don’t worry”) – she engraved it in marble, recreated it in lace, and created numerous other objects, metaphorically giving her the last word. Jacques Derrida interprets the archive as a “symptom of the repetition compulsion, which in turn is connected to the death drive”. In her paper, Natalie Edwards further elaborates that Derrida’s mal d’archive is an “uncomfortable, contradictory mixture of preservation and destruction that leads us to attempt to conserve memories and tempts us to discard or burn them.”

Rachel, Monique… is a eulogy to Calle’s dead mother and I would argue one of her most complex projects. It differs from her repertoire because it is about a family member – her mother has been a participant but never the subject of an entire body of work. It is an exercise in remembrance and memory. Photography is considered to be an essential tool in art therapy, one that helps us cope with pain and suffering. It enables us to keep those who are no longer with us present through holding onto their image (and, in this case, paraphernalia such as diaries) – this is especially true in the form of analogue photography, which is virtually a physical trace of the person, directly stencilled off the real like a foot print or a death mask. A photograph is the trace of light imprinted onto a sensitised strip of gelatine. It is a memory of an event that has been, a grain of sand from the past, and, as Barthes asserts in Camera Lucida (1980), it is inherently about death. It had been born out of the human desire to stop the flow of time and preserve it for posterity. Hervé Guibert claims that a photograph is “a less violent means of taking possession of something than a crime”. Similarly, André Bazin likens photography to the process of embalming the dead. I do wonder whether Monique will live in Sophie’s memory as the woman of flesh and blood or rather as the body of work that was born through her passing, which becomes a metonymy for the person.

As John Berger purports in Understanding a Photograph (2013),

” …what photographs do out there in space was previously done within reflection. Unlike any other visual image, a photograph is not a rendering, an imitation, or an interpretation of its subject, but actually a trace of it. No painting or drawing, however naturalist, belongs to its subject in a way that a photograph does. “

Calle is notoriously evasive when discussing the meaning of her work. She blends her art and life, seemingly unable or unwilling to distinguish between the two. In an interview with Louise Neri she refers to art as “a way of taking distance“. When she was creating the film of her mother on her deathbed, for example, she claims to have been more concerned about technicalities rather than emotions. This cool detachment, however, dissipated when she first saw the completed film exhibited, presumably because she experienced it both as a viewer and a woman who had just lost her mother rather than the maker of the work. Charlotte Cotton suggests that when an artist links their life to their artwork as inextricably as Calle has done, they protect the former from negativity.

” A new book or exhibition is rarely judged an outright failure because that would suggest a moral criticism of the photographer’s life, as well as their motivations. “

Calle’s esthétique de choix comprises of snapshot-style images that do not demonstrate the highest technical qualities – blown out highlights, underexposed shadows and out of focus portraits are prevalent in The Address Book. I would propose that this is an apt and considered choice as hyperreal imagery would be a distraction from an emotionally charged psychological work. This is in stark contrast with the tableaux of Jeff Wall or Andreas Gursky, for instance – the first emotion the viewer experiences when they encounter the work is one of sheer awe not only of the scale of the print, but of the image quality too. It is a sublime experience that words do not suffice to describe. Sophie Calle’s work is on the complete opposite end of the spectrum – it is intimate and emotional, it quietly asks you to hold it, almost always as a book, and experience it at your own pace. As Gil Pasternak observes, in the first six decades of the twentieth century, photographic scholars were primarily interested in high-brow artistic camera uses. Only in the late 1970s, when Calle embarked on her art career, did they consider photography’s vernacular properties.

Amateurism, Feona Attwood asserts, acts as a guarantor of authenticity. The perception of truth is something Calle has been working with from the beginning – she maintains that people ask her whether her stories are real so frequently that she opted to call one of her books True Stories (1994), which, understandably, convinced nobody. I would suggest that it is not for her to prove the veracity of her work – it is art, albeit with documentary traces, and it does not make serious claims to be an accurate representation of the author’s life.

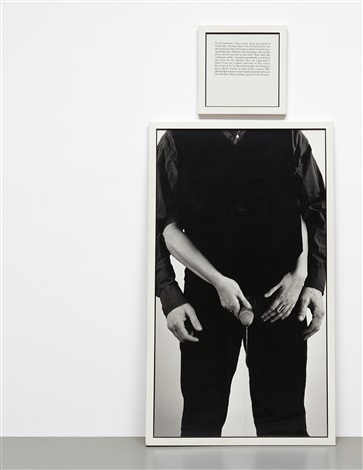

True Stories comprises of a selection of short anecdotes combined with images. Some are so weirdly wonderful and implausible, such as the image of the front of a man with his penis out that is being held by a female pair of hands, presumably the photographer’s. The caption elaborates that Calle had always wanted to be a man and she and her husband at the time made a ritual of her holding his penis when he went to the toilet. Allegedly the photograph was taken on the night they decided to divorce. It does make me question whether she made everything up and it is one big fabrication – the found address book on the street, the rummaging through strangers’ possessions in hotel rooms, the break up email from a boyfriend that spurred an entire art project, or the following of a stranger through the streets of Venice after having met him serendipitously at a cocktail party. It is at the back of my mind but then I immediately recall that she did buy a giraffe taxidermy and named it after her dead mother, she did bury her cat in a coffin and arranged a fully-fledged funeral with musicians du jour such as Bono and Pharrell. After all, she is a quintessentially French conceptualist that has conditioned her audience to expect anything.

Crucially, she is an artist, rather than a journalist, who does not have any moral or social obligations to tell the truth. Fittingly, Roland Barthes has suggested that it is not up to the author to decide the meaning of their work. In his essay “The Death of the Author” he declares that to give a text, or an artwork in this case, an author means confining it and imposing limits upon the multitude of ways in which it can be interpreted. Similarly, William Wimsatt advocates that the artwork is ‘’detached from the author at birth and goes about the world beyond his power to intend about it or control it’’. Authenticity is a concept that has been tied to photography since its very inception. We now know that a photograph does not equal truth and Calle further complicates this by introducing text.

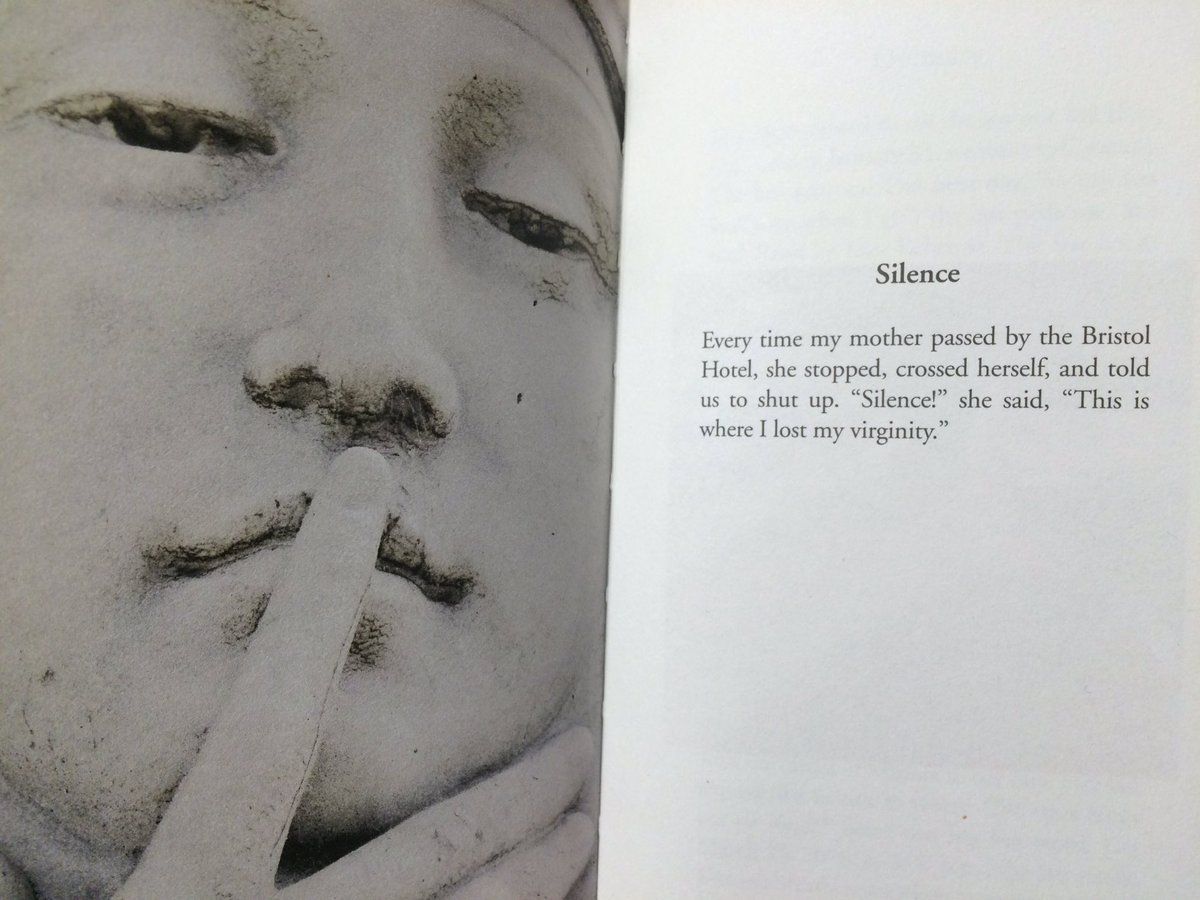

According to Victor Burgin, we rarely see a photograph in use that is not accompanied by language. He goes on to claim that even the uncaptioned photograph evokes language the moment it is looked at through memory, associations, labels. Photographs do not exist in a vacuum and they are always a referent to something outside of their frame. Jörg Colberg purports that photographs are “sticky” – the moment we see them, they stick to something in our mind from the past – a feeling, experience or another image. In other words, images conjure up subconscious associations in our minds that are a portal to our past. In True Stories we see a photograph of a sculpture in a trompe l’œil style with the woman’s forefinger on her lips. The text recontextualises it by revealing that Sophie’s mother used to demand silence when they walked by the spot where she lost her virginity. Has the photograph been used because the sculpture is from the referenced place, Bristol Hotel, or is it merely because it is depicting the “hush” sign, which corresponds to the text? Perhaps both.

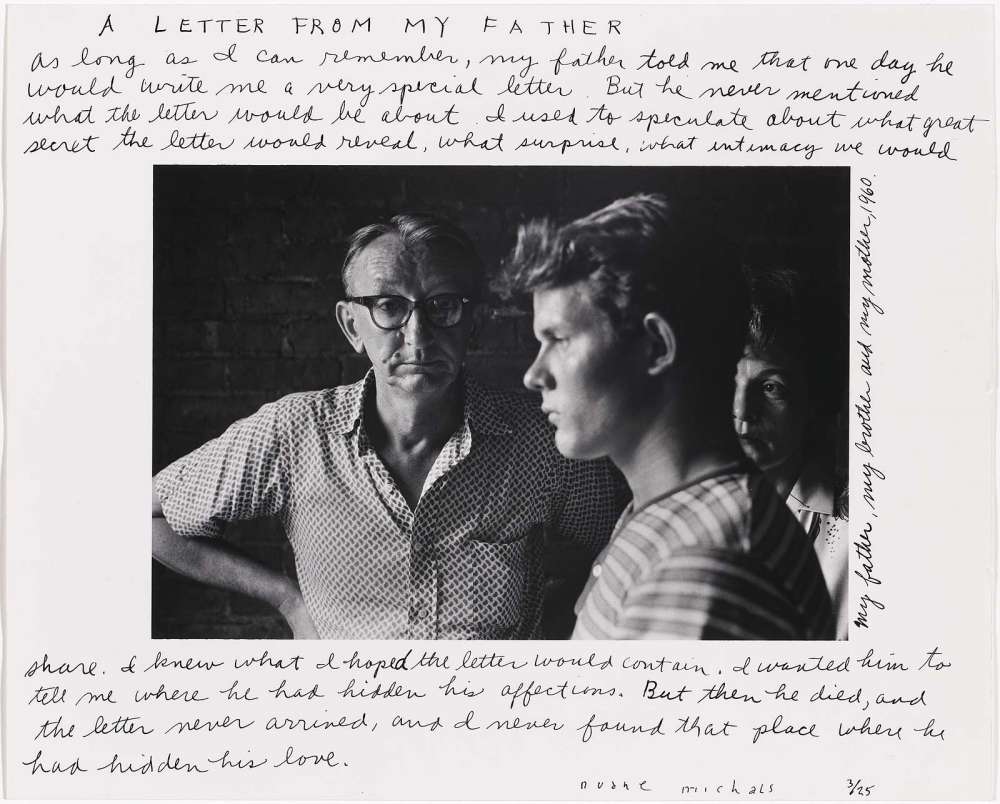

Comparably, other artists use a similar conceptual vocabulary to Calle’s. Amalia Ulman, for instance, performs in her Instagram project which commenced as a generic social media profile of a typical “babe” bathing in glamour, only to be revealed that it was all contrived specifically for the camera. Ulman’s fiction has common ground with Calle’s True Stories as neither presents any hard evidence of its verisimilitude, albeit Ulman admitted that it was in fact a lie. In contrast, Calle’s work is not designed for social media, but for the book form and, occasionally, the wall, meaning that the language and imagery is a lot subtler. Duane Michals’ photographs are supported by handwritten text on the borders – language anchors the photograph by gently pointing the viewer to the way in which it was intended to be seen and read. Nan Goldin creates an interesting push and pull between public and private, similarly to Calle, with the rawness of her photographs exposing sex, drug use and youth subculture in her celebrated book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985). “I don’t ever want to lose my real memory of anyone again” , she says in the introduction and this is part of the reason why she took those photographs. This is closely intertwined with Calle’s reasons for creating Rachel, Monique… – a memento of her mother’s extraordinary life. However, both Michals’ and Goldin’s work lack the typically French fineness and gentle humour. One constant feature in Calle’s work are her self-imposed rules, which she follows obsessively, be it not editing any of the responses she received from the women for Take Care of Yourself (2007), using her mother’s last word, no matter what it was, to create an expansive body of work, or inviting twenty-four strangers to sleep in her bed and photographing them. The idea is first and foremost and its manifestation follows lead – an inherently conceptual method of working.

” … all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. “

Analogically, Anouk Kruithof establishes an agenda and follows it arduously – for The Bungalow (2014) she isolated herself from the world to rework Brad Feurhelm’s image archive so extensively that the pictures acquire a new-found meaning. For Happy Birthday To You (2011) she interviewed ten psychiatric patients about their ideal birthday and organised it as best as she could – Kruithof spent the day with them and granted them the birthday wish closest to their hearts. Here we can see two different artists in terms of age, nationality, and sexuality, who nevertheless follow a similar path. Both prefer working in the book form, which allows the readers to explore the work in a slow and intimate way. Of course, the dissimilarities are just as many – Kruithof is very much interested in social media, pixels and digital technology while rarely using herself or her life as a prime subject, which is at odds with Calle’s deeply personal, autobiographical and resolutely analogue practice.

In conclusion, Sophie Calle has redefined what art is in today’s world by inventing a method of creating work that has become her signature style. Working extensively with the archive and dealing with themes such as loneliness, death and rejection, she is not easily classified – if one performs an online search, she appears as a writer; however, she is so much more than that. Having started her art practice in the late 1970s, its raison d’être is to address numerous issues – what is privacy and what are its temporalities in its current state? Can good art emerge from a pain-free, enjoyable life? What arises when one merges image with text, even if the two separate components are nothing exquisite on their own? Calle does not provide direct answers and she remains an enigma.

Zak Dimitrov is a London-based photographic artist. After successfully completing his art foundation in photography, he moved on to study BA (Hons) Photography from which he graduated with First Class Honours in 2015. He earned an MA in Photography Arts at the University of Westminster, further developing his work on memory, mortality, loss and time.

Zak has worked at various art schools, galleries and photo labs as well as contributed to written publications. He continues to explore his interests, spanning from history of art to curating, writing, video work and art presentation.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025