Kyler Zeleny: Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series and new book, Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle by Kyler Zeleny.

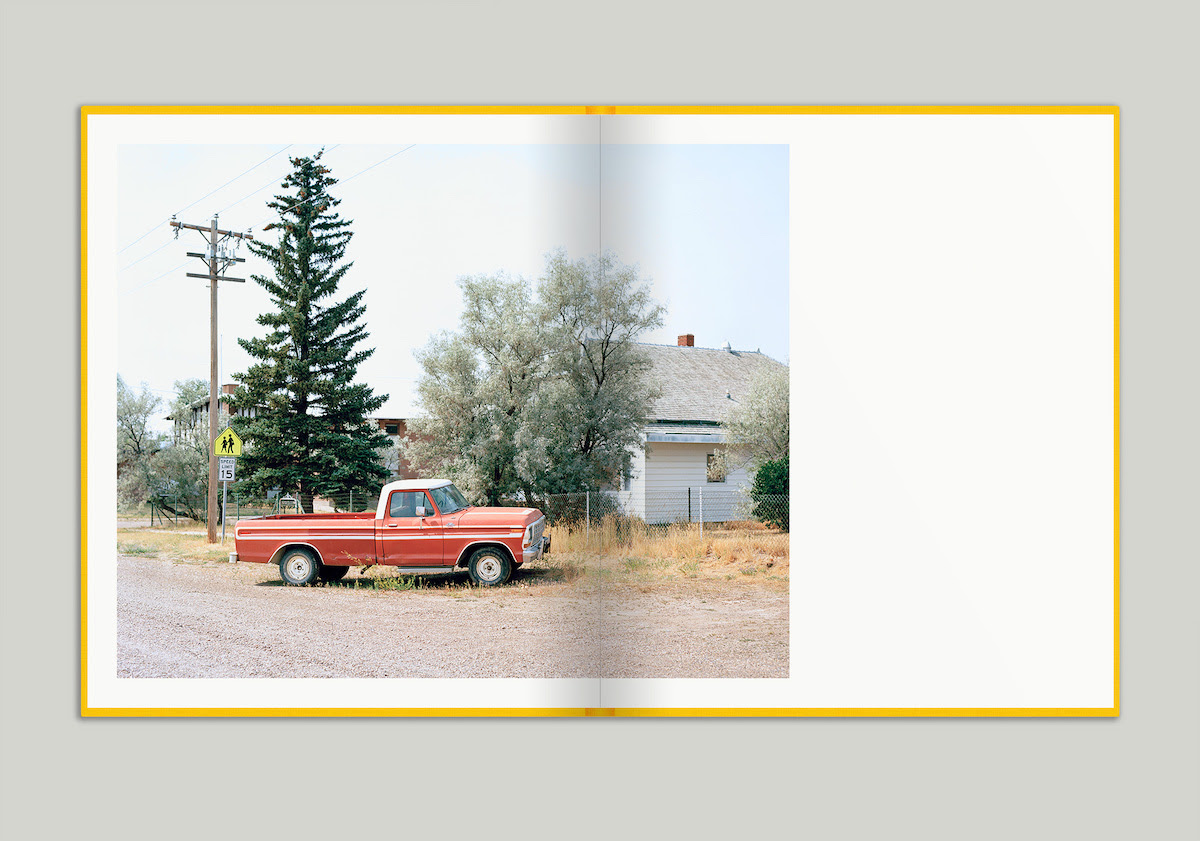

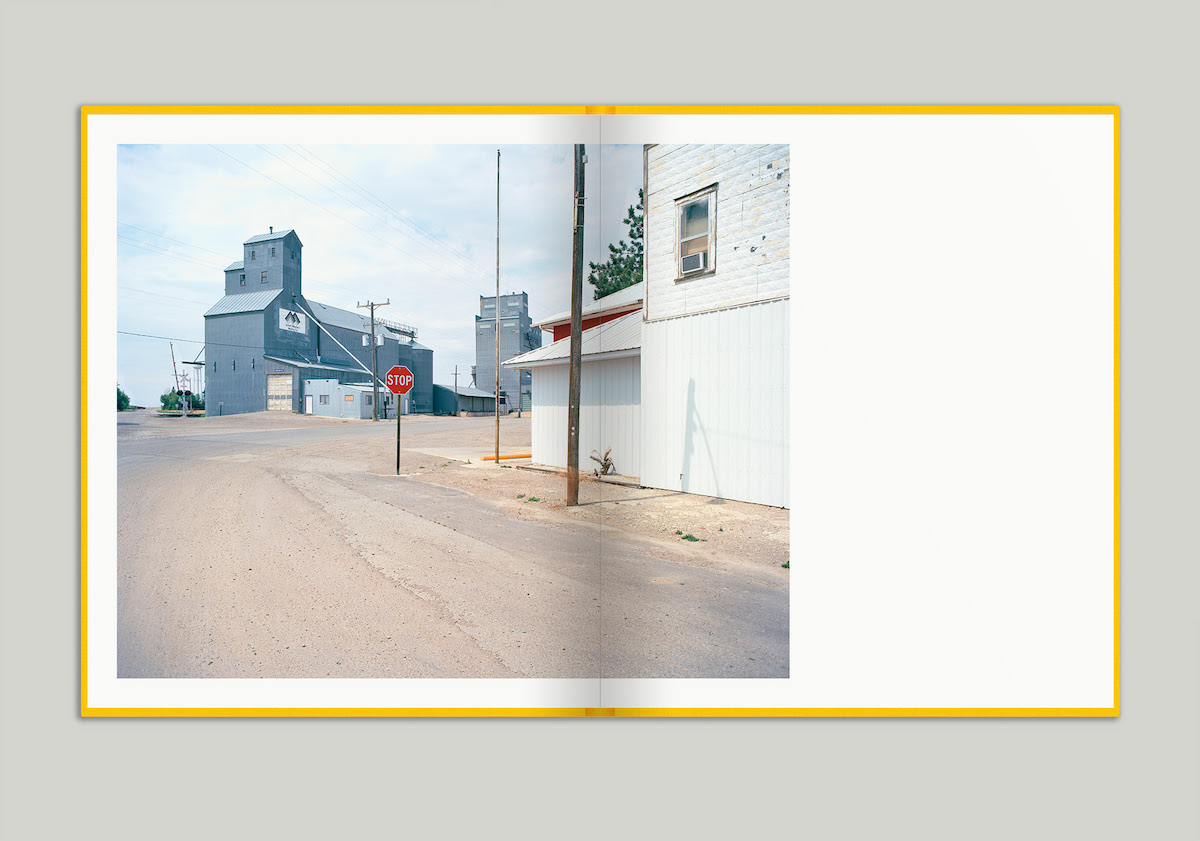

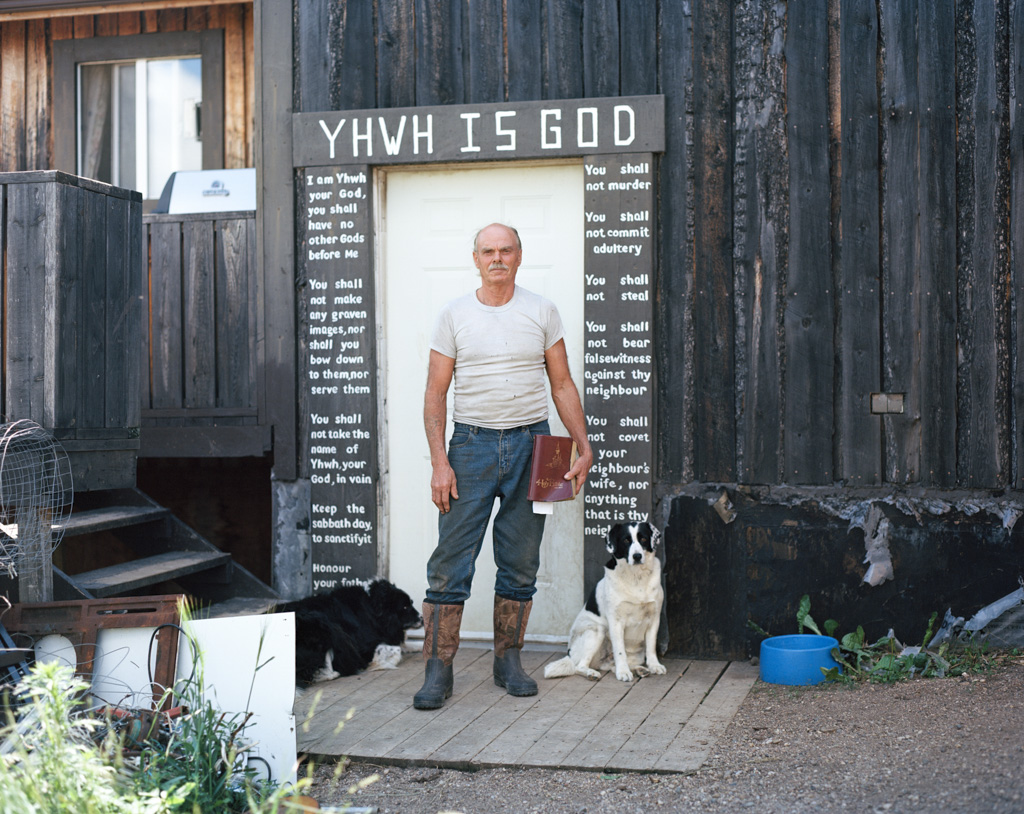

In the space of four years, Kyler Zeleny travelled the prairie lands of North America, driving over 15,000 km in the process to photograph and document their current realities. The prairies is an extensive region encompassing parts of both Canada and the U.S. suffering from a loss of heritage and uncertain about its future as society continues to move in the direction of mass urbanisation. The project presents the space as an understudied region, a beast upon itself, a unique meeting of landscape, industry, and most importantly, people who are a resilient breed created by generational lessons in fortitude and fortuned circumstance.

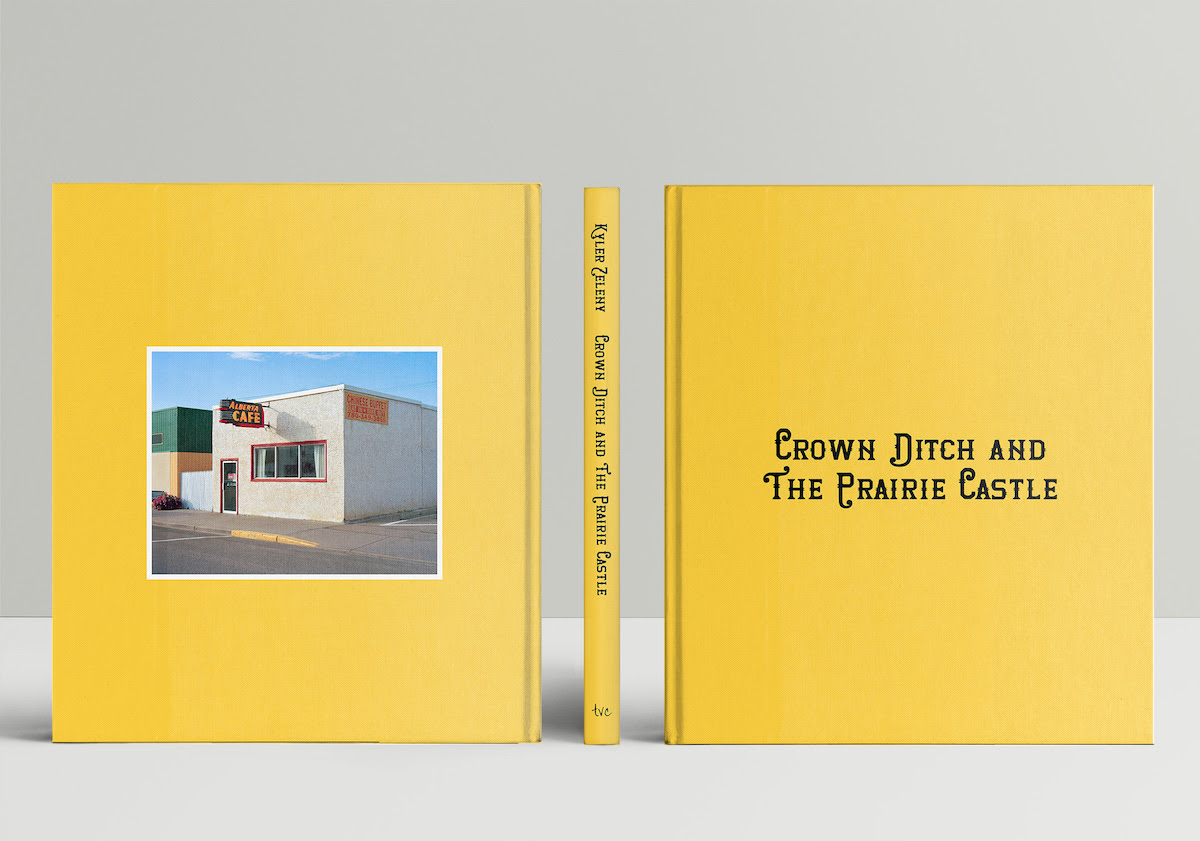

Crown Ditch & The Prairie Castle is the spiritual successor to Zeleny’s 2014 Out West, also published by The Velvet Cell (sold out).

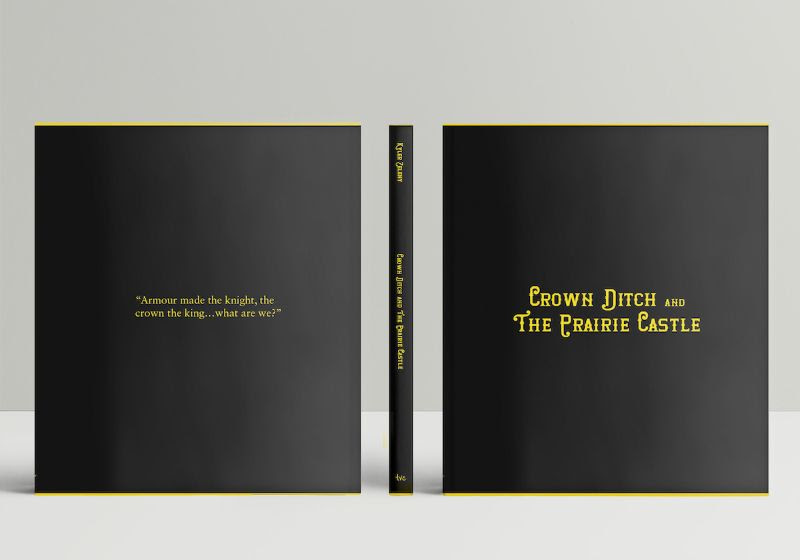

Pre-orders for the Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle Collector’s Edition book are currently available at The Velvet Cell. The Limited edition of 75 copies is only available to online backers.The Collector’s Edition includes: a Signed & Numbered Fine Art Print on Hahnemuhle Baryta (scroll to bottom), a signed Copy of the Book, a Collectors-only Dustjacket (black w/ gold foil), Credit as a backer in the book, and a Handwritten Postcard with thanks from the artist.

Kyler Zeleny (1988) is a Canadian photographer-researcher and author of Out West (2014), Found Polaroids (2017), and Crown Ditch & The Prairie Castle (2019). He holds a masters from Goldsmiths College, in Photography and Urban Cultures. His work has been exhibited internationally in twelve countries. He is a member of the Association of Urban Photographers (AUP), a guest editor for the Imaginations Journal for Cross-Cultural Image Studies and a guest publisher with The Velvet Cell. Kyler is currently a doctoral candidate in the joint Communication & Culture program at Ryerson and York University and teaches at George Brown College. He occupies his time by exploring photography on the Canadian prairies.

Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle

“Armour made the knight, the crown the king…what are we?”

At the turn of the 20th Century North America’s last great land rush took place in the Canadian West. It was on the prairies that the soil made the farmer, the herd the rancher. A lingering question for the sons and daughters of the ‘last great west’ is what, or who, are we? Overshadowed and often visually conflated with its neighbour to the south, we forget to turn our gaze to the Canadian prairies. Essential to understanding this region involves forgetting the American Frontier and forging a new account of space.

The area was settled by a unique brand of hardened frontiersmen—cowboys, ranch hands, miners, farmers, and outlaws—the dirty and determined, the persistent sludge at the bottom of every gas tank. These good ol’ boys were chasing the exalted allure of a grand landscape defined by its apparent nothingness, a landscape mystical by its inadequate representation, mystery, and whisper of being the last ‘Promised Land’.

Gone are the early remnants of the Canadian prairies but its legacy still endures. Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castledocuments the places and people of the last great ‘proving out’. The project presents the space as an understudied region:a beast upon itself, a unique meeting of landscape, industry, and most importantly a breed of resilient people created by generational lessons in fortitude and fortuned circumstance.

Daniel George: You have dedicated a lot of time to photographing the Canadian prairies. What keeps drawing you back?

Kyler Zeleny: It’s fertile ground here and there are surprisingly few photographers doing long-term projects on the prairies, so there is definitely a lot of opportunity to explore and help shape ideas about the region. The prairies are also my spiritual home; having grown up on a farm in Alberta I’m accustomed to big skies, wide horizons, and the folk that dwell there. I also think photographing and writing on the prairies helps me understand the space better, yes this is a place I grew up but I’m far from coming to terms with it. I also believe that those outside of the region should have a better understanding of what and who is on the Canadian prairies and these projects are my contribution to that conversation.

DG: In your statement, you refer to this region as the last “Promised Land.” Is this a common mindset of residents? In what ways do they interpret this to mean?

KZ: It may not be a sentiment that residents themselves internalize, perhaps earlier generations had a better understanding of the risk and reward of prairie living. It was the greatest land rush in history and by some measures it utilized the largest marketing campaign ever to attract settlers. The prairies were initially thought and interpreted as barren and banal but slowly the myth was produced that Western Canada was fertile and offered promise from those looking to find a better life, to own land and be their own boss. People from all over Europe and America came to ‘prove the land’ and take advantaged of opportunities to prosper in the region. Some areas of the region were not as fertile as billed while others provided great promise, some came and attempted to farm lands which were too arid, farms failed, towns failed, people moved. In other areas, and aided by technology, farmers produced great returns and were able to expand their farms, help sustain their communities and put down long-term routes. For the latter this would be seen as a promised land.

DG: Is it possible to completely forget the American frontier when considering that of Canada? How might one go about viewing these photographs independently of what you describe as an overshadowing influence?

KZ: Making a call to forget the American frontier is my attempt at making a provocative statement. A lot of the cultural references of the Canadian West are built on the American West, either through writing, photography or the rampant Hollywood machine. I remember when I first started photographing on the Canadian prairies people would discuss my images as if they were American simulacrum, images no different than you’d find south of the border. That made me think, how can Canadian photographers assert a unique regional sense of place if we are benchmarked against a cultural juggernaut with its own mythology, history and imagery? I’m still working on the answer, but what we can do is realize that in North American we often graft a dominant idea of space onto lesser spaces. Acknowledging that is perhaps the first step to understanding that there is no standard for what we do and create on the Canadian prairies.

DG: You mention the resilience of the individuals whom you photograph, which I assume must be a defining characteristic of anyone involved in rural industry. Describe your experience working with them.

KZ: There is something special about the prairie spirit. At its core is the idea of Frontierism and perseverance. Arriving in covered wagons or on a newly established railway with only a trunk of goods, they lived in sod houses made of mud and manure struggling to make a new life in an area that had never seen large infrastructure or mass settlement before. That spirit carries forward and helps define the region. The prairie summer is a beautiful thing, nice and dry, not too hot, but its winters are isolating, cold and crippling. You need thick skin here and the settlers, following in the footsteps of First Nations people of the region, have developed a resilience that is admirable. I’ve experienced this resilience in farmers dealing with a tough harvest or small town dwellers holding on to the remnants of their dwindling town.

DG: Crown Ditch and the Prairie Castle is part two in a trilogy started by Out West. Why did you feel it necessary to divide the projects in this manner, and how does each contribute to the overall dialogue on Western Canada?

KZ: When Out West came out in 2014 I didn’t know the project would become more than a single artist monograph, the trilogy idea developed organically. As soon as I finished with Out West I felt there was a lot more to say and do. Out West was about documenting the smallest of the small towns (1,000 or less inhabitants) and was largely about photographing the towns and the idea of people’s presence through their absence. Crown Ditch expanded that scope to include environmental portraits of rural dwellers and images of the landscape along with the towns (10,000 or less inhabitants). I’ve started to work on the final chapter of the trilogy, titled Bury Me in the Back Forty which focuses on a deep-dive into my home town of Mundare, Alberta, an equally unique and typical rural town. This project uses more of a post-photographic approach stepping outside of a traditional documentary approach to include the images of others, modified archives and objects to tell a complicated story of place. Each of these chapters does something different and says something different but are all related to one another and represent a natural progression of thinking and creating. After this I’ll be switching to another prairie trilogy that looks at specific aspects of rural culture. You can probably tell the prairies are my spiritual home.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Riley Goodman: Art + History Competition Honorable Mention WinnerApril 4th, 2025

-

Rachel Nixon: Art + History Competition Honorable MentionApril 3rd, 2025

-

Oleksandr Rupeta: Art + History Competition Second Place WinnerApril 1st, 2025

-

Jared Ragland: Art + History Competition First Place WinnerMarch 31st, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Researching Long-Term Projects with Sandy Sugawara and Catiana García-KilroyMarch 27th, 2025