América Latina Week: Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

This interview was written with the kind help of and in conjunction with Elena Gálvez Mancilla – Mexican historian and sociologist; a researcher on the Amazon and indigenous culture, interested in the image as a historical source, photography enthusiast and environmental activist. The post is featured in both English and Spanish. The Spanish version follows the English.

©Erica Bohm

Erica Bohm was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1976. Graduated in the School of Fine Arts Prilidiano Pueyrredón. She was part of the Postgraduate Artists program and Film Laboratory at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in 2009 and 2012, coordinated by Inés Katzenstein, Jorge Macchi, Martín Rejtman and Andrés Di Tella.

She was selected to participate in the Art Residency in Antarctica, Sur Polar Program (2015); Atelier Solar, Madrid, España (2019); San Martín-Móvil, San Martín de los Andes, Argentina (2014) and the Mapping Exchange: Artists Residency Programs, Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, U.S.A. (2009).

She received the following distinctions and prizes: Creation Grant of National Fund of the Arts (2008 & 2017) and also the Trama Grant (2004 & 2005); Second Acquisition XXII Klemm Prize, Federico Jorge Klemm Foundation, Buenos Aires (2018); Third Acquisition Itaú Artes Visuales, Itaú Foundation, Buenos Aires (2018); Second Acquisition Award LXX National Salon of Rosario (2016); Mention Lucio Fontana Award (2013); Petrobrás Award Mention, Buenos Aires Photo (2011); Third Prize at MAC Digital Paradigm Award (2007); First Prize at Lebensohn Foundation Prize and the Second Prize in Curriculum Cero, Ruth Benzacar Gallery (2006), among others.

Also, she has made individual and collective exhibitions in different institutions and galleries, such as Queens Museum, New York; California Museum of Photography, Sweeney Art Gallery, and Culver Center of the Arts at UCR ARTSblock, California; Hyde Park Art Center, Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Museum of Contemporary Art of Bogotá, Bogotá, Colombia; MAMBA, Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires; MAR Museum of Contemporary Art of Mar del Plata; Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires; Proa Foundation, Buenos Aires; Sívory Museum, Buenos Aires; Instituto Cervantes, San Pablo; J.C. Museum Castagnino, Parque España Cultural Center, Rosario; Pasto Gallery, Buenos Aires; The Mission Gallery, Houston and Chicago; Baró Gallery, San Pablo; among others.

She is represented by Pasto Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

©Erica Bohm

How did you start doing photography? What is your process?

It started when I was studying at UNA “Universidad Nacional de las Artes”. During my last year, there was a subject which allowed experimenting with various visual approaches. I began playing with coloured objects and taking photos of them. At the same time, my cousin had a photo lab at home and that is how I first explored black and white photography. My studies resulted in experiments; I never, formally, studied photography. I did participate in many clinical work workshops guided by photographers.

I experiment a lot and I think I am very much outside the norm when it comes to the correct use of photographic tools, sometimes this might help and others not so much. There were many times in which I thought of these experiments as mistakes. Namely, with Moonlight, I imagined super clean lines on the photographs. I had already discarded more than 100 pinhole photographs; to me, they were mistakes, but with time I came to notice that the images were quite striking. Sometimes, in photography, what is considered a mistake might become an asset. I saved them due to intuition, the path of intuition is the one that allows me to create projects of greater complexity. This project lasted 3 to 4 years and it varied a lot during the period’s course.

©Erica Bohm

An important aspect of your work is time; namely, in Calendario, there is the repetitive act of capturing the sky every day during the period of one year. I am very interested in your creative process. Could you tell us more about it?

Every project has its own lengthy experimentation and work process. Generally, I cannot achieve short projects, they need time to develop. Moonlight began in a residency in San Martín de los Andes, coordinated by Solana Molina and Alejandra Aguado. They have established “Móvil”, a brilliant art project here in Buenos Aires. The private collectors who offered this residency decided only to invite women artists and on that first edition, I travelled with Rosana Schoijett. Thus, they were aware of how women have been less privileged in the art world. Art is still a very patriarchal institution, a male artist from my own generation may sell at three times the amount because of this factor. In addition to the lack of possibilities, there is an important economic aspect.

However, as I was saying, I took a portable telescope and began thinking about how to capture the light that was being emitted by the stars. Taking that into account, I built different pinhole cameras made with precarious card boxes. I love that through pinhole photography one can create something out of nothing. I worked at the residency for a month and a half and later in Buenos Aires, specifically, during full moon periods. During all those years, I collected a lot of material and I liked seeing them all together. Thus, the difficulty of thinking about how to exhibit them. I worked with Benedetta Casini, the art curator of the show at Galería Pasto. Together, we saw the possibility of exhibiting them in a wooden box and not on the walls with the objective of creating something closer to the actual making process of the photographs.

Representing the plurality of nights is interesting, each moment is different and that is what you perceive by looking at the series. There is also the Sun’s presence, the stars, the Moon that does not have a light of its own; I often feel that this project talks more about the Sun than the Moon.

I esteem how this week’s artists have sought to represent that which is not visible, it is not easy to do so.

Who are the artists that have inspired you or have influenced your work?

For me, Walter de María and Robert Smithson are artists that I keep revisiting; they have both worked on landscapes from different perspectives. Regarding photography, Andrea Ostera, a photographer and educator from Rosario has had a strong influence on how I see things. I have studied with Gabriel Valansi and Jorge Macchi and admire them very much. A more obvious choice, but an artist who I love, is Magritte. They are all artists who make me analyse and reflect a lot on our reality. I would also add Vija Celmins, Rosângela Rennó and Pierre Huyghe. Some very close colleagues too; Sofia Bohtlingk, Marcela Sinclair, Cecilia Szalkowicz, Nicolás Martella and Martín Sichetti.

©Erica Bohm

What do you want to achieve with your photographic work?

In relation to what I am capable of shooting, I always thought that photography was an interesting medium because of its relation to fiction and reality. Photography is a moment’s fragment. I thought that capturing an image on a light-sensitive paper was amazing and very simple. Yet, it was capable of capturing the complexity that is the passage of time. Photography manages to capture, poetically, the passing of millions of years. I always thought about what I was not able to shoot. For example; the universe, all the universe’s time. That was my modest tale; I cannot capture the universe, but I am able to fix a night’s instant, which encloses that period’s complexity and everything that is not shown in that time too.

©Erica Bohm

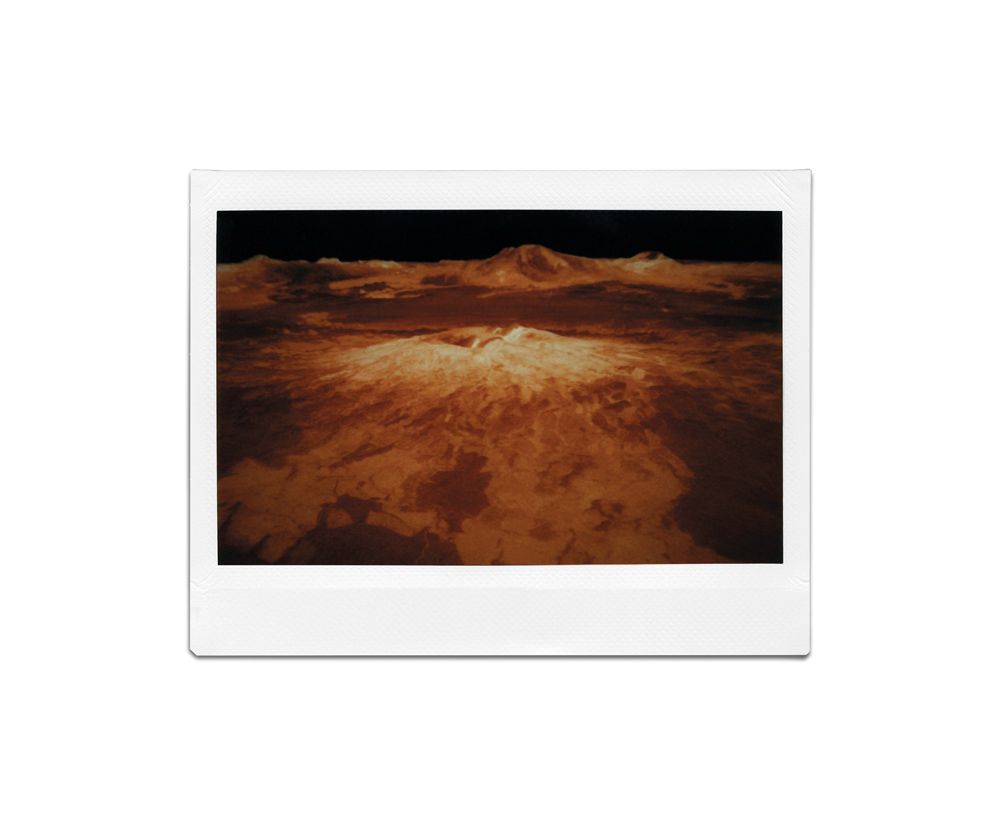

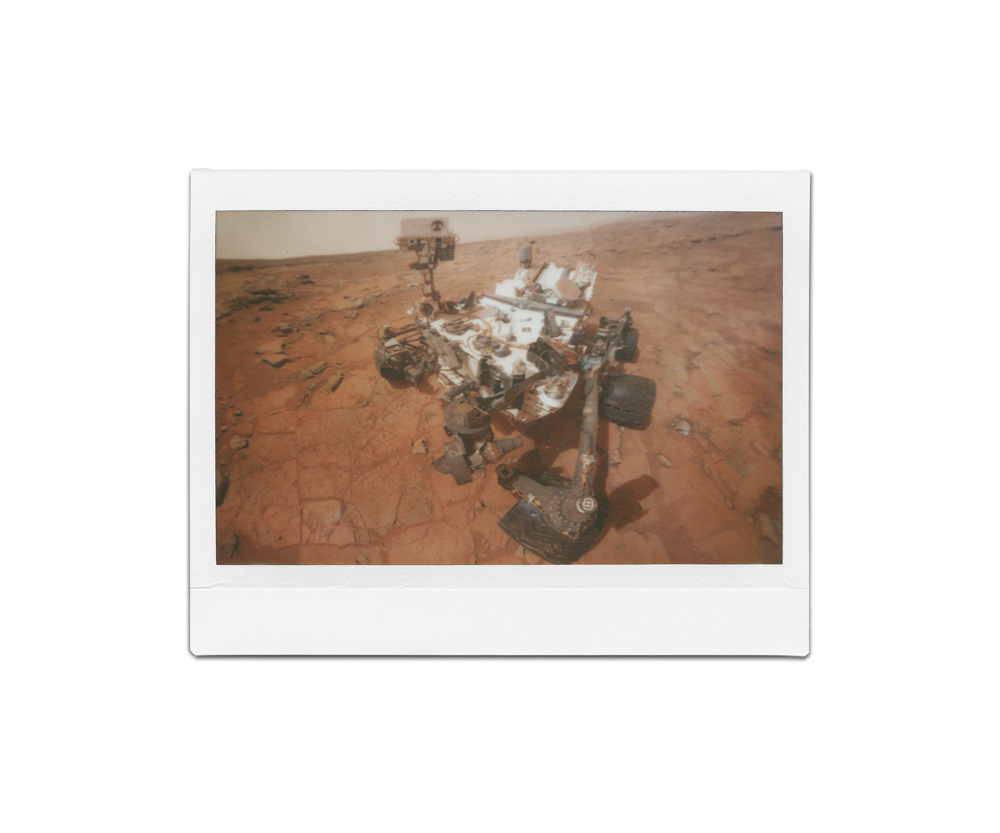

For Planet Stories, you employ Instax photographs to represent astronomy-related images from different institutions. It made me think about the evidence of us humans on space, reflected on the astronaut’s shadow. Could you develop on your use of the Instax?

I have been interested in astronomy and science fiction for many years now. When institutions opened digital libraries and ever since the development of digital photography, I found the entire Apollo mission archive. Usually, images produced with the use of telescopes are constructed by stacking different photographs; those images could never be visible to the naked eye, I find it fascinating. The camera, which accumulates light, is a tool that far exceeds the human eye.

There is always doubt with regard to the authenticity of the image, even before digital editing. As if looking with our own eyes were an affirmation of what is real. I thought about translating this trust issue to a photographic project by using photographs from space. Namely, the human presence in images taken by astronauts or spacecraft like the Curiosity in Mars and the Magellan in Venus. That is how, thinking about our need for evidence through presence, I decided on the Fujifilm Instax photographs – they are like Polaroids. What better way to position ourselves in space? The same camera develops the object, there is no need for processing.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

I am aware that you studied Visual Arts, painting. What are your working tools?

There are too many, it’s very stimulating to search for a physical medium to occupy one’s ideas. My tools vary a lot. In Moonlight, I used pinhole photography but the display included a book with conversations between astronauts. The text included transcribed conversations from the Apollo 11 mission. I abstained from technicalities and kept the most subjective and poetic segments on a conversation on photography.

I believe that each project must have its own display and different tools in order to be part of my production and an object of the world; in the end, these are produced objects. A fundamental tool is having ideas and knowledge; for me, there is also astronomy and literature. There are many intangible tools.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

Elena: Coming back to the use of different materials and techniques; there is a contradiction between the time contained and represented on the images, including the long conceptualizing and creation process, and the immediacy of the Instax. With very simple tools, you invite us to see very strange worlds. Further, they do not relate to any known imagery and I believe that has to do with the making process. Could you elaborate on these two topics?

When it comes to temporality, it really does depend on the project, some take 8 hours and others take 2 or 3 years. The creation of crystals is very different from pinhole photography. Even if the materiality of the crystals I have made are not photographic, nor photographs, they have time as a common feature. Both, the crystals and photographs are experiments that work with time – they are nourished by time.

I am not interested in immediate processes, I am drawn to long projects because of my concerns regarding space and humanity’s finitude. The universe is millions of years old, there is something about this that resonates with me. For El cristal perfecto, I tried to replicate geological processes that usually take millions of years, in two years. It is my small contribution in time; in my own finitude, I do not know how many I will be able to create.

Elena: It is quite amusing, this visual narrative that creates a dialogue between science fiction and poetry. Where does the need to conjugate those worlds come from?

An idea that appeals to me is the poetics of science, parallel universes and the possibility of time travel. It is very interesting to think about these theories in their most basic forms, science fiction and literature are two artistic tools that help us comprehend them. With that narrative, I wanted to generate images in the spectators’ minds; a third, constructed image and an active spectator. I want to generate more questions than answers, that is what occurs when I look at the sky. People will ask themselves: How did she do it? Did she take that photo? These queries create an active individual’s gaze. That is why we are artists, to generate questions.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

What inspires you about Latin America?

Our revolutionary spirit for taking care of our continent, which is being crushed by fires and patriarchal policies from world powers. We come from a site that has many natural resources, diversity and voices. Latin America is a strong force that ought to be protected by those who live in this territory. That is what this pandemic has demonstrated, we should take care of ourselves and produce locally. It is important to be connected with the rest of the world, but we mustn’t lose our understanding of our locality. If not, our territory will be extracted until it is all gone.

ESPAÑOL

Esta entrevista se hizo con la amable ayuda de Elena Gálvez Mancilla. Historiadora y socióloga mexicana, estudiosa de la Amazonia y la historia indígena, interesada por la imagen como fuente histórica, amante de la fotografía y activista ecologista.

©Erica Bohm

Erica Bohm nace en Buenos Aires, en 1976.

Egresada de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes Prilidiano Pueyrredón. En el año 2009 fue becaria del Programa de Artistas y en el 2012 del Laboratorio de Cine en la Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. Recibió la Beca de Creación Fondo Nacional de las Artes (2008 y 2017) y también la Beca Trama (2004 y 2005).

Fue seleccionada para participar de la Residencia Atelier Solar, Madrid (2017); Residencia de Arte en Antártida (2015); Residencia San Martín-Móvil, San Martín de los Andes, Argentina (2014) y del Mapping Exchange: Artists Residency Programs, Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, U.S.A. (2009).

Ha realizado muestras individuales y colectivas en diferentes instituciones y galerías, como ser, Queens Museum, New York; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Bogotá, Colombia; Fundación Proa, Buenos Aires; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; MAMBA, Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires; Museo Sívori, entre otras.

Recibió las siguientes distinciones: Segundo Premio Adquisición XXII Premio Klemm, Fundación Federico Jorge Klemm (2018); Tercer Premio Adquisición Itaú (2018); Mención Premio Fondo Nacional de las Artes, Buenos Aires (2018); Segundo Premio Adquisición LXX Salón Nacional de Rosario (2016); Mención en el XVIII Premio Federico Jorge Klemm a las artes visuales (2014); entre otros.

En el 2015 viajó al Continente Antártico, a las Bases Esperanza y Marambio, allí realizó varios proyectos en relación al paisaje para pensar nuevos modos de interactuar con la luz y el tiempo. En el 2018 viajó al Polo Norte, más específicamente al archipiélago de Svalbard. En ambos viajes se dedicó a investigar diferentes fenómenos naturales, atmosféricos y también geomagnéticos.

Sus intereses también giran alrededor del imaginario sobre el espacio y sus múltiples representaciones: imágenes de paisajes de lugares soñados y casi no explorados, ni experimentados por el hombre pero formadas a partir del cruzamiento de distintos relatos como las novelas y films de ciencia ficción, junto con diferentes teorías científicas. Esta ficción sobrevuela la historia de la conquista espacial, la construcción de la figura del astronauta como héroe del siglo XX, la circulación de las imágenes retratadas por las sondas de la más avanzada tecnología, la metáfora de la búsqueda del espacio exterior como escape de la realidad y, ante todo, la excusa para retratar el viaje que las imágenes hacen entre nosotros, hasta o desde nosotros.

¿Cómo empezaste a hacer fotografía?

Empecé en la UNA (Universidad Nacional de las Artes). Durante el último año, había una materia que permitía la experimentación de varias situaciones visuales. Empecé jugando con objetos de colores y sacándoles fotos. A la par, mi primo tenía un laboratorio fotográfico en su casa y así empecé a explorar la fotografía en blanco y negro. Los estudios devinieron en experimentación porque nunca estudié fotografía formalmente. Hice talleres, orientados y con fotógrafos, sobre clínica de obra.

Siento que lo que hago es experimentar y que estoy muy por afuera de lo que sería el uso correcto de las herramientas, a veces esto me ayuda y a veces no. Consideraba que muchas de esas experimentaciones eran errores. Para Moonlight, por ejemplo, al principio yo me imaginaba unas imagenes súper clean y una línea perfecta. Había descartado más de cien fotos, que para mí tenían errores. Después, con el paso del tiempo y al observar de nuevo el material, me dí cuenta de que era muy rico. A veces, lo que se considera un error en la fotografía, puede convertirse también en una ganancia. Por intuición las archivé, el camino de la intuición es la que me permite y me ayuda a hacer proyectos de mayor complejidad. Este trabajo duró de 3 a 4 años y fue variando mucho a lo largo de ese período.

©Erica Bohm

Un aspecto importante de tu trabajo es el tiempo. Por ejemplo, en Calendario, se da el acto repetitivo de capturar el cielo todos los días durante un año. Me interesa mucho tu proceso creativo, quisiera que nos cuentes sobre su desarrollo.

Todos los proyectos tienen un proceso largo de experimentación y de trabajo. En general, no puedo hacer trabajos cortos, tengo que darles tiempo para que se vayan generando. Moonlight comenzó en una residencia en San Martín de los Andes coordinada por Solana Molina y Alejandra Aguado. Ellas organizan Móvil, un proyecto brillante de arte contemporáneo, acá en Buenos Aires. Los coleccionistas que ofrecían esta residencia invitaban únicamente a artistas mujeres, en esa primera edición viajamos con Rosana Schoijett, ellos tenían en cuenta que las mujeres hemos sido las menos privilegiadas en el mundo del arte. El arte sigue siendo una institución muy patriarcal, un artista de mi generación puede ganar el triple por sus obras. Además de la falta de posibilidades, está un aspecto económico importante.

Continúo, llevé un telescopio portátil y a partir de eso pensé mucho sobre como capturar la luz emitida por las estrellas. Para esto, construí diferentes cámaras estenopeicas realizadas con cajas de cartón bastante precarias. Me gusta que en la fotografía estenopéica, a partir de nada, puedes crear todo. Trabajé en la residencia durante un mes y medio y luego en Buenos Aires, específicamente, durante los períodos de luna llena. Durante todos esos años, había recolectado mucho material y me gustaba la idea de poder ver todas las fotografías juntas. Después, el desafío fue pensar en cómo exponerlas. Trabajé con Benedetta Casini, la curadora de la muestra en la Galería Pasto, vimos la posibilidad de montarlas sobre una caja de madera y no sobre la pared con el objetivo de crear algo más cercano al proceso de realización de la fotografía.

Creo que es interesante representar la pluralidad de noches, cada uno de esos momentos es distinto y eso se percibe en la serie. También está la presencia del sol, de las estrellas, ya que la Luna no posee luz propia; siento que este trabajo habla más del Sol que de la Luna.

Me gusta como lxs artistas de esta serie, de entrevistas de América Latina, tienen un punto en común: representar lo que no es visible.

¿Qué artistas te han inspirado o han tenido una influencia en tu trabajo?

Para mi Walter de María y Robert Smithson son artistas que continúo revisitando. Ambos han trabajado el paisaje desde una perspectiva distinta. En fotografía, a nivel local, Andrea Ostera, una increíble fotógrafa rosarina y también docente que ha influido en mi mirada. Está también Gabriel Valansi y Jorge Macchi, he estudiado con ellos y los admiro mucho. Uno un tanto más obvio, pero que me encanta, es Magritte. Todos, son artistas que me hacen pensar mucho. Agregaría también a Vija Celmins, Rosângela Rennó y a Pierre Huyghe. También me inspiran mucho mis colegas más cercanos como ser Sofía Bohtlingk, Marcela Sinclair, Cecilia Szalkowicz, Nicolás Martella, Martín Sichettti, entre otros.

©Erica Bohm

¿Qué esperas lograr con tu trabajo fotográfico?

En relación a lo que puedo capturar, siempre me pareció interesante la fotografía y su relación con la realidad y la ficción. La fotografía es un recorte de momentos. Poder capturar una imagen a partir de un papel fotosensible es muy simple, y al mismo tiempo puede capturar la complejidad que se genera al pensar el paso del tiempo. La fotografia puede capturar, poéticamente, el pasar de miles de millones de años. Pensaba en todo lo que no se puede abarcar, el universo, todo el tiempo del universo; modestamente, ese era mi relato. No puedo capturar el universo, pero puedo fijar un instante de una noche que abarca toda la complejidad de ese tiempo y de todo lo que no se muestra en ese tiempo.

©Erica Bohm

Me interesan los formatos que utilizas. En Planet Stories utilizas las Instax para representar fotografías sobre astronomía de distintos institutos. Pensé mucho en la evidencia de reflejarnos en la sombra del astronauta como seres humanos. ¿Podrías hablar un poco sobre el uso de este formato?

Hace muchos años que me interesa la astronomía y la ciencia ficción. A partir de la apertura de bibliotecas digitales y el avance de la imagen digital, encontré el archivo completo de la misión Apollo. Por otro lado, en general, las imágenes producidas por los telescopios, son una construcción de apilado de muchas tomas fotográficas. Esa imagen producida no se puede ver a simple vista, con el ojo humano, ni a través de los telescopios. Eso a mí me parece maravilloso. La cámara fotográfica, que acumula luz, es ya una herramienta que supera al ojo humano; más allá de si es verdad lo que uno ve o no ve.

Siempre hay una duda en cuanto a la imagen, incluso mucho antes de la modificacion digital. Como si ver con nuestros propios ojos fuera una afirmacion de la realidad. Pensaba cómo poder traducir eso a un trabajo fotográfico, la presencia en ese territorio, con imagenes sacadas por astronautas o tomadas por sondas como la de Curiosity de Marte o la de Magellan en Venus. Fue entonces que decidí utilizar las Fujifilm Instax, que son como la Polaroid. ¿Qué mejor cámara para posicionarse en un espacio que esa? La misma cámara revela el objeto y no hace falta procesarla.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

Sé que te formaste como artista visual, como pintora. ¿Cuáles consideras que son tus herramientas de trabajo?

Son muchas, me parece muy interesante poder encontrar el soporte para albergar ideas. Las herramientas en mi trabajo varían mucho. En Moonlight, están las estenopéicas; pero además está un libro de conversaciones entre astronautas. Para este libro tomé las conversaciones transcriptas de la mision Apollo 11 producidas dentro de la cabina; velé muchos de los tecnicismos de la comunicación con la tierra y mantuve lo más subjetivo y lo más poético, entre ellos una conversación sobre el uso de la cámara fotográfica. Creo que cada trabajo tiene un display y una herramienta diferente para ser parte de mi producción y objeto del mundo, no dejan de ser objetos producidos. Una herramienta fundamental son las ideas y conocimientos que una puede tener, también está la astronomía y la inspiración literaria. Muchas de mis herramientas no son tangibles.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

Elena: Volviendo un poco sobre los materiales, las técnicas y el tiempo; existe una contradicción entre el tiempo que se refleja en las imágenes, el largo proceso de creación y conceptualización, y la herramienta técnica instantánea. Con herramientas sumamente sencillas nos invitas a ver mundos extraños. Además, no tienen un referente común y creo que aquello va en relación a la producción de la imagen. Me gustaría que pudieras ahondar en estos dos elementos.

En cuanto a la temporalidad de mi trabajo, depende del proyecto, unos toman 8 horas y otros 2 a 3 años. El proceso de realización de cristales es distinto a una estenopéica. A pesar de que la materialidad de los cristales no sea fotográfica, tienen como punto en común el tiempo que requiere su realización. Son experimentaciones que trabajan con el tiempo, que se nutren de la espera. A mí no me interesa lo inmediato, me interesan los procesos largos por mis inquietudes en relación al espacio y a la finitud misma de los seres humanos. El universo tiene miles de millones de años y existe ahí, algo que me reverbera mucho. Con El cristal perfecto intento replicar procesos geológicos de millones de años en uno o dos años. Es mi pequeño aporte en el tiempo, dentro de mi finitud, no sé cuantos podría hacer.

Elena: Me parece interesante este diálogo de narrativa visual que entablas entre ciencia ficción y poética. ¿De dónde surge la necesidad de conjugar estos mundos?

Me atrae mucho la poética de la ciencia, de universos paralelos y la posibilidad de viajar en el tiempo. Creo que es muy interesante pensar en las teorías en su forma más básica, la ciencia ficción y la literatura nos ayudan a entenderlas. Desde ese relato, me importaba generar imágenes en los espectadores. Una tercera imagen que se construye en la/el espectador/a. La/el espectador/a desde un lugar activo, no quiero perder el misterio. Quiero generar más preguntas que respuestas, cuando miro a las estrellas me hago preguntas todo el tiempo.

Incluso con respecto a la producción, se preguntarán cómo está hecho. ¿Sacó ella la foto? Así, se crean inquietudes como sujeto activo en la mirada. Por eso somos artistas, para generar preguntas en los demás.

©Erica Bohm

©Erica Bohm

¿Qué te inspira de América Latina?

Nuestro espíritu revolucionario para cuidar a nuestra Latinoamérica que está siendo tan apaleada por los incendios y las políticas patriarcales de potencias poderosas. Somos un lugar con muchos recursos naturales, de mucha pluralidad, de muchas voces. América Latina es una potencia muy fuerte, tenemos que estar los más unidos posibles para proteger nuestro territorio. Creo que eso es lo que ha mostrado la pandemia, debemos cuidarnos entre todos y producir localmente. Estar conectados con el mundo, pero no perder la idea de nuestra localidad, o sino vemos nuestro territorio extraído de manera ilimitada.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

Love and Loss in the Cosmos: Valeria Sestua In Conversation with Vicente IsaíasMarch 19th, 2024