Focus on Norway: Terje Abusdal | Slash & Burn

My initial introduction to Terje Abusdal came in a manner that has grown common in 2020, by means of a Zoom interview after having exchanged numerous emails. I was pleased to put a creator’s face to his starkly intriguing project Slash & Burn that focuses on a little -known ethnic minority in Norway, the Forest Finns. I was impressed with the ingenious efforts he took in his efforts to recreate symbolically and technically the fire and light of their working lives. Some of these efforts were accomplished with the use of light painting techniques in the remote forest border between Sweden and Norway on the night of a full moon to brilliantly illustrate their somewhat unique farming means and nomadic ways. Finally, I was also intrigued with his focus on photo books as a viable and productive avenue to promote his photographic work.

Terje Abusdal is a photographer and visual artist born in Norway with a Master of Science in Tourism & Environmental Economics from the University of the Balearic Islands, Spain and currently pursuing a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Bergen, Norway. His practice as a visual storyteller focuses upon the intersection between fact and fiction. In 2017, his story on the Forest Finns – Slash & Burn – won the Leica Oskar Barnack Award and Fotogalleriet’s Nordic Dummy Award. Slash & Burn was published in cooperation with Kehrer Verlag in 2018. He has also published the books Radius 500 Metres (2015) and Hope Blinds Reason (2019) by the publisher, Journal. His work was recently exhibited at Noplace and Henie Onstad in Oslo. IG: @terjeabusdal/

Slash and Burn

Finnskogen – directly translated as The Forest of the Finns – is a large, contiguous forest belt along the Norwegian-Swedish border, where farming families from Finland settled in the early 1600s. The immigrants – called Forest Finns – were slash-and-burn farmers. This ancient agricultural method yielded bountiful crops, but required large areas of land as the soil was quickly exhausted. Population growth eventually led to a scarcity of resources in their native Finland and, fuelled by famine and war, forced a wave of migration in search for new territories.

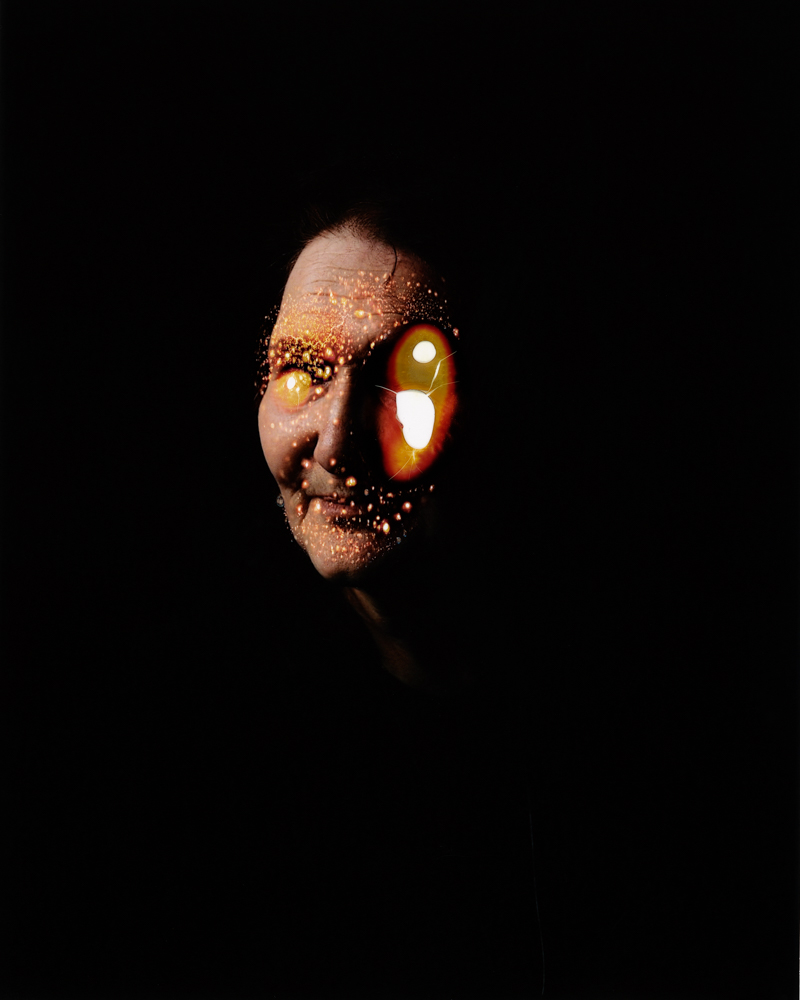

The Forest Finns’ understanding of nature was rooted in an eastern shamanistic tradition, and they are often associated with magic and mystery. Rituals, spells and symbols were used as a practical tool in daily life; that could heal and protect, or safeguard against evil.

This photographic project draws on these beliefs while investigating what it means to be a Forest Finn today, some 400 years and twelve generations later, in a time when the 17th-century way of life is long gone, and their language is no longer spoken.

Your project, “Slash and Burn” is a rather complex view of an unusual ethnic minority group in Norway. What was your initial impetus to pursue a project about the Forest Finns and how did it evolve over time?

I’m very curious about and interested in themes that have traces of the past, but at the same time have a contemporary social relevance. I was introduced to the Forest Finns by one of my former colleagues. She grew up there and helped me get started in terms of initial contacts. From there it just grew through word of mouth. In the sense that one encounter would lead me to the next. It is a very friendly place, so I had no trouble at all finding subjects who were willing to be photographed and speak about being Forest Finns.

The process of realizing the project has been organic, if you can use such a term in photography. From a quite straight documentary approach to start with, it slowly changed to include more conceptual methods such as staging and physical interventions in the photographs. The complete story also contains archival material sourced through extensive research. It is a mix of facts and fiction. As I learned more about the history of the Forest Finns, it became clear to me that I had to reinvent the past to tell this story. Because how can you photograph something as intangible as culture, especially when what defined it in the first place does not exist any more? So to be specific, I took certain elements of the past – fire, smoke and shamanism – and introduced them into the story.

The project has strong visual elements of magical realism and shamanistic touches. What inspired you to focus on these elements?

Finnskogen have always been associated with magic and mystery. And as I learned more about the Forest Finns, I became increasingly interested in the shamanistic understanding of nature they had brought with them from the east. The notion that all things, living and dead, possess a spirit, and therefore can be communicated with. I have tried to translate these elements of spirituality into my photographs, in an attempt to create a kind of Narnia, a magic world, in which the idea of the Forest Finns inhabits.

“Slash and Burn” also subtly addresses the current issue of migration and assimilation. How has the current political climate in Norway and Europe regarding refugees and migration influenced this aspect of your work, if at all?

I don’t consider Slash & Burn to be activistic work and it does not directly address the current political climate. But yes, of course, I am living in a society and therefore whatever I do in some way or another is influenced by the world around me.

In the Norwegian language, we have the terms 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation immigrants – but where does the line really go from being one thing to becoming something else? And is it blood that determines who we are, and if so, how much blood? Or is it a story about our common history?

And this is what the project – Slash & Burn – after slash and burn-farming is about. What does it mean to be a Forest Finn today – four hundred years and twelve generations later – at a time when the original way of life has long since disappeared and no one speaks the language anymore.

What was your process in executing this effort? How did you manage to engage with the Forest Finns in a meaningful manner? Your portraits convey an intimacy that does not normally happen by chance.

I started out in the small town of Svullrya, which is considered by many the ”capital” of the Finnskogen. It is also the place where the first Forest Finns settled in the early part of the 1600s. The culture is very much alive here and there is a strong sense of identity with their past. I concentrated mostly on the people who define themselves as Forest Finns and who live in and around this area.

Most of the images came about through of knocking on doors, or finding people I had read about in the local newspaper, or characters that I was told I should visit. It was not so difficult to find people willing to be photographed. Most Forest Finns today wear their heritage like a badge of honor and they love to talk about it. The portraits are very important in the series, because in the end, being a Forest Finn is more a state of mind rather than a set of defined characteristics.

Do you feel that your project conveys an environmental message given the slash and burn methods employed by the Forest Finns? If so, how do you convey it in the images?

The environmental aspect is not really a part of the project. Slash and burn farming were practised by Forest Finns in Norway until the early 1900s. Very sporadically though, since it had been forbidden by law since 1648. Today it would probably not make much sense to do it, since timber is much more valuable than eventual crops (also taking into account labour-cost).

I noticed that each of your projects has resulted in a photo book. How has this format for portraying your work evolved? What advice would you give other photographers contemplating this format?

I enjoy doing both exhibitions and books. The transitory nature of the exhibition. That you can incorporate the physical space into the story. It opens up a lot of possibilities for play. And the photobook because of its quality as a natural vessel for a narrative. I work mostly with storytelling, so in that sense the photobook is a perfect format. However, if one messes it up, there is no going back. You have to live with it. An exhibition is more forgiving in that sense.

If I can give an advice, it would be to take your time and not rush to publish. Do a lot of reading, experiment with techniques and gather material – even if some of it you probably won’t end up using. If it becomes overwhelming, don’t be afraid to reach out for help with making sense of it. There are a some websites now where you can book online appointments to get assistance with just that. And when you have a body of work which has reached critical mass, it helps a lot to participate in a photobook workshop where you make a dummy.

What’s next on your photographic journey?

I recently published the book Hope Blinds Reason by the Swedish publisher Journal. I was on the road photographing for the project from 2014 until 2016, followed by three years of trying to put the material together. It is a visual narrative from a series of journeys made in India along the river Ganga, from its source in the Himalayas to its delta in the Bay of Bengal. Since its publication I’ve taken some time off to reflect and proceed very, very slowly with two other projects that are in the making. I always work on several projects at the same time. So if I am stuck in one place, I can shift to another. Let the former rest in the subconscious for a while, until it is ready to come to the surface again. This method seems to have worked out ok so far. In terms of the specifics of the projects, I prefer not to talk about them right now since they are all in the early stages. To give a hint, one of them involves my grandfather and his travels in the 70s and 80s.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026