Alex Christopher Williams in conversation with Lauren Tate Baeza: Black, Like Paul

Photographer Alex Christopher Williams and the High Museum of Art, Fred and Rita Richman Curator of African Art Lauren Tate Baeza recently had a conversation about Williams’ project, Black, Like Paul. The work explores the “liminal space between race/ethnicity and identity”. The series is a personal exploration of self and personal histories, but also examines the larger conversation of race. Williams states, “I had to navigate blackness as a monolithic trope and push past the difficult history of how black bodies are typically represented in imagery. I had to push past poverty porn and showing black bodies as victims. So, there is a dialogue between giving folks the dignity to have their own agency within these spaces while also having a conversation with the past about what it is to be black in this country. Not that I speak on it with personal experience, but I can speak on it in an academic and photographic way which what the black and white color conversation is all about.”

Kris Graves Projects has recently published Black, Like Paul and the book is ready for pre-orders HERE.

Alex Christopher Williams is a photographer / curator and runs Minor League, an artists-run project space and publication in Atlanta, GA. He was born in Ohio and raised in the American South. He received his MFA in Photography from the University of Hartford and his BFA from Savannah College of Art and Design. He is currently a part-time Assistant Photography Professor at Kennesaw State University. His work has previously shown at Silver Eye, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, The Safe House Black History Museum, Wish Gallery, MINT, whitespec, Con Artist Collective, and C/O Berlin. He is collected at the High Museum, The Do Good Fund, Savannah College of Art and Design and in private collections. IG:@alexxphoto @minorleagueatl

Lauren Tate Baeza is the Fred and Rita Richman Curator of African Art at the High Museum of Art. She previously served as Director of Exhibitions at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, where she curated the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection and organized numerous temporary exhibits using the visual arts to engage social issues. Baeza writes, consults, and speaks on a range of cultural and sociopolitical topics related to Africa and the African diaspora. IG: @elletatebaeza

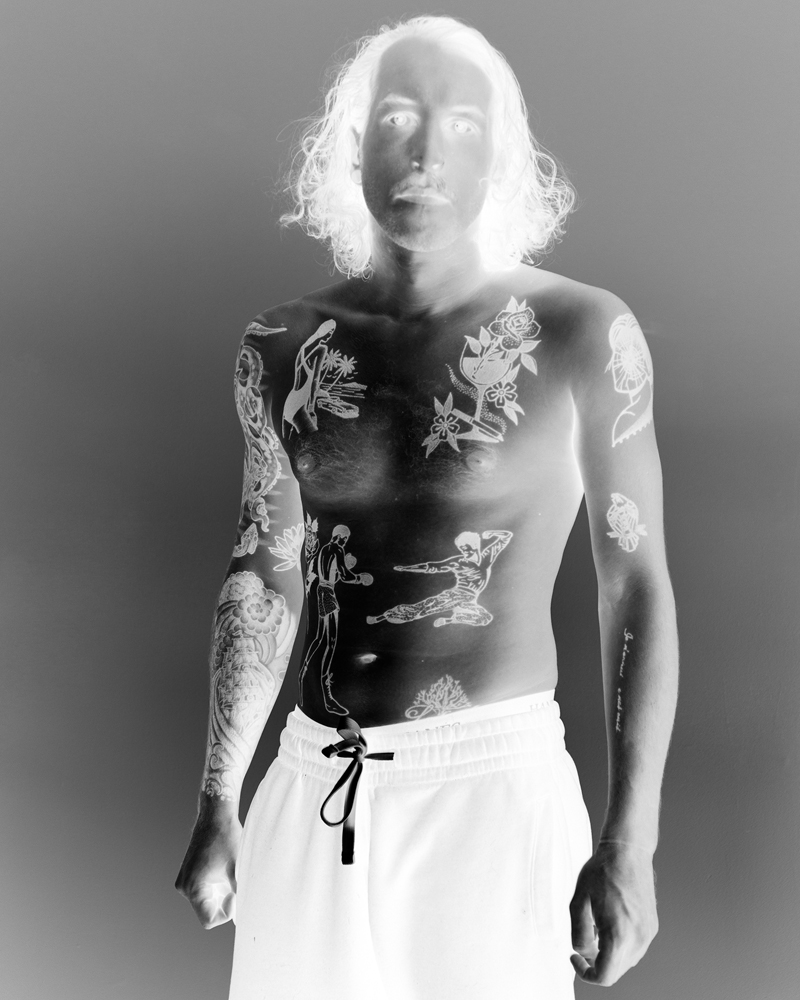

My work explores the relationship between historical, contemporary and personal experiences around issues of race, passing, and masculinity in America. I do this by focusing on male archetypes using folklore, legends, and icons as references to draw similarities between the past and present. As a white passing mixed race man, my photographic practice centers on the liminal space between race/ethnicity and identity. I use a view camera to make photographs in a documentary style while also attempting to actively subvert common tropes and traditions of the practice. – Alex Christopher Williams

Lauren Tate Baeza: Black, like Paul features images of creaks, churches, parks, fenced backyards, planed housing developments, street intersections, public basketball courts… Essentially, it appears to be a show the viewer can experience as a single community. Is this a single community or is it several different communities strung together?

Alex Christopher Williams: Yeah, I made these photographs all over the country but mostly in the south. Most of the photographs were made largely in historical black communities or in places that reflected the experience I had growing up in north east Ohio when I was a child. Although, in the book, I am not sure if I would say they appear as a single community or just the opposite, no one place in particular.

LTB: And so, they are strung together by the legacy black communities and or communities specific to your own story?

ACW: Yeah exactly. The underlying premise of this works is what is blackness and how I, someone white passing coming from a mixed-race background, am navigating my way to through this space. I didn’t grow up in a family with strong conviction to their identity. I am working my way through this space later in my life and I wanted to reflect the nuances of this conversation by photographing folks from different communities all over the country.

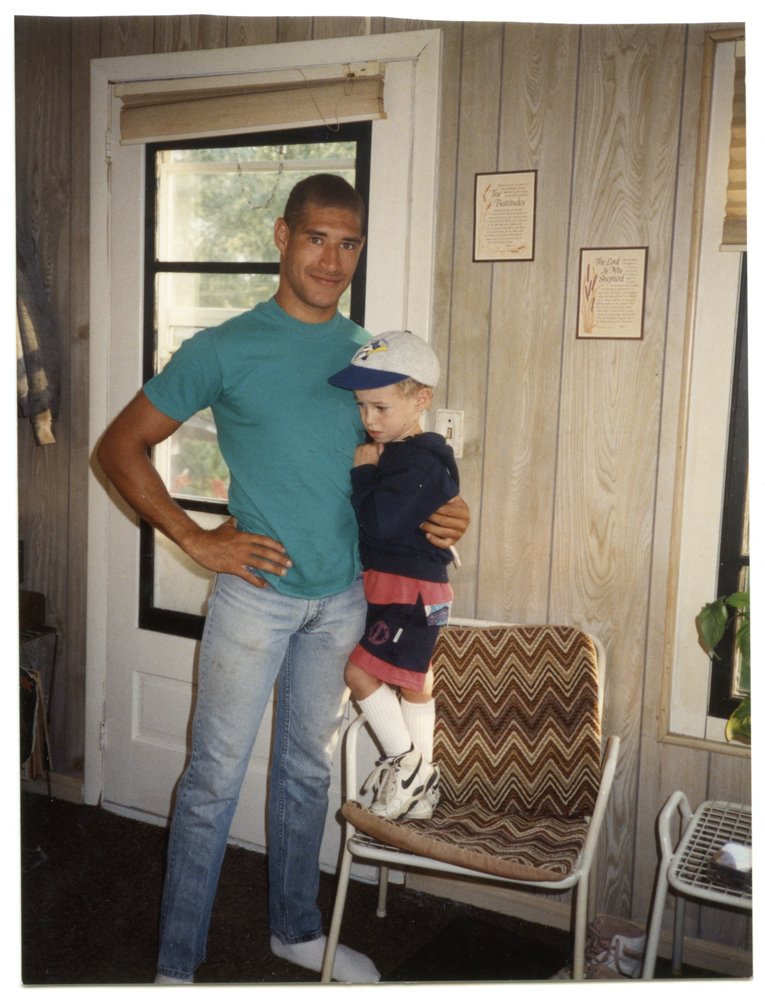

LTB: So, your work totes the line between fine art and documentary photography and as you mentioned, this series is beyond documentary and deeply autobiographical and personal for you. It’s an extension of a journey that you have been on internally, it seems. In fact, you have included some family photos that really drives the point home. Which aspects of your story are you engaging with this series? You mentioned that you’re navigating being a white passing person of a mixed background, what aspects of that identifying quality are you trying to uncover?

ACW: So, this project began by wanting to make pictures of my father, and having the distanced relationship that I have with him, it became too difficult a task because he still lives in Cleveland, OH. So, I had to figure out how to photograph that gap, not only physically but also emotionally. I started photographing men in my father’s likeness and thinking about masculinity, paternity but also vulnerability and the ways in which we manifest these ideas. I began with the photograph of a man drinking at a water fountain. I had a very deep conversation with him about why he was wearing a suit in the middle of August in Atlanta when the humidity was 94% and it was 100 ° outside. He told me this very impassioned story about taking his children to school. For him, it was important to teach them to have respect and dignity for themselves and by dressing with respect, it would demand that from others. He would put his suit on every morning and take his kids to school and then go to his construction job and change his clothes before going to work. He cared so much for his kids that I thought of him as an ultimate father figure. When I got the negatives back, I saw this power resonate even more because his face had been hidden in the shadows which allowed me to project “any man” into his silhouette. His image was made more complicated with its symbol of the water fountain and its close tie to the Jim Crow segregated south and I used this photograph as a roadmap for the rest of the project.

LTB: I love that. It seems like whether it’s an art project, academic research or a film, these things you set out with idea of what you were going to do… and it changes us. The journey to get this proposed outcome or to make this sort proposed argument ends up actually shifting and showing us to what it wants to be. I think that’s really interesting. You set out to document your father, but it ended up being a much more profound and contextually powerful story about your relationship with other men and masculinity and these broader themes all while staying very specific to your story.

ACW:I think of my practice as very improvisational where you put ingredients and it gives something back to you. It’s a ping pong relationship like that. I make myself available and vulnerable to getting curveballs and having to figure out how to respond to that. That’s ultimately why this project took so long to put it together because I had to communicate these difficult ideas in a very real and nuanced way without being didactic and too simple.

LTB: With its mix of family photos and current images, the complete Black, Like Paul series seems to be a dialogue between the past and present. Some of the community images documented are of older historic buildings or feature these generational traditions such as barber shop culture, trolley shop stations and these are juxtaposed with images of children at play and new cars and young boys wearing contemporary street fashion. The photos are also a mix between black and white and color. Are you intentionally creating a dialogue or even perhaps some tension between the past and present in this series?

ACW: Yeah, absolutely. The work definitely comments on current social and political struggles and it’s not so distanced relationship with our countries past. I made some the earliest pictures for this book after Trayvon Martin’s death and continued later after Eric Garner and Michael Brown were murdered by the police. Tamir Rice’s death hit the closest because I grew up in Cleveland hanging out in some of the same neighborhoods and I never witnessed such a crime. I used to do hood rat shit with my friends too but it was never in our wildest imaginations that a punishment could be so unjust. It’s stupid to state out loud but realizing privilege in this way is a difficult pill to swallow. My life could have been different had my genetics turned out to be a little bit differently.

Once I got past this point of obvious realization, I had to navigate blackness as a monolithic trope and push past the difficult history of how black bodies are typically represented in imagery. I had to push past poverty porn and showing black bodies as victims. So, there is a dialogue between giving folks the dignity to have their own agency within these spaces while also having a conversation with the past about what it is to be black in this country. Not that I speak on it with personal experience, but I can speak on it in an academic and photographic way which what the black and white color conversation is all about.

LTB: You do truthfully engage this with some gravity and sometimes of elements of feeling solemn, which is how I experience some of your photos but without perpetuating this idea of black victimhood. To your point, this trope of the ways that we are used to particularly black men pictured or painted is that they are on the receiving end of some violence or oppression. I think that you have all of the seriousness that that kind of trope is trying to engage without perpetuating it. There are really delicate depictions of the boys your photograph in particular that I think are counter to these hyper masculine images and that are also counter to them being victims of state violence. Again, which while we need to engage that, right. It has become repetitive and a bit reductive because black people are so much more than victims of white supremacy. In fact, showing them that way just centers white supremacy.

I have an aesthetic question. I find a lot of your images are off center and it gives me is a feeling of being kinetic, like you are moving past it. It makes me feel like I am there walking past the space. Was it purposeful to make it feel like I am moving in space instead of being an outsider?

ACW: That’s a really interesting observation but I am afraid not intentionally, at least not in the photograph. I am working with a view camera on a tripod which may be contributing to this master aesthetic that I struggle with. I would be quite bored with my work if everything was centered compositionally, so there’s that. I should say that the sequence for the book was labored over for years to create this push and pull dynamic conceptually in the book.

LTB: The photographs, as mentioned feature landscapes, communities, nature, but there’s also bodies featured in it. The images of boys resting and boys at play are some of the memorable images in the series for me. They’re seated on the ground or on chairs and they appear reflected and thoughtful sometimes looking directly into the camera. I think the reason I find these images moving has to do with what we already discussed. Black boys and girls often don’t get to enjoy full childhood at least in the eyes of state institutions, they become adults pretty quickly. Not that they personally become adults quickly, they are still children, but they are experienced as adults by outsiders a lot earlier than other people have to. They’re allowed to make mistakes, be silly, not worry about danger a lot longer than black children in this country. You capture the innocent of youth with these images and so it’s sort of a victory for me because so often were so used to seeing images of young black boys and girls having to be involved with one of these very narrow tropes. Seeing them in this innocence, almost looking like angels, is a joy because it is refreshing. But it also does feel a bit solemn, and this could be because of our time and the context of where we are, but I do get this sense there is a looming menace perhaps unseen in the photos. Why did you choose to photograph black boys and young black men in this way and how is it in dialogue with your broader thesis of being a white passing person of color in America?

ACW: Yeah well, I’ll say a lot of the photographs that I made in the beginning were of three brothers that lived across the street from me and so I had a much more personal relationship with them as subjects as well as neighbors. Radreikas mowed my lawn and I helped him work on his bike. We went through personal trauma together and I gave him rides to school when he missed the bus. Those photographs for them were photoshoots. They were a time to play like in a drama or theater act. It was a collaboration between the two of us. In those situations, I played less of the director and more of the observer. But I won’t deny your premise, these pictures are being made from the deeply rooted dark space. There is a lot of my own struggles reflected in these photographs as well as theirs because they live a tough life too. But for the other boys that I would meet on the playground or out in the world, 1/125th of a second is the amount of time it takes to make a picture that is powerful. Most often I find the pictures that are most powerful are the moments that we don’t expect. It’s the moment right before or after that I think works the best.

LTB: My last question is about your choice not to include text which I think for a photobook is actually not that rare but when you were touring this as an exhibition you also didn’t include any supplemental text. I know curators who come from an academic background have trouble a little bit and, of course, you know that. So, it occurred to me that you had been making a deliberate choice not to include text with the exhibition, except for the basic thesis which is a summary of 3-5 sentences. You aren’t giving a lot of context to groupings of photos or individual photos through writing. Could you talk about that choice that you’ve made to not include supplemental text to give more context to the work?

ACW: Yeah sure. I came to photography, really, through photobooks and at least early on I was never bothered to read the text at the front of the book. I thought that if an artist includes text in their own work, it must accompany the work conceptually in some way and therefore I decided to not do that. I didn’t want to encourage a didactic reading of the work which quite often I find these texts have the tendency to do. I sequenced this book very intentionally and I think all of the information needed is there, so I decided to rest on the laurels of the photographs. I believe that art is a visual language, no different than any other language, and that a viewer must exercise their visual literacy to read the work. As proved the massive misinformation campaign this country is currently enduring, I don’t think it’s a bad thing to encourage people to be more fluent with visual information. This is something we could all be better at.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026