Gina Osterloh

Gina Osterloh’s works provoke uncanny ripples in the visual languages, symbols, and cues that we often take for granted in an ever-accelerating, image-driven world. Through striking tableaus that collapse elements of spatial depth perception and figurative self-representation, Osterloh skillfully untethers us from traditional modes of seeing and perceiving. In doing so, the artist throws into question the embedded, habitual systems with which we identify and taxonomize the world around us. An interview with the artist follows.

Gina Osterloh‘s photography, video, performance art, and steel works with text expand upon issues inherent to photography. While the printed image comprises the majority of Osterloh’s oeuvre– her art practice activates photographic conditions including reproduction, replica, representation, flatness and volume, presence and absence, illusion and the Real. Symbolic themes and formal elements such as the void, orifice, and the grid, in addition to a heightened awareness of color and repetitive pattern appear throughout Osterloh’s works. Osterloh cites her experiences growing up as a mixed-race Filipina-German American in Ohio as formative interactions that led her to photography, larger questions of perception, and how a viewer perceives difference. Solo exhibitions and performances include Gina Osterloh at Higher Pictures Generation (NY), ZONES at Silverlens Galleries (Manila), and Shadow Woman as part of En Cuatro Patas at The Broad Museum (Los Angeles). Reviews of her work have been featured in The Brooklyn Rail, The New Yorker Magazine, Art in America, Art Asia Pacific, Artforum Critics Pick, Art Practical, and KCET Artbound Los Angeles. She is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art at The Ohio State University. Gina Osterloh’s work is represented by Silverlens Galleries (Manila) and Higher Pictures Generation (New York).

Artist Statement

My art is a continuation of more than 15 years of photo tableau, performance art, drawings for the camera, video, film, and recently, sculptural text works with steel. My experiences growing up mixed-race Asian American in Ohio were formative experiences that led me to photography and larger questions of how a viewer perceives difference. In many ways, my art embraces formal elements and abstraction to address the process of identification and how vision informs our understanding of identity.

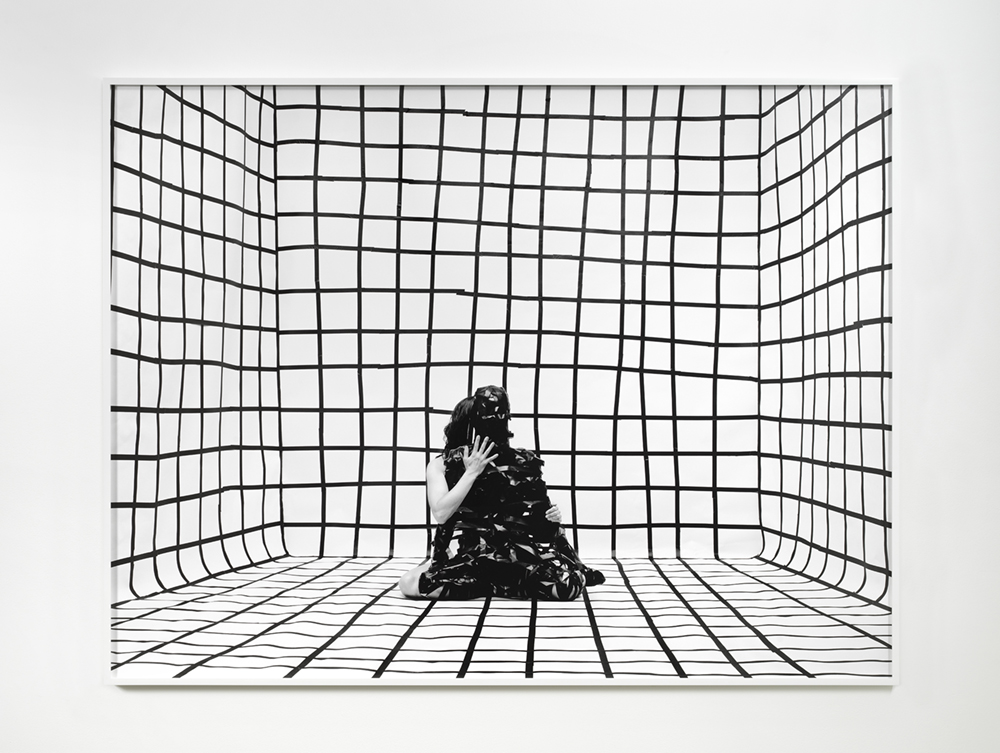

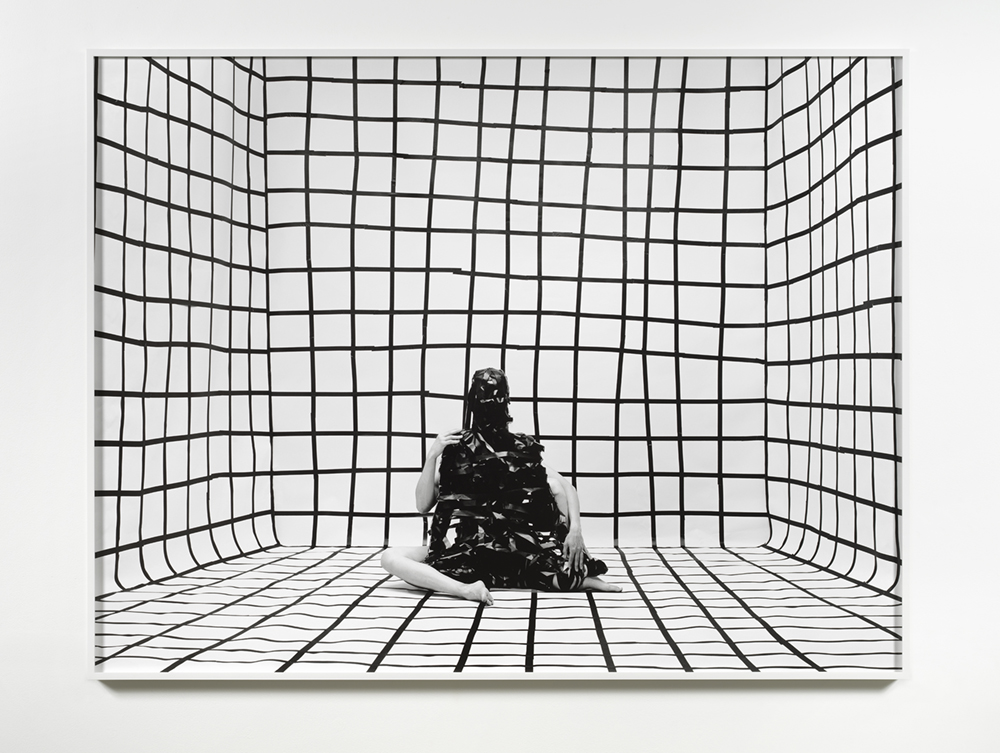

In 2017, I began to catalog symbolic themes that I use to address identity in my photographs. These visual schemata include hair, skin, eyes, and orifices, as well as structures such as the grid and basic units which contain “space” such as three walls and a floor, a room, or portal. The schemata became enlarged drawings on seamless backdrop paper that were photographed and printed at almost a 1:1 scale of 34.5” x 45.5” inches – an ongoing body of work titled ZONES.

Photographs titled Pressing Against Looking (2019-2020) depict long poles pressing against my eyes while sitting in a large-scale monochrome gray paper room. Pressing Against Looking activates a set of underlying philosophical questions: How can a woman press against the framing devices which attempt to fix her/their identity? How is looking a form of pleasure and pain, and how can I represent this in a visual image? Pressing Against Looking concentrates on the eyes and face, as zones holding a tremendous amount of pressure– the conceptual pressure of being compressed into the photographic frame– as the act of looking presses a body into a paradigm of social constructs such as race and gender.

Representation, reproduction, presence, absence, and erasure are wrapped in photographs such as Holding Zero (2020) in which black tape binds my body. I then present a reproduction of this mummified form, with my freed body holding the anonymous replica. In Grid, Eyes (2020) the figure is absent yet eyes at the crosshairs of gridlines peer back at the viewer. In Shutter Vision I activate operations of photography by holding the shutter release cable in my mouth and taking the photograph by closing my jaw, biting down with my teeth.

In 2019, I began working with steel for a body of work titled Pressure Plates that consider the simple etymology of the word “photograph” as “light-written” or “to record with light.” Each steel plate is sized to traditional photo dimensions of 14 x 11 inches. Words are formed with a welder’s torch, considering the act of writing with bright hot light on a metal plate akin to photographic processes, as well as the intersecting histories of steel and photography as structural, technical and cultural forces. —Gina Osterloh

While your art practice makes use of photography as a fundamental tool, your work also seems to critique the medium itself, bringing into question the authenticity of a camera lens’ perception and how it relates to what viewers see and recognize. How and why did you come to include photography in your practice? What do you see as the benefits and limitations of the medium?

I first came to photography in high school, taking snapshots at hip-hop concerts and in the mid to late 90s, took affordable photography courses at San Francisco City College at $13 a credit. But photography how I use it today didn’t start to crystallize until I was accepted to UC Irvine for the MFA in Studio Art program. This is where my awareness of photography’s powerful potential to address both a physical and psychological state of being, began with the series Somewhere Tropical, created in my 1st year at UC Irvine. In one of the photographs, I simply turned my head away from the camera. I wanted to see what it looks like to turn away, to refuse identification– and that’s when things got strange. I had the print on my studio wall and became enthralled and freaked out by the shape of the head of hair, an odd hole in the middle of the picture plane, a shape that was not quite human, sort of animal-like, and possibly vaginal. I ran with this “strangeness” of the blank for subsequent series such as Blank Athleticism and Press and Erase.

I love your question about the benefits and limitations of photography. I think as an artist the limitations produce tremendous benefits. In my own work, the confines of the frame produce infinite potential. But this is a learned skill, the basics of visual literacy. I also teach a broad range of university photography courses, and on day one of Intro to Photography, we talk about how billions of people have cell phone cameras but barely anyone is visually literate nor aware of the constructed nature of images and the power dynamics at play with basic technical aspects such as camera angle.

You also bring up the connections between the camera, the lens, and perception. The camera is a technical apparatus and conceptual framework that enlarges cultural and sometimes deeply personal issues. Since it is one of primary mediums of representation– if we were to draw a Venn diagram for photography, one circle is the actual event and the other circle the viewer– the latter comprising an unwieldly sphere of ideology and personal connotations, beliefs and filters ranging from political affiliations to emotion and influences such as what one ate or didn’t eat for breakfast. In this Venn diagram, I am particularly interested in the overlap of the two circles: how I can use technical sphere of photography – for example camera angle, clarity, lighting– to point at photographic space, a space which historically produces heteronormative binary way of seeing (think reclining nude female) to lay bare the construction of race and gender (which in the end, is an eerie and often erroneous space).

The visual subject of your work is often your own figure obscured. Do you consider your work to be a form of portraiture (and, more specifically, self-portraiture)?

I’d like to linger a bit with your prompt of the obscured figure. Your question points again to Somewhere Tropical, my first studio set construction and visual strategies of the blank that I continue today in photographs such as Holding Zero (2020).

How is the figure obscured – in localized areas such as the face, or the entire body – and what forces create a specific form or shape to obscure? Recently curator and gallerist Marina Chao wrote about my work as “denying legibility.” I love this, as here Marina points to the obscured figure as not only being “en contra” to misogyny and racism, or just a shape of refusal, but a generative and independent force. And it’s true, I see the obscured figures and shapes of refusal as portals of potential. I would say my photographs expand our notions of portraiture.

How does your work expand upon, push back against, and overall engage with the genre (portraiture) and its historical contexts?

Portraiture holds the expectation to identify and place the subject within the viewer’s understanding of race and gender, amongst other aspects of identity. It’s quite an automated and conjoined interpellation– the photograph asking the viewer to project preconceived notions of identity onto the subject, and the viewer projecting one’s beliefs onto the photographed body. I have been thinking of the physical and psychological sites of eyes, the face, and skin– in the reception and projection of identity constructs; the photographs Pressing Against Looking (2019) depict long black poles pressing against my eyes while sitting in a large-scale monochrome gray paper room. Part of my process involves a set of questions, in this case: How can a body press against the framing devices which attempt to fix their identity? How is looking a form of pleasure and pain, and how can I represent this in a visual image? What is the shape of vision?

I think it’s also important to note that I came to photography through performance art. (I was accepted to UC Irvine with performance video art.) The history of Performance Art and Conceptual Art, in particular from the late 60s and 70s when cameras both for video and photography became more affordable, and performance artists really started to shape and direct the backgrounds and environments for their work. They quickly realized their main audience was vis-à-vis the camera or image, as well as considering the potential of the set or series.

I am also deeply attracted to the overlap and intersections between Performance Art and Conceptual Art, in particular notions of the series or sets. While at first, they may seem disparate and far removed, I think of Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints-Face) 1972 and contemporary artist Charles Gaines’ Gridwork, from the 70s and 80s, but particularly his recent Gridwork such as Numbers and Faces: Multi-Racial/Ethnic Combinations Series 1.

My work is also influenced by the origins of photography– from the tracing of the silhouette to Imperialism and early colonial photography of the 19th century, a violent archive of erasure and Othering.

There is a distinctive, design-oriented eye for pattern and color behind your scenes. Will you tell us a bit more about the aesthetic choices in your constructed tableaus, and how these choices inform the messages you wish to convey?

I think of all the images we encounter every day and realize I must cut through ALL of that.

My first big jump with pattern and color started with the desire to create a symbiotic relationship between figure and space, to portray an equalizing force, as if figure and space could create each other. I think I was going for an out of body and equally embodied experience, at least the representation of this. In retrospect, I was creating my own context for being. Here again thinking of the series Blank Athleticism (2007), my first monochrome paper room with confetti and my body vomiting paper streamers.

Camouflage was one of the first visual strategies I employed to address simultaneous experiences of passing and not passing, a reality of mixed-race identity. I am also interested in color, pattern, and mimesis (the act of copying, as well as repetition) to bend and play with perception. Normative spatial relations inherent to photography such as foreground, middle ground, background –which locate and fix a subject in space– flicker and become unstable in photographs such as Anonymous Front (2010).

I remember Professor Simon Leung at UC Irvine saying in a committee meeting that camouflage splinters the visual field. A statement that I tucked in my visual strategy tool belt.

How do you relate to, and what do you make of, the identifier ‘Asian American’? What influences do you think your Asian American-ness—and other facets of your identity—have on your practice, if any?

Growing up in the Midwest, as a child and in high school, walking through the mall, there was often a question that was yelled out to me, “Hey what are you, are you white or black?” While this experience is not unique at all, it drove a spike and an acute awareness of Othering, and the erroneous and harmful nature of binary identity categories.

I do identify as Asian American, and also identify as mixed-race Filipino German American. Mixed-race Studies has been a helpful lens or reminder to resist all essentialized notions of race and identity.

In terms of my work– identity and the process of identification influences all of my work. Racialization, the process of projecting identity onto others, the role of vision and the perception of skin, influenced Obliterate (2019) and Shutter Vision (2020). Both photographs embrace the aspect ratio of traditional portraiture and use Old-master Rembrandt lighting. In each my torso, arms, and head are bound by black tape. Wanting to transfer the hierarchy of vision, in Shutter Vision I held the shutter release cable in my mouth and captured the image by closing my jaw, biting down with my teeth.

With this said, your questions remind me that it’s important to note my work is not literally about Asian American identity but takes on strategies that are formal, an embrace of abstraction to address racialization. I’m excited about so many artists today who use abstraction to address issues of identity, and writers and curators starting to support this discourse without essentializing the artist into just an identity show or just an abstraction show. The connections between abstraction and identity have always been there, and it’s something I’ve been committed to for quite some time.

As of late, there has been a marked increase in attention dedicated toward the AAPI community and our myriad experiences. How are you thinking and feeling about this shift in awareness? Does this trend have an impact on how you view yourself and your work?

Absolutely yes – our myriad of experiences. Can we please debunk the model minority myth and address that Asian Americans have the largest wealth gap within the racial group (see reporting from the Pew Research Center and the New York Times). The marked increase in attention is needed and doubly painful. Definitely not the same, but indeed related, thinking alongside Black Lives Matter – why has it taken this long? Of course I’m not surprised why. For artists I feel that our address or rewriting of what produces the monolithic falsehood and violent erasure is where our agency can be located. I’ve been reading Anne Anlin Cheng’s book Ornamentalism – and it’s haunting how she lays bare the connections between ornament, décor, technology, and the construction of yellow woman. What a frightening prospect with horrific implications. I can’t help but think psychologically plays a role in direct violence and microaggressions against Asians of all genders and sexualities. With Cheng’s writing that focuses on the production of yellow woman – whiteness renders the Asian woman as display, a disposable commodity or a technological specter (as in a video game or the film Ex Machina) that can be turned off and on, not fully human.

I don’t know if the current heightened attention toward the AAPI community drastically shifts my work, because I’ve been addressing the violence of erasure and issues of identity since the beginning. Clearly the attention toward the AAPI community is intertwined with the Covid-19 pandemic and a recent U.S. President who emboldened violence against Asian people. All of these forces that have been seething through the origins of our country, but tumultuously surfacing today, definitely influenced the creation of Mirror Woman, which was made in March 2020 at the beginning of the pandemic shutdowns in the States. The concepts of mirror and skin, or mirrored skin, have so many connotations to me, including being an armor of self-protection as well as how skin simply reflects the viewer’s notions of race, belonging, and citizenship.

What is something that has brought you joy over the past year?

Last Autumn 2020 (I’m still not sure how I pulled it off during the Covid-19 pandemic) I was absolutely thrilled to present a physical gallery exhibition with Higher Pictures Generation at their new location in Brooklyn. Gallery directors Kim Bourus, Marina Chao, and Janice Guy considered my work particularly because of my commitment to issues of identity, and saw my work complicating and refuting the model minority myth of Asian American identity. This year I also started working on a radio show “Voidwave” with bandmates Liz Roberts and Melissa Vogley Woods in which we feature non-binary and women sound artists. My 12 ½ year old dog Pepino brings me joy every day. I sing to Pepino spontaneously.

What are you looking forward to?

My next solo exhibition with Silverlens Galleries in Manila, Philippines! I also love water and am hoping to get to an ocean sooner than later.

Instagram: @ginaosterloh, @silverlensgalleries, @higherpicturesgeneration

Recent exhibitions:

Solo Exhibition with Higher Pictures Generation (Oct 10-December 12, 2020)

Group exhibition: Substrata, online virtual platform Epoch Gallery created and curated by Peter Wu, and Alice Konitz (January 9 – March 5, 2021)

Upcoming exhibitions:

Solo Exhibition with Silverlens Galleries November 2021

Solo Exhibition with Columbus Museum of Art, Autumn 2022 curated by Anna Lee, Ph.D.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026