Kristiana Chan

Kristiana Chan’s practice materializes the ways in which our complicated, historical entanglements with the landscape around us are woven into our present-day and future relationships with the environment. Integrating and transforming natural elements and processes into dream-like visuals, textures, and sounds, the artist’s works recognize the transcorporeal intricacies of a world with an abundance of (often dissonant) ecological narratives and responsibilities. An interview follows.

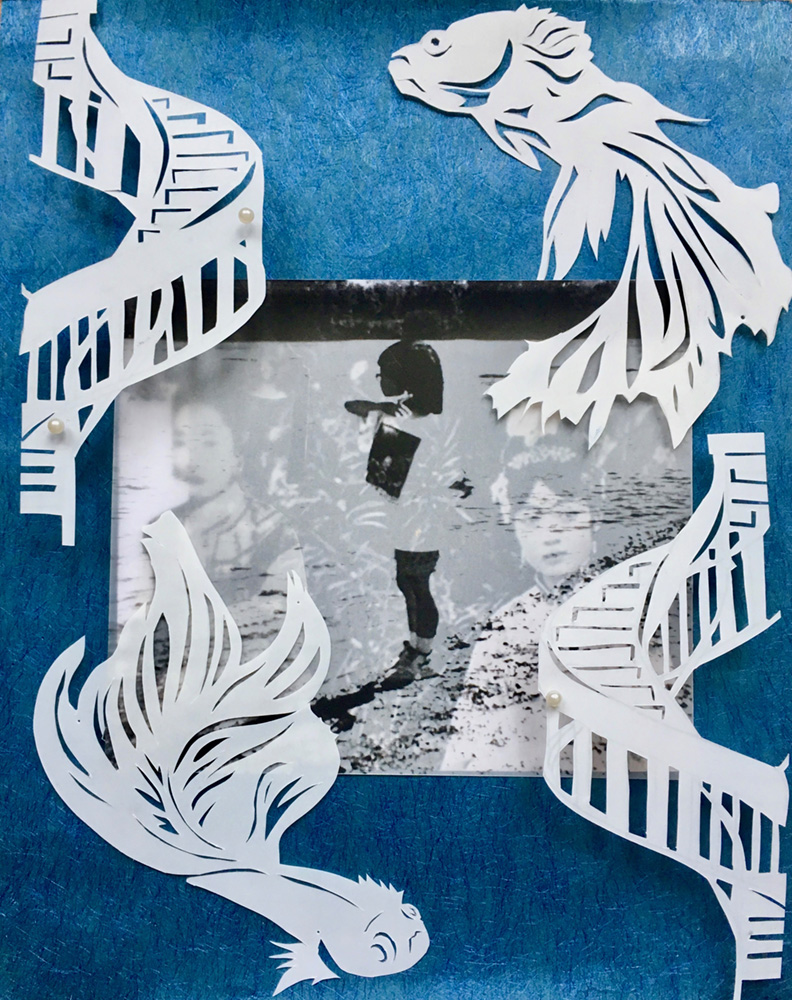

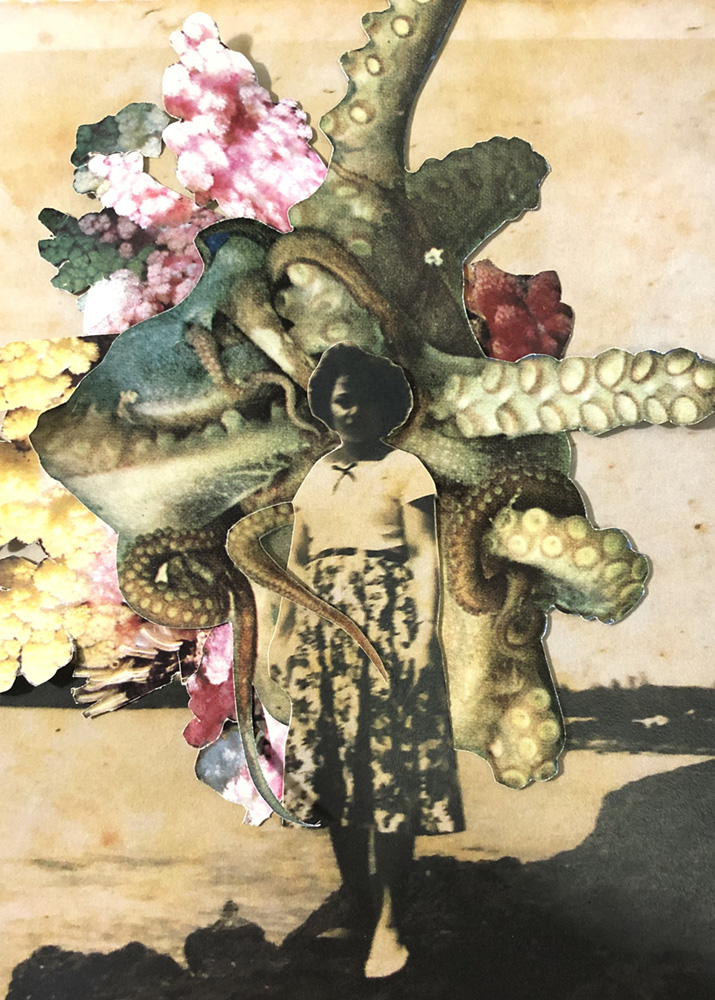

Kristiana Chan is a first generation Malaysian-Chinese artist, writer, and educator from the American South. Her work examines the intersection of ancestry, memory, and race. She researches the political, historical, and environmental heritage of the landscape and its material elements, and incorporates their environmental and elemental properties into her processes. Working across disciplines, she often use video projection, archival photography, sound collage, and cut paper in addition to experimental photographic chemical processes. She is a Teaching Artist Mentor with the Performing Arts Workshop, and a member of West Oakland based CTRL+SHFT Collective. She is a graduate of the New York Foundation of Arts Immigrant Artist program, and has curated with Kearny Street Workshop and the California Institute for Integral Studies. Kristiana is based in the Bay Area.

Artist Statement

What does the landscape record and remember? The landscape has been considered as a conquered, romanticized body, disregarded as an ancient witness to not just geologic but also historic record.

I am deeply fascinated by how the not so distant histories of racial exclusion, erasure, and extractive environmental capitalism lay the foundation for everyday, lived contemporary experiences and contribute to our concurrent crises of violent racism and climate disaster. I believe that many of our nation’s problems lie in the roots of our foundation and history. My work seeks to revive and reckon with lost histories and lives, and their implications on race and environment, so that by knowing where we come from, we can envision a new future for ourselves.

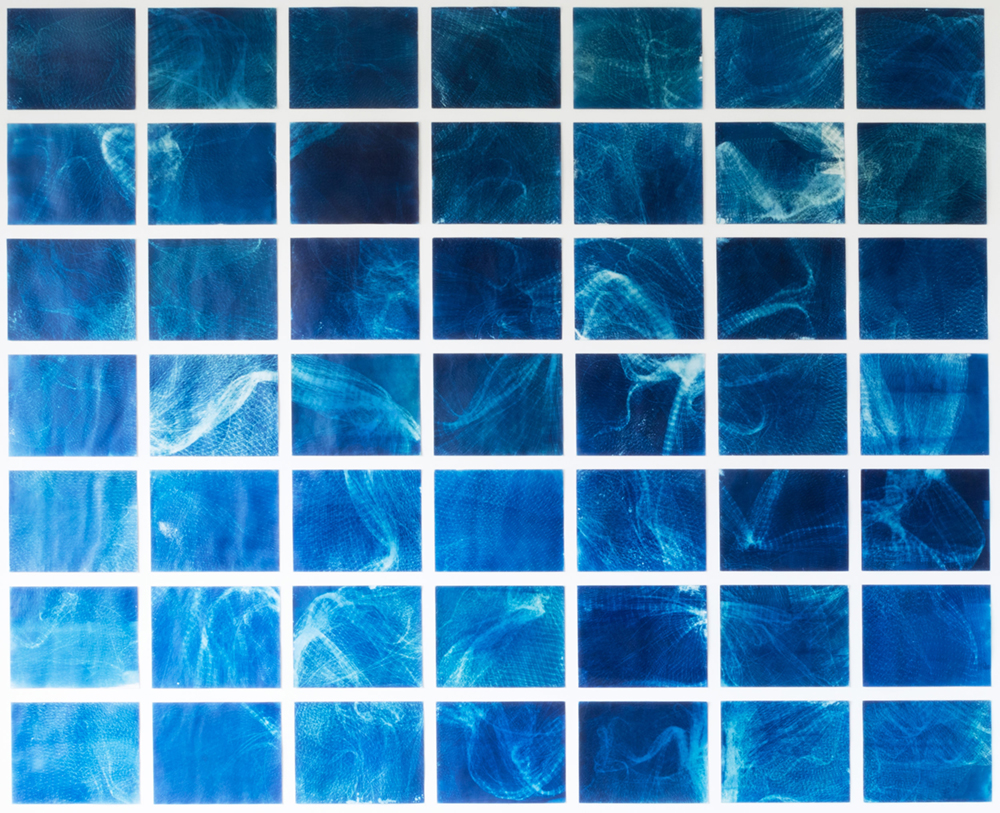

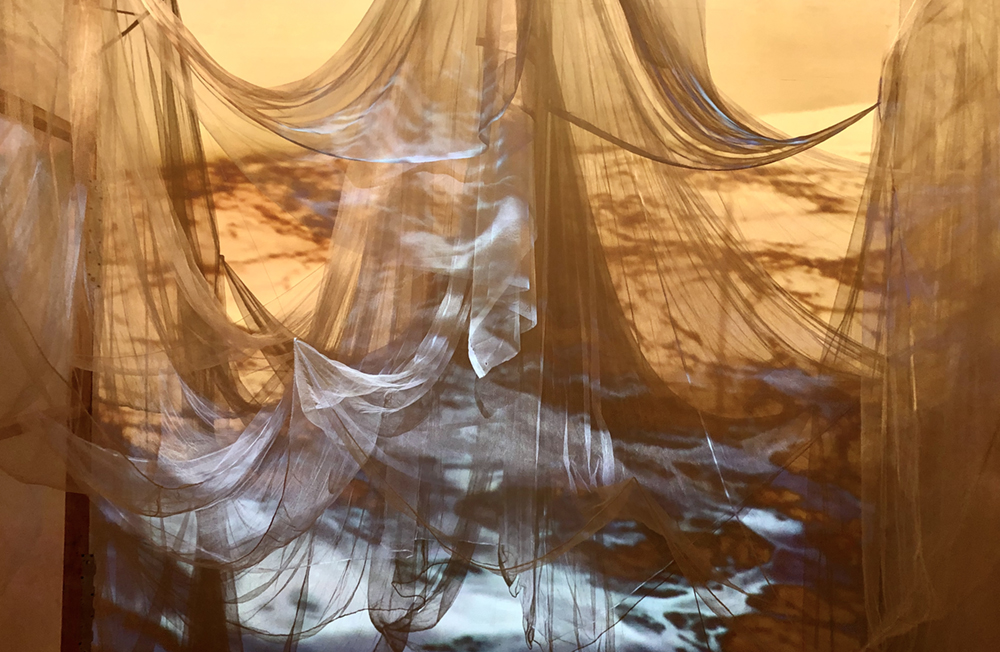

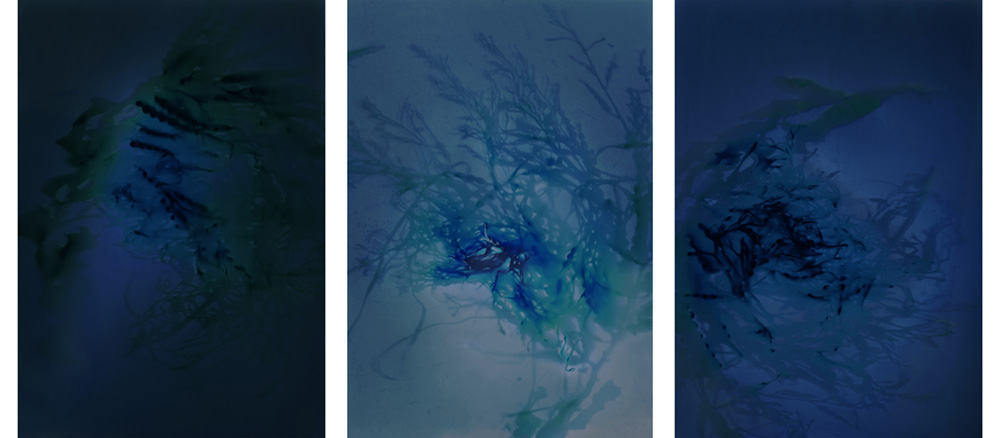

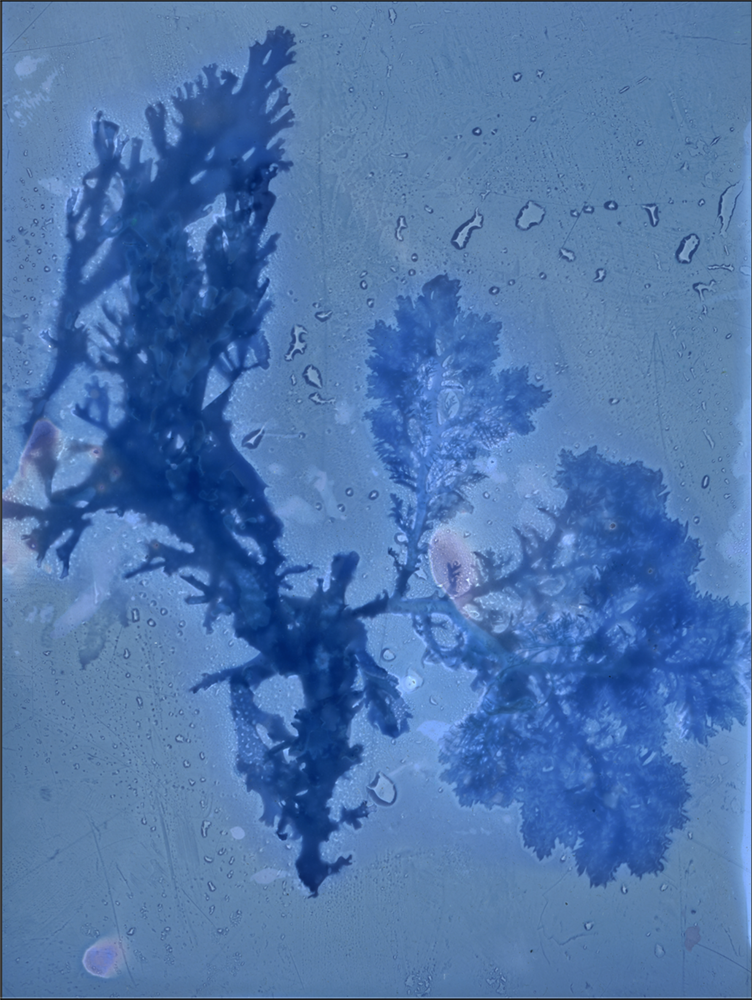

My work traverses the realms of memory, identity, dreams, and diasporic translocation. By investigating the landscape and the histories it has recorded, I hope to develop a language that can communicate between disparate worlds. I use cameraless photo methods that incorporate site-specific elements (seawater, salt, soil, clay) to document the living environment around me. I like to engage the elements of water, earth, fire and air as collaborators in my experimental processes to search for traces of the lost histories of forgotten ancestors. I’m interested in these alternative photography methods for how they not only capture the light of the landscape, but the physical matter and molecular memory of the materials that compose them as well.

Who was here before us?

What did they change? What did they take?

Who is benefiting from their labor, and who was erased?

Who are the ancestors, and who are the heirs?

—Kristiana Chan

How and why did you come to include photography in your practice?

I don’t know what originally drew me to photography, but I remember taking a History of Photography class in college and feeling like it was a language I understood. I taught myself how to shoot on a friend’s loaner camera, but later on became much more interested in the mechanical and chemical processes of photography. The slowness, deliberateness, and experimentation of the original photographic processes are like alchemical magic to me. It later became clearer to me that it was the material aspects and processes of photography that were important to my work, and I ditched most of my cameras all together. Most of my work now is done through contact printing, experimenting with different environmental and site specific emulsions, and sampling found and archival photographs.

One of the feelings I draw from your work is a sense of rhythmic, methodical layering—whether it be a layering of photographs, of textiles, of sound, of the movement of water coming and going. I’m wondering if you agree with this observation, and, if so, will you speak a bit more towards how you are using this layering technique and why?

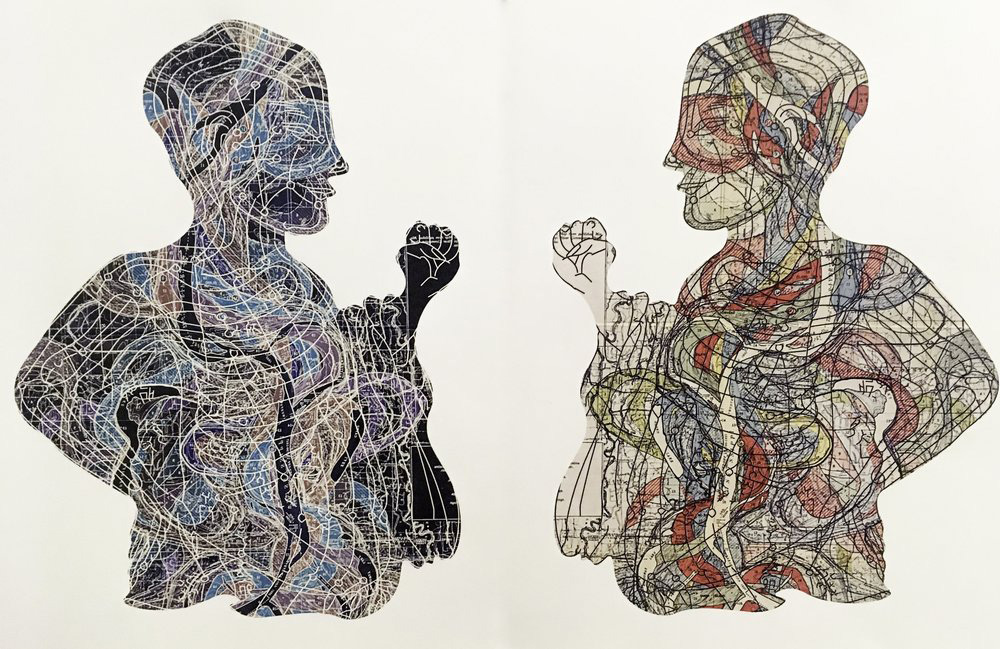

My work, no matter what medium, has always utilized lots of layering. I use it as a language to create a sense of the confusion, complexity, and disorientation of multiple realities and truths existing simultaneously. I like to think of my process as a process of untangling; I imagine myself following the loose threads of a tangled tapestry, teasing out the snarled stories and traumas of the past to find meaning in our collective histories and origins. Because a lot of these histories are lost, forgotten, or never recorded, I imagine my process as trying to remember a dream as it fades as you wake up–grasping at fleeting sensory details and finding meaning from disparate data.

There is an undercurrent of environmental consciousness and appreciation that bolsters much of your work as well. How has your relationship to the landscapes and waterscapes that you work within changed as you’ve progressed as an artist?

My instinct and inspiration to create draws greatly from the language of the landscape and the natural environment. Surfing and swimming are deeply important practices for me, and so the connection to the water has always felt innate. Connecting with the land, forests, and water has been an integral part of my spiritual and emotional healing. It is the way I connect to my own body, and to many unnamed ancestors. Their lives and stories have been forgotten and omitted by history, but they are preserved in the landscape where I can go to visit and commune with them.

How do you relate to, and what do you make of, the identifier ‘Asian American’? What influences do you think your Asian American-ness—alongside other facets of your identity—has on your art practice, if any?

I think the identifier “Asian-American” is a barely adequate moniker to represent the diversity of cultures and experiences of the diaspora. When you understand the political history of the term in this country, it makes more sense. I’m proud to claim my Asian-American identity, and maintain this as only one of my identifiers, but also understand that, as Cathy Park Hong says, the paint is still drying on the “Asian-American sign”. We simply haven’t had enough time as a unified body to develop what this name means, and remain splintered.

To me, being an Asian-American (noun) creating “Asian-American” (adjective) art means examining the stories we have inherited, sifting through the tangled narratives, untangling the knots, and reweaving the strands into a tapestry of resilience and justice. This means constantly relocating myself in a nation that does not know how to “place” me and my body, being displaced and dislocated within the racial binary, and triangulating between degrees of whiteness and otherness. It means being caught between a multitude of paradoxes (conspicuous, yet invisible; POC yet white adjacent model minority, privileged yet persecuted…) and learning to hold opposing ideas and experiences as true within the same space.

As of late, there has been a marked increase in attention dedicated toward the AAPI community and our myriad experiences. How are you thinking and feeling about this shift in awareness?

I’m horrified at the violence against the Asian communities, which has been targeting largely the elderly, poor, and femme. The most painful part though isn’t just the violence–it’s how the public has acted so surprised as if this is the first time something like this (racism against Asians) has happened. Even more so that the media denies “racial motivation” in many of these attacks, and that amnesiac masses have seemingly forgotten their initial outrage.

What is something that has brought you joy over the past year?

Surfing, being more in tune with nature and its rhythms, connecting with animals, and the simple pleasure of cooking and sharing a meal with loved ones in my home.

What are you looking forward to?

I’m looking forward to being able to see my family again this summer for the first time in a long time, and planning a warm water surf trip when it’s safe and responsible to do so again.

Currently showing: Sowing Agency at SOMArts (San Francisco), and Excuse Me Can I See Your ID, II at Vessel Gallery (Oakland)

Instagram: @kristi_chan

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025