Spirit: Focus on Indigenous Art, Artists and Issues at The Griffin Museum

Sometimes planting a seed turns into an unexpected garden of spectacular beauty and power. A year ago, I was watching one of my first pandemic ZOOM artist talks through the Los Angeles Center of Photography. One of the artists shared a body of work that was so well articulated and moving that I couldn’t get the photographs and words of Donna Garcia out of my mind. I eventually reached out to Donna to congratulate her but also planted the seed to see if she had any interest in creating a series of features on Indigenous photographic artists and issues for Lenscratch. Not only did she say yes, she brought so much more to the effort. The posts were featured in October of 2020, kicking off on Indigenous People’s Day. She also connected Lenscratch with the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta for a dual exhibition and artist talks with these powerful image makers. The Griffin Museum of Photography’s Executive Director and Curator Paula Tognarelli was also moved by the work and offered to exhibit it at the Griffin Museum of Photography. The exhibition opened on May 26th and will run through July 9, 2021. There will be a virtual reception on June 10, 2021 at 7 PM. at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Sometimes planting a seed turns into an unexpected garden of spectacular beauty and power. A year ago, I was watching one of my first pandemic ZOOM artist talks through the Los Angeles Center of Photography. One of the artists shared a body of work that was so well articulated and moving that I couldn’t get the photographs and words of Donna Garcia out of my mind. I eventually reached out to Donna to congratulate her but also planted the seed to see if she had any interest in creating a series of features on Indigenous photographic artists and issues for Lenscratch. Not only did she say yes, she brought so much more to the effort. The posts were featured in October of 2020, kicking off on Indigenous People’s Day. She also connected Lenscratch with the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta for a dual exhibition and artist talks with these powerful image makers. The Griffin Museum of Photography’s Executive Director and Curator Paula Tognarelli was also moved by the work and offered to exhibit it at the Griffin Museum of Photography. The exhibition opened on May 26th and will run through July 9, 2021. There will be a virtual reception on June 10, 2021 at 7 PM. at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

About Spirit: Focus on Indigenous Art, Artists and Issues: The scope of the work in this exhibition reflects the intricate nature of indigenous identity. Ten artists have created images that reveal expressions of pain, resiliency, resistance, healing, tradition, history and celebration.

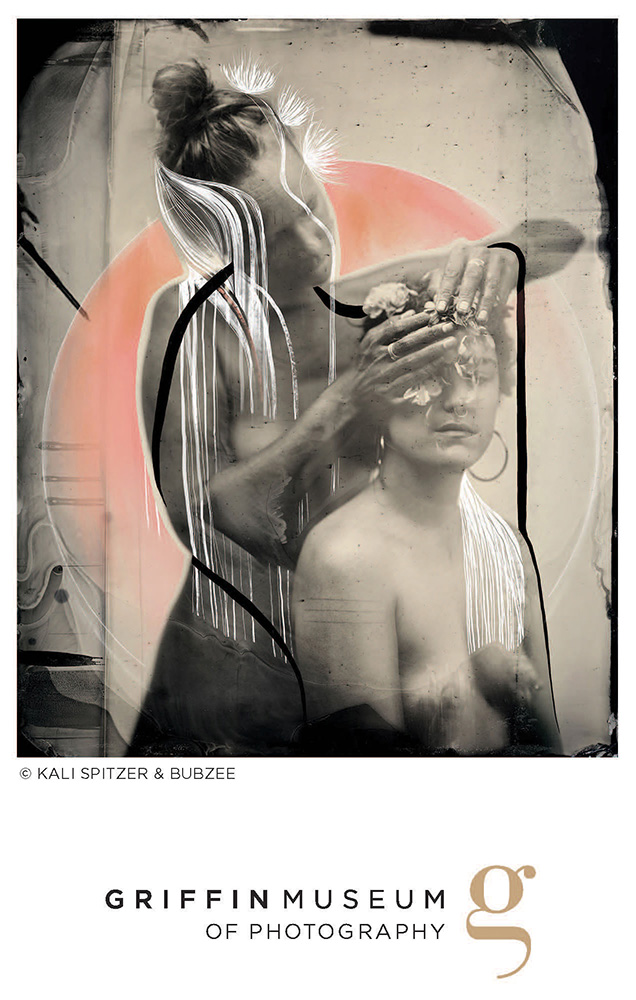

The exhibition includes NatGeo photographer, Kiliii Yuyan’s sweeping landscapes, internationally acclaimed artist Meryl McMaster’s dream-like self-portraits, Projects 2020 award recipient Donna Garcia’s historical recreations, and Sundance Film Festival invitee Shelley Niro’s work focused on women and indigenous sovereignty. Canadian documentarian Pat Kane, Fine Art photographer Will Wilson stunning panoramas and newcomers, Jeremy Dennis, the collaboration of Kali Spitzer & Bubzee and photojournalist Tonita Cervantes round out the show. Donna Garcia one of the exhibiting photographers has assembled and organized this exhibition. It has been featured on Lenscratch and highlighted at the National Center of Civil and Human Rights, in Atlanta Georgia prior to coming to the Griffin Museum Photography.

Spirit: Focus on Indigenous Art, Artists and Issues is an initiative designed to educate the public, through lens-based art, regarding the true history of indigenous people and recruit advocates for indigenous issues everywhere, but with a specific focus on the US and Canada, where native lands and people аre still coming under attack everyday

Curatorial Statement by Donna Garcia

In 2018, I created my series, Indian Land For Sale. I thought it would be a straightforward conceptual series based on the devastating consequences of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the histories that surround it. As I began my research, I discovered that there was literally no original documentation around this event. I went to local archives, museums, even the area where the Trail of Tears began in Georgia – nothing. I was frustrated, but I am not sure why I expected it to be different, because the ultimate goal of genocide is to wipe out all traces of a culture. That is when my project became about replacing what had been omitted from history.

Indian Land For Sale made me think deeply about the bias of history in North America. So when Aline Smithson asked me to host a week of Indigenous Art, Artists and Issues on LENSCRATCH, my goal was to feature a group of artists who represented a broad scope of lens-based perspectives, from icons to innovators.

As I recruited this amazing group of artists and curated their work, what struck me as strange, was that I hadn’t seen their work previously in my exploration of contemporary artists. Why had I not been introduced to the work of icons like Will Wilson or Shelley Niro? While all of the artists who will be featured/exhibited make work around indigenous issues, beyond that they need to be included in today’s photographic conversation, their work is compelling, distinctive, imaginative and impeccably executed. It’s important to know what the icons know, what the visionaries see, what the searchers have found and how the innovators create and how, as a collective, they will change the paradigm of history moving forward. You need to know these artists because their visual perspectives have the potential to reshape, retell, and rewrite the history of North America – now is the time.

Jeremy Dennis (b. 1990) is a contemporary fine art photographer and a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation. In his work, he explores indigenous identity, assimilation, and tradition.

Dennis was one of 10 recipients of a 2016 Dreamstarter Grant from the national non-profit organization Running Strong for American Indian Youth. He was awarded $10,000 to pursue his project, On This Site, which uses photography and an interactive online map to showcase culturally significant Native American sites on Long Island, a topic of special meaning for Dennis, who was raised on the Shinnecock Nation Reservation. He also created a book and exhibition from this project. Most recently, Dennis received the Creative Bursar Award from Getty Images in 2018 to continue his series Stories.

In 2013, Dennis began working on the series, Stories—Indigenous Oral Stories, Dreams and Myths. Inspired by North American indigenous stories, the artist staged supernatural images that transform these myths and legends to depictions of an actual experience in a photograph.

Residencies: North Mountain Residency, Shanghai, WV (2018), MDOC Storytellers’ Institute, Saratoga Springs, NY (2018). Eyes on Main Street Residency & Festival, Wilson, NC (2018), Watermill Center, Watermill, NY (2017) and the Vermont Studio Center hosted by the Harpo Foundation (2016).

He has been part of several group and solo exhibitions, including Stories, From Where We Came, The Department of Art Gallery, Stony Brook University (2018); Trees Also Speak, Amelie A. Wallace Gallery, SUNY College at Old Westbury, NY (2018); Nothing Happened Here, Flecker Gallery at Suffolk County Community College, Selden, NY (2018); On This Site: Indigenous People of Suffolk County, Suffolk County Historical Society, Riverhead, NY (2017); Pauppukkeewis, Zoller Gallery, State College, PA (2016); and Dreams, Tabler Gallery, Stony Brook, NY (2012).

Dennis holds an MFA from Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, and a BA in Studio Art from Stony Brook University, NY.

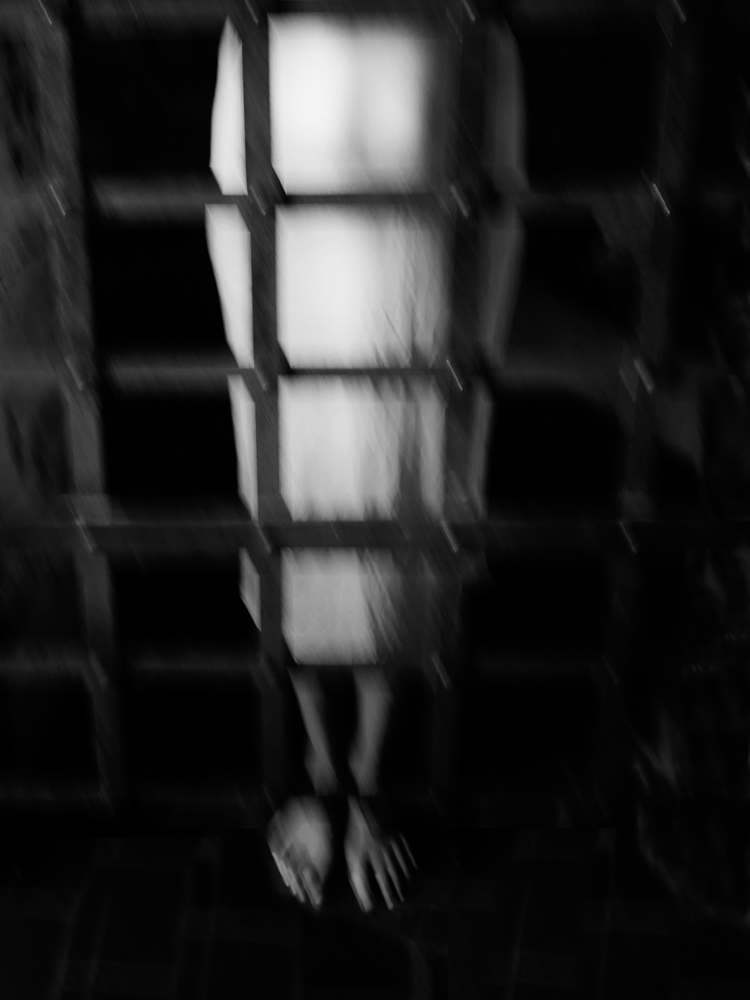

Nothing Happened Here

2016-2017

Nothing Happened Here is a photo series that explores the violence/non-violence of post-colonial Native American psychology.

Reflecting upon my own experience and observations in my community, the Shinnecock Reservation in Southampton, New York, specifically the burden of the loss of culture through assimilation, the omission of our history in school curriculum, and loss of land and economic disadvantage; this series illustrates the shared damaged enthusiasm of living on indigenous lands without rectification.

The arrows in each image act as a symbol of everlasting indigenous presence in each scene. The images may be as compelling if the subjects were of indigenous descent, but the decision to use non-native subjects reveals a shared burden. The question remains of how to overcome this troubled past. As we learn of early contact-period history between colonists and indigenous groups, that history sticks with us, and it is difficult not to link current predicament of power, gained or lost, with that important past.

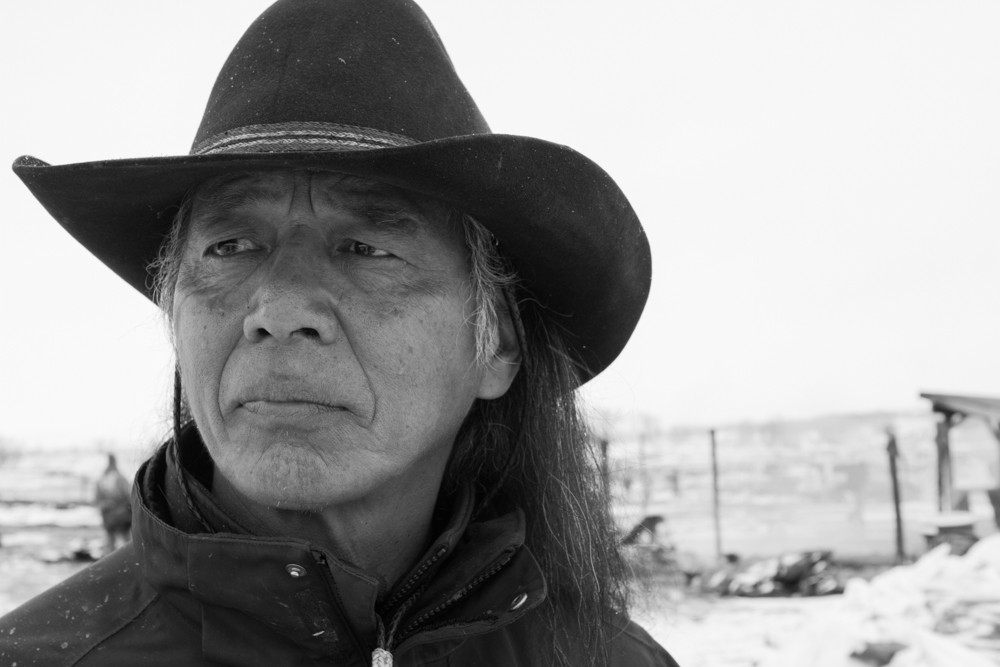

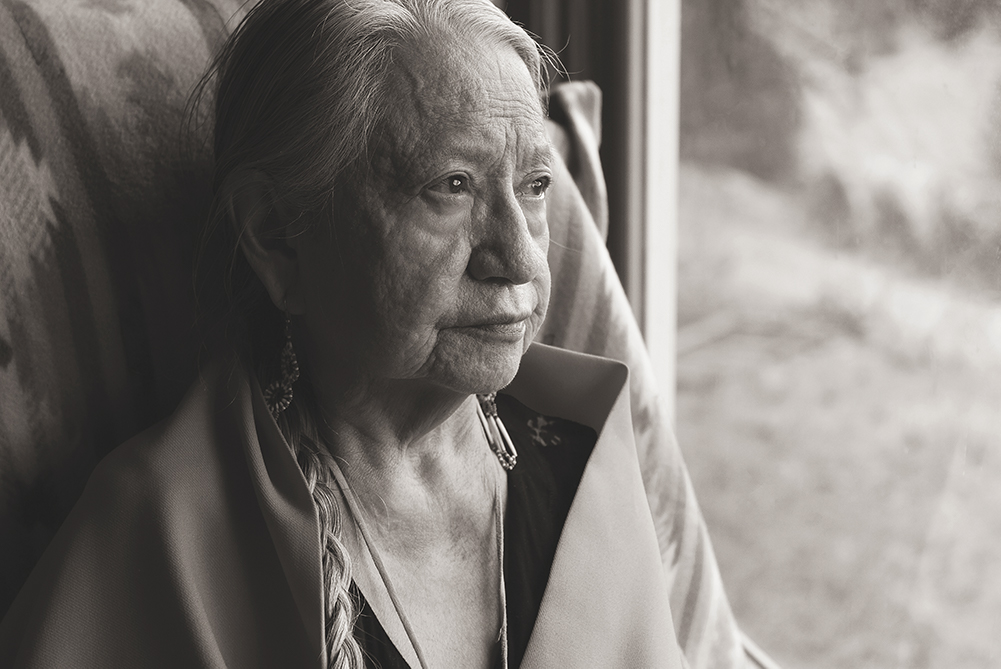

Tonita Cervantes: Standing Rock: Water Protectors

My work focuses on the common thread that binds people together: their humanity, and the dreams they have for a better life.

I am a boots-on-the-ground social documentary photojournalist. In my childhood, I was attracted to the underdog, the invisible — perhaps because of my own overwhelming feeling of not belonging.

After years of working in Hollywood as a Casting Director and feeling spiritually unfulfilled, I walked out of the studio and picked up a camera. It was time to tell the stories of people who don’t have a voice from their point of view, rather than casting for commercial advertising and consumer products that nobody needs.

I am fascinated by the resilience and community ties that are created out of a lack of resources. Witnessing the human spirit’s will to survive against all odds is humbling.

I am honored to have been an eyewitness to the historical and Indigenous-led movement that occurred on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota in 2016-2017. For six months I lived and documented the abuses of militarized state and federal law enforcement agencies committed against unarmed Water Protectors. I and many others, also tracked the infiltration of Tiger Swan, the private corporate militia hired to defend the Dakota Access Pipeline trenched across sacred treaty lands and under the Missouri River.

I interviewed elders and Water Protectors, and photographed head-to-head confrontations from the frontlines of the Standing Rock resistance.

My Standing Rock images are portraits of the descendants of great warriors, spiritual medicine men, keepers of the sacred fire and protectors of Mother Earth. The images of people like Lula Red Cloud, LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, and Ron His Horse Is Thunder are living proof that the legacy of their revered ancestors have prevailed and thrived despite an ungrateful nations attempts to rid them of their lands, their inherent Native rights, and their very existence.

Today the country feels like it is barreling at an accelerated pace in an unknown and dangerous direction; but prophecies from the ancestors encourage us to not give up, to have faith in the Creator, and to continue the fight for a sustainable future.

In 1877 Chief Crazy Horse of the Lakota people, a mystic and fierce warrior, had a vision:

“I see a time of seven generations, when all the colors of mankind will gather under the sacred tree of life and the whole earth will become one circle again.” – Crazy Horse

Ron His Horse is Thunder is the great-great grandson of One Bull, the nephew and adopted son of Sitting Bull, Chief of the Hunkpapa Lakota Nation. Ron His Horse Is Thunder is a licensed attorney and comes from a family that has a long tradition of fighting for social justice and civil rights. He has also been a champion of tribal sovereignty, especially in the realm of higher education. Besides serving as president of Sitting Bull College, he served as president of the American Indian College Fund.

“As the camps [at Standing Rock] grew, the media grew and got word out across the country. It showed that it is possible to create a coalition of people [that] when brought together could make a difference. And that was the biggest message.” “The camps at Standing Rock may be closed, but the movement that began there that united the tribes hasn’t died.”

This image was taken on February 22, 2017, hours before the Standing Rock prayer camps, located on sacred treaty lands, were brutally raided by state and federal agencies as well as Tiger Swan, a private corporate militia.

Chief Arvol Looking Horses was born on the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota. He is the recognized 19th-Generation Chief and Spiritual Leader of the Lakota people. He is the Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe. Chief Looking Horse is author of “White Buffalo Teachings,” and is a tireless advocate for maintaining the traditional and spiritual practices of this people’s ancestors. His prayers have opened numerous sessions of the United Nation.

“We warned that one day you would not be able to control what you have created. That day is here” Each of us is here in this time and place to decide the future of humankind.Did you think you were here for something else?”

This image was taken during the People’s Climate March in Washington DC.

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard is a historian and an activist. In April 2016, she was one of the founders of the Sacred Stone prayer camp that gave rise to the indigenous-led movement of resistance at Standing Rock. The aim was to halt the illegal construction of the poisonous black snake (the Dakota Access Pipeline) across sacred burial grounds on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. LaDonna’s people are Inhunktonwan from Cannon Ball, Hunkpapa and Lakota Blackfoot. Currently she is fighting for her life from brain cancer that may have been caused from the governments’ spraying of the camps with rozol, a toxic prairie dog pesticide.

153 years ago, her great-great-grandmother Nape Hote Win (Mary Big Moccasin) survived the bloodiest conflict between the Sioux Nations and the US Army ever on North Dakota soil. An estimated 300 to 400 of her people were killed in the Inyan Ska (Whitestone) Massacre, as many or more than at Wounded Knee in 1890. “We cannot forget our stories of survival.”

This image was taken at the Cheyenne River Camp after all other camps had been raided and closed.

Lula Red Cloud is Oglala Lakota from the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. She is the great-great granddaughter of Chief Red Cloud, primary signer on the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 that established the Standing Rock Reservation. She is a revered and beloved tribal member of the Lakota people. She is known as a prolific star quilt maker whose creations have been on exhibit at the Smithsonian as well as several

other museums throughout the country. She linked the historical similarities between the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre and the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, to the violent siege at Standing Rock driven by corporate greed.

Witnessing Water Protectors being beaten and abused, Lula Red Cloud said, “We were forced to accept the governments decision with a gun pointed to our heads. We could either leave camp or be murdered by the real terrorists–the government.”

This image was taken in her home in March 2017, a few weeks following the raid of the prayer camps at Standing Rock.

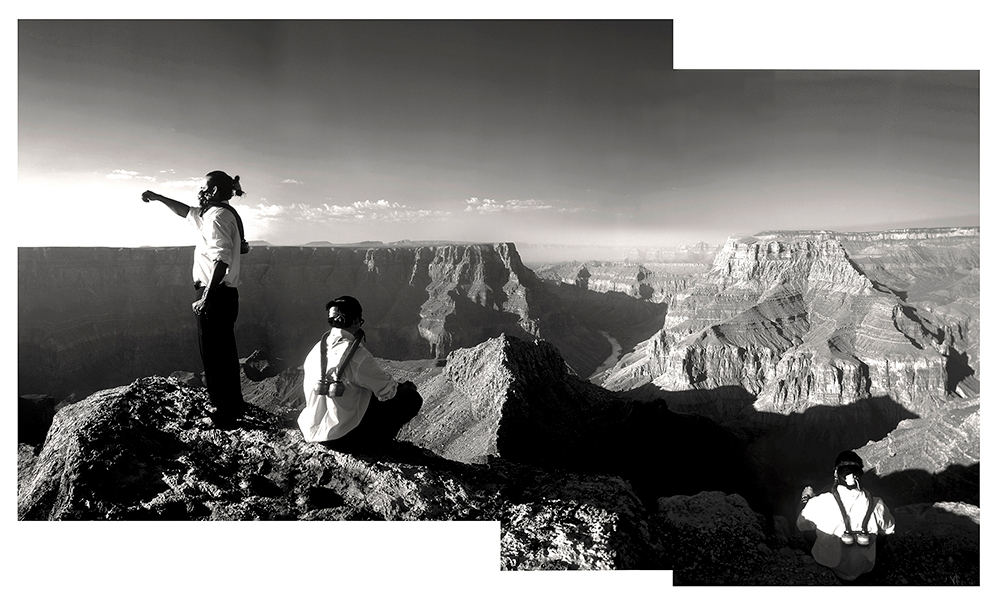

Will Wilson: Auto Immune Response (AIR)

Photographer and installation artist, Will Wilson (Diné/Bilagaana) creates a deliberate counter narrative to the romantic visions of Indigenous people living in an unchanging past. Though born in San Francisco, he draws inspiration from the many years he spent living on the Navajo Reservation as a child.

Wilson creates tension in his photography and installations, as the artist believes that Indigenous people remain responsible for protecting the environment and its future for all species. This story underlies the “quixotic relationship between a post-apocalyptic Diné (Navajo) man and the devastatingly beautiful, but toxic environment he inhabits.” This setting includes familiar symbols of cultural persistence, such as a Hogan (a traditional Navajo dwelling), coexisting with computers, wires, and futuristic furnishings.

Wilson describes AIR (Auto Immune Response) as a dialogue with “a post-apocalyptic Navajo man’s journey through an uninhabited landscape.” The artist’s use of self-portraits as the main character searching for answers about survival: “Where has everyone gone? What has occurred to transform the familiar and strange landscape that he wanders? Why has the land become toxic to him? How will he respond, survive, reconnect to the earth?”

For native tribes like the Diné, “toxic environment” encompasses not only the physical environment (the much larger Navajo Homeland, Dinétah, which was mined heavily for Uranium throughout the 20th Century), but also a historical environment of colonial resource extraction, arbitrary borders, and Federal Indian Policy which sought to “civilize the Indian” on reservations, for the more lucrative purpose of a land grab, for either mineral resources or agriculture. Wilson’s character resists arbitrary borders by existing in both, and yet his ever-present gas mask demonstrates that environmental contamination also ignores arbitrary borders. The result of this has been increased cases of cancer and autoimmune diseases among the people inhabiting these areas, destruction of ancestral land, and a continued history of “slow violence” against indigenous people.

Even though Wilson started this work in 2004, what is interesting to me is that it is more relevant than ever in 2020. As the world currently fights the devastating effects of climate change, and tries to push back on government’s irresponsibility around the decimation of our planet for profit, AIR reflects how native people have been fighting this for over a CENTURY.

Although this work focus’s on complex social and environmental issues, the result is a collection of dreamy yet powerful photomontages, in which the main subject merges with his environment creating poetic images that reflect dissolved states of time and space. The performative power of this work lies in the use of photography as an action for expressing feeling, not just for documentation.

Meryl McMaster earned her BFA in Photography from the Ontario College of Art and Design University (2010) and is currently based in Ottawa, Canada. McMaster’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Canada House, London (2020), Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (2019), Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto (2019), Glenbow, Calgary (2019), The Room, St. John’s (2018) Momenta Biennale, Montreal (2017), Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe (2015), and Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, New York (2015), amongst others. From 2016-2020 her solo exhibition Confluence travelled to nine cities in Canada, including stops at the Richmond Art Gallery (2017), Thunder Bay Art Gallery, Thunder Bay (2017), University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, Lethbridge (2018), and The Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery, Sarnia (2020). Her work has also appeared in group exhibitions at Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa (2020), Australian Centre for Photography, Australia (2019), National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2018), Ottawa Art Gallery (2018, 2019), Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery (2016, 2019), the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (2019), Plug In Institute for Contemporary Art, Winnipeg (2017), and Art Gallery of Guelph (2017), amongst others. She was longlisted for the 2016 Sobey Art Award and is the recipient of numerous awards including the Scotiabank New Generation Photography Award, REVEAL Indigenous Art Award, Charles Pachter Prize for Emerging Artists, Canon Canada Prize, Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship and OCAD U Medal. Her work has been collected by significant Canadian institutions, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Montreal Museum of Fine Art; and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

As Immense as the Sky

Meryl McMaster uses photography to explore identity and its distinct cultural narratives within lush, spectacular natural landscapes that evoke ancient folklore and myth with extraordinary visual impact. Her cinematic style connects still life, sculpture, narrative and performance. Meryl draws on her own mixed heritage, her mother being of British/Dutch ancestry and her father a Plains Cree native, to explore important themes and issues of representation.

Creating symbolic, sculptural garments and props, McMaster assumes diverse personas, such as a dream catcher or wanderer, often transforming herself into hybrid animal-human creatures. Her performative self-portraits present themes around memory and self, which are both actual and imaginative, and allow the viewer into the realms of her ancestors. Each tableau contains references to a multitude of stories and traditions from diverse Indigenous communities. These scenes often recall the Romantic tradition of the solitary figure in nature from traditional literature and painting.

Through the process of self-portraiture, McMaster also embodies the “shifts” of her subjects depending on the natural environment and the costumes. She does not do public performances. In one solitary moment, she creates a story, which may look like its part of a film, part of a dream sequence, a storybook or recounting history. She describes her pictures as “private performances that are responding to memory and to emotion in different ways.”

These captivating images аre captured across ancestral sites in Saskatchewan, where Meryl father’s ancestors are from as members of the Red Pheasant First Nation, and have lived for many hundreds of years, and the area is very significant to her family. Also, early settlements in Ontario and Newfoundland, where the artist interprets, and re- stages collected patrimonial stories from relatives and community knowledge keepers.

Acknowledging the personal and social history and effects of colonization, McMaster contemplates how ancestral stories are imprinted into the landscape by the people who once lived there, as well as those who still reside there. Meryl states, “These are very powerful, overwhelming places, with all kinds of history buried within these landforms that predates human existence.”

McMaster presents herself in nature, viewing the environment and seasons as an integral part of the cultural context while addressing the environmental consequences of colonization. She warns of the dangers of unsustainable land usage and the eradication of key species within ancestral ecosystems.

Photographer Kiliii Yuyan illuminates stories of the Arctic and human communities connected to the land. Informed by ancestry that is both Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous) and Chinese-American, he explores the human relationship to the natural world from different cultural perspectives. Kiliii is an award-winning contributor to National Geographic Magazine and other major publications.

Both survival skills and empathy have been critical for Kiliii’s projects in extreme environments and cultures outside his own. On assignment, he has fled collapsing sea ice, weathered botulism from fermented whale blood, and found kinship at the edges of the world. In addition, Kiliii builds traditional kayaks and contributes to the revitalization of Northern Indigenous/East Asian culture.

Kiliii is one of PDN’s 30 Photographers (2019), a National Geographic Explorer, and a member of Indigenous Photograph and Diversify Photo. His work has been exhibited worldwide and received some of photography’s top honors. Kiliii’s public talks inspire others about photographic storytelling, Indigenous perspectives and relationship to land. Kiliii is based out of traditional Duwamish lands (Seattle), but can be found across the circumpolar Arctic much of the year.

©Kiliii Yuyan, AB wears his hope mask in the art classroom at the Gambell School. April 12, 2018, Gambell, AK.

Masks of Grief and Joy

Photographer Kiliii Yuyan illuminates the hidden stories of Polar Regions, wilderness and Indigenous communities. Informed by ancestry that is both Nanai/Hèzhé (Siberian Native) and Chinese-American, he explores the human relationship to the natural world from different cultural perspectives.

In his series Masks of Grief and Joy, Yuyan takes the viewer to Gambell, located on the northwest cape of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, about 200 miles southwest of Nome and just 36 miles from the Chukchi Peninsula in the Russian Far East.

Death is not uncommon here on Alaska’s Saint Lawrence Island, whose population is entirely Siberian Yup’ik. The people of Saint Lawrence Island have been ravaged by colonization. In the 1800s American commercial whalers brought disease epidemics, followed by the 1900s when children were forced to leave their parents and attend boarding schools. An entire generation was subjected to the physical/sexual abuse and cultural genocide of those schools. The ensuing trauma has led Alaska Natives to the highest rate of youth suicide in the world – 13 times higher than that of American youth overall.

©Kiliii Yuyan, Reflecting on the grief in his life from losing a good friend to suicide, BK removes his grief mask to breathe easier. April 13, 2018, Gambell, AK.

Lens-based artist and documentarian Kiliii Yuyan shares the story of Molly:

Molly comes running up to me, snow crunching under her feet as she giggles and tries to catch her breath. The two of us are standing in moonlit snow on an island in the middle of the Bering Sea. It’s Molly’s home. We joke around for a few minutes when she suddenly bursts into nostalgia about her best friend Robert.

Robert’s dad used to push the kids around the house in suitcases. They’d stare at each other and burst into laughter. As Molly tells me this childhood story, her eyes begin to glisten. She tells me Robert’s father was like a surrogate dad. They would go out on the land for weeks. He’d never let anybody in the village pick on her. The three of them were inseparable.

But then she pauses, and after a long while, she tells me in a faltering voice that Robert had killed himself, and his dad had died from a heart attack shortly after.

©Kiliii Yuyan, LA reflects on family and loss at home in her mask of grief. Though her family has more than most, she is not insulated from the near-constant stream of deaths in the community, from cancer to suicide. April 12, 2018, Gambell, AK.

When Yuyan arrived in Gambell, one of the island’s two communities in 2018 with about 700 residents, he took on the task of creating a suicide-prevention program, in collaboration with the art teacher and staff at the Gambell school, as a form of art therapy for the students. One of the first activities was for the student to create papier-mâché masks. Arctic Indigenous cultures such as the Yup’ik are famously laconic, so this mask-making activity was designed as a socially acceptable way for teenagers to work through suppressed emotions. He asked the students to work on two masks: one representing their internal grief, the other representing their joy. He worked with his students for three weeks, taking cues from both traditional Yup’ik masks and references to pop culture.

The artist’s made portraits of the students wearing their masks in places that brought them closer to their grief and their joys. For grief, several students led him outside. He went to a basketball court, a reminder of a well-loved fellow student and basketball player who they said had recently committed suicide. Standing in that place, Yuyan could feel the pain carried by the students, as well as their fortitude in facing it. Most of the students wore their grief mask outside and their joy mask inside the comfort of their home.

During their time together, the students reflected on suicide in their community and how it had affected them. It was clear that it affected just about everyone, but there were also deaths from cancer and accidents as well. Despite all of the tragic losses, most of the students seemed to have a healthy approach to life. Their strength stands proves that despite centuries of ongoing trauma, Indigenous communities will continue to heal with each generation by learning to believe in themselves and preparing a way for their communities into a new era.

When one looks at these images what is apparent is the resilience of the individuals who аre wearing them and the compassion with which the pictures are made. As the world struggles in 2020 to find even a shred of empathy or humanity, both are found here.

©Kiliii Yuyan, MB wears her mask of grief a few steps from family’s front door. She lost her father to suicide last year, yet upon meeting in person, her resilience is evident in her energy and vibrance. April 12, 2018, Gambell, AK.

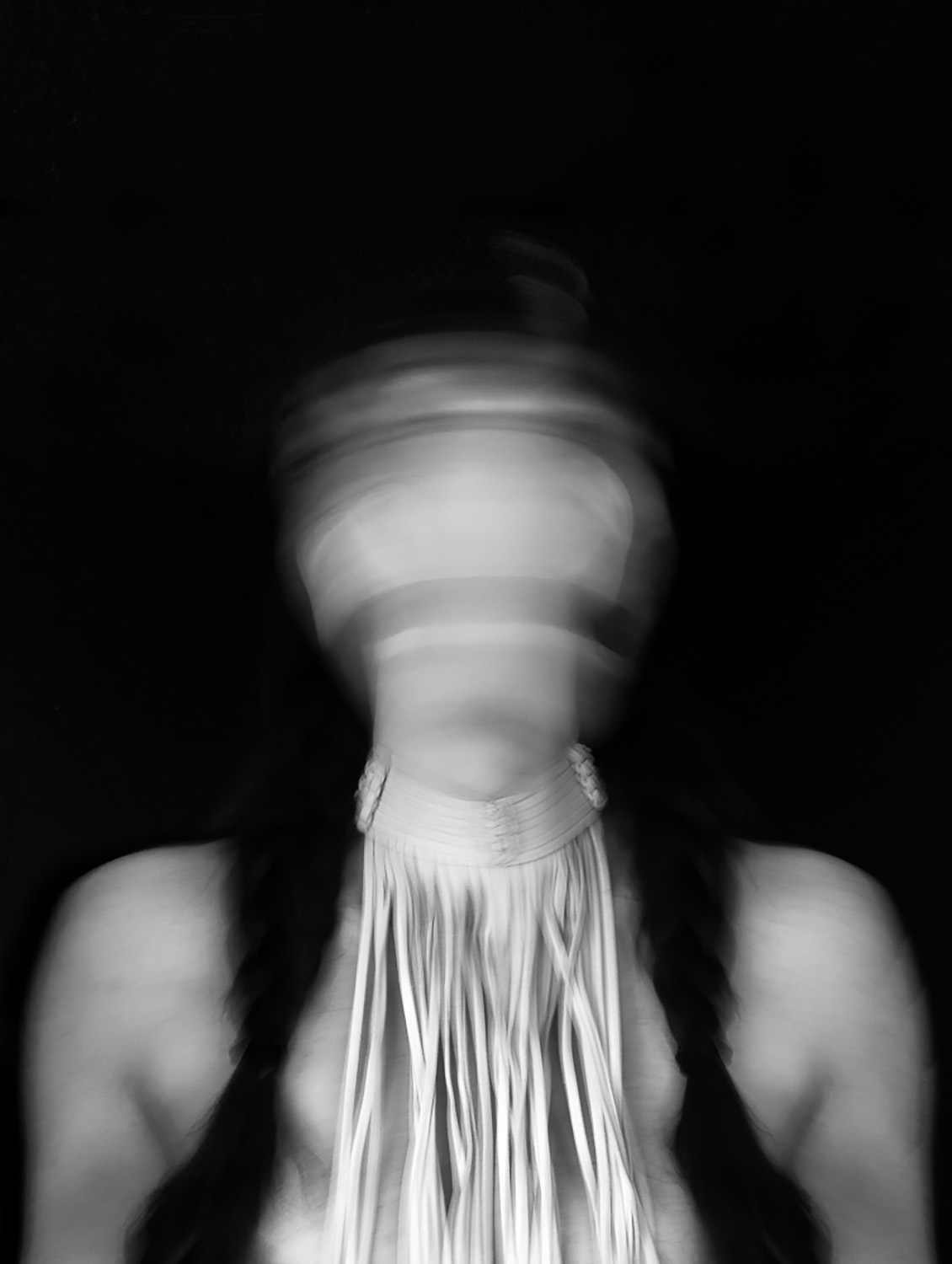

Kali Spitzer is a photographer living on the Traditional Unceded Lands of the Tsleil-Waututh, Skxwú7mesh and Musqueam peoples. The work of Kali embraces the stories of contemporary BIPOC, queer and trans bodies, creating representation that is self determined. Kali’s collaborative process is informed by the desire to rewrite the visual histories of indigenous bodies beyond a colonial lens. Kali is Kaska Dena from Daylu (Lower Post, British Columbia) on her father’s. Kali’s father is a survivor of residential schools and Canadian genocide. On her Mother’s side and Jewish from Transylvania, Romania. Kali’s heritage deeply influences her work as she focuses on cultural revitalization through her art, whether in the medium of photography, ceramics, tanning hides or hunting.

Her partner, Bubzee, is a mixed media artist who was raised by the river of the Slocan Valley settled on Sinixt land. Bubzee creates magic in many forms. She is a weaver pulling together past, present, future and all of the stories they hold, maiden mother, crone, all the creatures on earth. There is nostalgia unraveling here, something ancient and familiar that stem from her creations like remembering a dream -all the light, balanced by dark -all the life, communing with death. Every story told and echoed from the marrow of bones, carried through and brought to life by every piece that she creates. .

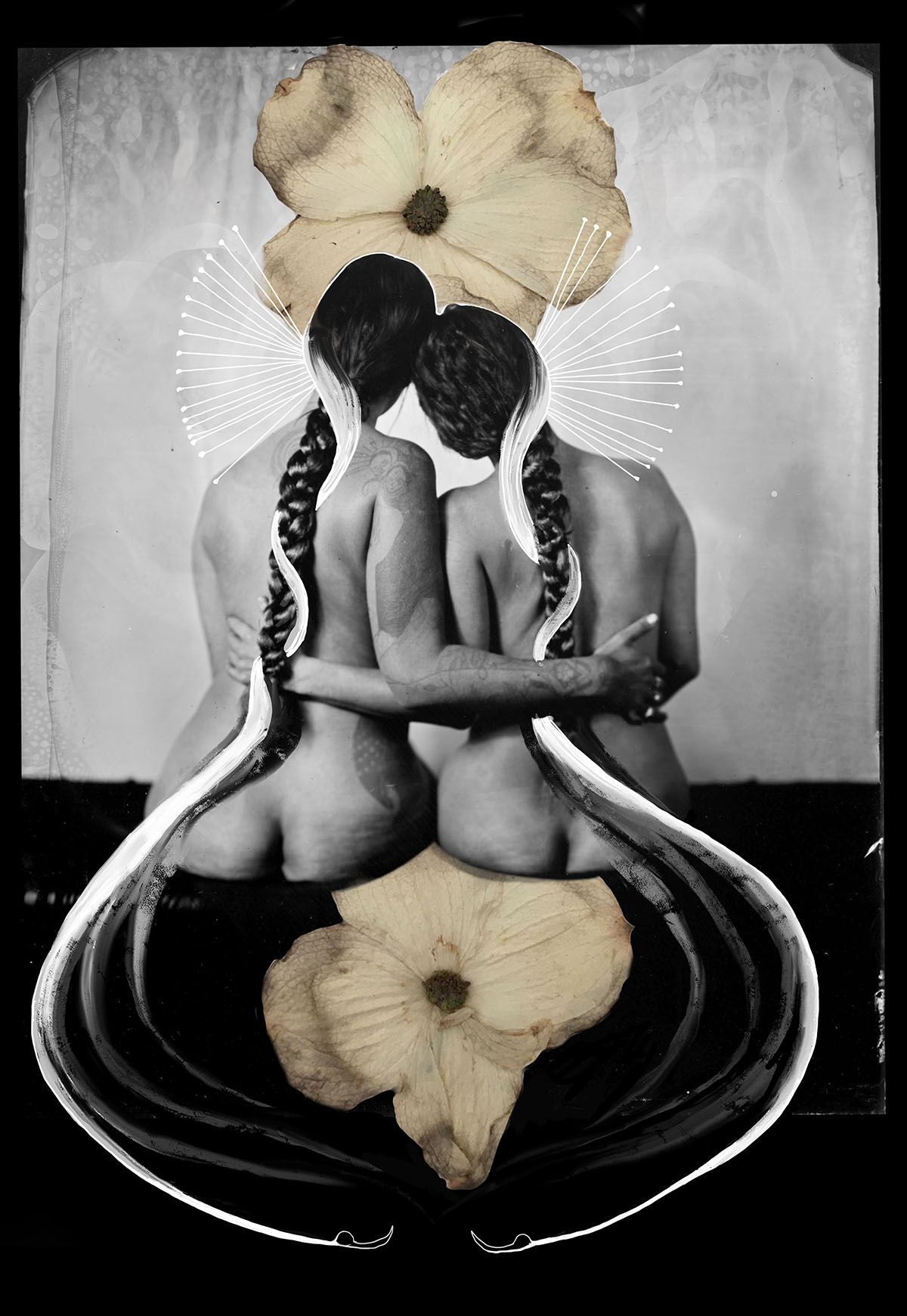

Braiding Wounds

Body as site

carrying blood memory forward.

Interrupted by colonial acts.

Relationships revive

Weaving together the strength of ancestors.

Through generative collaboration, Kali Spitzer (Jewish and Kaska Dena) and Bubzee (European settler) hold space for one another braiding their ancestral connections to heal colonial wounds. Created on the unceded lands of Musqueam, Skwxwú7mesh, Tsleil-Waututh, Sinixt and Mi’kmaq Nation, Braiding Wounds is a series of Tintype images with digital drawings that speak to the restorative labor of caring, deep listening, witnessing, and remembering.

Over the past 15 years, Kali and Bubzee’s kinship grew over their love for art and its capacity to create space for resurgences. Created in the last couple of years, this is a first of a series of collaborations that reveal points of connectivity between them, the continuums of their ancestral strength, and the land towards a deep love and kinship that holds space for one another. Where sites of colonial trauma shift into restorative acts of caring, witnessing and decolonial love.

“Indigenous Femme Queer Photographer Kali Spitzer ignites the spirit of our current unbound human experience with all the complex histories we exist in, passed down through the trauma inflicted/received by our ancestors. Kali’s photographs are intimate, unapologetic and make room for growth and forgiveness, while creating a space where we may share the vulnerable and broken parts of our stories which are often overlooked or not easy to digest for ourselves or society”, according to Ginger Dunnill, Creator and Producer of Broken Boxes Podcast (which features interviews with indigenous and other engaged artists).

Shelley Niro was born in Niagara Falls, NY. Currently, she lives in Brantford Ontario. Niro is a member of the Six Nations Reserve, Bay of Quinte Mohawk, Turtle Clan. Shelley Niro is a multi-media artist. Her work involves photography, painting, beadwork and film.

Niro is conscious of the impact post-colonial mediums have had on Indigenous people. Like many artists from different Native communities, she works relentlessly presenting people in realistic and explorative portrayals. Photo series such as Mohawks in Beehives, This Land is Mime Land and M: Stories of Women are a few of the genre of artwork. Films include: Honey Moccasin, It Starts with a Whisper, The Shirt, Kissed by Lighning and Robert’s Paintings. Recently she finished her film The Incredible 25th Year of Mitzi Bearclaw.

Shelley graduated from the Ontario College of Art, Honours and received her Master of Fine Art from the University of Western Ontario.

Niro was the inaugural recipient of the Aboriginal Arts Award presented through the Ontario Arts Council in 2012. In 2017 Niro received the Governor General’s Award For The Arts from the Canada Council, The Scotiabank Photography Award and also received the Hnatyshyn Foundation REVEAL Award.

Niro was honored with an honorary doctorate from the Ontario College of Art and Design University in 2019.

In March of 2020 Niro received The Paul de Hueck and Norman Walford Career Achievement Award from the Ontario Arts Foundation.

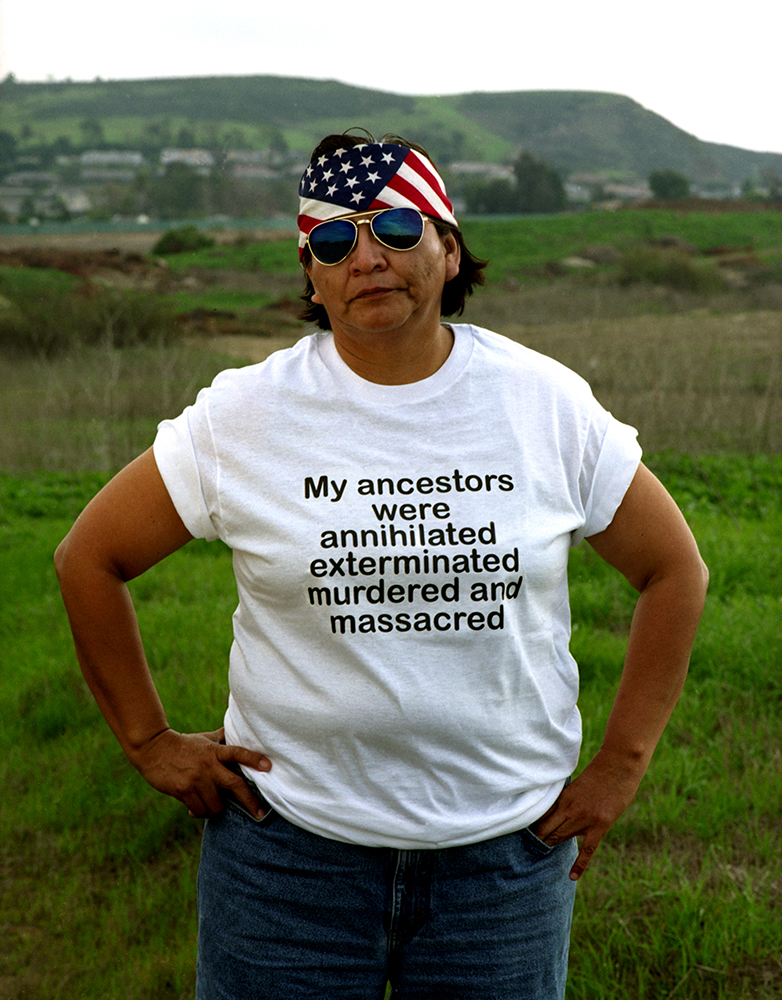

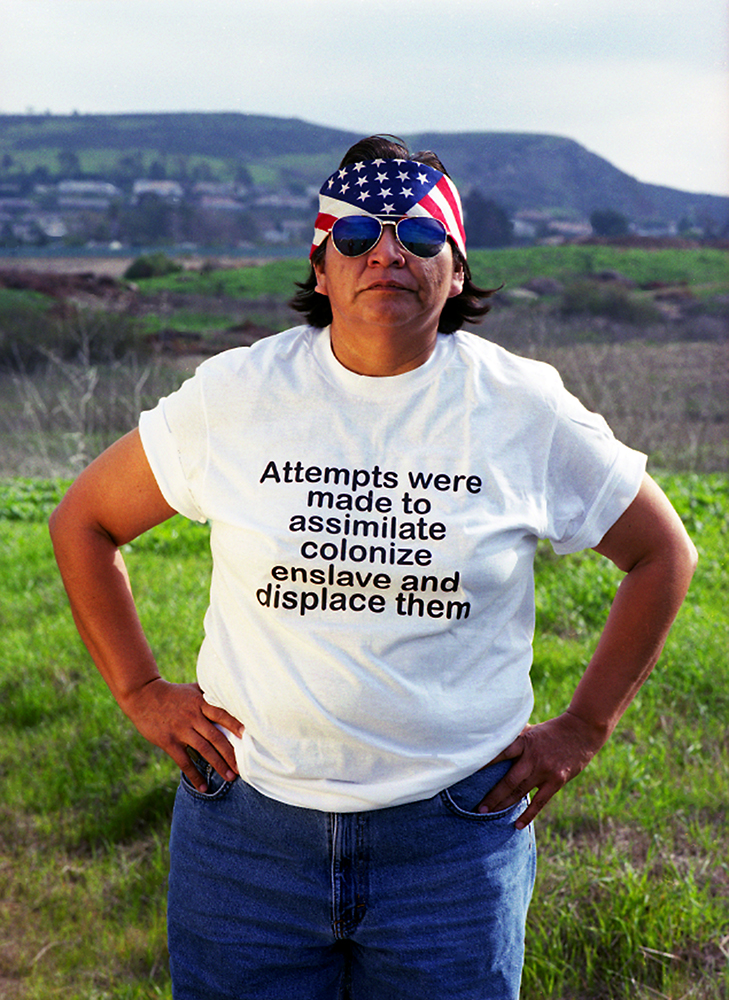

The Shirt

The Shirt is a compelling series of photographs by Shelley Niro that create a narrative of Indigenous sovereignty where women are central.

Although best known for her award-winning filmmaking, Nero’s photographic works often involve performance work by people who she knows as a way of rejecting the clichéd interpretations of Indigenous people in the media. In the series The Shirt, Niro’s friend and fellow photographer Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie of the Taskigi Nation and Diné Nation, faces the lens and directly confronts the viewer. Photographed in a landscape, Hulleah is wearing a series of five T-shirts that sequentially say: “The Shirt”; “My ancestors were annihilated exterminated murdered and massacred”; “They were lied to cheated tricked and deceived”; “Attempts were made to assimilate colonize enslave and displace them”; “And all’s I get is this shirt.” In the sixth image, she appears without any shirt; in the seventh, a smiling white woman wears the final shirt of the series.

Niro twists the archetypal tourist tee shirt from the point of view of First Nations Peoples as an exploration into the lasting effects of European colonialism in North America. According to Niro, The Shirt series came about as she flew over the Texas landscape. Looking out her window, she recalls the way the land below was partitioned, indicating ownership, and how it reminded her of the complex history that took place on that land.

“I looked out of my window and saw the land below chopped up into squares, each square neatly fenced off from the other. I thought about the ‘Indians’ who fought for that land, as well as the sacrifices made by tribes and nations in their efforts to keep away the settlers from their land and communities.” says Niro

Each photograph in the series is set within a literal and conceptual landscape that underscores the importance of land rights to the Indigenous struggles for self-determination. The powerful images show the progression of the shirt from one frame to the next until the Indigenous woman has the shirt literally taken from her back. The shirt becomes a metaphoric remnant of colonization, ripped off the backs of Indigenous women who live there.

Donna Garcia’s work illustrate a semiotic dislocation that has been organically reconstructed in a way that gives her subjects a voice in the present moment; something they didn’t have in the past. Her images rise above what they actually are and become empathetic recreations in a fine art narrative. She has an MFA in Photography from Savannah College of Art and Design and her work has been exhibited internationally. She is a 2019 nominee of reGENERATION 4: The Challenges of Photography and the Museum of Tomorrow. Musee de l’Elysee, Lausanne, Switzerland. Emerging Artists to Watch, Fine Art Photography, Nomination (only 250 lens-based emerging artists nominated worldwide).

Indian Land for Sale

In 1830, the United States government, led by President Andrew Jackson, forcibly relocated native populations east of the Mississippi in order that white farmers could take over their land. The event, known as the Indian Removal Act of 1830, led to a conveniently forgotten genocide, and the extinguishment of the indigenous narratives from American history.

My series “Indian Land For Sale,” attempts to recreate the horror of this event from the perspective of the native tribes. My images serve to replace what has been lost from official historical archives and seeks to sound an alarm, as governments, worldwide, continue to seize ancestral lands and murder indigenous peoples.

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act was enacted along the East Coast of America.

President Jackson declared that Indian removal would “…Incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier. Clearing Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi of their Indian populations would enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power.”

Systematic hunts were made to force indigenous people from their ancestral land.

A Georgia volunteer, later a Colonel in the Confederate service, said, “‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Indian removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

Following the signing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations from their homelands to “Indian Territory” in eastern sections of the present-day Oklahoma. It was a 1,000-mile walk and took 116 days from Georgia, walking all day and only being allowed to stop at night to bury their dead. This is what we now know as the start of the Trail of Tears.

A Cherokee survivor of the trail told her granddaughter, “The winter was very harsh and many of us no longer had shoes. Our feet froze and burst, as we left bloody footprints in the snow. We were not allowed to stop to bury our dead. Many mothers carried their dead children, miles, until we stopped at nightfall. All night you could only hear digging.”

The deportation of indigenous tribes along the Trail of Tears was an act of genocide that has been conveniently forgotten today. My images serve to replace what has been lost from official historical

Not all indigenous people left in 1830, specifically the Cherokee. Many stayed, thinking that they would be allowed to live peacefully or have the ability to fight back (actually winning several legal battles against the removal order). However, the Georgia State government and Andrew Jackson, had plans for their land. Flyers began to circulate hailing “Indian Land For Sale”. White farmers flocked in droves to auctions of indigenous, ancestral land that was still, up to 1838, being occupied by its native people.

It was in 1838 that 7,000 US soldiers in Georgia enforced a final evacuation. The Cherokee, Creek, Shawnee and Choctaw villages were invaded and the people were forced to leave, at gunpoint, with only the clothing on their backs.

For the few who resisted, approximately 1,800, died while imprisoned for refusing to leave.

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of known cholera epidemics, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, 8000 Cherokee died, about half the total population. Half of the Choctaw nation was wiped out and 1 in 4 Creek.

Pat Kane is a photographer in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. Pat takes a documentary approach to stories about people, life and environment in Northern Canada with a special focus on Indigenous issues, and the relationship between land and identity. He’s a grantee of the National Geographic Society’s Covid-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists, and an alumni of the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass.

Mentorship is important to Pat. He offers free training opportunities to promising photographers in rural Northern communities, and is the co-founder and president of the Far North Photo Festival — a platform to help elevate the work of visual storytellers across the Arctic. He’s also a mentor with Room Up Front, a program for emerging BIPOC Canadian photojournalists.

Pat is part of the photo collectives Indigenous Photograph and Boreal Collective. Pat identifies as mixed Indigenous/settler and is a proud Algonquin Anishinaabe member of the Timiskaming First Nation (Quebec). His work has appeared in: National Geographic, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Harper’s Magazine, World Press Photo among others. His photos have been exhibited at Photoville (New York), Contact Photography Festival (Toronto) and Atlanta Celebrates Photography (Atlanta).

©Pat Kane, Melaw Nakehk’o is a moosehide tanner, an artist, a filmmaker and mother. “Through the process of reclaiming my cultural knowledge, I saw how the many teachings woven into our land practices could positively impact our first nation communities. Our Dene protocols and laws govern our reciprocal relationship with the land and animals. Moosehide tanning is a foundational Indigenous art form, it was our homes, our transportation, our clothes and in hard times our sustenance. It is the canvas of our visual cultural identity. The smoke smell triggers memories of grandmothers, the sound of scraping reminds us of our aunties working together, the beadwork and style of our moccasins represent our nations. Hide tanning is a revolutionary act of resistance. We occupy our traditional land, we are adhering to our traditional teachings and honoring our relationship with the animals that sustain us. Moosehide Tanning is Land Back”.

Here is Where We Should Stay

For generations, Indigenous people in Canada have lived under the laws and values of European settlers through forced assimilation. The introduction of residential schools, formed by the federal government and instituted by the Catholic and Anglican Church, pulled Indigenous children away from their lands, families, languages and identities. The goal was to bring “civilization to the savage people who could never civilize themselves” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Final Report, 2015). This project focuses on how Indigenous people in my region are moving towards meaningful self-determination by resetting the past. The act of reclaiming culture and identity is ongoing, and my friends here are resilient in a place where symbols and systems of colonization loom large. We can hear colonization when Dene families pray to the Virgin Mary, but we see Indigenization when a young woman holds the hide of a caribou in her arms. In Catholicism we are Children of God, but in the Dene worldview we are One with the Land. There is a tragic and complex tension between the way of the church and the way of the ancestors. While it may be impossible to break free of the colonizers, the subtle, defiant and beautiful acts of resistance gives strength to say “we are still here; here is where we shall stay”.

©Pat Kane, A dog walks near the Catholic Church of the Holy Family in Łutsël K’é, Northwest Territories. The church was built near the present day settlement in 19XX and moved to its current location at the tip of the peninsula – one of the tallest and most recognizable structures in the community.

The title of this project is from the final story of “The Book of Dene”, a collection of parables from various Indigenous groups in Northern Canada. In the legend titled, “The Two Brothers”, two young siblings sneak away in a canoe and become lost. They travel west, south and east, visiting many different lands but suffering tremendous hardships. Some of the people they meet ridicule and take advantage of them. After many years, they make their way to the North and are welcomed and fed and clothed by the people there. One brother says to the other, “Here is where we shall stay.” An elderly couple asks who they are and the brothers tell their incredible story. It is revealed that these are the boy’s parents, and they are finally reunited as a family in their homeland.

This project was created for the World Press Photo 2020 Joop Swart Masterclass.

©Pat Kane, Moose hides dry and are tanned by the smoke inside a tipi near Lı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́. Moose hide tanning is a traditional way to make clothing, instruments, tools and art. Many younger people in the Northwest Territories are relearning moosehide tanning as a way to Indiginize and carry the tradition forward. “It’s more than tanning moose hide,” says Tania Larsson and artist and advocate for Indigneous practices. “Just by being in the bush with other people, away from the city and making our camp and cooking on the fire and sharing knowledge, we are living our traditional life. It is very holistic, natural approach to living.”

©Pat Kane, In 1987, Pope John Paul II visited the small community of Łı́ı́dlı̨́ı̨́ Kų́ę́, a home to Dene people for thousands of years. It became a fort under the control of the Hudson’s Bay company in the early 1800’s and given the anglicized name Fort Simpson after the George Simpson, the governor of Rupert’s Land. Here, at the ehdaa (a point of flat land) Pope John Paul II wore a caribou hide robe and held mass for nearly 4,000 people. He publicly advocated for Indigenous rights but encouraged Indigenous people to join the Church and follow catholicism. Despite repeated invitations by Indigenous people for the Roman Catholic Church to publicly apologize for their role in the residential school system, they have not. John Paul II was the first and last pope to visit Canada’s North.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026