Focus on Ecuadorian Photographers: Johis Alarcón

©Johis Alarcón, From right to left. Stock photography of Cusubamba, our native town, taken by my great-aunt Hilda Jaque in December 1967. Portrait of my grandmother María Luisa Jaque holding the carrot seeds that we will sow in the garden. July 7, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.Johis Alarcón UN Women maintains that the relationship between women and the care of the environment is fundamental in pandemic time, women transmit the connection to the land and lead the management of natural resources.

This week we are featuring the work of Ecuadorian Photographers. Ecuador straddles part of the Andes Mountains and occupies part of the Amazon basin. Situated on the Equator, from which its name derives, it borders Colombia to the north, Peru to the east and the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. We start this week with Johis Alarcón.

Johanna Alarcón (1992) is a freelance photojournalist and visual storyteller based in Ecuador.

Johanna´s work is focused on social justice, human rights, and gender related issues. She is a National Geographic Explorer and member of Ayün Fotógrafas, Fluxus Foto, Visura.Co, Fotoféminas, Women Photograph.

Selected for Photography and Social Justice Fellowship Magnum Foundation (2021), Joop Swart Masterclass World Press Photo (2020), 6×6 Global Talent South America (2019). Her work has been published in The New York Times, Bloomberg, Volkskrant, Reuters, among others. Selected for the New York Times portfolio review (2019), Eddie Adams and Women Photograph Workshop (2019). Her work has been exhibited in Montevideo Photography Center (2021), Photoville Festival and Latin American Photography Festival Bronx Documentary Center (2019-2020).

Her recognitions include: Community Awareness Award Photographer of the Year International (2021), First Place in Photographer of the Year Latinamerica Health Category (2020), FotoEvidence Book Award – CovidLatam (2021), Grantee of COVID-19 Magnum Foundation Found (2021), Open Society and Gabo Foundation’s fund for investigations and new narratives on drugs (2020), Will Riera Award (2019), Everyday Projects and Visura Co Mentorship (2018-2019), AECID Africamericanos Grantee Ecuador (2018), Tutor of the 20f Campament in Bolivia (2018), Honorable Mention in the photobook competition RM (2017) Currently, she works on assignments and her personal projects.

Currently, she works on assignments, teaching and her personal projects. Follow on Instagram: @johis.alarcon

©Johis Alarcón, The altar of my mom stays at home for protection and abundance in the family. The women’s rites have passed down through the generations as a spiritual connection. July 11, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.

The fear of losing them made me return: my land, my mother.

We are a land that feels, land that cries, land that thinks, that suffers and regenerates…

In a world where we are bombarded with a predatory consumption and overrated individualism, the pandemic shows us how simple life can be when we return to our essence. A ti Vuelvo explores the female sense for the protection of the earth as a way to preserve mental, physical and emotional health. The transcendence of the knowledge that the generations behind have communicated to us, and that we will take to future generations.

More than 50 years ago, my family had to move from the small town on the slopes of the Cotopaxi volcano to Quito, the capital of Ecuador. My great-grandmother, my grandmother, my aunts, and my mother arrived in the city, separated from Cusubamba. Their knowledge of planting, healthy eating, animal care, and community life survive as distant memories amid chaotic capital life. Since the quarantine began, we started a return trip as a symbolic way that allows us to deal with the experiences of this time.

The severity of the health crisis facing the world has led us to consider alternatives for post-COVID-19 scenarios focused on a sustainable development strategy that prioritizes the use of natural resources and the harmonious coexistence between human beings and nature. These innovation approaches and leaves us some inspired clues where to continue exploring our future actions with the application of alternatives that do not compromise a healthy and sustainable life for new generations.

This project is part of an Ayün Fotografas collective’s work “La naturaleza que nos habita,” or “the nature that inhabits us,” explores the problems leading up to the pandemic, such as environmental deterioration, destruction, and exploitation as well as overpopulation, pollution, and detachment from nature. While most of our stories hail from Latin America—one of the world’s most biodiverse regions—our stories extend beyond this region, ensuring a global perspective. Our work will also highlight the important work of activists and organizations throughout these regions fighting to reverse these negative impacts.

Supported by National Geographic Society COVID/19 Emergency Fund for Journalist

©Johis Alarcón, Portrait of my grandmother María Luisa Jaque during the return to her mother’s house in Cusubamba. The WHO (World Health Organization) promotes the return to the field as an alternative that reduces the risk of contagious. July 12, 2020.

What was the first image or circumstance that motivated you to photograph?

I was part of juvenile organizations and had experience with cultural management. Namely, “La Sarta Indígena”. We used to create graffiti, murals, street art, workshops in schools and markets. We needed to share what we were doing and what was happening and that was how the camera became an ally. I told people and artists’ stories about the societal impact of those encounters.

“La Sarta Indígena” began 12 years ago in the southern part of Quito. Creative actions were taken in our neighborhood, we were in the south in the 90s and it became our means of living, being and reconciling as an alternative to the violence we were living. “La Sarta” is an important connection to our identity because it began on the streets and was expanded to different spaces.

The person who organizes this group is my partner, so that was the beginning of our love story.

©Johis Alarcón, The flowers of beans grow up in my garden. During the health emergency in Ecuador, a large percentage of the young population returned to work in the land and orchards as a sustainable and self-care economy solution. July 7, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.

©Johis Alarcón, Self-portrait in the beans of my garden. Since the pandemic has started, I felt the instinct to go back to earth, to the mother During the health emergency in Ecuador, a large percentage of the young population returned to work on land and in the farms as a solution for sustainable economy and self-care. July 7, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.

Which fields and people have inspired your photographic work?

I believe I have had a close relation to the arts in general but I have always been associated to street theater. In fact, I used to do theater and that led me to aesthetics, conceptualization and to notice the importance of corporeality. I attempt to present these in my photographs, to find the body and those languages that are less figurative and more intimate. I think that the body stores stories and reveals them unconsciously.

Urban movements have been an important source of inspiration; punk, hip hop, reggae and experiences with friends have contributed a great deal. My photographic references are cinematic, like “Amarte Duele”, “Pandillas Guerra y Paz”, “Amores Perros”, “Noviembre”, etc. Some photographers have also influenced my work, such as Imogen Cunningham, Nan Golding, María Godet, Graciela Iturbide and Alejandra Sanguinetti. With regard to literature, since I was very young I collected many books by Isabel Allende and I wanted to illustrate her stories. That’s how multiple references have come together for my work, it’s constant research. Nowadays, my greatest inspiration is the work of contemporary latinx women and also men who photograph. Lastly, there is also a lot of work I’m doing with collectives. Namely, Ninja, “Sur”, “Mirar”, “Trasluz” and I know I am missing a few!

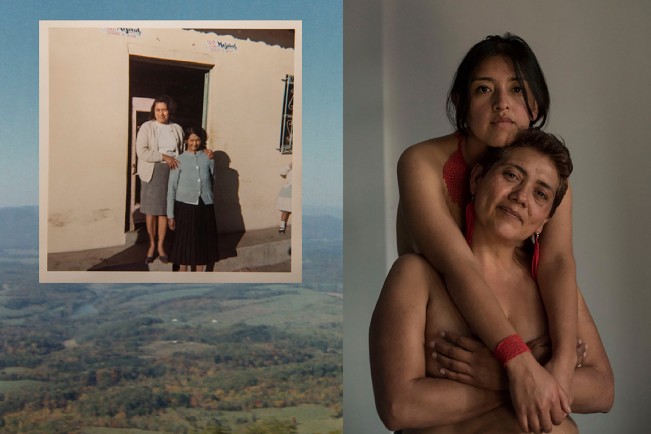

©Johis Alarcón, From left to right: Portrait of my great-grandmother Celia Ortega Jaque with her daughter María Luisa Jaque (my grandmother) at the Cusubamba house. Family archive 1967. Self-portrait of the first hug with my mother after confinement. July 9, 2020. Quito-Ecuador. Johis Alarcón. Grant McCracken, PhD in cultural anthropologist with decades of experience studying American families has found that during COVID-19 lockdowns, many parent-child relationships are improving, especially the bond between mothers and daughters. “This pandemic, this international turmoil, removes this disconnect and allows for the bridge to be made on through the commonality of suffering,” he said. At the same time that we improve our relationship with our mother, we improve our relationship with nature.

©Johis Alarcón, Self-portrait with my mom Mónica Alvarez, in my teenage room. Every day the fear of contagious grew up, she is a doctor, and I enjoy hugging her when she back home. When she is not there, her plants are our medicine. July 18, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.

What does the act of documenting require?

To me, the main requirements are honesty, empathy and the desire to create a connection through the gaze. I am part of the stories that I tell. That is to say, I have a relationship with the people I photograph, I know their context and I know the topics that I really care about. I tell people about my interests and my doubts during the process. I seek for similarities that might disclose people’s humanity.

I have been very lucky but I have also hit the wall a thousand times. However, that has helped me face my fears and question stereotypes. I am grateful for what surrounds me, for what is in my heart and for having the ability to meet people. I believe that this feeling, when it is shared with others, gives you a sign to choose and follow the right path. I am also very persistent, tenacious. Photography has also been a cathartic tool in difficult life circumstances. As one of my mentors used to say, photography stops being an act of shooting when it becomes a meditation. Photography connects and it is difficult to stay away from it. Finally, research is very important, from academic sources to experience.

©Johis Alarcón, María Luisa Jaque, my grandmother, sunbathes on the terrace. Almost 16% of the cases of COVID-19 in Ecuador are elderly, the high risk of contagion for being diabetic has kept my grandmother in confinement since March. July 17, 2020. Quito-Ecuador.

©Johis Alarcón, Paper trees in the high mountains of Cusubamba, where my great-grandmother’s house was. In the face of the pandemic, the WHO (World Health Organization) recommends that young people return to the field, due to the health benefits and the lower risk of contagion. July 31, 2020. Cusubamba-Ecuador.

©Johis Alarcón, Portrait of my cousin Pamela Gonzáles in the during our return to our great-grandmother’s house. In the face of the pandemic, the WHO (World Health Organization) recommends that young people return to the field, due to the health benefits and the lower risk of contagion. July 12, 2020. Cusubamba-Ecuador.

How have you faced the dangers that derive from your profession?

Everyone believes they can go out and document without any repercussions. However, being prepared is a requirement. What is essential when facing violence is preparedness with regard to safety, this is not negotiable and it is professional. During this mediatic exercise, during the boom, there is too much information and you risk your life for that iconic image that will stand out. At the time of the “Octubre” manifestations I knew the space and planned ahead with my collective. I am part of Fluxus, a photo collective, and as a group we were able to communicate and take care of each other. We organized and had all our personal information, blood type, insurance, emergency contacts and all the safety protocol ready. I wore a helmet, carried my first aid kit, a mask and that allowed me to work with reassurance and in a professional manner. If you are fearful and do not take the necessary precautions, the image will show that. However, there are many latent risks like not showing that you are a press member and I worry about my identity even when publishing my work. Images are held as a representations of a specific location and there are many risks and responsibilities with the appropriation of that perception.

It is also important to ask oneself: What happens with my images on an international scope? Are they analyzing and researching the topic?

A great outcome is a community of photojournalists who demystify the idea of the lonely photographer and that is important for our security.

©Johis Alarcón, Cardono flowers growing up in the high mountains of Cotopaxi. My grand-grandmother use it for her work on the farm. July 31, 2020. Cotopaxi-Ecuador.

©Johis Alarcón, Portrait of my aunt Martha Jaque with the flowers in the garden. July 18, 2020. Quito-Ecuador. Johis Alarcón According to the UN (United Nations Organization), in times of pandemic, it is essential to promote the relationship between women and the environment, their sensitivity for the care of natural resource management is transmitted from generation to generation.

What does it mean to be a woman in Ecuador? Have you felt excluded because of being a woman?

As an Andean and Latin American woman, my career has had various difficulties and opportunities. First, let’s talk about security. On a national scale, and I am sorry to say so, there have been many obstacles but I have not had any abroad. In fact, when working abroad my identity and gender have been an asset and that’s something I always question. Luckily, I have not had any violent harassment or assault experiences as other colleagues have had. Still, those experiences that came close to being violent required boundaries and a firm no to uneasy circumstances. Maybe if I were a man, I’d stay over and I’d continue working. I do have to consider who’ll come with me to feel safe. I believe that male colleagues might search for a partner but not precisely to avoid sexual violence.

Plus, there’s this image of what a photographer must look like; a man, tall, many cameras and lenses, a foreigner, etc. As soon as you come along, they don’t believe it, they can’t believe you are the photographer. There is no credibility nor recognition of my skills and capabilities. It is hard to access institutions, people confront me with questions such as: Are you on your own? If you are, you cannot come in. Are you press? I don’t think so.

But as I said before, I am stubborn so when I hear people say that this is only for men, I take it as a challenge and just do it. There are also historic difficulties, it has been complicated to find information on Latin American women photographers. It’s a complex topic because there’s also a lack of referencing and when trying to identify images with a feminine gaze, you find yourself in a historic vacuum.

©Johis Alarcón, The women of my family Martha Jaque, Pamela Gonzáles, Mónica Alvarez, and I weave our hair in the patio of my great-grandmother’s house. July 7, 2020. Cusubamba-Ecuador.

©Johis Alarcón, Portrait of my aunt Martha Jaque during our visit to my grand-grandmother house. July 12, 2020. Quito-Ecuador. Johis Alarcón According to the UN (United Nations Organization), in times of pandemic, it is essential to promote the relationship between women and the environment, their sensitivity for the care of natural resource management is transmitted from generation to generation.

What is your goal when creating photographs?

One of my clear views is that there is not only one story. I believe that history has been told many times, but it’s been the same, the most powerful one. There are other ways to tell the same story that when visible can provoke something, or not. There might be space for feelings and dialogue.

Regarding portraits, they are a consensual collaboration. I do not like the idea of the subject, neither as a word nor as a concept. An anthropologist once told me something that made everything so clear. She spoke about sameness, sameness is a consensual representation in which the peron who’s being represented is open for dialogue in order to create the image. Particularly for portraits, I speak to people, sometimes with words, the body, or my gaze, etc. It’s important not to impose our ideas, I ask questions and want the portrait to be fair to who I am representing.

©Johis Alarcón, Self-portrait sharing time with my grandmother María Luisa Jaque. During the quarantine, I can’t see her. I miss her because she taught me all the protection of the earth. The unique way to be connected with her was trough my relationship with nature around me. July 18, 2020. Quito-Ecuador. Johis Alarcón According to the UN (United Nations Organization), in times of pandemic, it is essential to promote the relationship between women and the environment, their sensitivity for the care of natural resource management is transmitted from generation to generation.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025