Eirik Johnson: Photographing the Far North

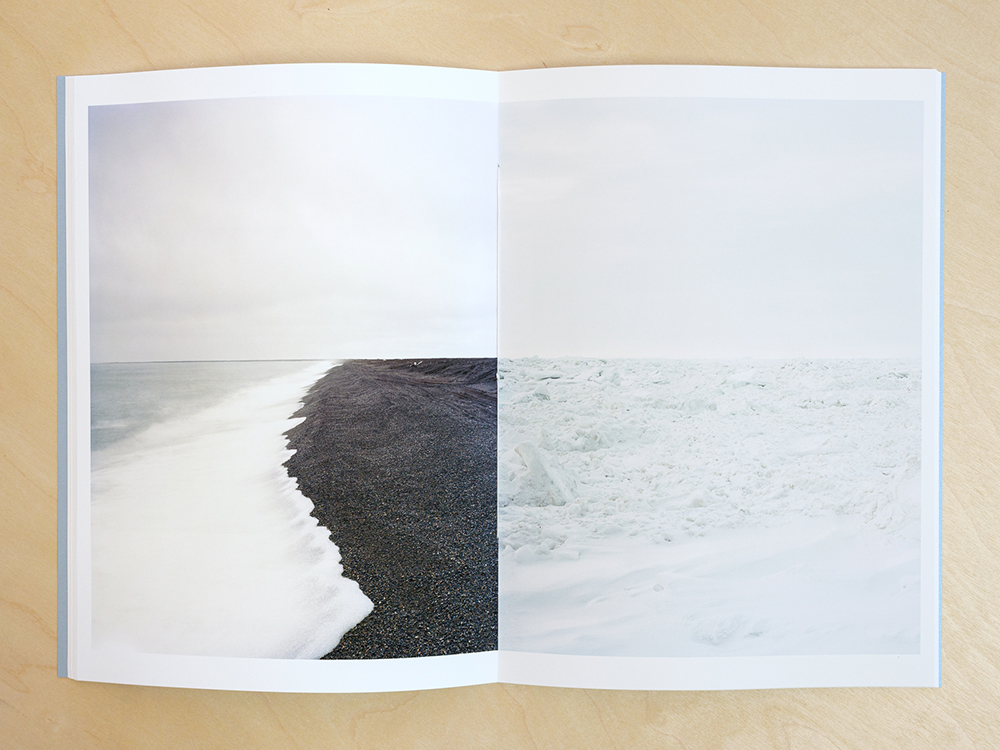

Every place, every swath of tundra, every stretch of ocean contains multitudes. Depending on season, time of day, and level of human intervention, the way in which a landscape is experienced greatly varies. Few photographic works depict this phenomenon to greater success than Eirik Johnson’s Barrow Cabins. Johnson’s measured and methodically balanced images of hunting cabins constructed by the native population in Utqiagvik, Alaska feel more akin to portraiture than landscape. The intimate curiosity and quiet expressiveness contained within these pictures bestow the viewer with a sense that not only is Johnson observing and engaging with these structures, but that he too is being observed by these makeshift abodes and the surrounding horizon. In its book form, a diptych of snow and sea divide the summer and subsequent winter visions of this place. Time is present in Barrow Cabins and yet perhaps not in a strictly linear sense. Here, we cease to feel the circular flow of seasons and experience this arctic habitation as a turned-over coin. On one side, the weary glow of summer sun and gently warmed earth. On the other, an endless expanse of snow nearly indistinguishable from sky. Twin vistas that share a precise geography, and yet, are never to be seen at once.

Photographic artist Eirik Johnson (b. 1974) employs various modes of presentation from photobooks to experiential photo and sound-based installation to explore the marks and connections formed in the friction of contemporary environmental, social, and economic issues. Johnson received his BFA and BA from the University of Washington, Seattle, WA in 1997 and his MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2003. He has exhibited his work at institutions including the Aperture Foundation, NY, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston MA, and the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY. His monographs include Road to Nowhere (self-published), Barrow Cabins (Ice Fog Press), PINE (Minor Matters Books), Sawdust Mountain (Aperture Books), and BORDERLANDS (Twin Palms Publishers). Johnson’s work is in the permanent collections of institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the International Center of Photography, NY, and the Nevada Art Museum, Reno, NV. Eirik Johnson is represented by Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco and G. Gibson Projects in Seattle. He is a member of the photographic cooperative Piece of Cake Collective and serves as Programs Chair at the Photographic Center Northwest.

BARROW CABINS

These pictures depict seasonal hunting cabins built by the native Iñupiat inhabitants of Utqiaġvik (formerly known as Barrow), Alaska as seen through the extremes of the Arctic summer and winter. The cabins are situated on Point Barrow, an isthmus at the Northern most stretch of the United States, along the shores of the Chukchi Sea, part of the larger Arctic Ocean. Iñupiat families travel from Barrow to the cabins to hunt for waterfowl in the summer and bowhead whales and seals in the winter.

“Barrow Cabins” is an extension of my continued interest in shifting cultural and environmental modes of improvisation in the face of environmental change. Each structure has been fashioned out of whatever makeshift materials are on hand, from weathered plywood to old shipping pallets collected from the nearby-decommissioned U.S. Navy Base, which has itself been refashioned into a hub of climate change scientific research.

Children’s swings are rigged from two by fours and plastic milk boxes, while old school chairs and car seats serve as patio furniture. Scraps of carpet and particleboard become footpaths across the loose ocean gravel and spongy permafrost tundra. I first photographed the cabins in 2010, in the midnight and early morning hours of the Arctic summer when the sun hangs almost perpetually at the horizon. The hunters were gone, their cabins and the hunting grounds empty.

In December 2012, I returned to photograph the cabins during the frigid grip of the Arctic Winter Solstice, when a brief four-hour window of dusk-like light illuminates the otherwise lightless days. The resulting winter images act as a sort of “negative” or luminous white erasure of the photographs made during the summer. Seen together, both the summer and winter series are a meditation on the passage of time and the fragile seasonal shift along the extreme horizon of the Arctic.

To begin I’d like to hear about what sparked your interest in the arctic. Can you recall your first introduction to the Utqiagvik region?

When I was a child, my father had traveled throughout the arctic slope region of Alaska including Utqiagvik, then called Barrow, while working on tribal native rights law in the early 1970s. His stories of the vast arctic landscape had stayed with me. It wasn’t until 2010 that I traveled there myself on assignment. I was working for an environmental group that was monitoring the plume of chemicals beneath the tundra left over from the former naval base. I traveled there in the summer, when the sun never sets in the arctic. After photographing the scientists working in the field during the day, I would venture out on my own to explore.

What were some initial musings you had when conceiving of this project? How did the reality of making the work contrast with these early ideas?

I didn’t think of the work initially as a project. Rather, I thought of it simply as a small series of pictures exploring the makeshift architecture of the seasonal hunting camp. I thought about each cabin as a portrait of their maker in a sense, each reflecting the choices and sensibilities of those who constructed them. Some are quite humble, others more elaborate and unique.

It was only later, once returning to photograph the same structures during the arctic winter when the sun never rises completely, that the work evolved more deeply into a project. In addition to the initial idea of architecture as a form of portraiture, the work began to reflect the larger concept of seasonal extremes in the arctic. The arctic winter pictures act in a sense as an erasure of their paired summer photographs.

These images are devoid of physical human presence and yet I wonder if on your journey you received help and guidance from locals who bore a greater understanding of the area. If so, who were these people and what was their impact on the project?

You’re correct in that there is no overt or apparent human presence in the pictures. It was by choice in that I wanted the cabins to take on their own personality in a sense or as I mentioned, to reflect the personalities of their makers. To be sure, I was guided by folks within the Utqiagvik community who had introduced me to the seasonal hunting camp which lies outside of town.

It can be difficult to know where a body of work should begin and end. What limitations did you put on yourself for this work and how did you decide that it was complete?

When I returned home from making the summer photographs, I thought the pictures were interesting but felt the idea was incomplete. It took me some time to conceptually make the leap to the idea of returning to photograph the same cabins during the Winter Solstice, but once I had done that the work felt complete. The longer I’ve worked as a photographic artist, the more I feel that projects or ideas don’t have to take form as massive bodies of work. A concise idea well executed often makes for an elegant and powerful project.

You mention imploring various methods of presentation when it comes to your work. Beyond the photobook format do you have other aspirations as to how these images might be shown?

The photobook allowed me to explore a certain narrative structure for the work. Ben Huff, publisher at Ice Fog Press, had initially suggested the idea for a book of this work. Ben generously brought his own ideas and approach to developing the book and I’m very honored to have collaborated with him on it. I’ve also had the opportunity to present the photographs in several gallery exhibitions and in each case, I’ve paired a large diptych of the Arctic Ocean with audio I recorded of the ocean waves crashing onto the shores near the hunting camp. I’ve become more fascinated with the relationship between sound and image and the possibilities of pairing photographs with sound-based installations.

I have found in my own work that projects often lead to other projects. Was this the case with Barrow Cabins? If so, what project led you there and what came/is coming next?

That was definitely the case with the Barrow Cabins work as well. Prior to my work in the arctic, I had completed a project entitled “Madre de Dios” which similarly used photography and sound to explore the primordial landscape of the Peruvian Amazon. That work gave me the confidence to continue using sound with the Barrow Cabins project. Later on, I continued to follow my interest in makeshift architecture with my project “The Mushroom Camps”, photographing amongst commercial foraging encampments in the mountains of Oregon.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026