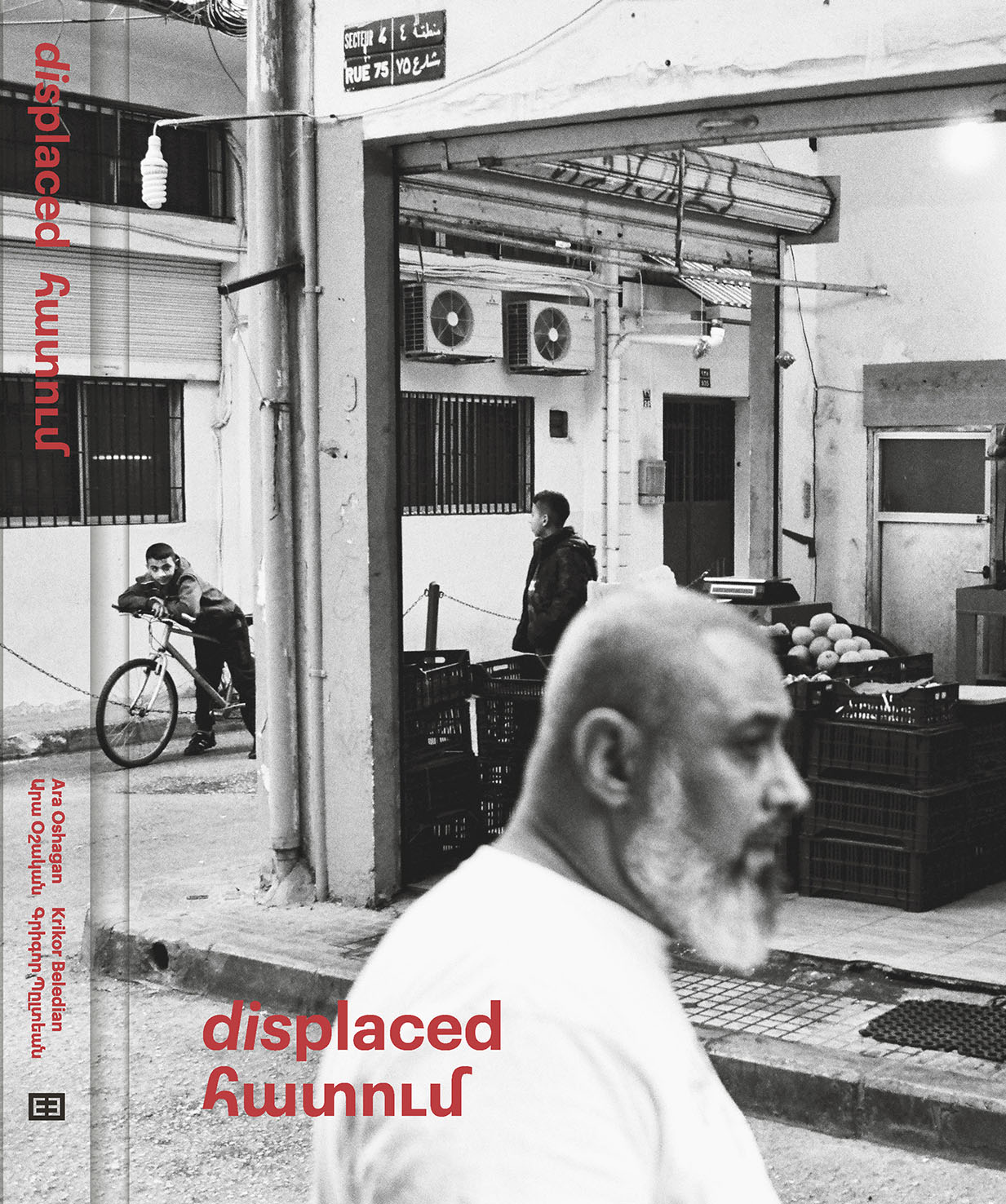

Ara Oshagan: Displaced

Excerpt from the text by Krikor Beledian:

Down from The Hill, beyond the river, is Giligia, as you call it. Nor Sis, Nor Adana, Nor Marash, Nor Amanos, Nor Tomarza, Nor Yozghat2—you rattle them off in a single breath. Giligia lives again, right here—who knows until when?—in its legendary names. The bridge is its official gate. But in the summer or during autumn days, all of you prefer the alternate route. When you descend The Hill, you enter directly the shallow flow from the tree-lined street that edges the river.

Photographer Ara Oshagan and author Krikor Beledian grew up in Beirut’s Armenian communities formed by refugees and survivors of genocide. They came of age in families and streets fraught with the collective memory of extreme violence and dispossession. Both left Beirut decades ago and now return, carrying their own histories of displacement, to immerse them- selves in its fractured urbanscape. Oshagan wades through the spaces and narrow neighborhoods of his past to create dark and lyrical photographs that straddle the line between documentary and narrative: an attempt to articulate his own ambiguous relationship to place and history. While Beledian, the preeminent author of the Armenian diaspora, drawing from his decades-long research and several novels about these communities, pens an original and poetic semi- autobiographical text based on his own youth in the same spaces. Set in Beirut’s dense Armenian neighborhoods of Bourj Ham-moud, displaced brings these two symbiotic and deeply personal works of literature and photography together: a unique collaboration interrogating diasporic identity, multi- generational displacement, and the ambiguities of narrative. displaced is published by Kehrer Verlag is to be released in US on May 10th. The book can be ordered HERE.

Text by Krikor Beledian

Translation by Taline Voskeritchian, Christopher Millis

Designed by Kehrer Design (Lisa Drechsel)

Hardcover, 19 x 25 cm

160 pages

58 duotone illustrations

English, Armenian

ISBN 978-3-96900-014-4

Euro 38,00 /US$ 48.00

Ara Oshagan is a diasporic multi-disciplinary visual artist, curator and cultural worker working in photography, film, collage, installation, book-arts and public art. His practice explores collective and personal histories of dispossession, legacies of violence, identity and (un)imagined futures. A descendant of communities uprooted from their indigenous land by the Armenian Genocide, Oshagan was born in diaspora and was displaced again to the US as a youth.

His first book, Father Land, in collaboration with his father author Vahe Oshagan, was published by powerHouse books in 2010. His second book, Mirror, was self-published in 2016. His third book, ‘displaced’ published by Kehrer Verlag in Germany, was released in 2021. He has presented his work at the Annenberg Space for Photography and TedX Yerevan and has had solo exhibitions at the Seongbuk City Gallery in Seoul, Korea, LA Municipal Art Gallery, Downey Museum of Art, Pasadena Armory Center for the Arts and Tufenkian Fine Arts in Los Angeles. His work has been reviewed and featured in the Virginia Quarterly Review, LA Times, LA Weekly, NPR’s Morning Edition, Curbed LA, LA Magazine, Associated Press, Hyperallergic, Artillery Mag, Mother Jones and the London Times Literary Supplement among others. His work is in the permanent collection of the Southeast Museum of Photography, the Downey Museum of Art, the Pasadena Armory Center for the Arts, and the MOMA in Armenia.

In 2015, for iwintess, a large-scale public art installation in Grand Park DTLA, Oshagan, along with the iwitness team, were selected as one of “100 Leading Global Thinkers” by Foreign Policy Magazine in DC.

In September 2016, Oshagan and the iwitness team installed the first permanent Genocide monument in the City of Los Angeles in Grand Park.

In 2017, iwitness public art was installed in the Glendale City Central Park. In 2018, Oshagan was selected as a “Cultural Trailblazer” by the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.

In 2020, his public art installation, Alight, debuted in Seoul, South Korea.

Oshagan is married to Anahid Oshagan and a father of four. He is currently is a co-curator of ReflectSpace Gallery in Glendale, CA.

Follow Ara on Instagram: @ara.oshagan

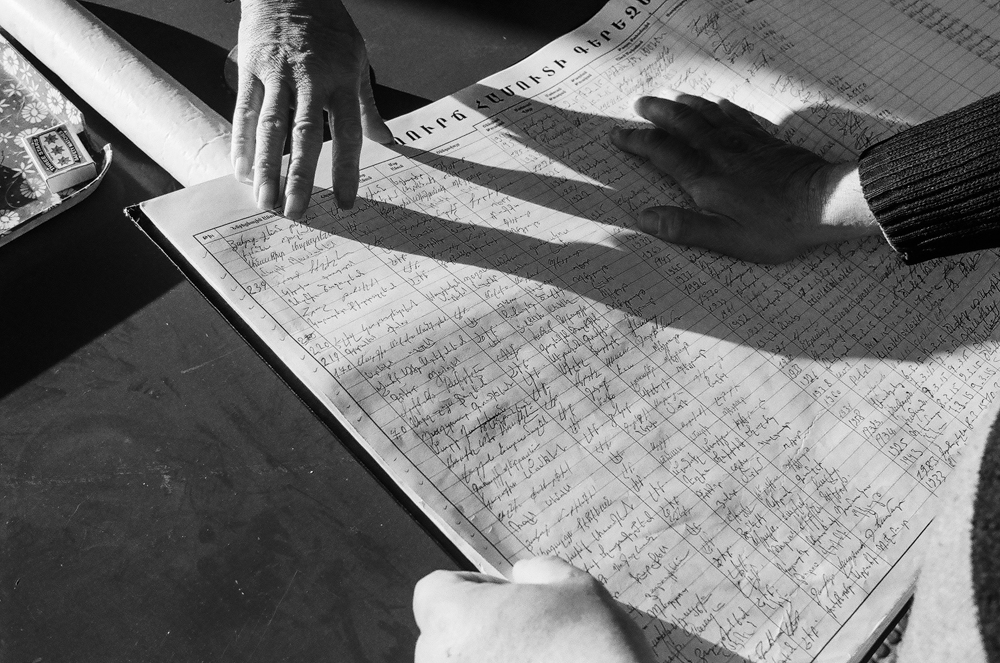

Krikor Beledian is widely regarded as the most important poet writing in Western Armenian. A prolific novelist, essayist, and literary critic, he is the author of more than 30 volumes that have been published in the Middle East, Europe, Armenia, and the United States. Born in Beirut, Lebanon, and a long-time resident of Paris, for the last half-century Beledian has chosen to write almost exclusively in Western Armenian, a UN-designated endangered language. Since 1997, he has written a series of novel-length semi-autobiographical narratives exploring post-Catastrophe generations of Armenians in Beirut. “The Bridge”, an original text he wrote specifically for this volume, is similar in nature and is set in Beirut in the 1950s.

Taline Voskeritchian’s work, including translations of the modernist Armenian poet Vahe Oshagan, has appeared widely in the U.S., Europe, and the Middle Eat; she teaches at Boston University.

Christopher Millis is the author of four Off Broadway productions and five books of poetry, including translations from the Italian of Umberto Saba.

Voskeritchian and Millis’ co-translations of Mahmoud Darwish and Krikor Beledian have appeared in London Review of Books and Los Angeles Review of Books.

Displaced

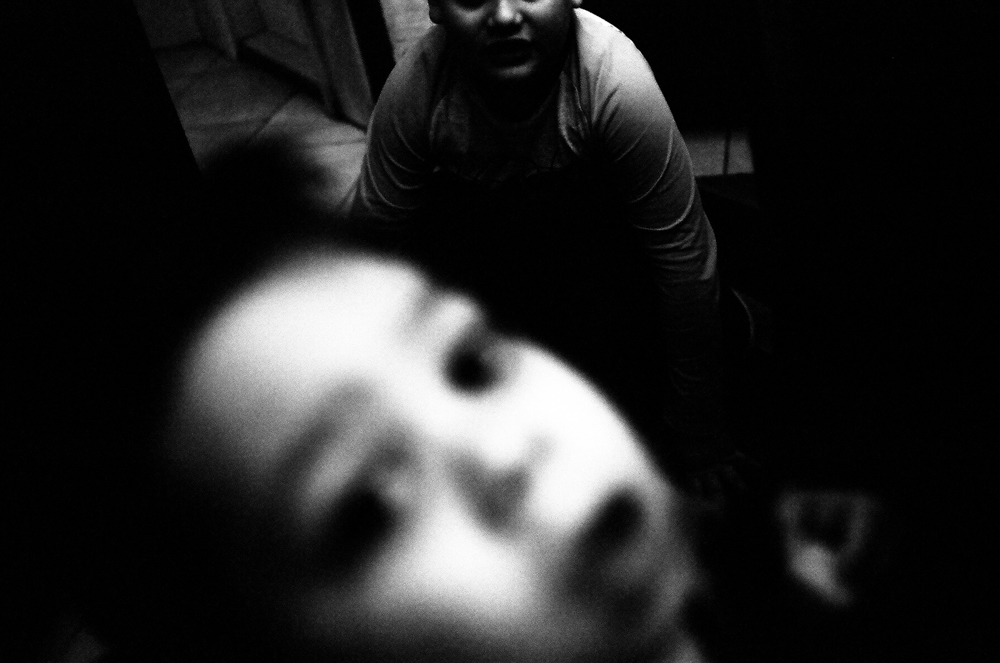

There is a landing here, a foyer, on the second floor of a stone-built house, here in the mountains above Beirut. A landing made of stone tiles where four doors keeps watch over this deserted space, silent and cold, in this traditional stone house. Here I spent my summers as a child. And here, now, 40 years later, on this same tiled landing, I am overwhelmed: in this deserted space, among the silence of the tiles, I see myself: a past and a present, intertwined, interrupted, torn, inseparable. How to begin?

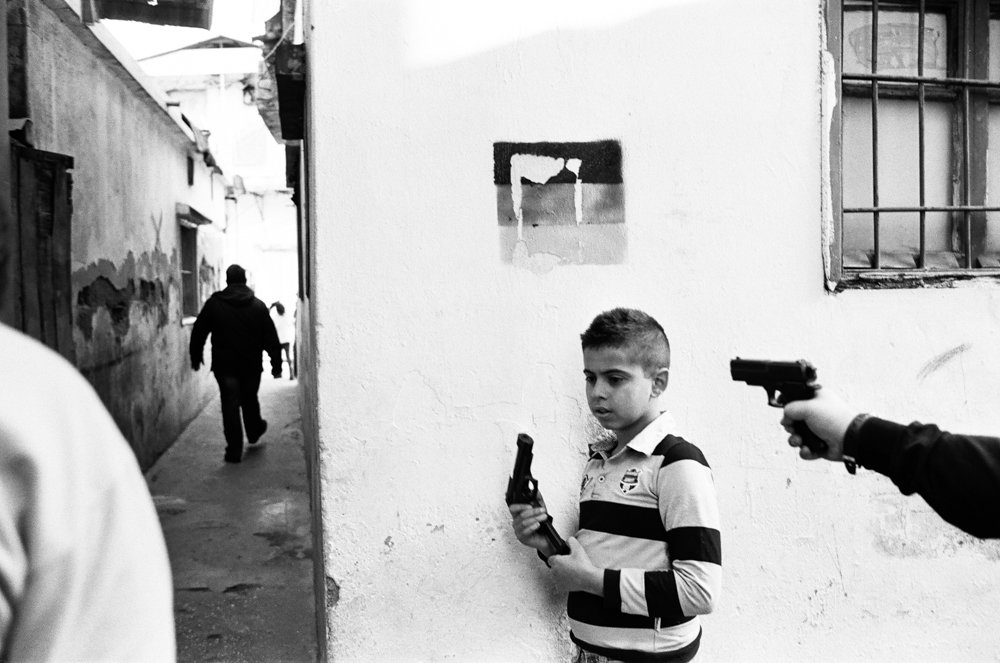

I am child and I am running. Through woods, among dark thin trees, scattered pine cones; I am climbing, reaching for the lower branches, hoisting myself up, throwing down pine cones, picking berries from oversized berry stoops, clearing pathways of thorns, riding bikes on dirt, over hills, into rocks. I am running, always running.

I am running on pavement now with my best friend at my heels—we have fled school at lunch and are running downtown to find our favorite comic books; we are running past gardens with worn fences, strewn garbage, chaos and noise of cars, past the street hawkers, shoe salesmen, nail salons, men in neat suits and women in purple hats, past cinemas, restaurants; we are running, breathless and oblivious to the violence brewing all around us about to engulf the city.

Now we are running as a family, in a taxi, speeding: my father tells us to get on the floor, we hear gunshots; we are careening down a deserted highway at ungodly speeds towards the airport.

Now years later I have returned to Beirut. To look for what? A beginning? An end? What possible narrative? To peer down a chasm of time: an abyss deepened by war, the ruins of a family, a gulf within the self. The civil war has created a new city yet it seems nothing has changed.

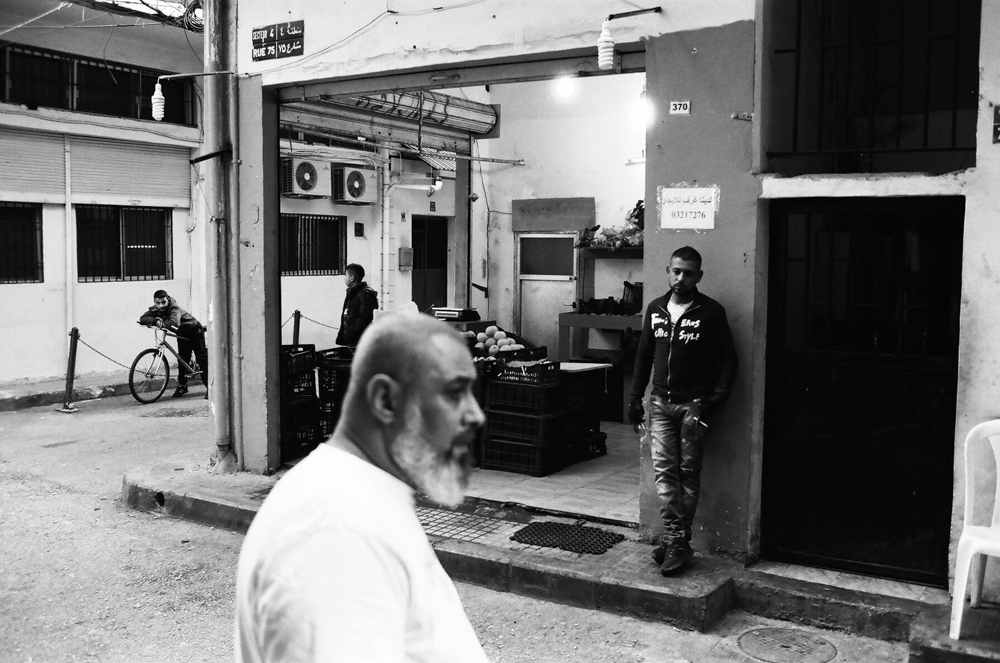

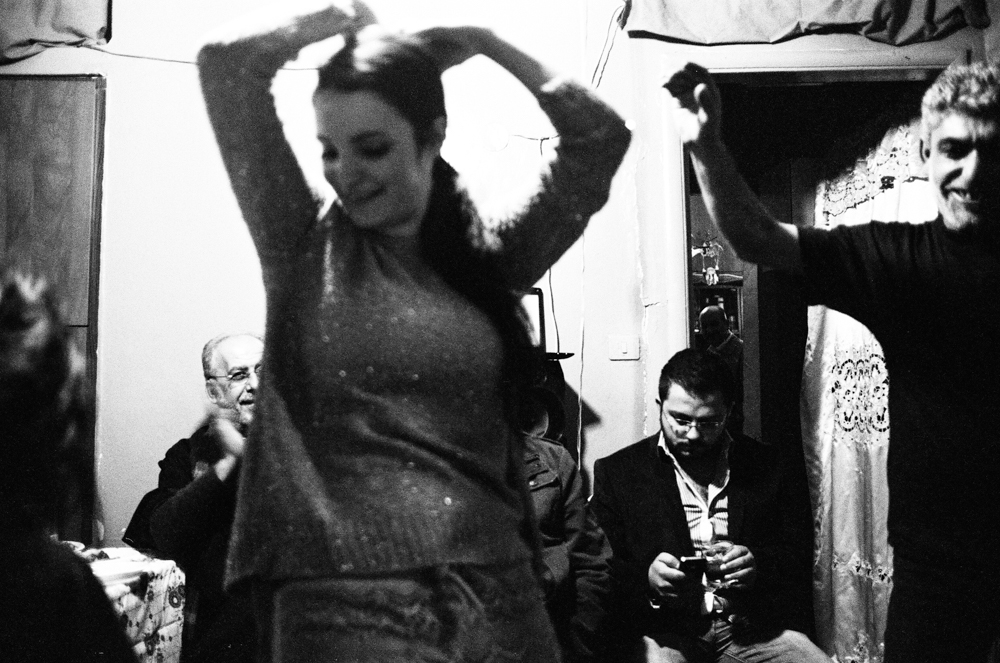

I see: narrow chaotic neighborhoods falling apart, crippled by generations of violence, external and internal; the rush of life, stench of kebab and trash, noise, dirt, wafting music and laughter. I see men, women, children, ghosts at once familiar and utterly foreign; a community, breathing and vibrant, defiant; a place, an incessant undying past.

I see: a diaspora, a community, a nation of exiles of the Catastrophe of 1915 who settled here in Beirut to re-build lives and homes; I see them here now and still: four generations on, still absorbing cascading wars, economic collapse and disasters, still connected to their far-off homelands of Western Armenia and Cilicia.

I hear a melodious resonant language—my own Western Armenian, a language on its death bed, trying to reach across an even greater abyss to its beginning; and an invisible subterranean violence that can rise like a typhoon at any moment.

I see myself.

I try to articulate a response to this space, my space and community through which I move, talk, eat, curse its history and marvel at its resilience and ability to live. I try to find a narrative. Or perhaps an end.

Ara Oshagan, 2021

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026