Rhiannon Adam: Big Fence/Pitcairn Island

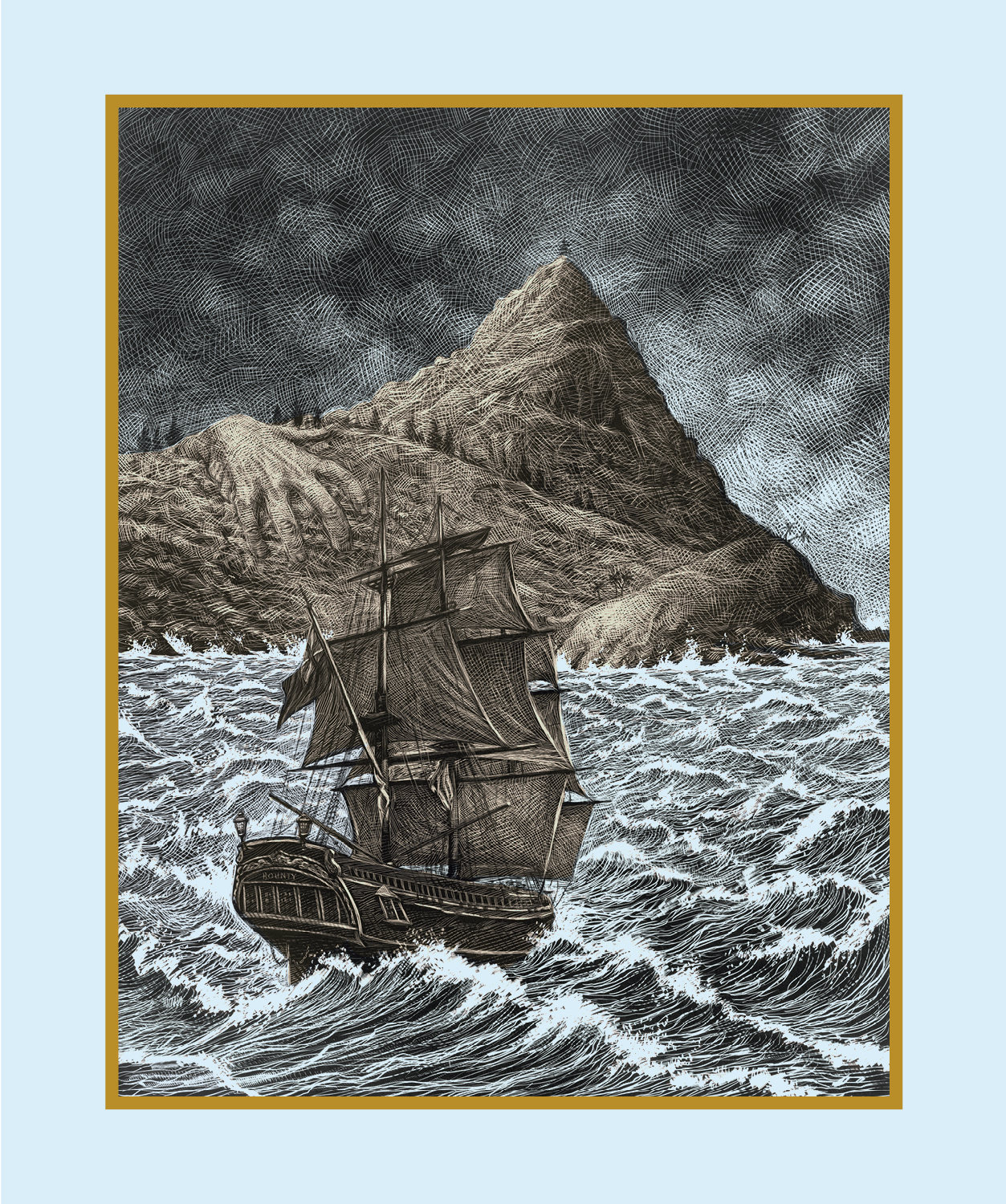

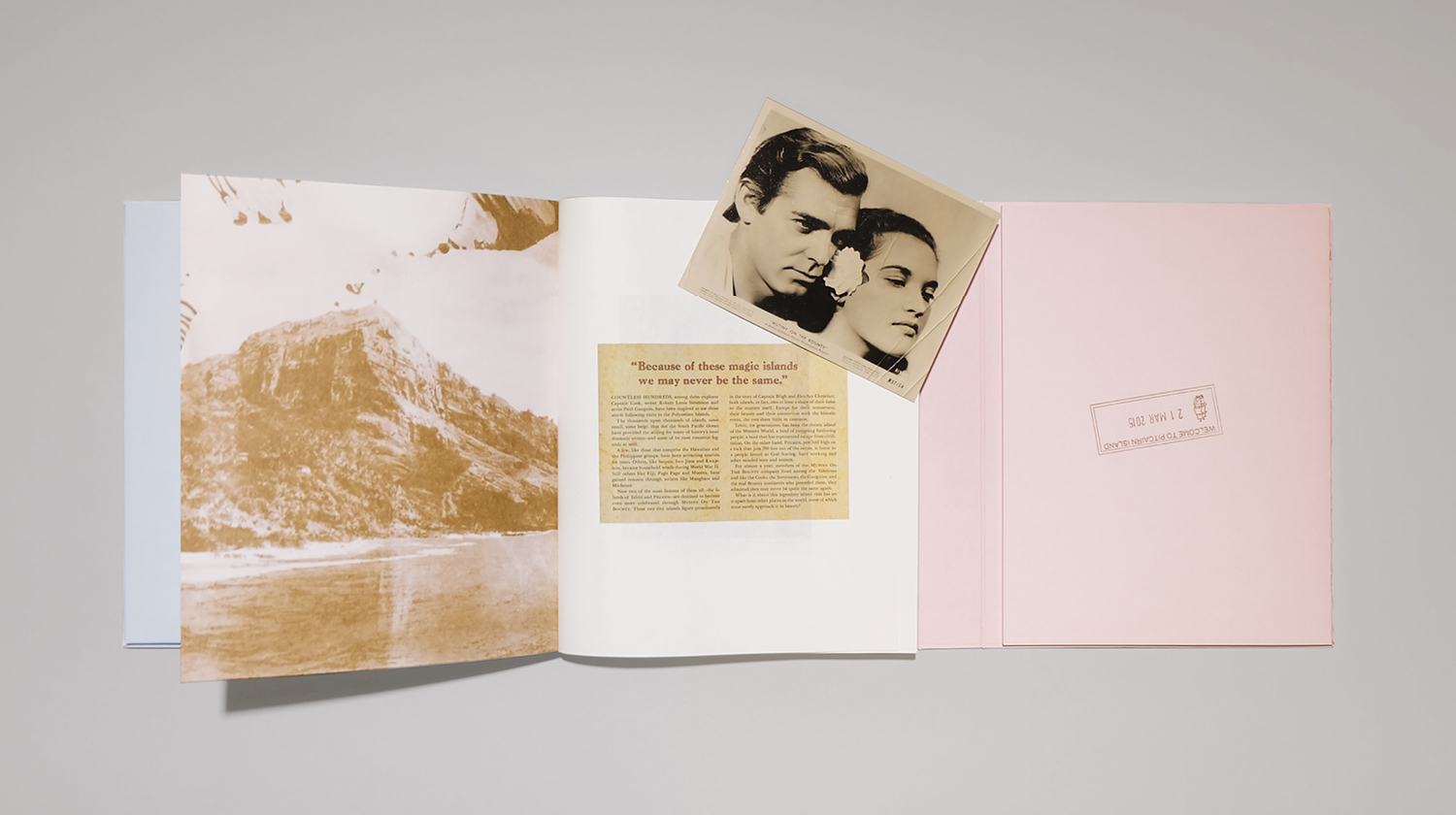

The stunningly beautiful volume, Big Fence/Pitcairn Island, is a Venus-flytrap of a photo archival narrative that lures you into the history, mystery, and allure of a South Pacific idyll only to wrench you back into the contemporary undercurrent of violence toward women, rape, and male hierarchy. Nestled beneath the romantic notion of the mutineers of the H.M.S Bounty and the later Hollywood visions of Clark Gable and others as Fletcher Christian, is the tawdry reality of how the male descendants of those mutineers evolved. Rhiannon Adam paints a startling picture of both the beauty of the geography of the South Pacific in juxtaposition with the free-wheeling domination of the sexual mores of a sub-culture by key male players descended from the Bounty mutineers.

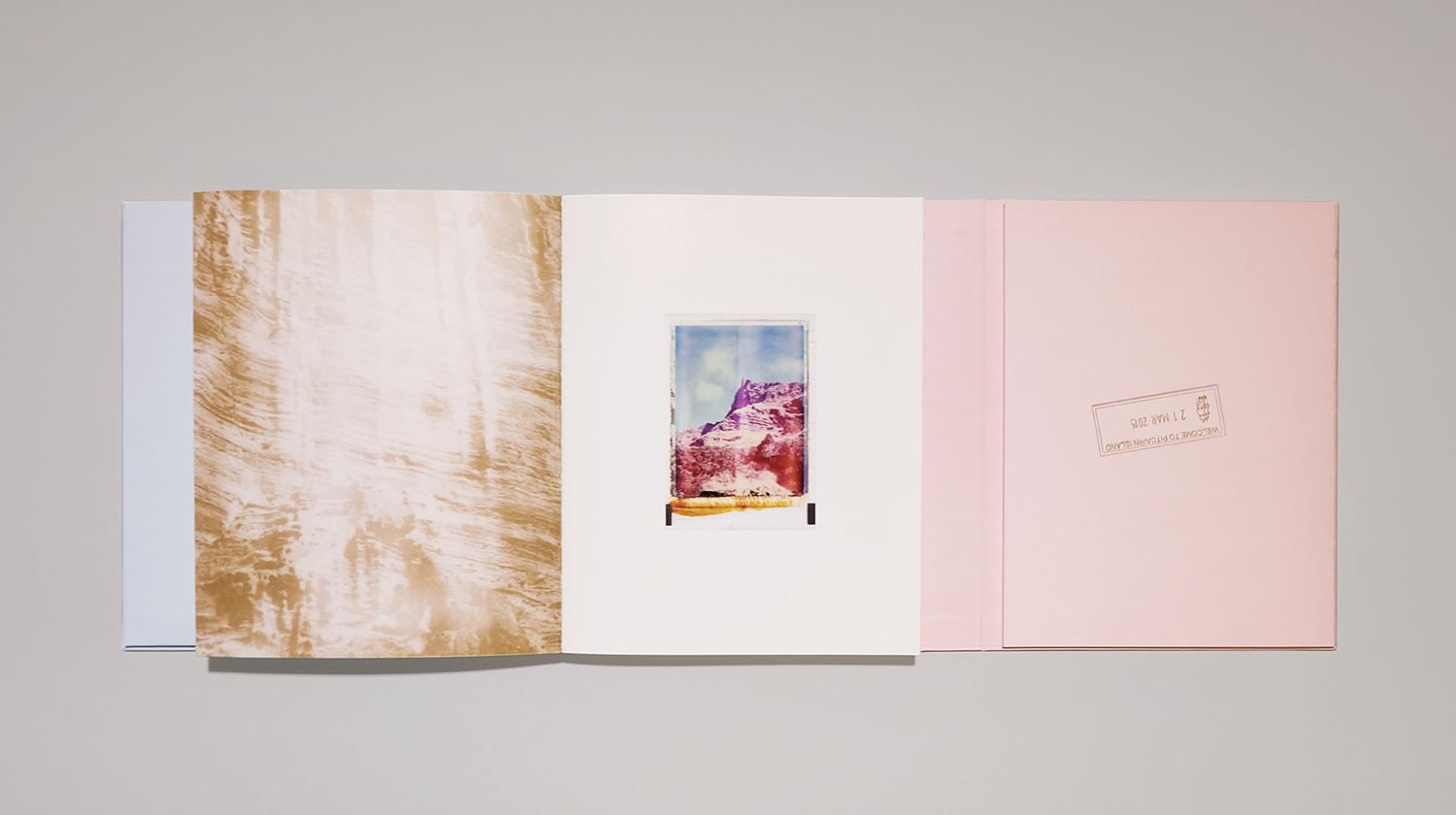

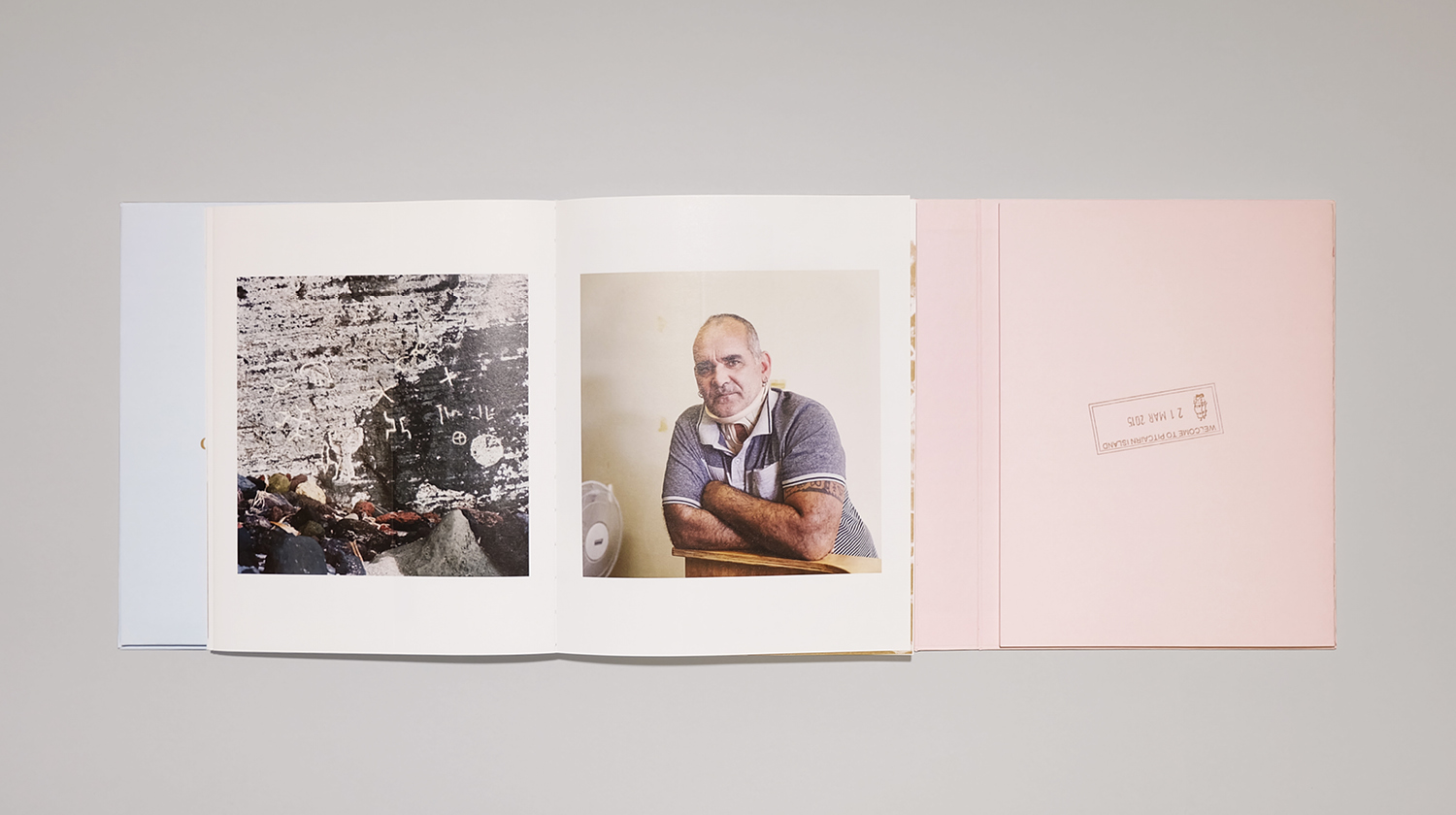

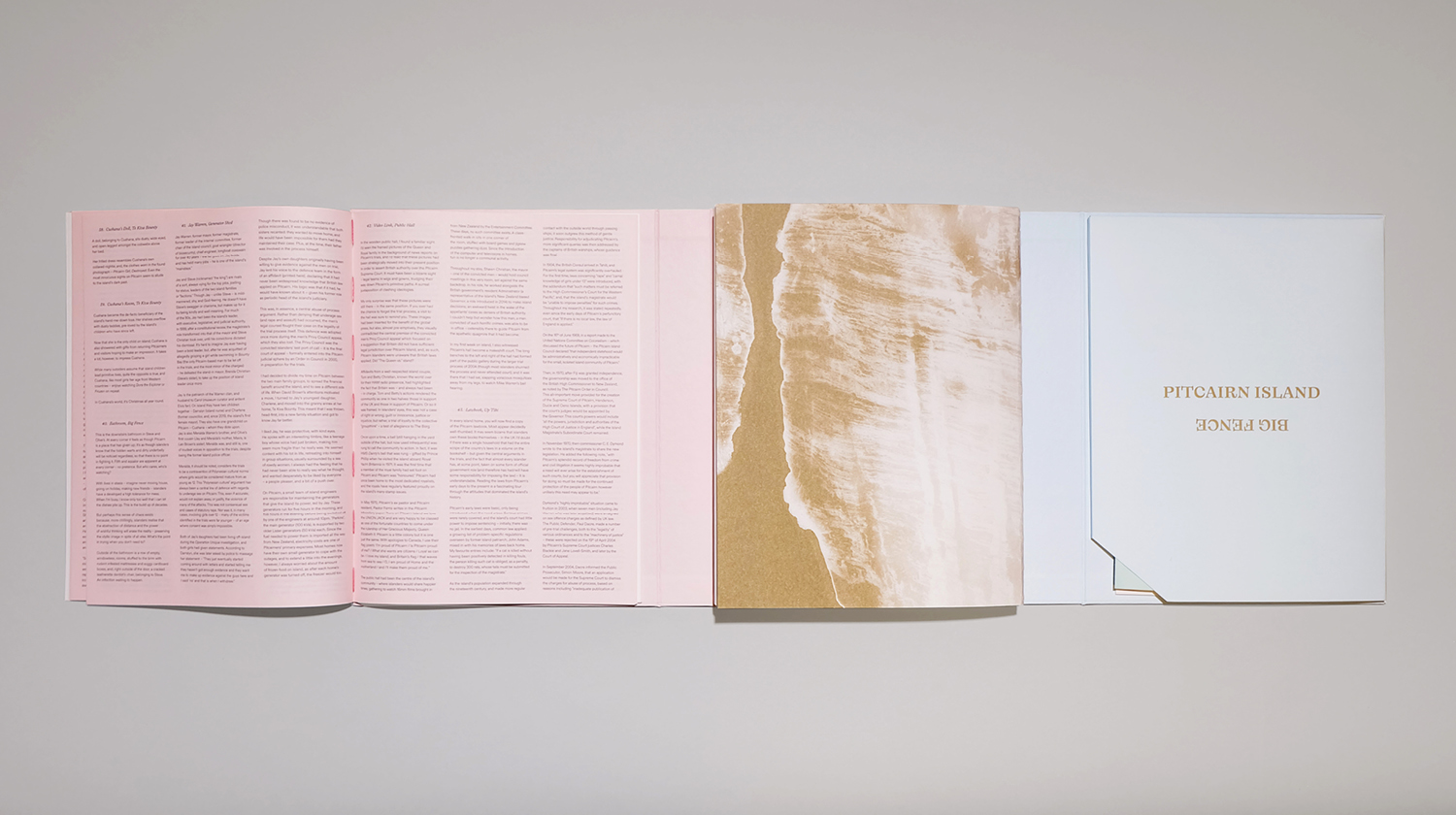

The tome is divided into two distinct inverted covers that symbolically foreshadow the divisive nature of the tale that Adam tells. As she states in her introduction, “This book is meant to be confusing, a little hard to handle, a little overwhelming, and a little discombobulating.” It is all those things, but well worth the minor inconvenience of figuring out all the pieces of the mystery and delving into the shocking tale that she weaves with the threads of legend and reality.

©Rhiannon Adam, “Sitting high above the Landing at Bounty Bay is the perfect place to watch for passing ships. On island I spent much of my time there, gazing beyond the small strip of Adamstown buildings; scanning the horizon in hope of newcomers – hungry for news and fresh conversation. Adamstown is named after John Adams (aka Alexander Smith), the last remaining mutineer to survive on Pitcairn Island. The mutineers’ early settlement was characterised by bloodshed (fights over the Polynesian women), drunkenness, accidents, and ill-health. By 1800, only Adams remained. After Pitcairn was rediscovered by Captain Folger on American whaler, Topaz, in 1808, reports made their way to England, describing the idyllic society of which Adams was then the leader. He was eventually pardoned for his role in the mutiny, avoiding the fate of several of his shipmates – hanging. When I first landed on Pitcairn, in the chaos of arrival day, several islanders asked if I was any relation to Adams, whether I was a Bounty “descendent.” I clarified by pointing out that my name lacked an all-important ‘s’ at the end, and I was no relation. But, I added, “John Adams was born in Hackney, east London, and I live in Hackney. In fact, a council housing block sits on the site of his birth, called Pitcairn House – I pass it on the bus all the time!” – they were disinterested, or perhaps didn’t feel that this was a fitting-enough tribute to their beloved forefather. Ship’s Landing had been used as a kind of lighthouse – in days past, islanders would stand there on shifts waving a lantern to guide and warn. These days, Pitcairn is off the main shipping paths, and visitors are seldom. When boats do arrive, they are announced on VHF Channel 16, and provided with landing instructions. The only lantern lit at Ship’s Landing during my stay was a symbolic beacon, created to celebrate 70 years since VE Day (though Mayor Shawn Christian mistakenly announced it over the radio as 100 years).”

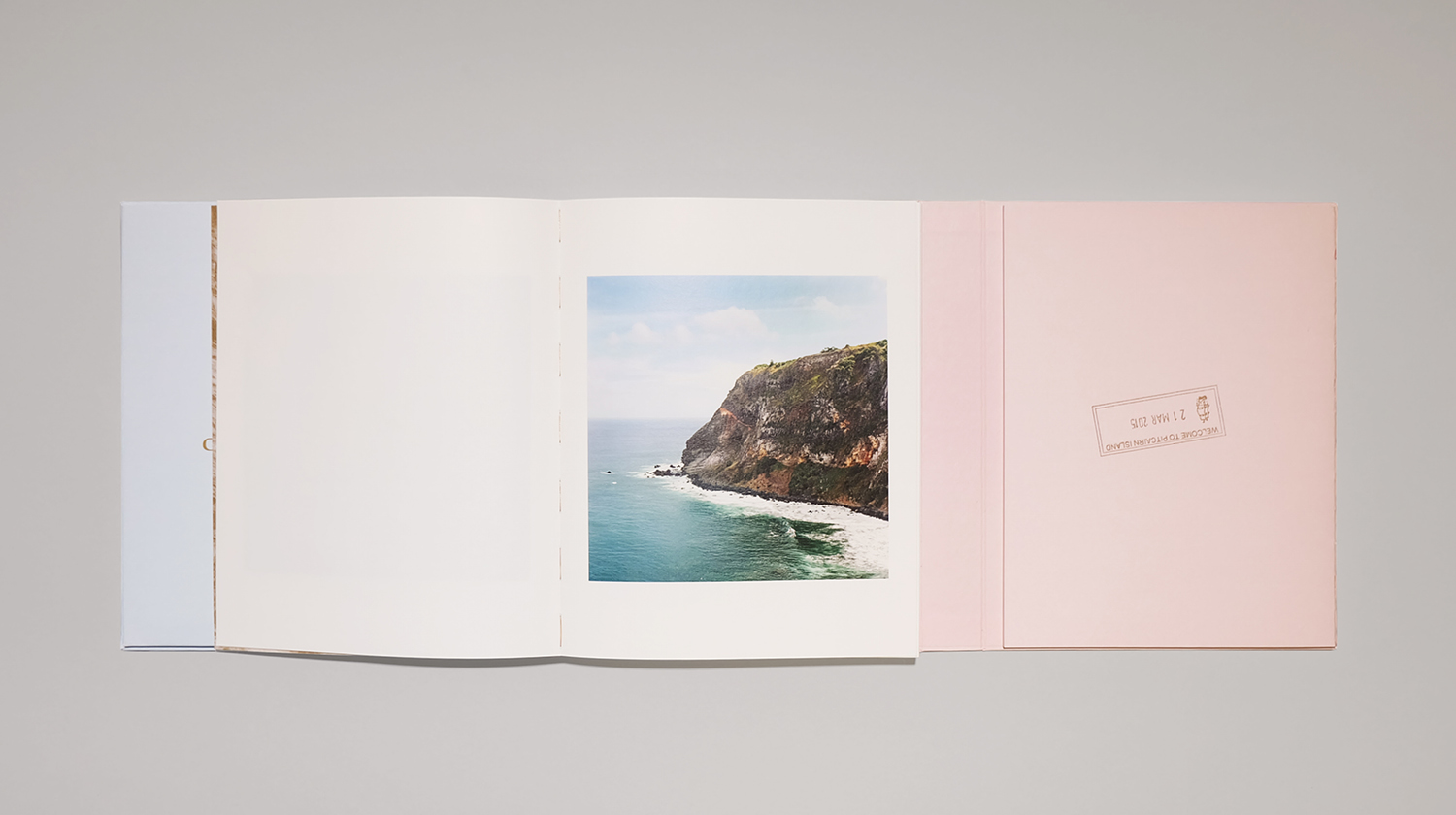

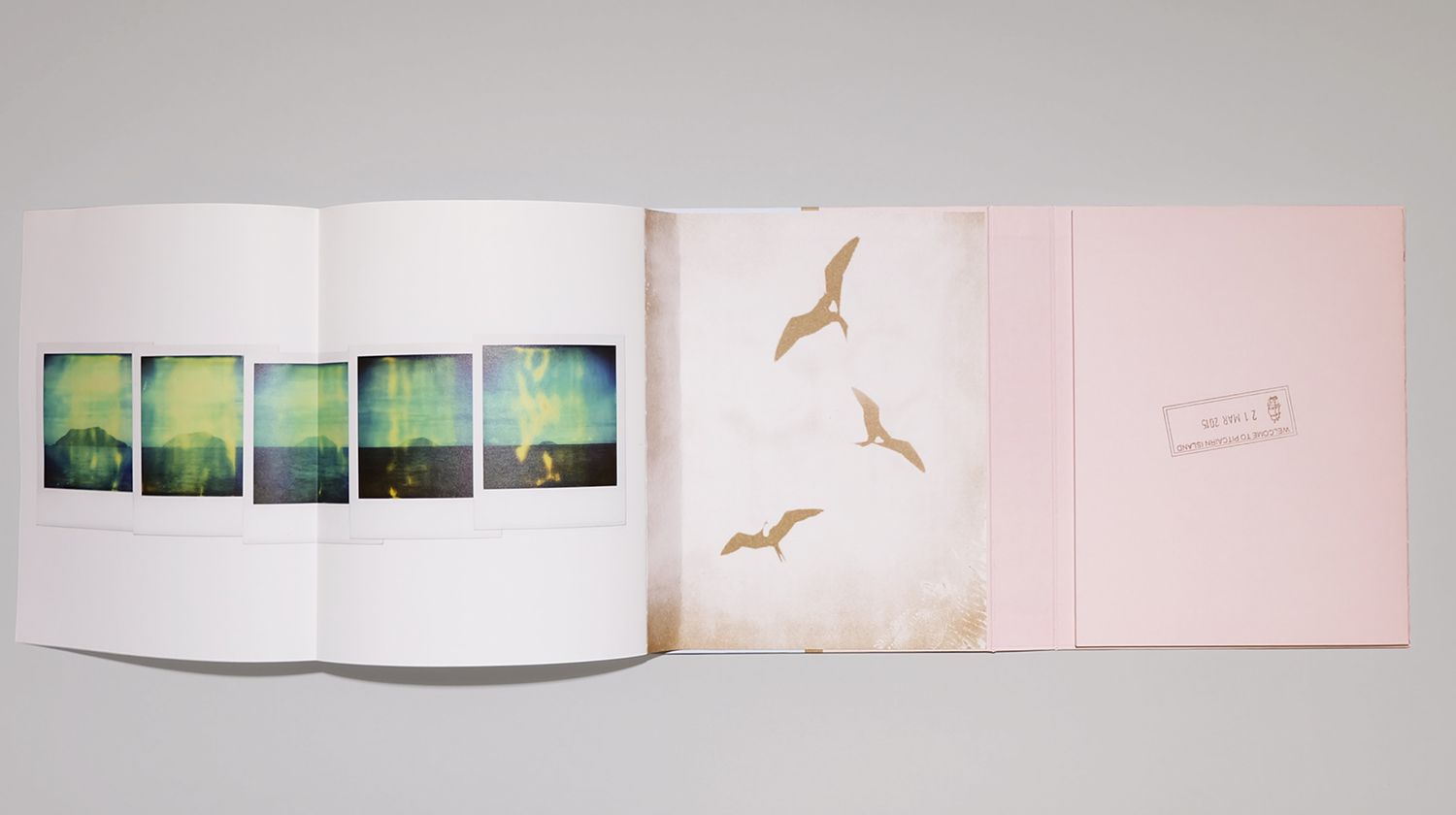

Adam spent three months on Pitcairn Island in 2015 armed with a Polaroid camera and the remaining expiring film she wanted to employ on a worthwhile project. Having had extensive experience since childhood with her adventurous family in the South Pacific, she decided to devote her efforts to the small community of Pitcairn Island. Gem Fletcher’s enlightening introductory essay sums up what transpired next: “Through a potent combination of photography, archive, text and interview, Rhiannon does the complex work of animating how violence can coexist with care, and trauma with liberation. What began as a project about the notion of utopia on one tiny, barely populated island in the Pacific, morphed into a study of power, our complicity in the fetishization of white male revolutionaries, and how their vision replicates the very inequalities that they rebelled against.”

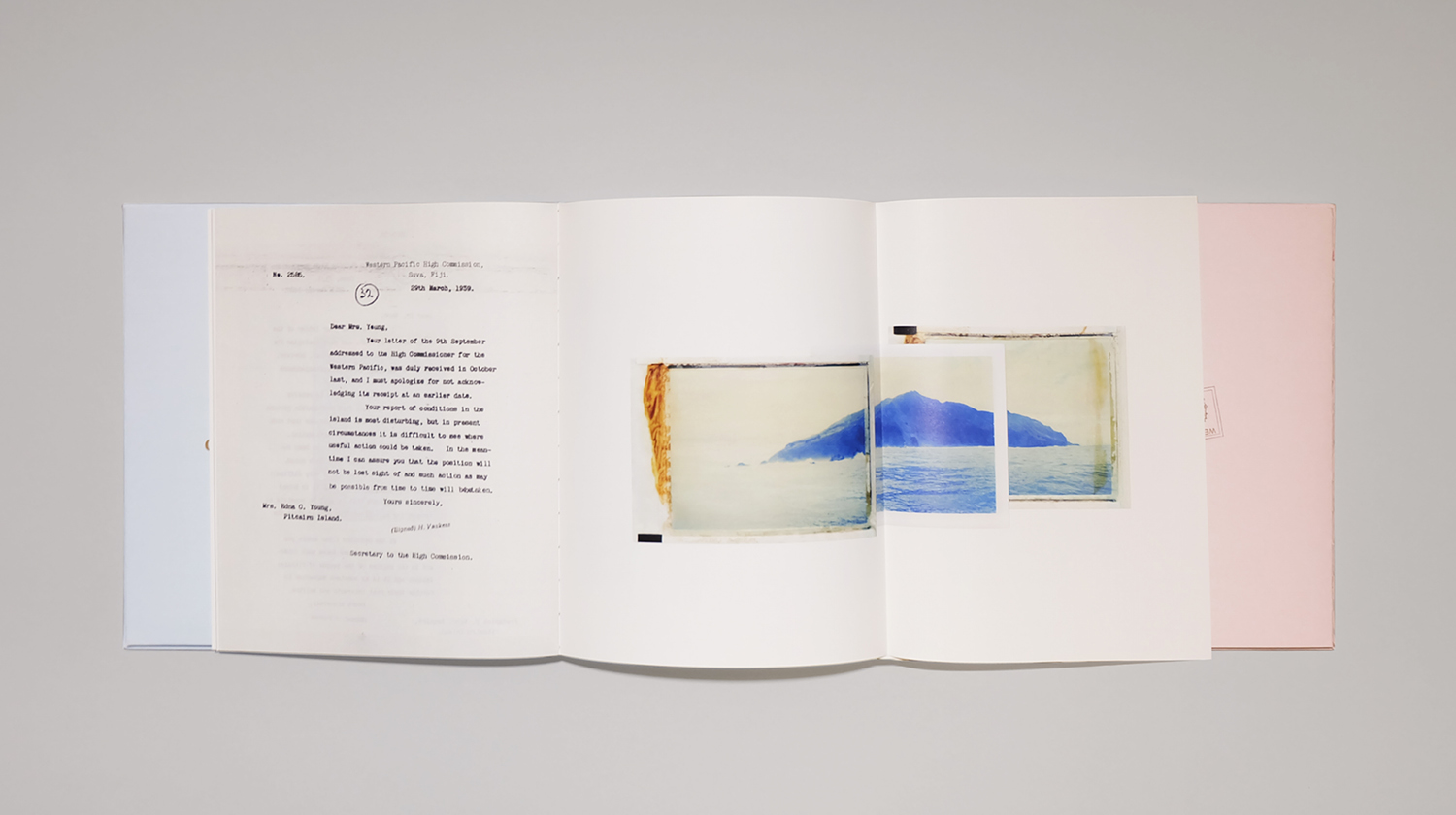

Adam’s initial idea was to make portraits of all the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island (47 as of early 2020), a British territory in the South Pacific, in order to create a lasting record of the place at that moment in history. She arrived on the island well informed about the series of sexual assault and rape trials that had occurred roughly twelve years prior whereby half of the island’s adult male population, including several of the island’s leaders at the time, were convicted based upon testimony by various women who had left the island. What has evolved in the book is a divergent array of archival material including partial transcripts of the trials, paraphernalia depicting various movies and images of the alluring South Pacific, actual Polaroids and other photos of Pitcairn islanders and the island today.

©Rhiannon Adam, “Cushana, Pitcairn’s only child, waits for the frigatebirds that circle the landing with detritus from the day’s catch, feeding the giant birds by hand. When they swoop down, they appear bigger than her. More like pterodactyls than birds. A storm was brewing, and a wall of rain was quickly approaching from the sea. As the wind was picking up, Cushana’s joyous yelps vanished with the gusts. I watched her shiver with excitement and wait for the right moment to let go, just as the frigate had successfully grasped its prize. Watching Cushana and the frigates reminded me that here we were, at the intersection between man and nature. It is impossible to divorce the Pitcairners from their rock – the two are inextricable. The isolation and rugged landscape are as coarse as the personalities and attitudes of our living characters, as though they come from the pages of a book. It is as if their geographical location is a device, or a literary construct. Sometimes the parallels between the island and its people can seem “too neat” a metaphor, but the intermingling of fact and fiction are Pitcairn’s reality. In hindsight, this image took on a new significance as a representation of female defiance. Pitcairn is in Cushana’s hands now, as she is the next generation. It is up to her to change the narrative, to chart a new course.”

The Big Fence of the title has several factual and symbolic meanings that include: the house where Steve Christian (one of the convicted leaders of the community and a direct descendant of Fletcher Christian of H.M.S. Bounty fame or infamy) and his wife, Olive, live and is the first home you encounter upon arriving on the island; the house name directly associated with the “trials” as many of those convicted were locally known as “the Big Fence gang”; the symbolic boundary of the book between fiction and reality; and finally, the island and the greater vast wall of the Pacific Ocean. These multi-faceted symbols shine through as one pages through the constant contradictions of grass skirts, dramatic landscapes and powerful transcripts from the sexual assault trials.

On a final note, the book soars from a visual point of view by the meticulous attention to detail in the design and innovative construction of the object by Rhiannon Adam and designer, Aneta Kowalczyk of BlowUp Press. The tome is an organized maze of maps, captions, essays, and an index that lead you through the labyrinthine story that Adam tells with such clarity and sympathy.

This is a book to appreciate for its artistry and daring in bringing further light upon an issue that is not confined to a remote island in the South Pacific. It presents an unusual case study in yet another tale of masculine overreach and domination that should no longer be condoned in any environment.

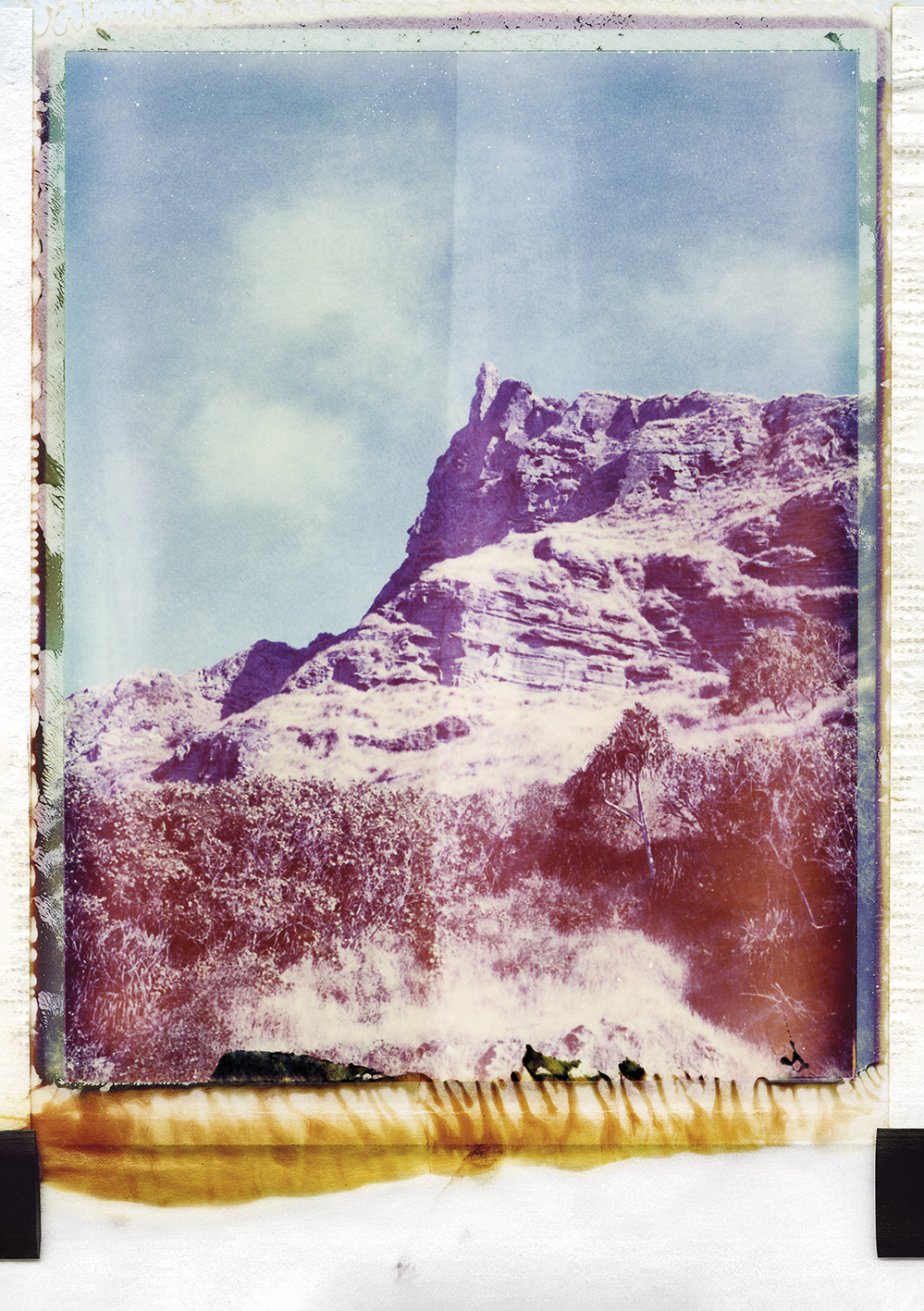

©Rhiannon Adam, “When most think of the South Pacific, images of swaying palm trees and glistening strips of soft white sand immediately spring to mind. Pitcairn bears little resemblance to that vision. It is rocky and volcanic, emerging abruptly from the vast blue horizon, as if by accident. It was here that the Bounty’s mutineers made their home, finding – in this most austere of islands – the perfect hiding place. Its inaccessibility providing a veil of secrecy, resulting in both its protection and subsequent decline. When I arrived on Pitcairn, I was handed a crudely drawn map of the island, and was quick to notice that its craggy shoreline was littered with tragedy-laden place names: Oh Dear, Dan Fall, Nellie Fall, Lin Fall, McCoy’s Drop, Six Feet – to name but a few. While on island, and particularly in my early days, when hostility and daily showdowns had become a part of my everyday existence, I couldn’t help wondering if I too may end up with a “drop” named after me, should I make a proverbial (or literal) misstep. I wasn’t the first to have thought this – in October 1952, Freda Gwilliam, Education Adviser to the Colonial Office, wrote a report about the state of Pitcairn Island, based upon correspondence received from Mrs Moverley, wife of Pitcairn’s first government-appointed teacher Albert Moverley. In the report, she summarises Mr and Mrs Moverley’s fears regarding the island’s chief of police, Floyd McCoy, who had recently been banished to Tahiti. She writes, “the old gang have everything lined up for him on his return. Their previous experience of the covering-up of crime under the umbrella of accident makes them fear for his life, which sounds melodramatic, but which from their experience they feel is very likely.” If this were even a perceived risk to an islander, I felt that my own fears were somewhat justified. A closed community like this one was likely to protect itself, to close ranks, at all costs.

Adam’s work is heavily influenced by her nomadic childhood spent at sea, sailing around the world with her parents. Little photographic evidence of this period in her life exists, igniting an interest in the influence of photography on recall, the notion of the photograph as a physical object, and the image as an intersection between fact and fiction – themes that continue throughout her work.

Her long-term projects straddle art photography and social documentary, while subject matter is often focused on narratives relating to myth, loneliness, and the passage of time. The results of these explorations are captured almost exclusively in ambient light through the hazy abstraction of degrading instant-film materials and color negative film, and are often contrasted with the stark reality of archive material.

As a part of her varied practice, Adam is also an occasional publisher and curator. Her imprint ‘Lost Cat’ was founded in 2013 with the release of Kevin Griffin’s Omey Island: Last Man Standing, and until 2015, she was the resident curator and co-founder of Gallery One and a Half, a photography gallery in Hackney, London.

Her work has been exhibited internationally as well as being widely featured in the press –including the New York Times, M Magazine/Le Monde, Art Review, The Guardian, The Telegraph, Huffington Post, BBC, Vice, Huck, Featureshoot, The British Journal of Photography, Fisheye, It’s Nice That, Dazed and Confused, Colors magazine, Harpers Bazaar and Loose Associations (published by the Photographer’s Gallery).

©Rhiannon Adam, Before you saw her, you heard her. Her lilting Pitkern twang was peppered with accentuated intonation, shaky and slightly lisping, where her ill-fitting false teeth had become loose. At points, her voice pierces the air, vacillating between the austere British accent of a 1900s governess and the projection of a priest, flowing in a sing-song of birdlike chatter. She was rarely quiet, talking to herself when no one was around, occasionally bursting into song. Her laugh was rapid, and erupted in bursts – a kind of high-pitched mischievous cackle; carefree… as indulgent as treacle. Blight, her island nickname, must have been ironic, for these days, Irma was all love, all abundance. She smiled with her whole body, as though every bone in her skeletal frame had suddenly become childlike again. She was so slight that the beaming grin on her face seemed to be 50% of her body mass. I was amazed that she could be so small and still breathe, walk, and function. She wore jogging bottoms and a sweatshirt every day, usually in mismatched bright block colours – hot pink, aqua, electric blue. Like someone from an 80s exercise video about to spring into action. Though she was now frail, she fizzed with a kind of frantic energy. Here she is peeling ‘wild beans’ – a Pitcairn staple that even most islanders dislike. Her fingers as knobbly and gnarled as the beans themselves. Irma told me stories about going to Buckingham Palace – “have you been, dear?” she asked, with genuine interest. “No”, I said. “Oh you must. London is divine.” As a Londoner myself, it seemed surreal to be having such conversations with an elderly Pitcairn Islander. To me, the palace was completely out of reach, but of course – Pitcairners were different. Due to their small number, official visits and tours became part of most island roles, and many of the once-important people on island had spent a few minutes with the monarch. I think they thought that everyone had had the same experience.

©Rhiannon Adam, Brenda Christian is Steve’s younger sister. She lived off-island for many years, having originally married Michael Randall, a Welsh RAF technician who had been stationed on Pitcairn to monitor the impact of the French nuclear tests in the region in the early 1970s, eventually raising a family together in the UK. She has one child on island, her only son, Andrew “Little ‘un” Randall, Pitcairn’s only gay man. Andrew was the first baby to be born on island in over a decade, and Brenda had made the trip back specifically to give birth. It was while she was working on an army base in the UK, that she met her second husband, Mike Lupton, an affable British divorcee with piercing blue eyes, who worked as a retail manager for the army. Before they married, Mike Lupton had – in secret – double barrelled his surname to Lupton-Christian by deed poll. When he and Brenda married in 1997, he “gave her the name back as a wedding present.” In 1999, Mike and Brenda moved to Pitcairn. Almost as soon as she arrived on island, Brenda’s life took a turn, and she found herself – for the next several years walking on eggshells – attempting to do her job as island police officer – and in the process, breaking her family apart. It was Brenda who had had to arrest her own brother, and Brenda who had to sit in court listening to every scrap of harrowing evidence. Brenda knew the “what, the where, and the who” and “had to keep it a secret for four long years.” Steve and Brenda are now back on speaking terms, but they are not close – to this day they represent the deep rifts that transformed families – and the island – forever. Brenda still serves as the island’s community police officer, a job that through Pitcairn’s history has been both thankless and difficult. It is, of course, challenging to police small communities, but even harder when you are part of that community yourself as crimes are rarely reported.

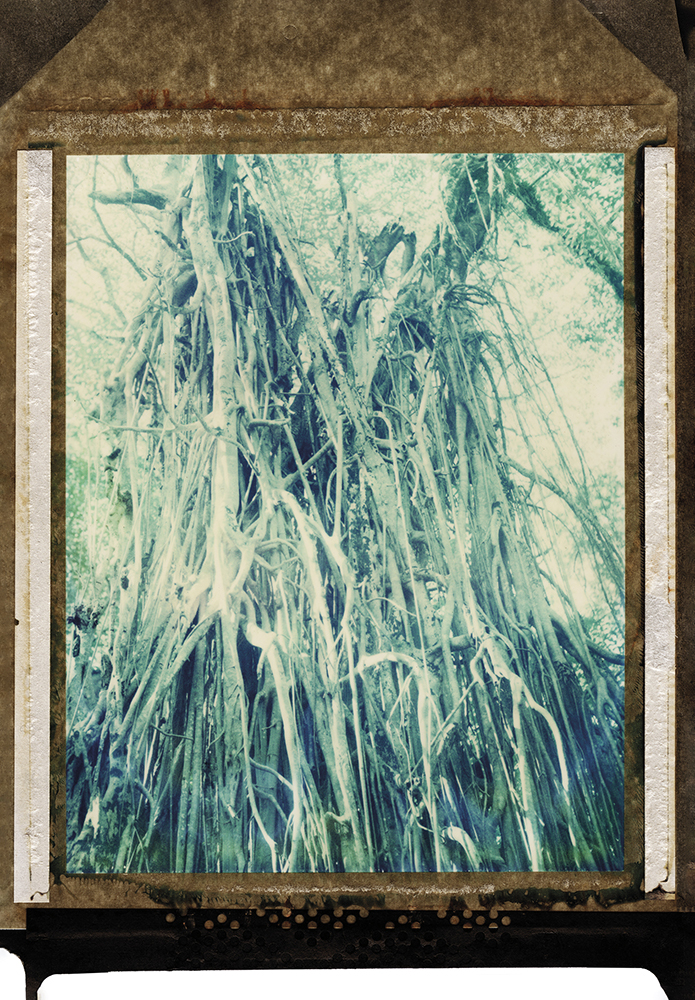

©Rhiannon Adam, These spindly fig trees occupy the far corner of Adamstown. Their fronds hang like Rapunzel’s hair, layered into a tangled web; beautiful, and yet sinister – like something from the Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I would pass them on the way to Pulau school, or to Down Flatcher. A shaded nook with a mystical quality. In the past, children would swing from these tendrils, emulating Tarzan. Today, they hang silent. Inanimate. There are no children here to play now. In the 70s, Steve Christian raped a twelve-year-old girl amidst the banyans. The girl had been walking with a group of friends when Steve and a gang of boys grabbed her and forced her to the floor. They removed her shorts, and Steve raped her, while the others held her arms and legs. When he was finished, he encouraged the others to “have a go” – a familiar pattern, one repeated by his sons two decades later. I had seen Steve speed around the corner at Jack Williams Valley. It had become a storage area for heavy machinery, some of which Steve was the only person licensed to drive. I wondered if he considered the significance of the place, or even cast his victims a second thought. Whether the positioning of where the vehicles were parked was a kind of protest – a suggestion that despite his convictions and the legacy of his crimes, he was still “top dog”.

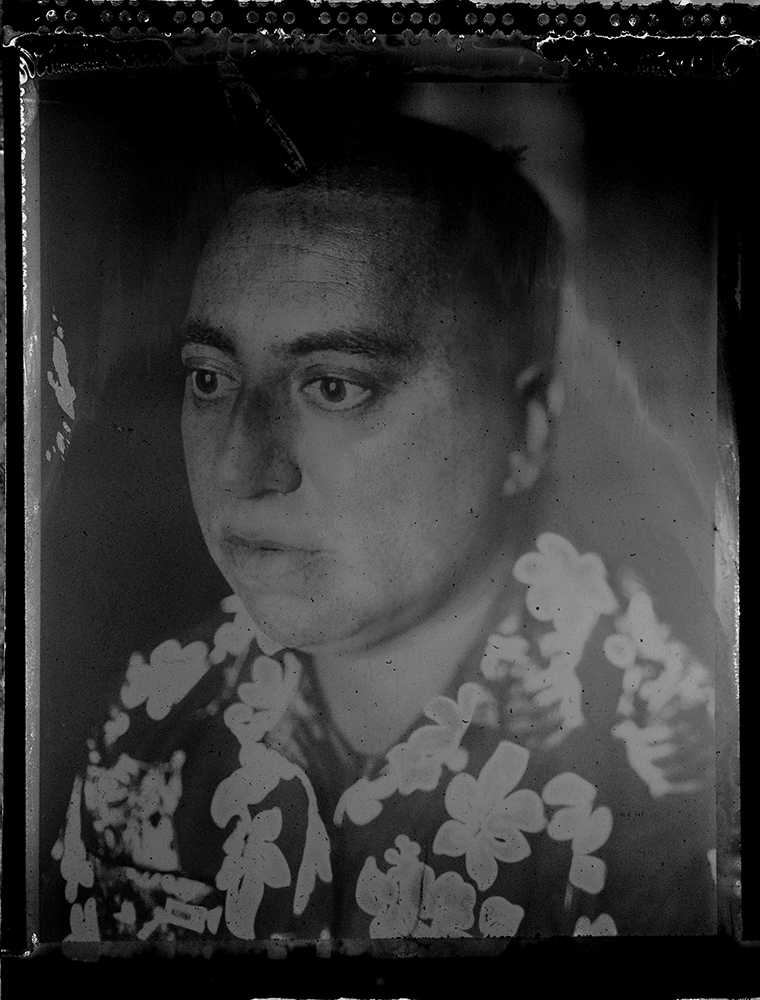

©Rhiannon Adam, Shawn Brent Christian (39), direct patrilineal descendent of Fletcher Christian (leader of the Bounty mutineers), sits in the public hall, the site of the irregular council meetings that he presided over as mayor. Pitcairn’s scandal may never have come to light were it not for Shawn Christian. In 1996, a visiting Adventist pastor reported to Kent Police that his daughter (11) had been raped by Shawn Christian, then 20. Two Kent police officers, Dennis McGookin and Peter George were dispatched to Pitcairn to investigate. Though they found insignificant evidence to lay charges, they found a virtually non-existent legal system and ineffective policing. In case something were to happen, Pitcairn would be wholly unprepared. They suggested to the British authorities that there should be a full-time police officer on Pitcairn – this proposal was, unsurprisingly, rejected, given the cost. Instead, Kent police sent a colleague, PC Gail Cox, to train an island police officer for three months at a time, every other year. Cox was instrumental in the lead up to Operation Unique. Eventually, Shawn saw justice brought against him for a different case, when was convicted of two rapes and one count of aiding and abetting a rape in the Pitcairn Supreme Court, sitting in Papakura, New Zealand. Shawn’s conviction followed on from his brother Randy’s conviction for the same crime, only his brother’s case had (a few years prior) been heard in the makeshift court room that had inhabited the very-same public hall where Shawn now sits. Shawn had been 31 at the time of his trial in 2006–2007, and as I took this image, he was approaching 40. At the time of his arrest, Shawn had been living, working, and studying in Australia, and was married to an Australian woman, Michelle, a blonde hairdresser, who, like all the Pitcairn wives, had stuck by her man. She now lives on Pitcairn with him, and her Pitkern twang imbues her nervous speech.

©Rhiannon Adam, Cushana, aged six (b. 2009). Cushana was the only child living on Pitcairn Island during my stay. She is the youngest of Charlene Warren and Vaine Peu’s five children. Her elder siblings had all left for boarding school in Palmerston North, New Zealand – Pitcairn’s own school system ends at 15 – and Cushana now ran the roost. Cushana is ferried to and from Pitcairn’s school, Pulau, daily by the island police officer, Brenda Christian (who has held the role since 2001), or by her mother, Charlene (who became the island’s mayor in 2019). Charlene was one of the original complainants in the trials, but later withdrew her statement when she returned to live on Pitcairn. Cushana has a “safe adult” list, and is instructed to associate only with those included. On an island of just 42 (in 2015), Cushana’s contact list is limited. At no time is she allowed to wander unaccompanied, and she is never left alone with island men. Her childhood is very different to that of the older Pitcairners, who describe a youth with few rules and absolute freedom. But it seems that that their freedom had come at a price. If Cushana’s world is limited by the ocean that encircles the island, her lifestyle is dictated by the apparent threat of her neighbours. When she grows up, she wants to travel to London, see snow, and meet the Queen.

©Rhiannon Adam, Kevin Young burns the remaining personal belongings and documents found in Brian and Kari Young’s former home. A contained fire smokes, emerging from an empty oil drum in the yard of Up Tibi – the house that Kevin has just bought from them for $400. Pitcairn’s real estate market isn’t exactly thriving. Smoke hangs between the palms on a still afternoon, the air thick and weighty. A purge, a cleanse, but the glowing embers fight to survive, the psychological heaviness surrounding the fire’s tinder refuses to be extinguished. On Pitcairn I often felt that I was looking through a cloak of smog, trying to decipher the details. Somehow, this image seems to sum up my island experience: everything in front of me, yet concealed from view – slightly obscured. Quite literally smoke and mirrors

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Ian van Coller: Naturalists of the Long NowApril 22nd, 2024

-

Earth Month Photographers on Photographers: Tyler Green in Conversation with Megan JacobsApril 15th, 2024

-

Shari Yantra Marcacci: All My Heart is in EclipseApril 14th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Cansu YildiranMarch 29th, 2024

-

Broad Strokes III: Joan Haseltine: The Girl Who Escaped and Other StoriesMarch 9th, 2024