Daniel Seth Kraus: Plain Ordinary Working People

Daniel Seth Kraus‘s work blends historical research with photography to deepen our understanding of people, places, and how they combine to create a culture. In practice, Kraus strives to create work which is informed and empathetic towards the subjects and his viewers. While maintaining his own artistic practice, Kraus is also working in collaboration with Byron Wolfe on two extremely rare microphotographs made by 19th century photographers, the Langenheim brothers. Kraus writes on photography and contemporary photographers for Pellicola Magazine, and publishes videos of photobook reviews on his youtube channel, The Photobook Review.

Kraus earned a MFA (2017) in photography at the Tyler School of Art & Architecture at Temple University and also holds a BFA in Photography and BA in History from the University of North Florida (2013). Having a background and training in historical research has greatly influenced the way he approaches creative projects. His work has been featured in numerous print and online publications, including Esquire Russia, Fraction, SeeSaw, Oxford American, Create Magazine, Aint-Bad, and Ruminate Magazine. His photographs have been exhibited in national and international juried exhibitions including South Korea, China, and Ireland. Kraus was the 2016 recipient of the College Arts Association’s Professional Development Fellowship in Visual Arts grant and was awarded a fellowship by the John Teti Rare Photography Book Collection at the Institute of Art & Design at New England College for his self published books and research on the practice of “participant observation” in contemporary documentary photography.

Kraus currently lives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he teaches courses in photography, video, and the history of photography, at Tyler School of Art & Architecture, Pennsylvania College of Art & Design, and The College of New Jersey.

Plain Ordinary Working People

“There’s absolutely no limit to what plain, ordinary, working people can accomplish if they are given the opportunity and and the encouragement and the incentive to do their best.” -Sam Walton, Wal-Mart Founder

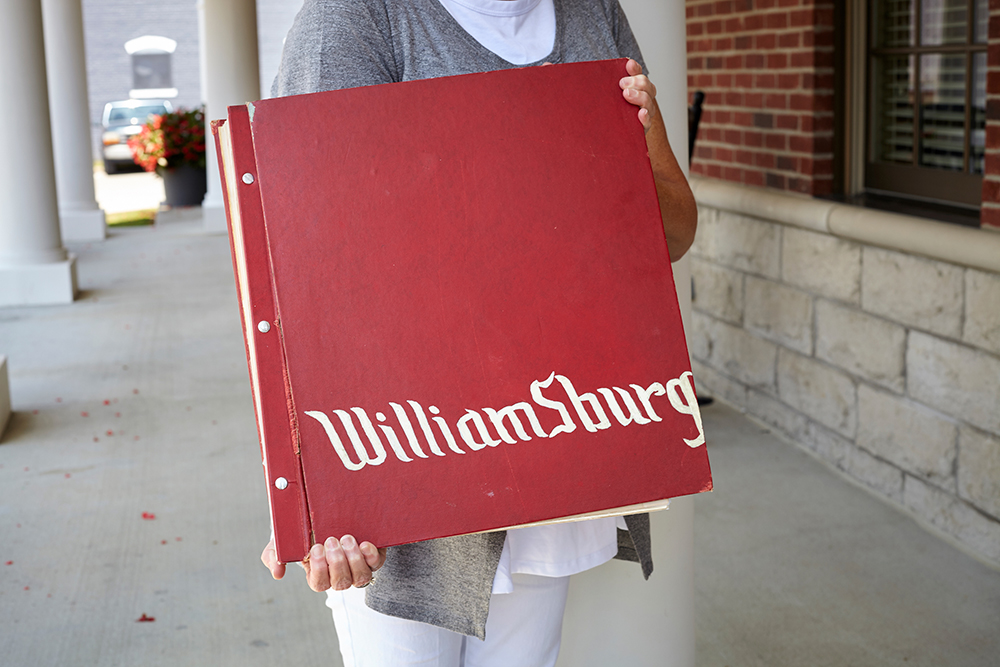

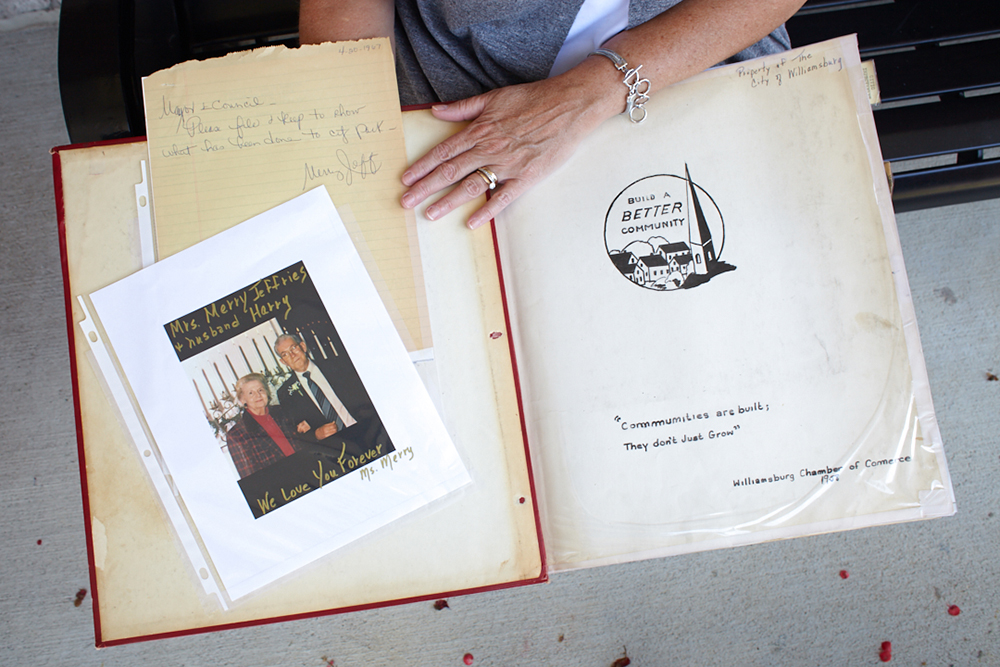

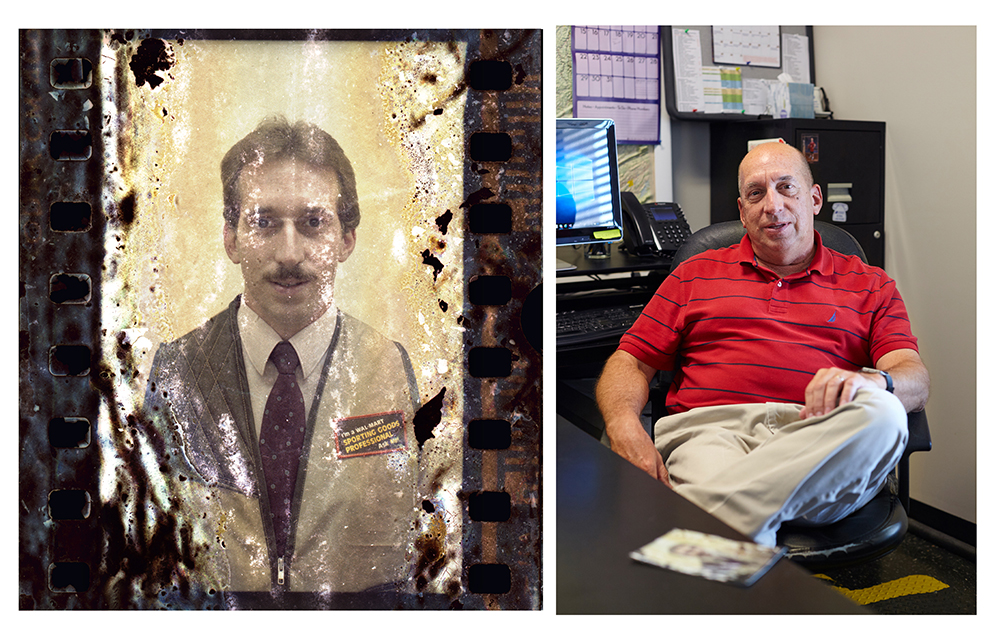

Plain Ordinary Working People is a photographic project that reveals the connections between a small town, lost negatives, and Wal-Mart. In 2012 I found a sleeve of negatives on the floor of a log cabin home in Williamsburg, Kentucky. Upon scanning the negatives, I discovered they were portraits of Wal-Mart employees. Initially, the deteriorated images sparked questions about their origin, the identity of the subjects, and how they arrived at the cabin. Over the course of four years searching newspaper archives, making phone calls, and writing letters, I located 5 of the employees–Janice, Tina, Chet, Audrey and Jim,—who helped answer some of my initial questions, 30 years after the original portraits were made. After interviewing them and making new portraits, the personal stories they shared contrasted with the sterile images of them as employees. People, places and companies in small towns have dynamic and complicated relationships which both benefit and harm one another. Using the negatives as a source, the project sheds light on the time, place, and sociological environment the negatives captured during that 1986 summer in rural Kentucky when Wal-Mart came to town.

©Daniel Seth Kraus, Manager’s Office Featuring Portraits of Sam Walton and Store Employees, Williamsburg Kentucky

Marisa Lucchese: Tell us about the landscape of your growing up and what brought you to photography?

Daniel Seth Kraus: I grew up in a suburban town between Jacksonville and St. Augustine, Florida but I was actually born outside of Seattle on Whidbey Island. My father was in the Navy and Jacksonville was the final stop for my family. I was introduced to photography by accident. As a freshman in high school I was placed into a new elective course the school offered for the first time and needed students to enroll into, Creative Photography. After this first class I took every photography course offered and it became the impetus for exploring and running around with friends. After graduating high school I decided to double major in photography and history, which cast the die for my creative and intellectual interests. The physical landscape that shaped my growing up was distinctively northern Florida. I’d go to natural springs with my friends from church, hangout at fish camps along the creek I grew up on, and drive around looking for pictures.

ML: You also received a degree in history. How has this influenced your artistic practice?

DSK: Studying history tremendously shaped my photography work, specifically in how I thought about the subject matter I photographed. My history professors taught a method for understanding things that might be unfamiliar to you, a way to ask questions and find answers, and how to get the bigger picture of the issue. However, I really didn’t put history and photography together until I began graduate school and the questions posed to me required responses that went beyond personal experience and anecdote. I began photographing issues that were hot-button topics in some regards, religion, labor and the environment. The research methods I learned studying history helped push my work outside my experiences and draw from a wider range of knowledge to incorporate into my work. In short, my photographic practice is motivated by personal inclinations and my training in history helps me to contextualize with research.

ML: How did you come to find the negatives, and what propelled you to expand the potential of your discovery? Why did you feel this story needed to be told?

DSK: While working as a camp counselor in Kentucky during the summer of 2012, I was responsible for taking them into the mountain communities to help people with service and manual labor. One specific location I returned to throughout the summer was a very old log cabin where a couple lived, Martha & Arnold. The negatives were in a sleeve on the floor amongst all sorts of things, but I saw them and instinctively picked them up to see what they were. I asked Arnold if he didn’t mind if I kept them. I scanned them in a few weeks later and saw they were old and dated Wal-Mart employee headshots. For the next several years I tried to figure out how I could use them creatively or if they were best left on their own as found images. During my first year of graduate school I was sharing the negatives with an art history professor and she asked if I’d tried to find the subjects of the photographs. Since she asked, I felt compelled to take on the challenge and see where it led. I never thought I’d get to photograph or even meet the people in these photographs, but I wanted to see where they led. I thought their individual stories and histories needed to be shared because they were personal and unique, especially compared to their employer. During studio visits people saw the Wal-Mart logo on the employee smocks and immediately wanted to talk about the politics around large corporations. I took the same interest in the work, but over time I thought the more interesting questions pertained to the subjects rather than the company. I thought story of the subjects would be more interesting than the logo.

ML: How difficult was it to find the people in the images, and what did they think about your project?

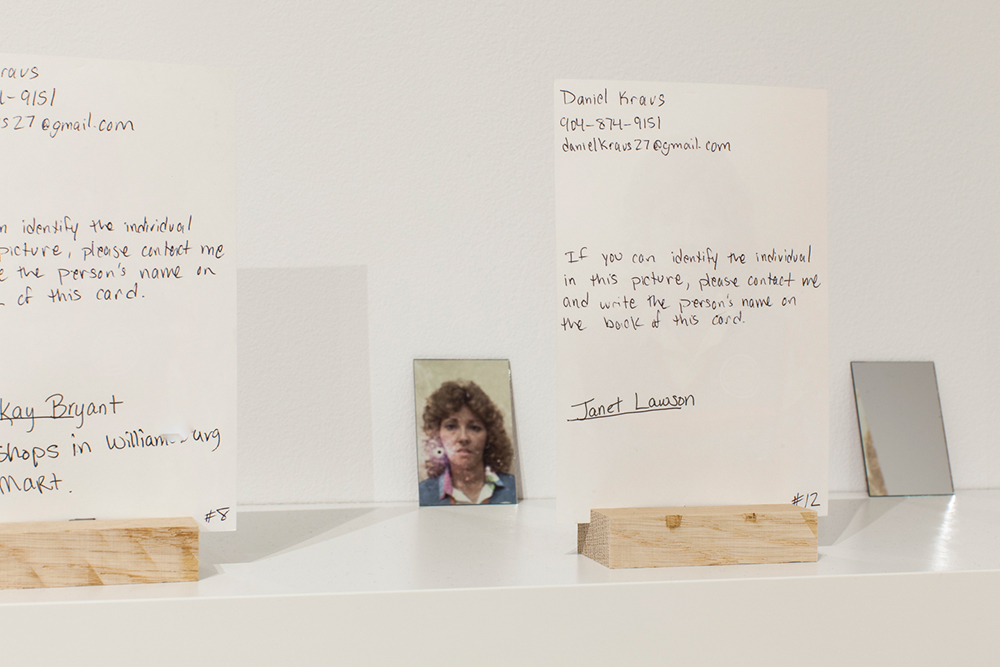

DSK: It proved pretty difficult to find the subjects. I started by trying to contact the Wal-Mart store closest to where I found the negatives. I tried sending emails and calling the store branch for several weeks and then I started to look into renting roadside billboards in the area and using them to post the pictures and my contact information. I never anticipated how hard it would be to contact a specific person at a Wal-Mart branch. I was disconnected or left on hold more than a dozen times. After a final attempt calling the Wal-Mart location I finally connected with a hiring manager who was okay with me sending 4×6’s of the employees. She was kind enough to bring these pictures to a shift meeting and current employees were able to help me connect the faces with names. Once I began to plan the trip to Williamsburg to follow up on information I reached out to the town’s mayor’s office. His secretary, Gina, was so helpful in accessing public records and archives and actually identified several people. This contact was pretty exciting because I was getting to see the fruits of a close knit community. The general response from the subjects was surprise and a pleasant shock. One comment I have in my notes is from Audrey, who said, “I never thought I was this young.” Chet, the oldest of the the subjects was very happy to talk about his experiences and career at Wal-Mart, the friends he made, his family, and his role on the city council. One of the hardest things to communicate was a genuine curiosity and interest I had in their stories and photographs, that I didn’t have a political or social agenda. Of all the subjects I found, interviewed, and photographed, not one of them remembers the photographer. I think there’s something humbling about that.

ML: Tell us about your thought process for the installation. Why did you choose to make the images larger than life? Why was it important for you to include your investigative process in the installation itself?

DSK: The form of the installation was designed to parallel the process of discovery that I experienced in learning about the negatives and the subjects. Including the notes, ephemera, and the original sleeves of negatives was meant to show how the pieces came together, how a person goes from questions to answers and how exciting that process can be. Learning the subjects names and their own thoughts was such a fulfilling part of the project and I wanted that to be accessible for the viewer too. The contact sheet was printed larger than life to exploit the grit and damage of the negatives, the same qualities I was drawn in by initially. The installation showing the new and old portraits together is a rudimentary lenticular giving the viewer some interaction with the work by revealing all the new or old portraits at two different angles. I also wanted the viewer to approach the “pocket” between the old and the new portraits so they could look more closely at the details of the portraits while the old and new pictures surrounded them.

ML: Who or what is inspiring you these days?

DSK: Some of my latest inspirations are books like The Odyssey, Dune, writers like Wendell Berry, and photographers like Sam Contis and Taryn Simon. My long-standing sources of inspiration are my wife, family, faith, and the Florida landscape.

ML: What’s next for you?

DSK: The next big photography project I’m working on investigates the failed and now defunct Florida Barge Canal. The Florida Barge Canal is one of the largest and most expensive failed public works project in United States history. Over 80 years after most of the construction began and at 30% completion, the complex system of canals, dams, locks, reservoirs, and greenways have become landscapes unto themselves. In 1935, progressive politics and New Deal era funding initiated the long awaited trans-Florida canal. Although railway lines ran throughout Florida, a canal would add to the existing infrastructure and modernize the swampy landscape, bringing industry to the burgeoning towns in central Florida. The right of way necessary for the canal route required clearing and flooding thousands of acres and even the displacement of an entire town, called Santos. The townspeople, black share-croppers descended from freed slaves, were coaxed into selling their land to the state for pennies on the dollar. Throughout the canal’s history, both promoters and dissenters used the ideas of, progress, sustainability, and local interests to champion their cause. After only a year of rapid construction, one-third of the canal route was completed. Afterwards came years of protests, underfunding, and congressional acts which brought the canal to an ambiguous slowdown. In 1971, President Richard Nixon cancelled the project, which marked the success of environmentalist who alerted Floridians to the risk of salinization of Florida’s the aquifer, the backbone of the state’s economy. Environmental issues and sustainability efforts are often characterized by two distinctive and opposite arguments; building or not building. However, the infrastructure sites left by the canal project have developed their own eco-systems and environments, and conservationists and environmentalist at odds over which environment deserves to stay. Attempts to demolish the sites and bring pre-canal landscapes back have people facing tough questions; Which landscape is original, more important, and what’s the right thing to do? I’m hoping to spend the summer out in the more isolated areas and waterways of Florida making new pictures for the project.

I’ve also started a channel on YouTube that introduces viewers to photobooks, a medium and subject that’s occupied much of my research and teaching lately. On the channel, The Photobook Review, I introduce the book, the artist, and unpack the themes and issues it discusses. The channel helps to keep me curious, thinking, and share my research with a global audience. I’ve been so encouraged by messages and comments showing appreciation of the videos, because often times the books aren’t available to the viewer for one reason or another. The channel is meant to promote the photobook as an art form.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 3rd Place Student Prize Winner: Mehrdad MirzaieJuly 24th, 2024

-

One Year Later: Nykelle DeVivoJuly 19th, 2024

-

One Year Later: Anna RottyJuly 18th, 2024

-

The Paula Riff Award: Minwoo LeeJuly 17th, 2024

-

Anastasia Sierra and Carrie Usmar: Talking MotherhoodJuly 16th, 2024