Photographers on Photographers: Caleb Cole in Conversation with Jesseca Ferguson

This month we feature our annual Photographers on Photographers interview series. For this effort, we asked the 2021 Top 25 to Watch to share an interview with a hero, mentor, or an artist who has inspired them. Thank you to all who participated. – Aline Smithson

I first met Jesseca Ferguson the way that so many others do, through the vast network of people she has mentored or lent a helping hand. I always say that it seems like Jesseca knows everyone. Not only was she a teacher for over 35 years at The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, but she has made relationships all over the world, from Boston to Poland. We formed a symbiotic friendship over a decade ago: I would assist her with scanning and web work, while she would share her extensive knowledge of alternative processes and other artists I should meet. I always admired how she resists traditional definitions of photography as well as how she prioritizes connection and community. In 2013, she lent me access to her darkroom so I could develop my series Blueboys, and more recently I drew on her expertise in anthotypes to create In Lieu of Flowers. Every time we meet, we have long conversations about both art making and making an artistic life. I want to share one of those conversations with you.

Jesseca Ferguson works at the intersection of 19th century handmade photographic processes, collage, and artist books. Selected public collections holding her work include the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Book Art Museum, Łódż, Poland; Museum of the History of Photography, Kraków, Poland; The Fox Talbot Museum, Lacock Abbey, England, and Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA. Her work has been supported by Art Matters, Inc., the Trust for Mutual Understanding, and MacDowell, among others. Her images and photo-objects have been published in numerous books, catalogs, and articles on the subject of handmade photography here in the US and abroad.

Jesseca lives and works in a co-operative live-work artist building located in the Fort Point area of Boston, MA. She holds undergraduate degrees from Harvard University and Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She received her MFA from Tufts University (in conjunction with the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Currently she teaches at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University (SMFA@Tufts).

Follow Jesseca Ferguson on Instagram: @jessecaferguson

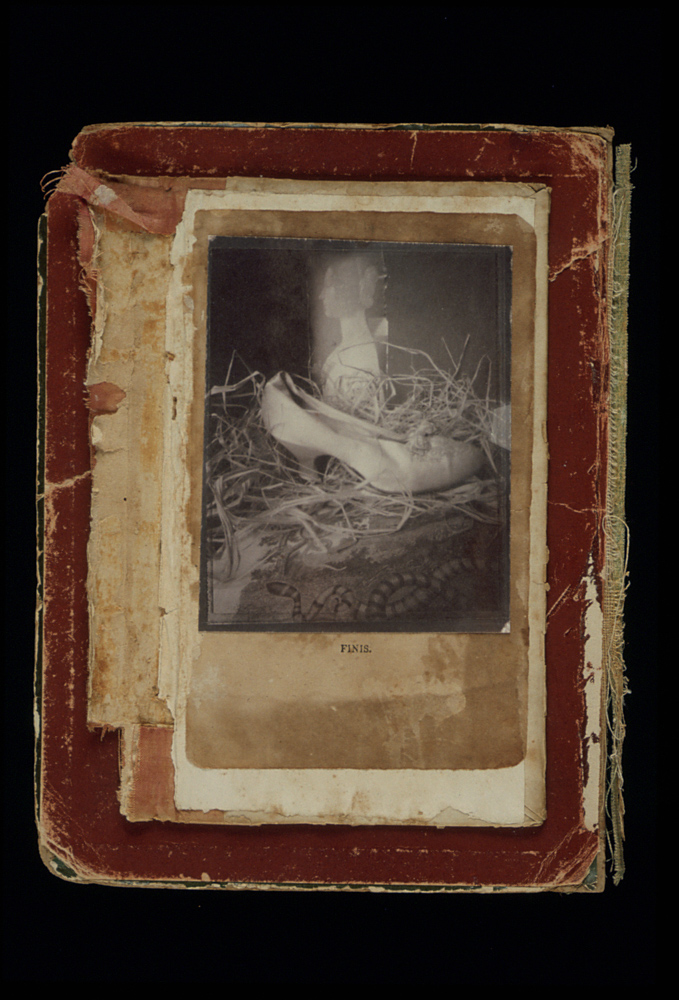

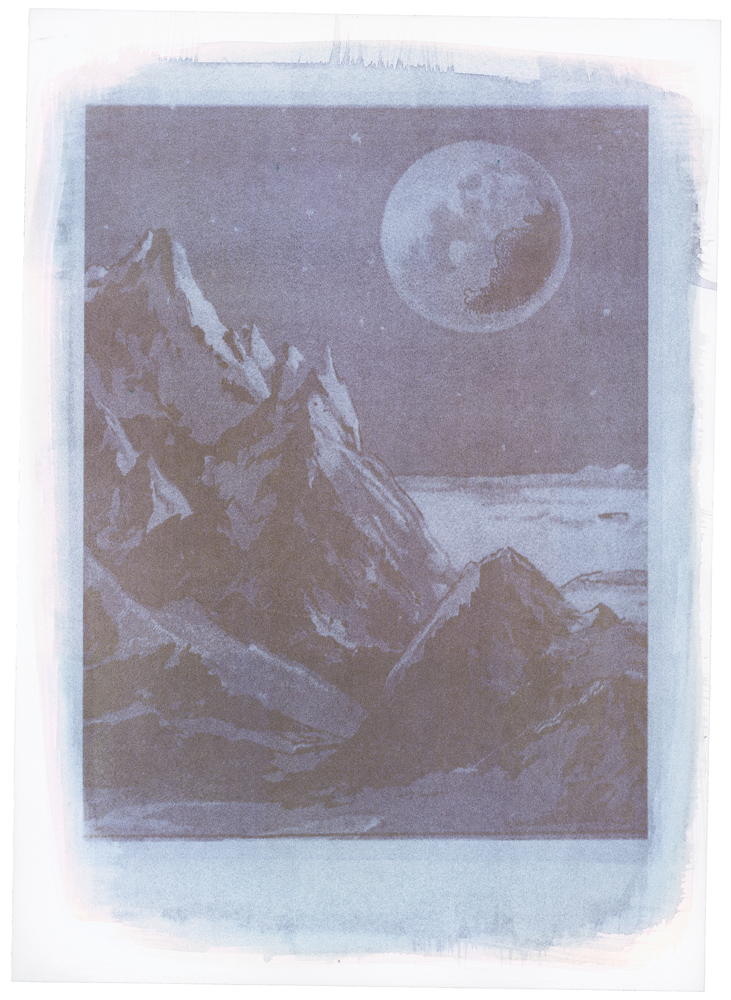

© Jesseca Ferguson, Moonscape diptych (constructed, 2014, cyanotype/gum bichromate, found book boards

Caleb Cole: This series of interviews is called Photographers on Photographers, but I know we both have sort of complicated relationships to the idea of being photographers. I was interested in getting your take on whether you identify as a photographer and if that has changed over time.

Jesseca Ferguson: I’m always puzzled, grateful, honored, flattered, when my work is exhibited in a photography show or collected by a photography department or published in a photography book. Then I say to myself, “They seem to think you’re a photographer, so maybe you are!” I like to think of myself as an artist who uses photography. Photo gives me what I want or need, even if I don’t really know what that is. Somehow photography, whatever that means, is the road for me to follow. And handmade photography specifically is the way for me to go.

I never took a formal photo class, but I would call photographer friends and ask them questions. When I was first starting out, I experienced photography as this kind of technical world, which at the time seemed to be mostly men, where things were either right or wrong. I always felt like I didn’t know the rules and I wasn’t doing things right, so in that sense, I did not consider myself a photographer. I felt a little bit like the person invited to the party where everyone else is dressed up and I’m wearing hand-me-down clothes. I don’t really know what I’m doing, but they did invite me, so…

CC: But then I want to talk to the person at the party who isn’t playing by the rules and is wearing the hand-me-down clothes. And then I want to find out about those clothes. I think that’s what allows you to make the work that you make and have it be exciting and different, because it isn’t sort of like doing steps 1, 2, 3 in the way that everyone expects.

JF: And that’s probably why we’re friends, because we both don’t stay in our lane in the sense that I don’t even what know what the road is. I’m just wandering around somewhere over here. But I remember feeling very intimidated when I was first getting involved with pinhole photo, and I noticed men with big cameras on their chests, with lenses that projected into the space. Meanwhile I was thinking, well, a pinhole camera is a cavity. For me, making a pinhole image is about entering and accepting and going into the dark. A pinhole is an aperture, but not in the way that people think of, like “What’s the aperture of your lens?” Well, I don’t have a lens and I don’t know how big the pinhole aperture is, because I’ve never measured it. I just know that it works. The process is very much about receptivity. Pinhole photo feels very feminine to me in that sense. And these lens-camera-wielding people represented a different way of thinking [about photography] where everything had to be quantified and measured. Looking back, from decades later, and having worked alongside all types of photo colleagues, I appreciate and welcome the vastness of “photography” as we practice it today – with or without lenses, with or without cameras, with or without film, with or without apertures. Now that I’m further along on my own photo journey, I have a much broader understanding of what constitutes a photograph – literally “writing with light.”

CC: That’s also been my issue with a certain approach to photography; that’s just the exact opposite of anything I’m interested in. I really like your description of a different approach that you categorize as feminine—this openness to ambiguity and mystery and not needing to always insert yourself into the scene but to receive these things that come your way and sort of see what happens.

JF: Right! And it’s almost as if the camera is, well, especially with pinhole, is expressing itself. I mean, there’s no view finder, so you just set it up and then you let things happen. You step back and make room for it. I like your use of the word ambiguity. I think that’s a really important principle if we can be open to it and tolerate it, but some people don’t like ambiguity or gray areas.

CC: Is that why we’re both drawn to handmade/Alt Pro photography? I‘m interested in the idea that there isn’t just one way or one recipe or one exact thing to follow. Because I think if I already knew what would happen, I wouldn’t be as interested. But with handmade work I’m always figuring it out. I’ve never figured it out. It keeps shifting and changing and it’s always something to push against and negotiate and figure out as you go. And that there’s always something to be surprised by. I wouldn’t want to feel like I’m a human machine who is just executing some kind of pre-written script.

JF: Well, that is the element of mystery and it’s kind of the enigma of it all. Like, will this work, won’t it work? This approach to photography seems to defy reality. I mean, to make an image from plant materials – to make anthotypes – just seems impossible. It’s a total wonder that it works at all! And the same with pinhole cameras. You can really get into the mysteriousness of it. I like that. When you were talking, I was thinking that this way of working is more about process than product.

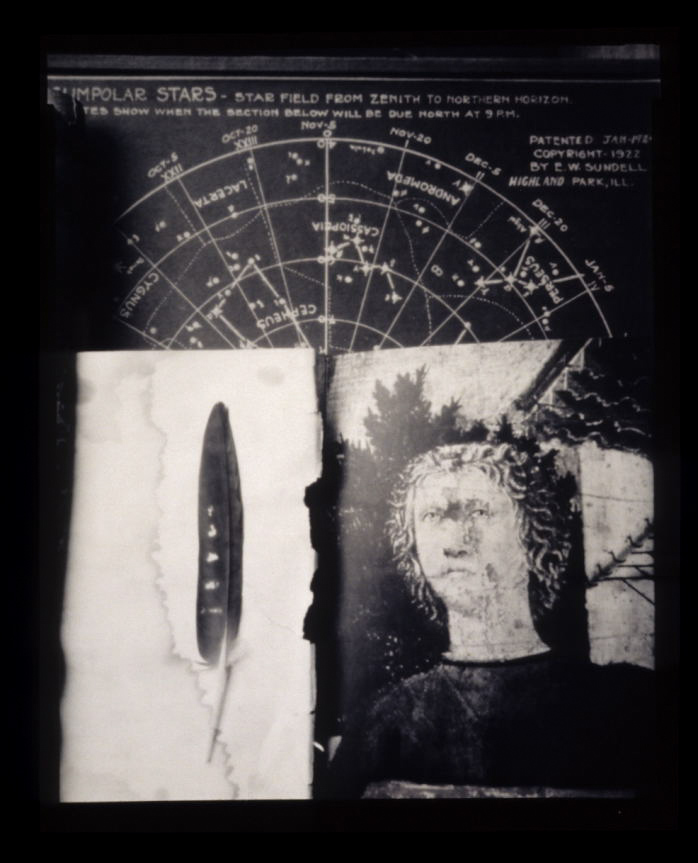

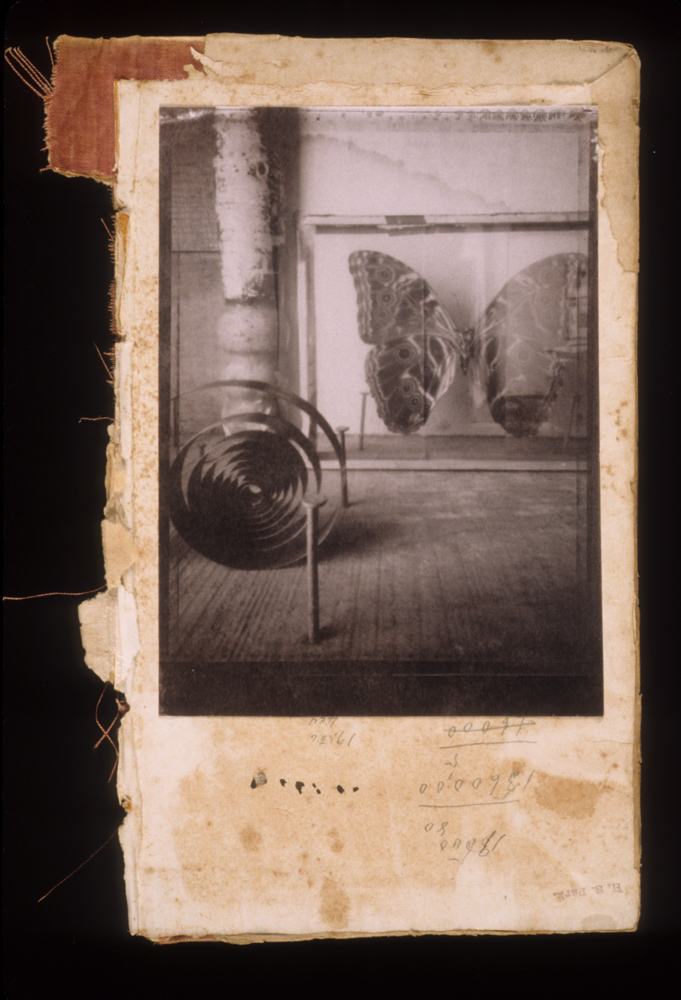

© Jesseca Ferguson, Forms of Flight (constructed), 2001, pinhole salt print (gold-toned), found papers, book board

CC: I definitely feel that way about anthotypes, the mystery and also the process. It’s also about the poetic sensibilities of connecting materials and meaning. What brought you to anthotypes?

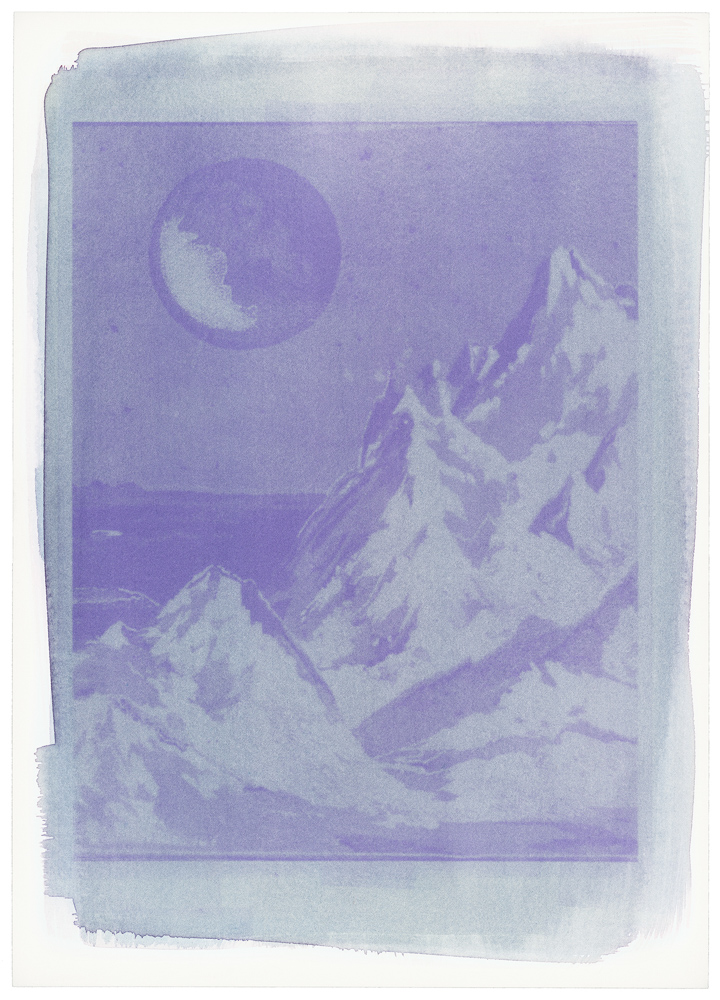

JF: I first saw anthotypes in 2013. My work was included in “Stan Rzeczy: The State of Things,” a handmade photo show in Poznań, Poland, and I went over for the opening. I found a room with a mysterious video [“Anthotype – short story,” 2013] and photograms in impossible colors that I just couldn’t believe— turquoise, pinks, and purples. And I thought, what is this? Is it gum bichromate? That was the only thing I could think of, but when I looked closely, I realized these were not gum prints. The images were semi-transparent and had sunk into the paper, like watercolor. They were not sitting on the surface, like a gum print would. What is this process? That night I met Paweł Kuła, who had made those prints and that video, and he told me about anthotypes. He even gave me some coated papers to try! [When Mary Kocol and I co-curated “Making Pictures from Plants: Contemporary Anthoypes,“ this spring, we included work by Paweł Kula and also by Marek Noniewicz, another experimental Polish photographer.] Well, I kept thinking about those images. And over the years, the large format film I use for pinhole has become harder to get. Plus it really bothered me that I was using developer and all these chemicals. And I had been using found images for a while, so I thought, well, why don’t I try making anthotypes? I crushed some beets and that red anthotype solution was so beautiful. The color was just glowing. It was alive. Using living materials is awe inspiring, you know? Making anthotypes connects you with the natural world. And of course, it’s a green artmaking process, but it’s also like the moon. You can’t hold on to anthotype images. They’re ephemeral and they fade away. Some of the early Sir John Herschel images from 1842 or thereabouts still exist, but they’re very, very faded. My images fade in months or even weeks, even when kept in the dark. I think the anthotype process helps me look at mortality. Well, I don’t know if it helps, but I am more aware of our fragility – It’s one way of approaching it.

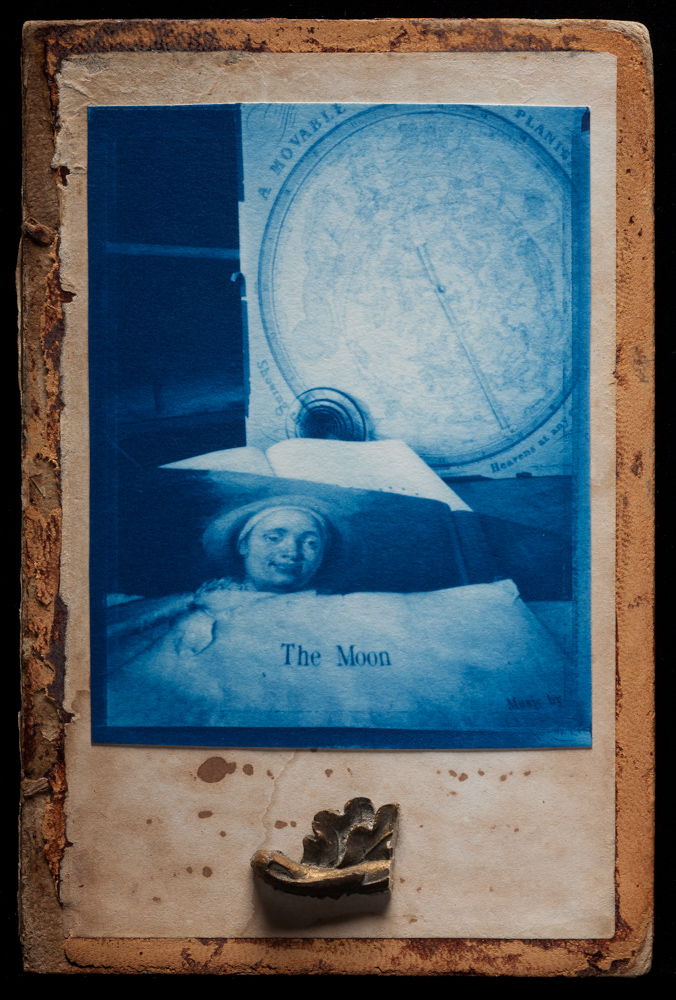

© Jesseca Ferguson, The Moon (constructed), 2010, pinhole cyanotype, found paper, gilded wood fragment, book board

CC: I feel like I experience time differently with anthotypes. When I’m using roses that I grew, I have to use them when they’re ready and coat the paper right away. It’s interesting because I wonder if I developed better solutions, I feel like it would take away this urgency. There’s something about having to do things right away; it becomes a sort of obligation or tending to, and that feels sort of really important to the work. If I found a way to be more flexible or to not have to do it all the time, I don’t know if it would mean the same thing somehow.

JF: I know what you’re saying. It’s definitely about paying attention. And about being present. Handmade photo processes require time, and patience. We gather (and even grow!) the plant materials, then we process them – then do we have enough time to coat the paper? And then the long exposures in the sun — so we just have to let it go and take as much time as we need to make the work. Today, for example, I can’t expose my prints on the roof because it’s going to rain. So I have my contact printing frames propped up in the window. They’ve been there for days. I don’t know how people can say, “This exposure took me seven days.” I have no idea how long my exposures take, because it might be sunny for an hour today, but then next Wednesday it’s sunny all day. I mean, how do you know how long it takes? And does it even matter?

CC: I’m the same way. When people say, “how long do your anthotypes take?” I’m like, it totally depends. It depends how many times I coated the paper, how dense the positive is, the weather, the time of year.

JF: I love that expression “develop by inspection.” It sounds so archaic, like somebody should be in a uniform at an old factory inspecting the widgets. But really, like with so much handmade photo, you must look at your print and decide, well, does this look like enough exposure? Is this print done, or does it need more time in the sun?

CC: It’s all about searching and not knowing exactly what will work until it presents itself to you.

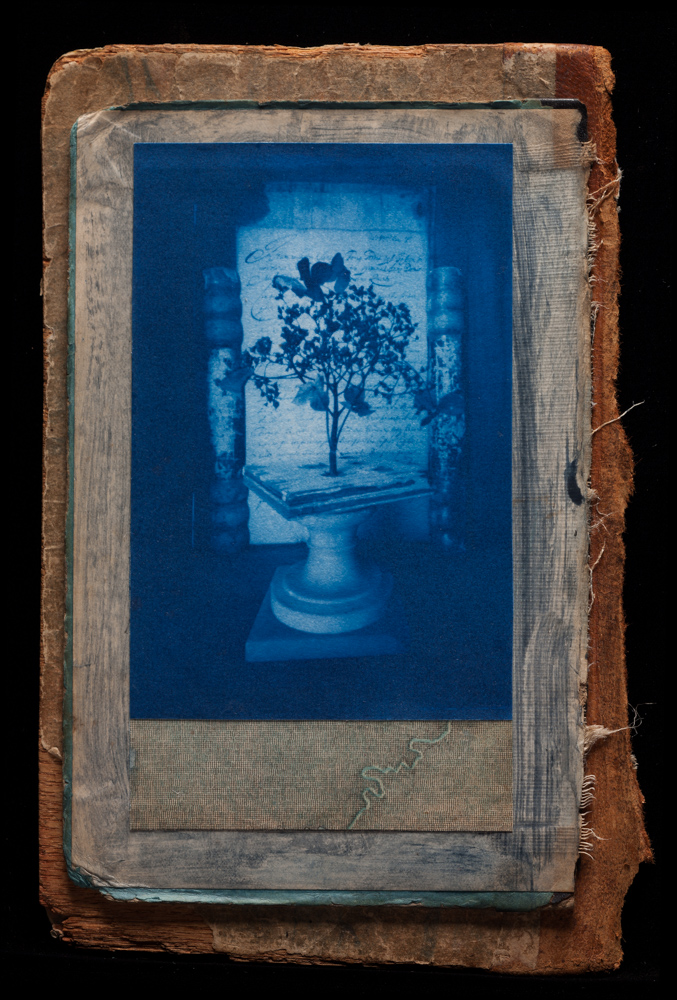

JF: Exactly! You know, years ago, when I was going to a flea market or old bookstore, people would ask me, “What are you looking for?” My answer was always, “Well, I don’t really know, but I’ll know it when I see it.” You have to be open and then you find that object or it finds you, which is really more to the point, I think.

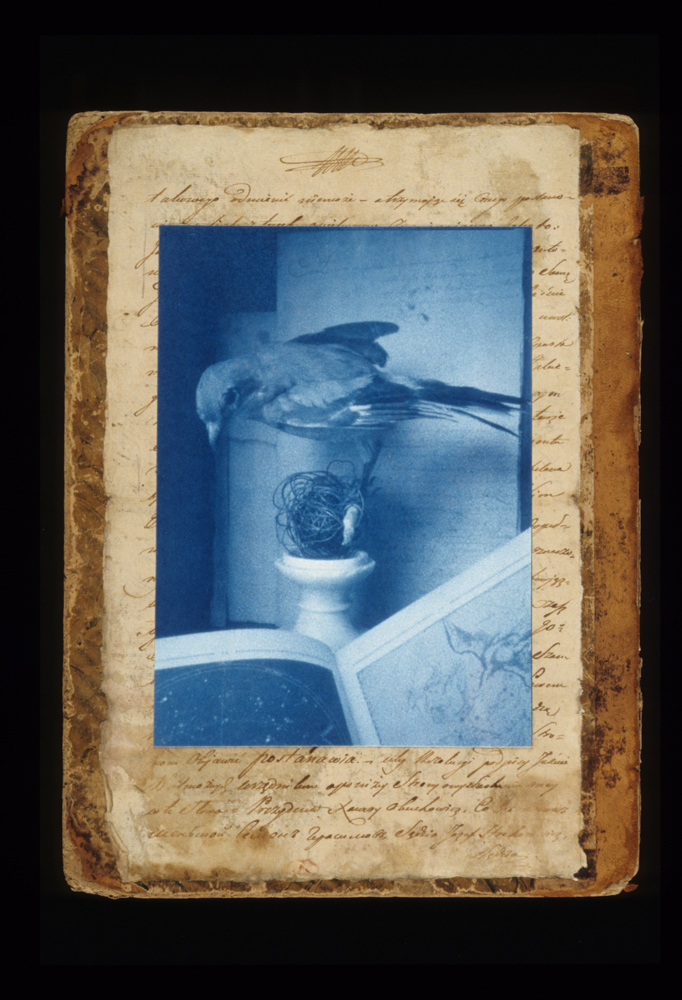

© Jesseca Ferguson, Bird/astronomy book (constructed), 2003, pinhole cyanotype, found paper, book board

CC: That relates to one of the other things I wanted to ask you. I was thinking about the idiosyncratic assortment of objects that you use in your work and wondered if you think of the process of finding them as a process of collecting. How do you come about your materials and how do you think about that process?

JF: The word “collecting,” for me, implies that you must be very organized. You know, this shelf has these things and I’m arranging them and maybe labeling and dating them– it sounds almost scientific. I think of natural history museum collections of butterflies or taxidermied birds. What I do could be more like gathering or accepting. These objects keep me company. We spend time together in the studio. They have their own histories and often remind me of people I once knew. Whether I will use them in my work or not, I don’t really know, but I’m happy that they’re here. I don’t feel that I’m aggressively going out and saying, “Well, I have three wooden horses and I need at least six more.” I mean, I might, if I had a specific project in mind, but that’s not the way I orient myself. I think I’m more open to receiving things.

© Jesseca Ferguson, Winter Garden (constructed), 2010, pinhole cyanotype, found papers, book boards, ink

CC: Someone once said I was a custodian of the things I collect, and I like thinking about the responsibility and relationship I have to them outside the, well, not to make everything gendered, but the traditionally male view of collections as about ownership, conquest, of purchasing to possess, as opposed to a dynamic that maybe that isn’t about the taxonomy or the organization, but something that’s way looser and something that’s maybe not so hierarchical. You know, the way you’re talking about objects, I’m thinking about these other approaches that make you resistant to use the word collecting and instead gravitate to gathering or receiving.

JF: I think the word custodian is a really interesting one. I also thought of the words guardian or protector. It feels almost familial.

I have this hundred-year-old pair of wedding shoes that I bought a long time ago in an antique shop. I was in art school, and waitressing, and I didn’t have any money. I would walk by that antique shop and these shoes kind of haunted me. They’re really beautiful. Finally I just thought, “What the hell? I’m just going to buy them,” even though they cost maybe 25 or 50 dollars, which in the late seventies was a lot of money. For me, at least. But I was really happy to have them. I drew them for a while, and I’ve photographed them with pinhole. I haven’t done anything with them for years, but I feel like I’m responsible for them. They’re here; they’re in this glass cabinet; they’re safe. And I believe that you need to have a certain patience and a certain faith when these objects come to you.

I would say that my father was a bit of a hoarder, and so there was always this anxiety: “Uh oh, I might be becoming Pop!” I don’t know what his objects meant to him. I think there was a sort of poetic resonance for him about certain objects or letters that he kept. In fact, I have a lot of these objects because I settled his estate and had to pack up all that stuff. And I’m finding it hard to get rid of his things. But there are certain objects that are kind of like a tuning fork; there’s something there that you need to pay attention to, something that’s important. These things are useful, but not like nuts and bolts I’m going to use to fix my door when it breaks. These are poetic objects that mean something. At some point, I’ll know, or I’ll be guided, and they’ll play a role in work that I’m going to make. Just like some of the moon images that I’ve been using. Those are from a little pocket moon atlas, I think from the early part of the 20th century, that I found in an old bookstore in Kraków. I remember thinking at the time, “Well, what am I doing with this?” I bought a couple of books at this place, and I’ve used them over the years, sometimes obsessively and sometimes not. And really, those books had nothing to do with anything when I bought them, but there was an attraction, and I felt the glimmer of possibility.

© Jesseca Ferguson, Lunar Landscape 4, 2022 digital print from 2021 anthotype (turmeric, purple stock)

CC: I also think the refusal to believe that everything must be useful is a kind of resistance to capitalism. Does everything need to be useful, or can it be, I don’t know, something else? I guess it’s hard to break out of that idea of utility, because if it makes you think or if it makes you feel, or if it brings you back to the moment, all these things are useful. But I think the pressure to be useful is something that I’m always trying to push against.

JF: Do you think it has to do with consumption? Like it’s useful, it’s a box of pasta. We’re going to eat it for dinner.

CC: Yes. And then you’ll need to buy more!

JF: Exactly. It’s consumable. Whereas these things [I use in my work], some of them are definitely over a hundred years old and some of them I’ve had for 20, 30, even 40 years. I mean, like those wedding shoes. If I bought them when I was a student at MassArt, then that’s 42 years ago. That’s pretty shocking. And even though I haven’t “used” them for a while, they’re there and I enjoy them and I’m thinking about them now and we’re talking about them.

CC: You mentioned your pocket moon atlas. I have a strange connection and fascination with the moon. And, and I have my own reasons, but I’m very curious what it is about the moon for you that’s made it a running theme in your work.

JF: Sometimes I wonder about it myself. I have made moon images on and off for a long time. Somebody gave me an atlas of the sky, and some old star maps, that I have used over the years. I don’t know why he gave them to me. He just found them and thought I would like them. I was born in July, the sign of Cancer, supposedly ruled by the moon. And I always thought, oh, silly. But actually, the moon has been a recurring theme and interest since childhood.

I remember one time I was about 8 and I was walking on the beach at night with my aunt and there was a full moon. The moon’s reflection made a glowing pathway on the water, and I was just convinced that I could walk on it. It looked so real. And so, I just kept trying to catch up to it. And I don’t know what it is, the nature of reflection or something, but I could never be even with it. I could never reach it. So here was this glowing orb that was unattainable and beautiful. It came and it went. I couldn’t hold onto it. And it’s kind of like the way of working that we’re talking about. It’s elusive; it’s alluring; it’s engaging. We can’t grasp it and we have to wait for it to come back.

CC: That’s perfect. I love that.

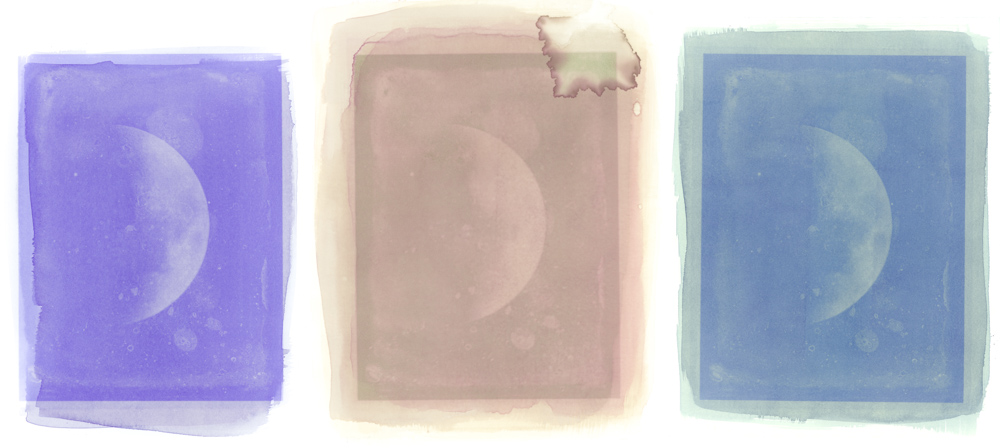

© Jesseca Ferguson, Anthotypes of the moon, 2022, Plant materials/titles L to R for 3 moon images: Purple moon – homegrown geraniums, What happens when it rains – Swiss chard, carnations, pokeberry, Blue moon – homegrown pansies

CC: Last question. I know you just retired from teaching, and I wondered if you have any advice for young artists about creating a satisfying— I don’t want to say successful—so, a satisfying life as an artist?

JF: That’s a great question. The word “successful,” my husband Mark always says that if you keep doing your work, that’s success. Even if you’re not on top. For example – many people I went to art school with may still be in the arts. They might have become a curator or a designer or something else art-related, but they may not be a “fine artist” working in the studio anymore. It’s very hard to keep doing that. And if you’re still making your own work and being true to yourself in that way, in my mind, then that is success. And I would say to anyone starting out to believe in yourself and have the courage of your convictions. And even if someone pooh poohs your idea and says, “Well, that’s weird,” or “Somebody already did that,” just try it anyway. Just go for it. You’ll find your way. I think it’s also important to have community, to have other fellow travelers. Then you can encourage each other and talk things out with each other. That’s really important, too.

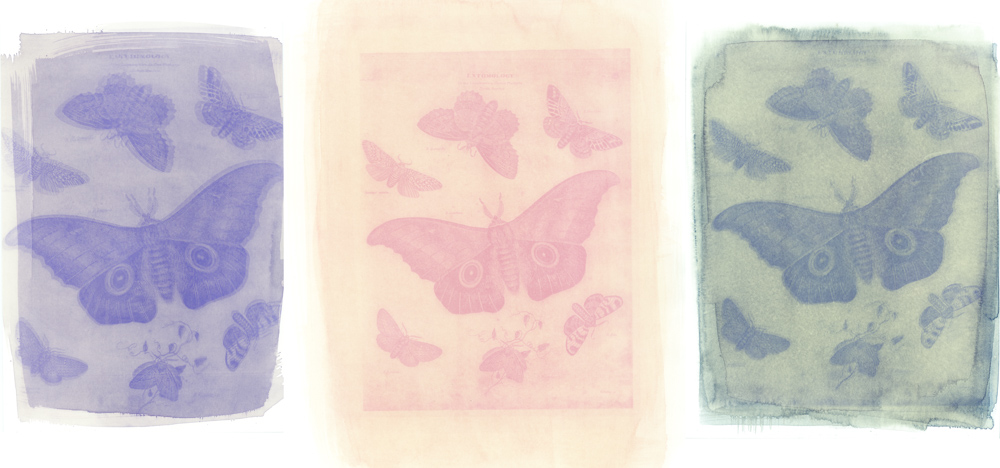

© Jesseca Ferguson, Entymology: Moth anthotypes, 2022, Plant materials/titles L to R for 3 moth images: Purple moths – homegrown geraniums, Pink moths: homegrown amaranth, Blurred moths: homegrown pansies and amaranth

CC: You’ve always been so great at creating community, so willing to help other artists or to connect artists with one another. That’s how we met. I feel like you know everyone, but that’s a testament to the kind of person you are.

JF: Thank you, Caleb! I’m very touched by that. I mean, in a funny way, I’ve often felt lonely. I think it can be lonely to be an artist. I’m glad to be married to a composer who understands. And so, if I find someone who’s doing similar work, I feel this kind of kinship. And some of what I’m most happy to have done has been to curate shows of work by other artists or to make things happen for people to connect. And I think that all ties in with teaching. I always liked to envision a semester or a course as a kind of a journey: we’re all in this little boat together for this time. So let’s connect and make it meaningful. So I think that’s been in the back of my mind– I’m looking for connection. Well, in my studio I try to connect objects, so maybe with people, same thing. It makes me happy when people connect.

© Caleb Cole, Blue Boys, 2014, Collected glass negatives, printed as cyanotype on classified pages from 1970s Drummer Magazines

Caleb Cole is a Midwest-born, Boston-based artist whose work addresses the opportunities and difficulties of queer belonging, as well as aims to be a link in the creation of that tradition, no matter how fragile or ephemeral or impossible its connections. They were an inaugural resident at Surf Point Residency and have received an Artadia Finalist Award, Hearst 8×10 Biennial Award, 3 Magenta Flash Forward Foundation Fellowships, and 2 Photolucida Critical Mass Finalist awards, among other distinctions. Caleb exhibits regularly at a variety of national venues and has held solo shows in Boston, New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, among others. Their work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Newport Art Museum, the Davis Art Museum, Brown University Art Museum, and Leslie Lohman Museum of Art. Caleb teaches at Boston College and Clark University and is represented by Gallery Kayafas, Boston.

Follow Caleb Cole on Instagram: @calebxcole

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026

-

Carolina Baldomá: An Elemental PracticeJanuary 5th, 2026