Photographers on Photographers: Tayla Nebesky in Conversation with Terri Weifenbach

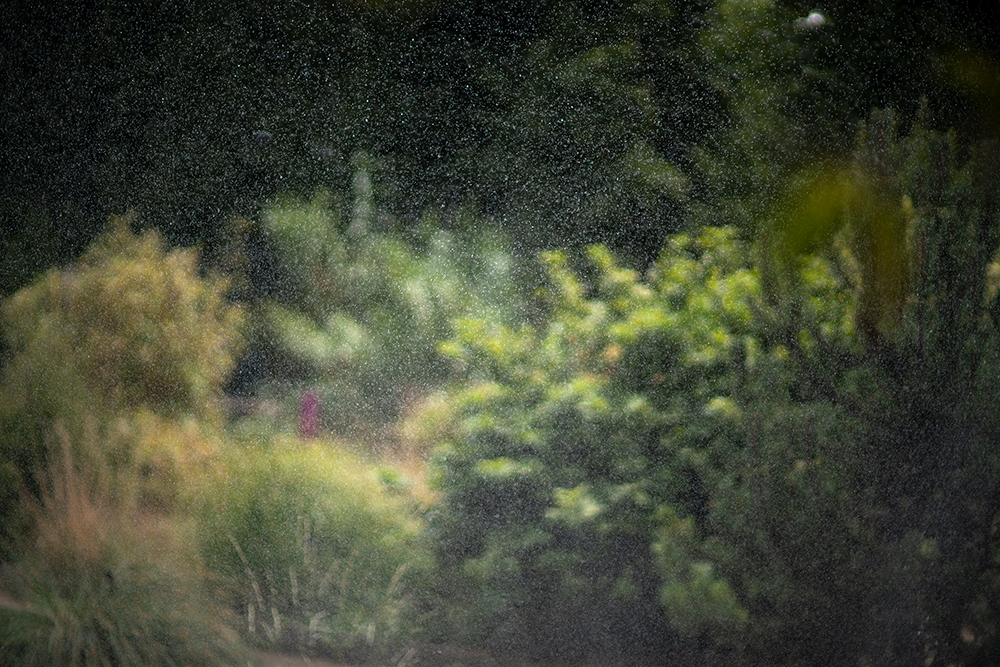

Terri Weifenbach’s photographs offer a passageway into the natural world that is all around us. Photographing scenes that are often unappreciated or overlooked, Terri’s curiosity and patience is almost tangible within her pictures. Her distinct use of color and focus combined with the use of a wide aperture make her photographs instantly recognizable. I love Terri’s work for her recognition of nuance and ability to translate small, everyday moments into images that feel familiar yet surprising, simple yet strikingly beautiful.

Bookmaking is central to Terri Weifenbach’s artistic practice. Since her first book, In Your Dreams, was published in 1997 she has authored twenty more titles including Cloud Physics, Lana, Politics of Flowers and Gift (co-author Rinko Kawauchi). Publishers include Atelier EXB, The Ice Plant, Nazraeli Press and Loosestrife Press. Weifenbach’s Instruction Manual concept realized and initiated Nazraeli press’s One Picture Book series with #01, #03 and #04. In Your Dreams was included in The Photobook: A History Volume II by Martin Parr and Gerry Badger.

She has had numerous solo and group exhibitions in the United States, Europe and Japan and published widely in periodicals such as Audubon, Union Magazine and IMA Magazine. Terri’s first solo museum show took place in 2017 at Izu Photo Museum in Clematis no Oka, Japan. Her work can be found in international collections such as the Center for Creative Photography in Arizona, Sprengel Museum Hannover in Germany and the Musee des Impressionismes in Giverny, France.

Weifenbach is also renowned as a teacher. In addition to national and international workshops, she has taught at the Corcoran College of Art and Design, Georgetown University and as Lecturer at American University.

Born in NYC, raised in Washington, DC and educated at the University of Maryland, Terri Weifenbach spent a dozen years from her twenties living in New Mexico and California. She now resides in Paris, France. She is a Guggenheim Fellow having received the distinction in 2015.

Follow Terri Weifenbach on Instagram: @terriweifenbach

Tayla Nebesky: Do you approach a new project with a specific idea in mind, or does it manifest itself later in the process? How do you know when a body of work is finished?

Terri Weifenbach: It seems to me to be a sort of stroll where it’s all connected — the work previously done and the work to come are inseparable. In a way I’ve had the same thoughts as in my beginnings, exploring and investigating around this form, if you will, with different aspects and entry points. It’s one story, it belongs together despite the defining covers of a book. To exemplify this, my second book, Hunter Green, continues the roman numeral numbering started in the first book, In Your Dreams. So, asking when it’s finished — it isn’t ever really. But I concede here, because books do have covers and decisions have to be made. I know the work is ready to be “contained” when I don’t feel like I’m stretching to reach the description, when I no longer feel the need to search immediately for more. When asked this question, I give thought to how a poet knows a poem is finished, or a painter, a series of paintings.

© Terri Weifenbach, St. Catherines Island Georgia, USA, Partly Cloudy, 29.5C, 93% humidity, April 23, 2016

TN: Your first photobook was published in 1997 and since then you have released 20 more. What draws you to the photobook format?

TW: I sort of fell into it, then it started to form the way to go forward for me. I was studying photography in the late 70s, some books had been around for awhile, such as Robert Frank’s, The Americans, Walker Evans’ American Photographs and William Klein’s New York. But also new, in my face was, William Eggleston’s Guide. All these are more than collections of images or catalogs — sequence rules in non-narrative ways. It felt new then and the possibilities endless, and I fell for the thought process, the sequencing and the whole that came from the parts. And there is a bit of building — it’s exciting all the way to the head and tail bands.

TN: You’ve made photographs in a variety of settings – from as locally as your backyard to California, Washington DC, Paris, Japan. Does location have an effect on your approach to making pictures?

TW: Location affects the physical approach I have, meaning, where my perspective might be (low, high), if there is space or it’s closed in, if I have time. The largest hurdle for me is dispensing with the obvious when in a new landscape. New places are new experiences and I treasure the possibility to be in new landscapes beyond measure (especially now, post confinement). No place is ever the same day to day, and when the place is a new one to me, I don’t see the daily nuance as easily. It takes time. So places that are familiar have an intimacy for me and new places, a more palpable excitement. Whether this can be seen in my images is not for me to say.

TN: In the past you have mentioned paintings to be an influence on your work. Who are some painters who have influenced you, and why?

TW: Hmmm… so much easier to tell who than why and I’m not sure how they influence my work either, but I look at paintings much more often than I do photographs. Some painters that interest me are; the Barbizon School painters, Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet; then Edouard Vuillard and Odilon Redon, Pierre Bonnard; more contemporary, Cecily Brown, Laura Owens, Julie Mehretu and there are many more. I think about how and where painting is different than photography and the influence they have on one another. The difference of systems of choices, of color.

TN: You worked as a darkroom printer for over two decades. How has your experience in the darkroom impacted your work, and particularly your use of color?

TW: It was indispensable to have complete control over the process back when it was analog. I worked with different papers and types of film, Kodak, Agfa, Fuji for clients. Working with photographers to produce what they wanted and with their choices taught me the abilities and limits of the materials and helped define for me my choice of materials. For analog this was great as I was essentially experimenting with all of it. Of interest is that I printed color for close to ten years before shooting it. The color film Ektar 25 came out in 1992 and it changed everything for me with its bright palate and tight T-grain technology.

TN: Have you always felt connected to nature? Has photography enhanced this connection?

TW: I have, yes. My parents, particularly my father, showed my sister, brother and me details, taught us how to wait and watch, he explained cycles, and most importantly, showed us how to handle the dangerous parts of nature without being frightened. I was three when he showed me where the hiding places were for snakes (there were two varieties of poisonous snakes where we were), when crossing a log, to stand on it and look before placing a foot on the other side. I’ve always felt comfort, even when vigilance is needed, and it has surprised me and saddened me that others do not. Photography has kept me connected to nature by giving me the right to go to the magical places I never could have seen otherwise. Possibly the lesson of waiting and watching also taught me how to photograph. I have to answer, yes, as I don’t know if I would’ve been so directed without the camera in my hand giving me a reason in those moments I needed one.

Tayla Nebesky is an American photographer based in the UK. Shortlisted for the Sony World Photography Awards in 2021, her work has been published both in print and online by organisations such as The New York Times, The British Journal of Photography, Aesthetica Magazine, and Der Grief. Having recently completed a Masters in photography at UWE Bristol, she makes photos in a lyrical and observational manner.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025