Argus Paul Estabrook: Half Eye, Half I

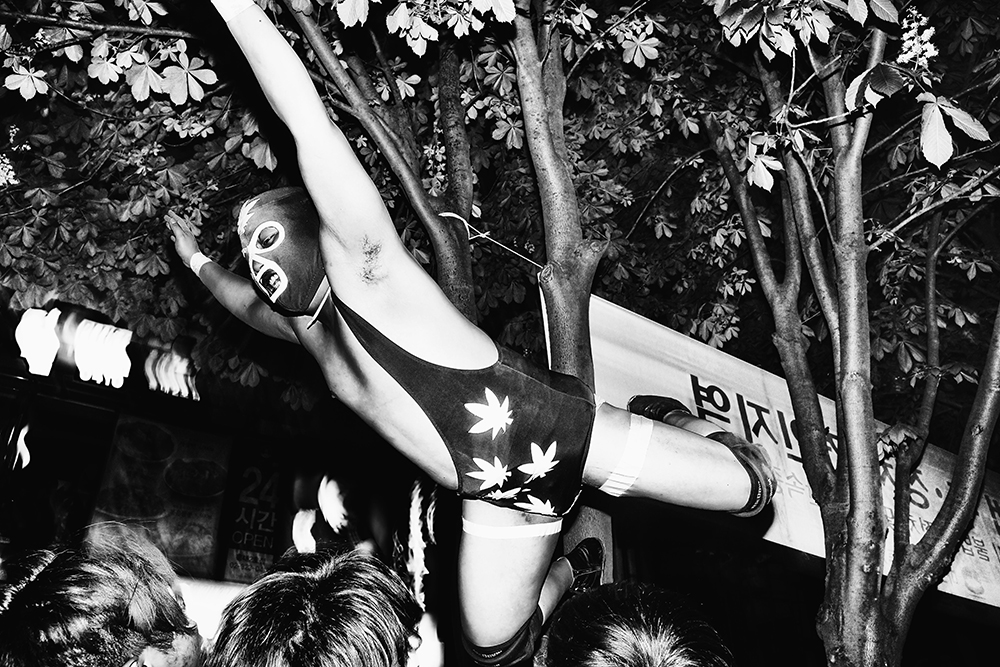

I met Argus Paul Estabrook through a mutual friend in my last year of undergrad at Virginia Intermont College back in 1997 or 1998. We didn’t reconnect until the invention of social media when I became much more aware of his work. Back in 2021, I attended the opening of his exhibition at Emory & Henry College where he also spoke about the work. I walked away thinking I finally really knew him. Many of the conceptual street photographs are expressive with the use of motion and camera movement that forge a rhythm that captures the energy and chaos of a crowd, police blockade, riding the subway, or walking down the street. Many of the encounters seem brief, creating a pace to the images that feels rapid. The photographer’s vision combines light trails and the starkness of the flash as an element capturing the awareness of time even in the most minor movement. When not employing motion, his use of other techniques often creates a sense of surreality and duality. There is usually a contrast between what is real and what is a reflection or mirage. Argus Paul’s stylistic imagery is used to communicate his visual observations of life in Korea and places beyond.

I’m a Korean American, lens-based artist working in South Korea and the USA. I use candid moments and chance encounters to share a personal journey that often explores the intersections of identity, race, and politics. Artistically, I consider myself a street photographer that sometimes takes the camera inside to tell private stories. -Argus Paul Estabrook

Argus Paul Estabrook is a conceptual street and documentary photographer. A biracial Korean American, he grew up in the USA and began making photographs of South Korean life after receiving his MFA in Studio Arts at James Madison University. His work has been awarded by the Magnum Photography Awards, Sony World Photography Awards, LensCulture, Life Framer, IPA, as well as exhibited at the Miami Street Photography Festival and the Aperture Summer Open: On Freedom. Also, he has been selected twice as a Critical Mass Top 50 artist by Photolucida and is a three-time recipient of PDN’s Annual Exposure Award. In 2022, the Paris International Street Photography Awards (PISPA) named him Street Photographer of the Year.

GB: Tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you became a photographer?

My childhood was a bit lonely and full of isolation. I was born in South Korea but my family bounced around the globe due to my father’s engineering career. After he left his company, I ended up in a predominately white farming community where I grew up on an organic orchard. There weren’t really any neighbors so I had to find ways to occupy my time without going stir- crazy. So I dabbled in everything when I was a kid, drawing, playing music, writing comics, etc. That said, it wasn’t just the remoteness of living in the country that was isolating, but also the racism that I endured that made me feel alone. So for me, art was a way to run away without leaving home. As fate would have it, while I was in high school, the art teacher wouldn’t let me into the advanced classes. The only other creative class available to me was photography. My dad gave me his old OM-1 camera with a 24mm Zukio and a flash unit. Immediately, I was completely hooked. I remember thinking this is the closest thing to magic that I’ll have in my life.

GB: When did you decide that documentary and street photography is your path and what attracted you to this direction?

I don’t know if I ever decided on a path. More like, my personality just leaned in that direction so I kept walking down that road. Growing up, I think the racism I encountered pushed me to use the camera as a way to speak up or find a voice. I’ve always seen it as a vehicle to explain how I feel about something. And street photography has always been there for me. Even now in the photography industry – where people try to promote diversity – there’s still too much gate- keeping but the streets are always open for the rest of us. A few years back, I felt I had enough of trying to “make it” and just decided to focus on street work because it was the one place that felt familiar. The street is a metaphor for life. I like the unknown. I need to know there are a million ways to travel down the same path. Like many street photographers, “The Americans” really resonated with me. Not just because of Frank’s images but also the words of Kerouac. Also, I greatly admired writers like Hunter S. Thompson and Bukowski. I suppose my photography evolved the way it did because I wanted to be a storyteller and a poet, too. To me, street photography is simply candid image-making in public spaces or private spaces if you’ve got permission. It’s how I make sense of the world. When I practice photography, I feel I’m practicing a kind of alignment of my soul where I suddenly have a spontaneous understanding of the moment- it’s like being part of an eclipse, not just spatially with where you stand and perceive a photographic opportunity but also syncing your “emotional” self with the moment. It’s like lining up a personal internal-ness with our shared external reality. Some people talk about the decisive moment as if it were like safari hunting. I hate that. For me, the decisive moment is more about finding a kind of harmony. Or if we must speak about it in terms of sport, I’m a fisherman with a small net.

GB: Talk about the use of motion and movement through slower exposures in the images. It is something that you employ consistently and I have always loved.

When I use long shutter speeds and flash, it’s often to represent time or the energy in an unfolding scene. Sometimes, I’m trying to portray sound. Motion and movement help convey a sort of psychological state of mind that I want to express. I guess I yearn for the feel of something continuous. Life has definitive moments but they’re not always bookended neatly, at least not for me. Not to say I’m rebelling against the idea of the definitive moment, because being in the moment is of the utmost importance, but I am interested in how one decides something is “definitive” or not and how personal subjectivity plays into that. When I’m shooting, I feel I’m either photographing for a momentary facet of life that only exists for a 1/125 second or trying to portray something that feels sustained. Everything feels transitory to me anyway. Using the drag shutter technique or slow exposures, as well as taking advantage of things like mixed lighting, has allowed me to make the camera take the pictures I want, rather than letting the camera take the pictures “it” wants. And what I want to make are photographs that are felt first and then seen. It’s really about portraying an internal perception. It’s a strategy on how I can get someone to be in my head rather than in my shoes.

GB: How do you think having the perspective of being both Korean and American affect your work?

Being biracial, I think it colors everything. It’s bitter-sweet because I feel I will always be an insider/outsider in both countries. It’s like I’ll always have a place in both worlds but not fully. So the concept of identity and home is always at the forefront of my thoughts. You know, I’ve had people tell me I’m not an authentic Korean or a real American, which is difficult to emotionally navigate. Ultimately, as a creative, I feel I’m able to repurpose negative energy into something useful or at least I try to. During my MFA, I was lucky enough to meet the Chinese artist Xu Bing and he told me some advice that I’ve taken forever with me. And that advice was to see the limitations facing you and by acknowledging them, one can find opportunities to grow artistically. I took that to mean trying to find strengths in my limitations or limitations placed on me. So, being a mixed-race photographer, I began embracing my identity as an artistic “half-eye” or someone born into duality. Philosophically, I sense my camera takes that feeling a step further in practice because it proves to be an active interface between my outward observations and inward thoughts. I find thinking this way allows me to transform the viewfinder into a window of reality that is both open and reflective.

GB: Talk about how you decide on a visual narrative? Do you shoot first or do you decide before you make the photographs?

That’s like a chicken before the egg type question, haha. I guess it happens two ways. One, I’ll have an idea and want to try it out to see where “something” leads. The other way is I’ll notice a trend in my images while free shooting and then this generates the idea to want to try that “something.” So it’s a bit circular. I think I work a bit holistically – going with the flow, trying to find meaning in the world around me – that kind of thing. I’ve always seen my work as a poetic education that I’m sharing with myself. One reason I primarily shoot in Korea is to gain cultural insights. It’s an act of learning and I try to keep the perspective of a student. I don’t want to know something so much that there isn’t anything left. Mastery is an illusion anyway, a beautiful distraction that interrupts the flow of actually being present. When I share a narrative, I hope to extend that feeling of flow and curiosity to others. I want people to feel wonder. I want people to feel immersed and think a little bit about what’s going on.

GB: Why it is important to have a conceptual element to your documentary and street photography?

For how I use the medium, I think that photography is the art of taking something out of context and then recontextualizing it to share a meaning that you’ve imbued into an image or series of images. To me, it’s necessary to have a conceptual element in my documentary and street photography because everything I am shooting is through my eyes, through my heart. The lens and camera just happen to be in front of my thoughts. And my thoughts are exactly what I’m trying to share, finding facets of them throughout this communal landscape we all share. We live in an era where everything is mediated by images and we for the most part consume images passively. The only act of consideration for the viewer is to see and accept the caption or if the ad matches the image. If artists don’t control the context of their work, then what is the point? For me, conceptualizing isn’t just about explaining personal thoughts, it’s about vision and what some might call authorship. Personally, when I tell a photographic story, I’ve listened to the seed of the idea first because it informs me what it needs to grow. And then it’s a compromise on how much I can actually do for it. The seed is the concept and growing it is the recontextualization.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025