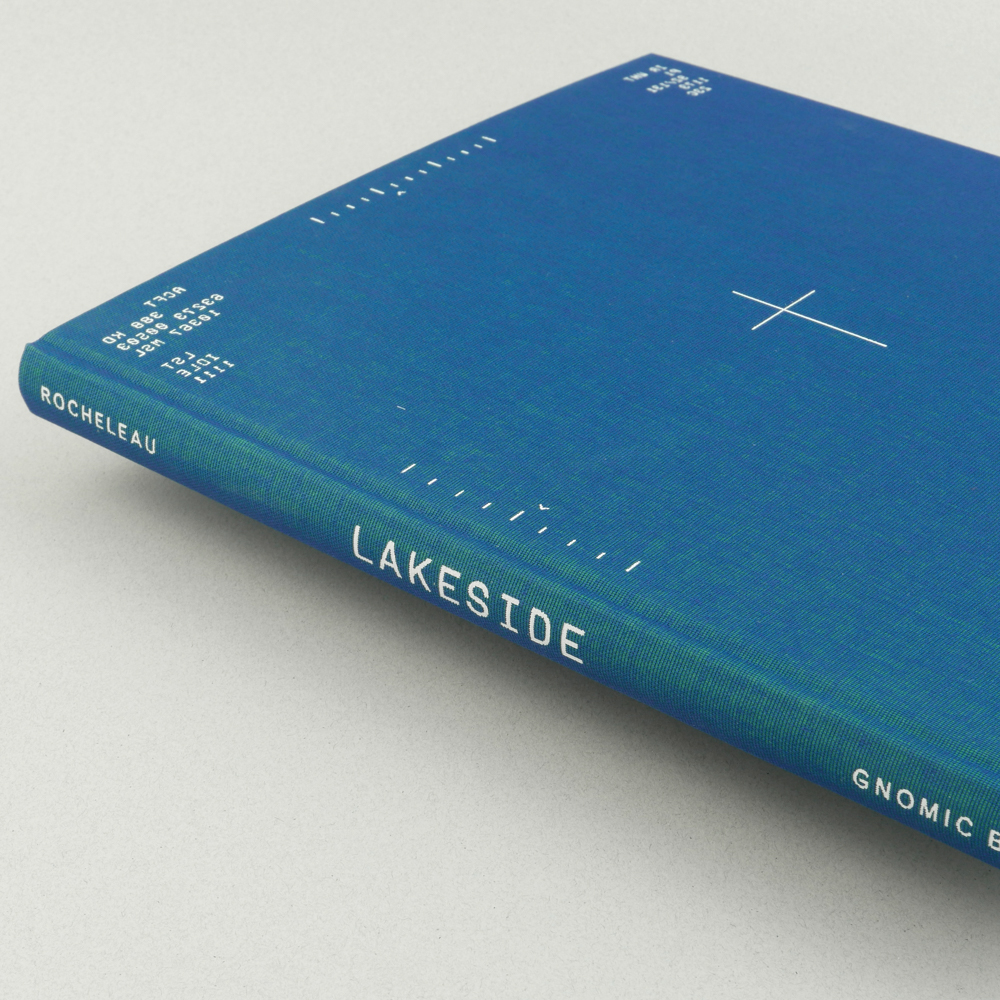

Shane Rocheleau: Lakeside

Lakeside is a neighborhood in Central Virginia where urban sprawl and modern culture threaten to encroach upon a traditionally conservative, blue collar way-of-life. Lakeside is also the title of Shane Rocheleau’s latest monograph, his 3rd with publisher Gnomic Book. Rocheleau began this work weeks after the 2016 presidential election and completed photographing just weeks before the insurrection at the US Capitol. Faced with the darkness of the American predicament, Rocheleau makes an attempt to bridge the divide by looking, as if bearing witness can help close this loop of human connection. Through a series of photographs of this town and its inhabitants, chaptered with consequential design, we are taken on a symbolic journey through the cyclical and sometimes dark nature of all living things.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Tracy L. Chandler and Shane Rocheleau.

TLC: Your book derives its title from a real place, Lakeside, VA. Lakeside is a very generic name for a town. For me, it reads like “Anytown, USA” and points to that play of specificity as a stand-in for universality. Do you live in Lakeside? What is your relationship to this place?

SR: I do live in Lakeside. It’s a little neighborhood along the northern border of Richmond. My wife and I decided that we wanted to own our own place, but we didn’t want to be house poor, so we qualified for a smaller loan using only one salary. Lakeside arose out of the post-WWII boom. It’s a historically white, blue collar neighborhood because of red-lining and the racist implementation of the G.I. Bill. It hasn’t been overtaken by the city sprawl just yet. Which is to say, it’s only at the beginning of its gentrification, and, to some degree, my wife and I represent this. But while many of us conceive of gentrification as only a racially defined displacement, Lakeside’s is almost entirely wealthier white people displacing

poorer whites.

When I first entered the neighborhood, looking for a home, it was clear how peculiar it was, at least to me. Ninety percent of the yards have fences on them, and ninety percent of those fences have unambiguous signs tacked up. The Keep Outs and No Trespassings almost narrate my walks here. In a strange way, it’s the most exclusive place I’ve ever lived. It’s as if it has a gated community disposition, even though the gates are in different places and it’s way uglier. Or maybe not uglier? Maybe it’s actually way more beautiful, teeming and more human. It’s beautiful in a way that McMansions and their prim and proper lawns just can’t be. Maybe in this way Lakeside feels more like my brain?

TLC: Yes, with gated communities as well as with Lakeside the fences are setting boundaries and sending messages like “This is mine.” And “Others keep out.” Literal signs of possession and division. Anything that crosses that line is a threat. It breeds resentment, fear, and isolation.

SR: That isolation is palpable. So is the feeling that there are pervasive threats and that those threats must be met with violence. The signs go so far as to make mention of shooting people who dare defy property lines. I’ve been personally threatened while walking in Lakeside. Even once while walking with my visibly pregnant wife.

SR: It bears noting that I began this project at a distinct moment in American history: Donald Trump had just been elected. Amidst my own disorientation and disillusionment, I very suddenly understood that I lived in a place that embodied the sort of white paranoia that propelled Trump to office. I couldn’t exactly relate, though. Even though I lived in Lakeside, I felt like an outsider. Usually, I put great effort into being as empathetic, accepting, and welcoming as I can toward everyone. But I think at that moment in my life and in the history of this country, it felt very difficult for me to feel anything but contempt for those who would vote such a truly terrible person into office.

Over time, I came to see that I suffered from much of the same fear and paranoia as my neighbors did, though I also responded to my psychic discord somewhat differently than many of them. I eventually resolved to express compassion for my neighbors, for their common needs, and my solidarity with their shared human experience: no matter their political or ideological orientation. Gotta say, though: that proved to be really difficult.

TLC: That call for empathy and self-reflection is set-up from the start. You begin the book with a Carl Jung quote, “Everything that is unconscious in ourselves we discover in our neighbor, and we treat him accordingly.” What was the impetus to explore this photographically? Was it merely therapeutic or is your hope that art can help address this predicament?

SR: I’m aware that I can personally do little to heal this country’s profound divides, but this I can do: make good and honest work, work that points toward healing. I don’t know how big a role I can ultimately play in making America a healthier place, but something always accomplishes more than nothing, right? Lakeside is an extension of all my previous work — of The Reflection in the Pool, A Glorious Victory, and YAMOTFABAATA. Beyond food and water, empathy may be our most profound common need. I don’t want my viewers to see others in Lakeside; I want them to see their own reflection in these symbolic neighbors and community members. We are all deprived of so much in this hyper-individualistic, anti-communal, Capitalist culture, and most of us respond to these deprivations in ultimately dysfunctional ways. It’s just that each of us can fully and completely justify our own dysfunctional reactions while simultaneously giving others too little, if any, of the same grace.

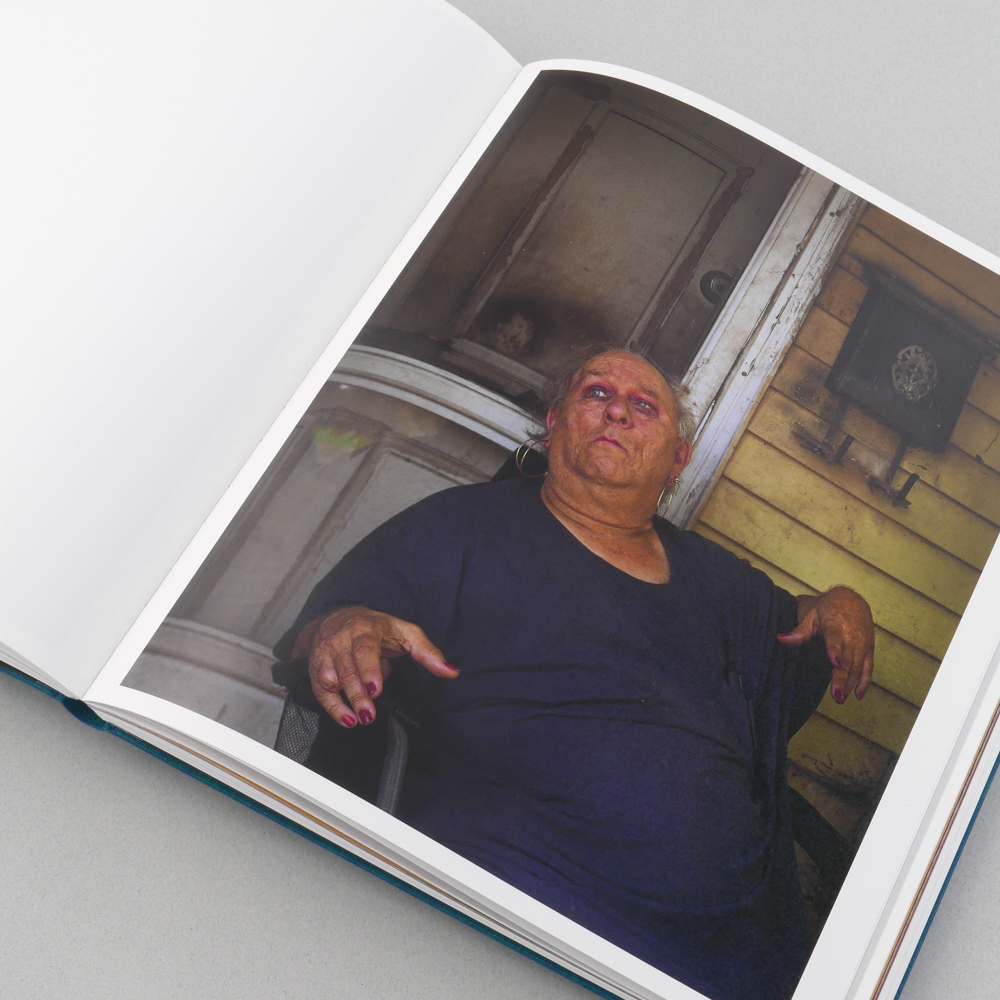

SR: Mostly, I’m mostly looking at older white cis-men in Lakeside, right? Men who the Left often deem the monolithic devils of the Right. I get it. And I also get that there are just really distasteful and destructive people; abusive racists and misogynists, avowed white supremacists, y’know? But aren’t we on the Left also guilty of objectification, demonization, and bias? I’m trying to look at these men in a way that both acknowledges their culpability and recognizes that those destructive identifications and reactions arise out of this deep need for something that they’re just not getting. Afterall, they’re also part of this inhuman system. And that’s radical empathy, right?

The way we as a culture, at least those of us on the Left, often stereotype old white guys: it’s only going to exacerbate our national problems. I know that’s much easier for me to say than it might be for someone in the crosshairs of the patriarchy; and I know it’s not a popular opinion. But, I also know in my heart that it’s likely true. The vast majority of us — all creeds and orientations and colors — share a common enemy, and that enemy thrives on racism, sexism, classism, LGBTQ-phobia, economic misdirection, and the like; supremacy is a virus, and it has a source. The Oligarchs and their media barons are tossing us a boat load of red herring to forestall the working class solidarity that might otherwise topple them. I feel profoundly grateful that I’ve not fully surrendered to the paranoia and intra class violence this propaganda is designed to enflame. But it really is a lot of work, and I don’t always succeed.

SR: And look, I understand that we can’t all give compassion to everyone. But please take note that compassion and understanding are possible even when it seems least probable. There’s so much power in that. If someone can’t give compassion to the men of Lakeside, that’s okay. Perhaps give yours to someone else who might be in need of it? Give it to prisoners, perhaps? Or to your boss who might feel

just as stuck in an exploitative system as you do? The point is: find a way to give more compassion, especially where it’s often missing. My idealist side says, maybe then this country might still have a chance?

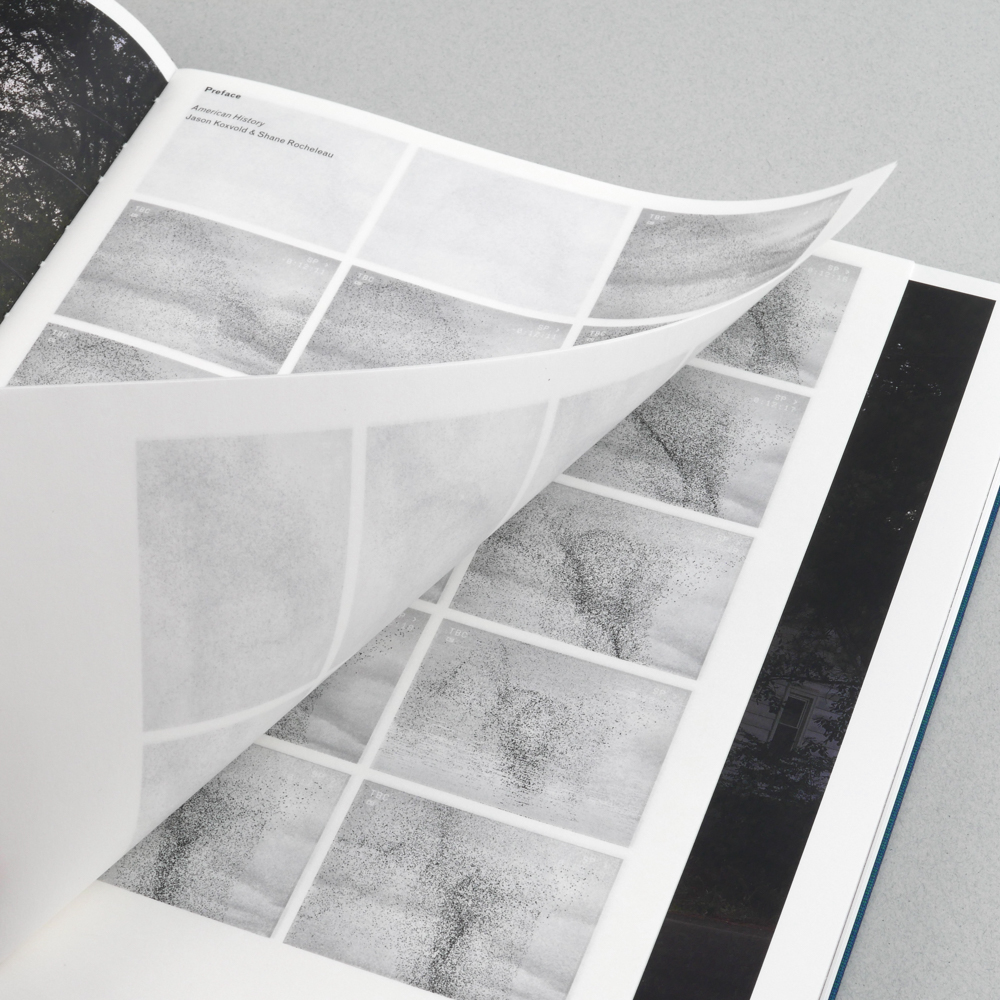

TLC: The first photograph in the book is of a neighborhood home in Lakeside, but that image is interrupted. There is a visual essay depicting the flight patterns of a flock of birds. A murmuration.

SR: Yes. We start with a view of a generic little house which serves as a symbol of the American middle class. And it is terminally interrupted by a visual essay entitled American History. On the one hand you’re seeing this murmuration which can appear rather beautiful, right? Just like the conventional telling of American history can appear rather beautiful. If you’re not careful it will interrupt your ability to see clearly what it is we actually have here in the U.S: a unilaterally militant and violent settler colonialist and imperialist power that is failing its own people and exploiting nearly everyone and everything on the planet.

SR: In this murmuration of Starlings, we have a gorgeous group performance. But what’s really peculiar is that, in reality, each bird is actually only aware of just a few other birds: like a group of marching soldiers. These individuals are impacted and shaped by their immediate neighbors, just like we often are; but they also each give shape. I’m not sure how good any of us is at seeing the ways we are shaped by our country, but I think we’re worse at understanding how our hyper-local behaviors have national consequences, give shape to much bigger things. Everything we each do is both shaped and gives shape. So, for me, I go back to compassion. What kind of shape do I want to create? I think there’s power here, and I want to use it intentionally. I want to be better than my country has taught me to be

and way, way better than its example.

Additionally, the birds depicted, European Starlings, are an invasive species. They were brought here from Europe and their population grew to large numbers — from 100 or so individuals to over 200 million in barely more than a century. They push out native species, raid nests and take them over as their own. It’s a perfect metaphor for settler colonialist America, a country that has committed genocide

against this land’s indigenous peoples, even if, individually, it may be difficult to truly appreciate our respective roles in this vast and ongoing historical crime.

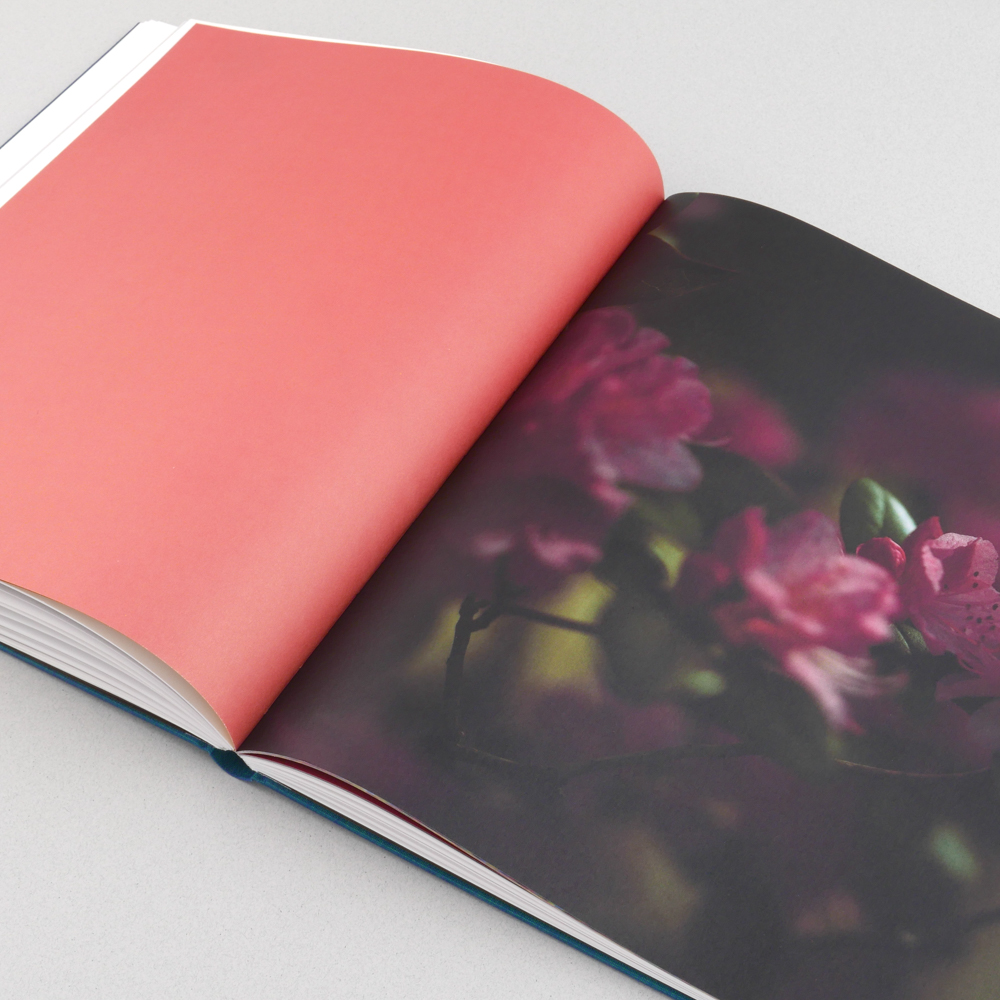

TLC: Yes, you have depictions of the Starling’s destruction. I’m thinking of the broken eggs from the raided nest of a woodpecker. Nature can be brutal, but as you mention, also beautiful. That seems to be a theme throughout this work.

SR: When you get to those beautiful pictures of nature, I want you to sit in reverie. But if you spend time with the field notes near the end of the book, you’ll learn that many of those beautiful plants are invasive species. I’m trying to force myself to contend with something that’s more complicated and to understand that to be fully human is to hold and appreciate many conflicting truths all at once.

TLC: Everything is not always simple. Or clear. Some of your portraits are completely out of focus. Canyou talk about that choice?

SR: It’s about looking, right? But it’s also about understanding that you’re never going to see it all. Maybe I am suggesting you can never focus or resolve enough to actually get the full picture; there’s always more like in those children’s books that zoom in and in and then zoom in yet more. In these out of focus pictures, the labels and identifying qualities become moot. All you can recognize is the human

figure. There’s an opportunity to see the need to refocus and reframe, to be more humble and to gain new clarity. Maybe it’s in these pictures where Jung’s quote at the beginning of Lakeside makes most sense?

TLC: Change is the only constant. That seems to be reflected in the chapter heads of Lakeside. Can you talk about the artifacts depicted on each title page.

SR: So we start with the tooth of a Megalodon shark — which millions of years ago swam above where I’m right now sitting. The next chapter is the partial tooth of a Mastodon, followed by Indigenous spearheads and an arrowhead. The teeth are the violent tools of the past, each made obsolete by what comes after. And today, through violent replacement, the Indigenous people of Lakeside – the Chickahominy – have been largely relegated to artifacts, just as the teeth became fossils. The last chapter depicts a handgun’s trigger, which is me now looking into the future. This culture that we’re told is the greatest ever: most of us can’t imagine that it will ever fall. Of course, it’s not the greatest ever: there’s no such thing. And it will fall. We are all subject to the same laws of nature.

Lakeside by Shane Rocheleau is published by Gnomic Book and includes a visual essay by Rocheleau and Jason Koxvold. The photobook is available for purchase through Gnomic Book’s website.

Shane Rocheleau is an American photographer whose work confronts the endemic position of toxic masculinity and white supremacy within the American experience. His work has been exhibited in the United States, Spain, Russia, Brazil, Australia, Ukraine, The United Kingdom, India, and Germany, and his photographs have been featured in a wide variety of online and print publications, including Aperture’s The PhotoBook Review, Dear Dave Magazine, The Heavy Collective, Paper Journal, and The Washington Post. Rocheleau’s three monographs – You Are Masters Of The Fish And Birds And All The Animals (2018), The Reflection In The Pool (2019), and Lakeside (2022) – are published by Gnomic Book and variously collected by the Museum of Modern Art, the Vogue Italia Collection, Fondazione Teatro Regio di Parma, and Tate Britain, amongst others. Rocheleau lives and works in Richmond, Virginia.

Rocheleau was just name a 2023 Guggenheim Fellow.

Follow Shane Rocheleau on Instagram: @shanerocheleau

Gnomic Book is an independent fine art imprint founded in 2016 and based in Portland, OR, with a focus on developing challenging projects by emerging artists in small, high-quality editions that explore the notion of book as object. Three Gnomic projects have been shortlisted for the Aperture / Paris Photo First Book Awards, and all of our books, present and future, are collected by the MoMA Library.

Follow Gnomic Book on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

Jamel Shabazz: Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025December 26th, 2025

-

Andrew Lichtenstein: This Short Life: Photojournalism as Resistance and ConcernDecember 21st, 2025