Takako Kido: Skinship

This week have been looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Takako Kido and I discuss Skinship.

Takako Kido was born in Japan in 1970. She received a B.A. in Economics from SokaUniversity in Japan in 1993 and graduated from ICP full-time program in 2003. She has exhibited work in solo and group exhibitions internationally including Foley Gallery in New York, Sprengel Museum Hannover in Germany, Noam Gallery in Korea, Newspace Center for Photography in Oregon, Sendai City Museum in Japan. Her work has also been featured in publications and web magazines internationally. She was one of a Photolucida Critical Mass 2021 Top 50 photographers and also a finalist of GommaPhotography Grant 2021. In 2022, she received a grant from Women Photograph and was awarded the LensCulture Summer Open 2022 winner. She is currently based in her hometown, Kochi in Japan.

Skinship

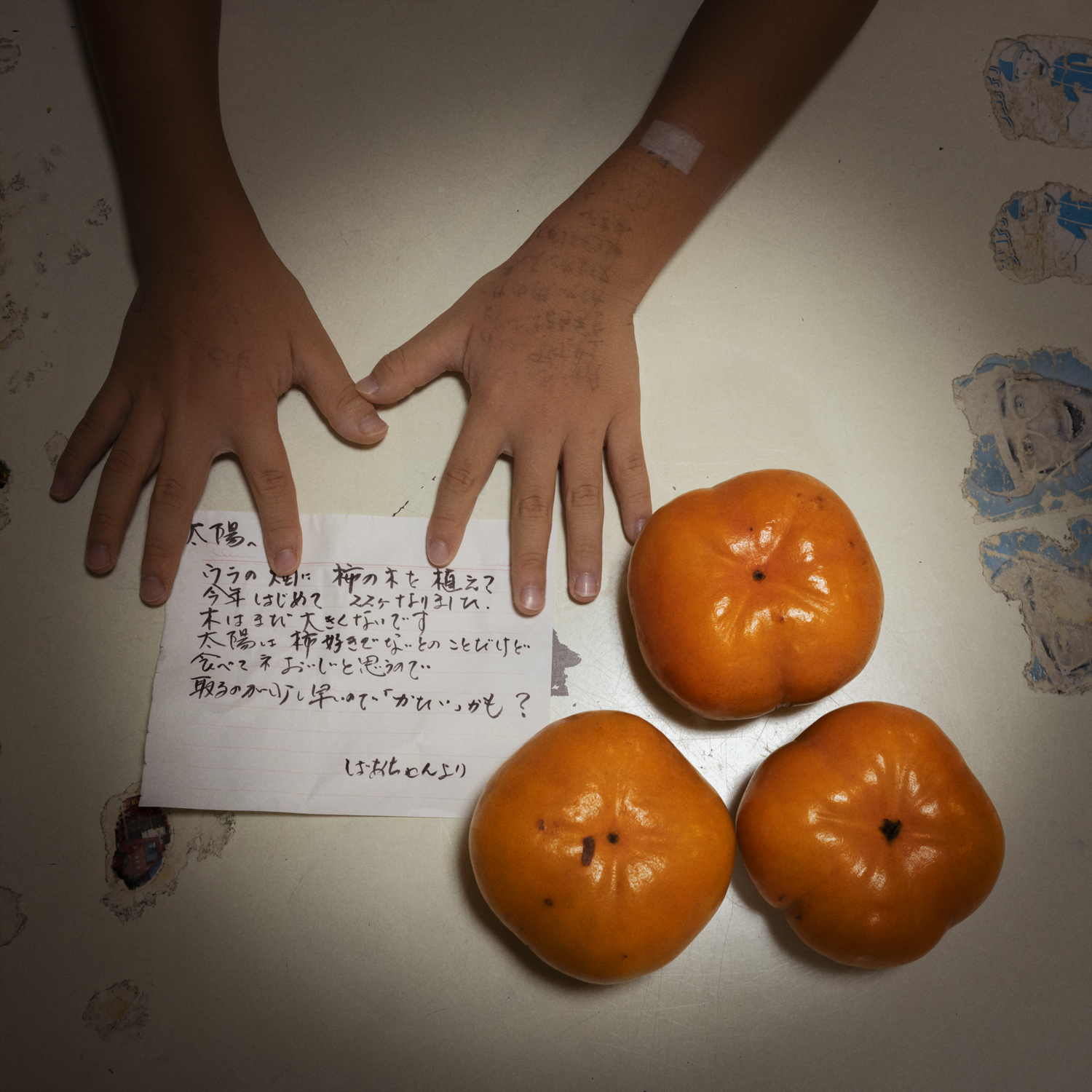

Skinship is a Japanese word that describes the skin-to-skin, heart-to-heart relationship between a mother and a child or family. It includes various forms of closeness; holding hands, cuddling, carrying a child on the back, breastfeeding, co-bathing, co-sleeping and even just playing together, anything which build intimacy. Through an experience of loving touch, a child learns to care for others. Japanese skinship is considered to be important for strengthening the bond of family and also for the child’s healthy development.

Because the idea of skinship was perfectly natural to me as Japanese, it was only after I was arrested in New York due to the family snapshots of skinship, did I realize how unique and shocking it could be in other cultural contexts. Living in both Japan and America showed me a clear cultural comparison and paradox.

Back in Japan, I gave birth to my son in 2012. There was no boundary between our bodies; a symbiotic union. There was a feeling of oneness. Somehow I started making self-portraits amidst the chaos of everyday life. Photographing my son growing up and enjoying skinship also enabled healing my old wound.

Child-rearing is new and nostalgic at the same time. As I parent my child, I re-experience my own childhood, which is both happy and sad. As I see my son grows, I accept my aging and realize it’s not long until I have to say goodbye to my parents. When I was a kid, my late beloved grandmother told me when she saw me cry at the idea of her death that I would be ok because we would go in order. I couldn’t accept it at that time. But now as a mother, I understand what my grandmother told me and the cycle of life and death.

Daniel George: You wrote that this project started off naturally, “amidst the chaos of everyday life.” Would you talk more about its development? At what point did you realize that this was becoming something purposeful?

Takako Kido: After my son was born, I breastfed him every one and a half hours day and night. I was exhausted, overwhelmed by the reality of child-rearing and totally forgot I was a photographer for a while. But around when my son turned 11 months, I suddenly realized I had to photograph this great moment of breastfeeding! Then I made the first self-portrait of breastfeeding with my Rolliflex. It wasn’t easy. I set my rolleiflex on a tripod, used a long shutter release, sat on a futon and hid the release cord under the futon, breastfed my baby and made a picture. Then, I put my son on the futon, went to my Rollei to wind the film, got back to my son to breastfeed and made a picture again. Eventually I asked other family members to push the shutter release. I didn’t have time to scan, work with Photoshop, nor print. So, I kept dropping off my film to the photo lab for the development and accumulated developed color negatives. I knew this work was important when I made the first image, or even before because I was arrested in NY due to the family snapshot of skin-to-skin communication and the nakedness within family. As I breastfed my son, I deeply felt there was no boundary between our bodies. Instead, the feeling of oneness was there. I experienced skin-to-skin relationship was just the right thing for us. I knew I had to speak up though I didn’t have the theme or concept of “Skinship” yet.

DG: I was initially drawn to your photographs because of your refined visual sensibilities, but I feel their strength is in their sincerity—particularly regarding themes of familial relationships. What led you to expand this work beyond self-portraits to include depictions of other family members?

TK: At the beginning, I was making breastfeeding self-portraits only. When I tried to take pictures of my son, he was curious about my Rolleiflex and came to touch the lens. So, I became a cellphone photographer when I took pictures of my baby. Only the pictures I could make with my Rollei was breastfeeding self-portraits because he concentrated to breastfeeding. And I naturally started taking pictures of other family members. Because when they were taking care of my baby, I could take pictures. After my son started going to kindergarten, I started scanning, printing and editing then eventually I felt getting stuck. I was not sure whether I should show only breastfeeding pictures or I should mix breastfeeding and other family pictures together. Then, in the end of 2020, I found the Exhibition Lab workshop which Michael Foley was doing with Elinor Carucci. Lucky for me, all the classes were held online because of pandemic. Through the critique classes and rewriting my artist statement again and again, I came to know I was taking pictures of skinship and finally came up with the title “Skinship”.

DG: And how did your son and other family members respond to the presence of the camera? How did you navigate that inherent collaborative process?

TK: I have been taking pictures at home and outside home for a long time since I was a teenager. So, for my family, it is natural that I take pictures of them. I didn’t ask them for the collaboration nor explain about my project. My husband knows what I am doing and how important this project is. My son grew up with being photographed. My parents don’t know what exactly I am doing but they know how much I want to make pictures. So, they just let me photograph most of the time. My photo-shoot starts when I find something or when the light is beautiful. Sometimes I take pictures of what is going on, another times I try to create certain scenes. I ask them “Let’s take pictures over there because the light is beautiful now.” I have a list of what I want to make.

DG: In your statement you highlight a contrast between cultures—how in the United States this type of work might be considered more intimate/private, whereas in Japan it is perfectly natural. What was the process of reconciling these differences as you selected images to exhibit and share?

TK: People in the United States focus on the nudity of a child, the nakedness within family, extended-breastfeeding and skin-to-skin contact. I have received many different comments from “Your work has challenged how I view the skin contact. It made me think a lot.” to “It is creepy. You are perverted. Get the treatment.” I really hope we could understand each other’s differences.

For Japanese people, the nakedness within family and skin-to-skin relationship is everyday thing probably because we co-bathe and co-sleep. It’s nothing special. But it is intimate and private for Japanese, too because it is something we do at home. Japanese have “Honne” and “Tatemae”. “Honne” is one’s true feelings not showed to others. Japanese behave and speak with “Honne” at home or with close friends. “Tatemae” is the communication style in the public eye like at school, at work, etc. Skinship is one of “Honne” things at home. I think that is why skinship has not been known nor shown much in the western countries. I am one of rare people living mostly with “Honne” in Japan probably because I am an artist and I lived in NY.

The focus of Japanese is on me, as a wife and a mother, being naked in pictures. It is a kind of scandalous thing in Japanese patriarchal society. My husband received a call from his brother who hadn’t called him for years. His brother said “Do you know your wife is showing her naked pictures on the social media?” My husband just said “Yes.” My hope to Japanese is to realize the uniqueness of skinship, and to appreciate the benefit of skinship and our own traditional child-rearing way. Otherwise, skinship might be disappeared before we knew it since Japan keeps Americanizing.

So, I have messages to both cultures. When I edit, I select and sequence images very carefully so that I can convey how we are feeling when we skinship in order to show something universal like warmth, tenderness, the feeling of security, intimacy and love. At the same time, the focus or interest from both cultures co-exist in my work. So, I think I can show same images in both cultures.

DG: Also, I can’t help but ask about the arrest. Would you mind sharing what that was all about?

TK: Ok, no problem.

Back in 2007, my husband and I (he was my boyfriend at that time) were living in NY. His son from his previous marriage came to visit us from Japan during his summer break. After spending one month with us, He said he wanted to live with us. He was 10 at that time. His mother in Japan said OK about it, we said OK about it, and we started living together in NY. We were becoming a family and getting closer. We co-bathed, co-sleeped and he started running around naked at home like a typical Japanese boy and said “Take a picture!” and I took pictures by my point-and-shoot camera with a color negative in it. He learned how to use a tripod and self-timer, and took self-portraits of us being naked in the bedroom after taking a bath in hot summer. I didn’t even remember what he photographed. At that time, I was working on my own project with Rolleiflex and B&W negatives. I developed B&W by myself but it was a color negative and also it was just family snapshots not my artwork. I dropped it off at the drug store without thinking well. When I went to pick it up with the boy, I was arrested.

At the beginning of Skinship project, I was trying to talk about my work without talking about the arrest. But after rewriting my artist statement again and again, I realized I should write about it in my statement. Otherwise, I couldn’t explain why I started and what made me realize skinship was unique. I faced what happened in NY. That was the turning point of my project and myself also. What I want to say became clearer and images started becoming stronger. Also it enabled healing my old wound.

DG: You mention that as a mother, you now better understand conversations that you had with your grandmother on life and death. For me, the photo Umbilical Cord (among others) references this theme in a lovely, subtle manner. How do you feel your photographs, and this project as a whole, engage this dialogue?

TK: In my project, life and death is seen off and on because it is in our everyday life. As I work on this project, I look at my son growing up. I had my son when I was 41. My son is growing up means I and my husband are getting old. Of course I don’t like feeling getting old, looking at my gray hairs, and my wrinkle. But when I look at my son’s happy face, I can accept my aging and mortality. And I feel I don’t need to attach looking young. It’s a complicated but peaceful feeling. In the picture in which I wear rings on both hands, I try to express my aging. I titled this image “Did I get fat?” The ring on my left hand is an engagement ring from my husband which doesn’t fit my finger anymore and the ring on my right hand is the Origami ring from my son. I got fat after I had a child.

There is a picture in which my son is carrying my mother on his back. He is growing up and my mother is getting old and smaller. In the background, the cherry blossoms are in full bloom. For Japanese, cherry blossoms are a symbolic flower of the spring, new beginnings and the transience of human existence. There is also a picture that my son and my father sitting together half naked on the bed. Looking at the closeness of my son and my parents makes me smile but at the same time, I can’t help thinking that it’s not long until I have to say goodbye to my parents. It is sad but we will all die someday for sure. So, if we could die from older to younger, it’s good.

About the picture, Umbilical cord, the left one connected me and my mother and the right one connected me and my son. The picture is about 3 generations. Japanese women traditionally keep umbilical cord throughout life. It’s a part of my body which is completely dead, like mummy. It’s a little creepy and yes, it’s life and death. But it also shows the feeling of caring about a child and love.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026