Rachel Demy: between, everywhere

© 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC. , cover for between, everywhere

To be a tour manager and a photographer is to be attuned to the slightest of details. The exact time every band member needs to be on stage for sound check; ensuring that every piece of gear is on the tour bus at the end of the night. The exact slant of light; what’s included (or excluded) in the frame. It is no surprise then, that Rachel Demy excels at both.

I’m pretty sure I first came across Rachel’s work on Instagram. We had a number of mutual friends in common, plus a shared background working in the music industry, but it was her photographs that prompted me to reach out, asking her to be a guest on my podcast. We became friends. She released her first book. And my admiration for her work has only grown.

Between, Everywhere is the culmination of Demy’s photographs made while on the road, over a five-year-period, with the American Rock band Death Cab for Cutie. Demy’s black and white photographs capture everything from fan’s expressions, to the shiny moments on stage, to the raw ones off-stage. Demy writes beautifully about life on the road, dispelling the glamor and leaning into the quiet beauty behind-the-scenes, the moments in-between. Between, Everywhere has been recently published by Minor Matters Books. It is available for purchase at Minor Matters, Photo Eye, Elliott Bay Book Co. (Seattle, WA), Strand (New York, NY), SubPop @ Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (Seattle, WA), and HHV Handels (Berlin, DE).

I recently interviewed Rachel via email where she talks about what it’s like to photograph on tour, moving from film to digital, the process of editing Between, Everywhere, what she’s currently working on and more!

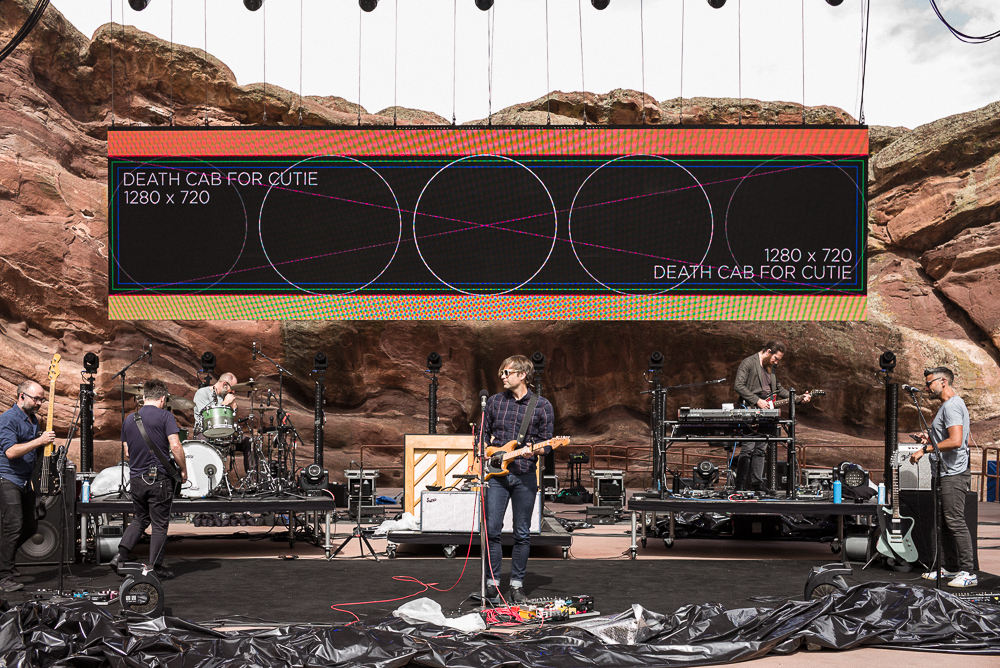

Soundcheck, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Between, Everywhere

Between, Everywhere is the culmination of my experience as a photographer, professional tour manager, and Death Cab for Cutie family member. This book is about a band, but more specifically, a band on tour. Tour is something I know a lot about.

I’ve encountered a lot of people who assume touring is chaotic, or worse, glamorous. Most of the time it’s neither. Being on tour means being suspended between two worlds, between different versions of home. Like color, people can see the same tour differently.

Tour is a bizarre construct. Its absurdity hides in plain sight. If you squint and cross your eyes, it looks totally normal, a simulacrum of home, and you get that warm sense of being anchored somewhere—even if it’s no particular place at all.

Like standing still on a comet.

I find the monotony of tour compelling; its repetition meditative; its structure comforting. I continue to be intrigued by how others carve out privacy and quietude within the confines of this communal, nomadic environment.

My roles within the Death Cab ecosystem have transformed many times over the two decades that I’ve been around. This band cements for me not only what family means, but what family does. I’ve been so many different versions of myself with them, and they’ve welcomed me in, again and again—with a hug, a laminate, and a bunk on the bus. – Rachel Demy

Load-in, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Montserrat A. Carty: Let’s start by talking about the making of the images, and, the making of the book. When you first began making these photographs on the road did you imagine they would become a book? What was your process for selecting and then sequencing?

Rachel Demy: When I started making this work, I never in my wildest dreams thought I would eventually make a book. When I began touring with Death Cab in early 2015, I had just left my career in tour management (and more) that previous December. I was burnt out. Ben and I had been dating for two years, both of us touring separately. In order to take our relationship to “the next level,” we needed to spend more time together. With the band’s blessing, I jumped on the bus and immediately gave myself a job. I had been photographing live shows and the mundane details of tour for almost a decade, alongside my job as a tour manager. I was not accustomed to being on tour in an unofficial capacity, especially as the romantic partner of one of the band members. I’d been touring long enough to know it’s not good for me to be stuck in tiny rooms with no purpose. Since Death Cab didn’t have much of a presence on social media at the time, I started documenting their day-to-day for that purpose—and also as a way to sing for my supper/bunk on the bus.

Up until that point, I had only worked with film which, while beautiful, is too expensive, impractical, and slow for the pace of tour and social media. To say nothing of navigating international airports and language barriers with a lead bag full of exposed film. So, I got my first digital camera and it became a 4-year-long crash course in learning how to shoot and process digital images. It was messy. Some of those earlier photographs from 2015 and 2016 were rife with amateur mistakes, but there’s a looseness about them that I don’t know if I could recreate now, as a more experienced photographer. Looking back, I think if I had any intention of making this body of work in an official capacity, I would have choked. It wouldn’t have felt as low-pressure or playful. It’s not to say the work itself is playful, but because I wasn’t putting an insane amount of pressure on myself, I was able to connect more deeply with the band, gain their trust, and experiment. I didn’t have any previous experience of working intentionally, either with a preconceived narrative or, for that matter, any long-term project. In fact, I had never taken a photography class until I applied to art school in 2017. So, most of the work in the book is instinctual, anchored by years of experience touring, and knowing this one particular band since 2005.

Whittling thousands of photographs down to about 80 was a long, arduous process. In 2017, I was accepted to the Certificate in Fine Art program at the Photographic Center NW, in Seattle, WA. It was during one of my intro classes in April 2018 that I first shared these photographs, and mumbled out loud, “I think… I want to make… a book?” So I began working on editing and sequencing hundreds of photographs in classes like this, getting feedback from others, while also taking quarters off to go on tour and continue shooting. It was through sharing this work with a few faculty members that I was introduced to our then-executive Director, Michelle Dunn Marsh, who happened to run a publishing house, Minor Matters. She offered to look at my photos—more as a mentor than anything—and I told her I’d take her up on it as soon as I had something worth looking at. Then came March 2020. Lockdown provided a lot of extra time and this would-be book kept haunting me like a deranged ghost. Since there was no more tour, and I felt I had reached the end of what I was capable of making with the guys, I spent an entire year moving shitty little laserjet prints around on my studio floor, trying to figure out how they worked together. I might have had to employ a few weed rice krispie treats in the process. Nobody can say for sure.

Once I got fed up staring at this pile of prints, taking this edit as far as I could by myself, I put together a maquette and reached out to a few people who had offered to look at the work, including Michelle, in March 2021. She insisted this potential book wasn’t just about a band, Death Cab specifically, but was really more about touring in general. Together, she and I made a more concise edit that reflects not only Death Cab 2.0, but also my perspective as a photographer, writer, professional roadie, and wife of the lead singer. It was important to me that the sequence convey tour’s unique loss of time and place, as well as the repetitive nature of tour—travel, mundane daily details, live show, comedown—over and over again. I think we did so pretty successfully. A year later, in March 2022, we announced Between, Everywhere for presale, reached our presale goal of 500 books in 12 hours, and released the finished book in December 2022—eight years from when I began making this work. There are so many full-circle moments in this story, but the most recent is that I am currently teaching the same introductory class in which I first decided to share this work back in April 2018. Life is fun.

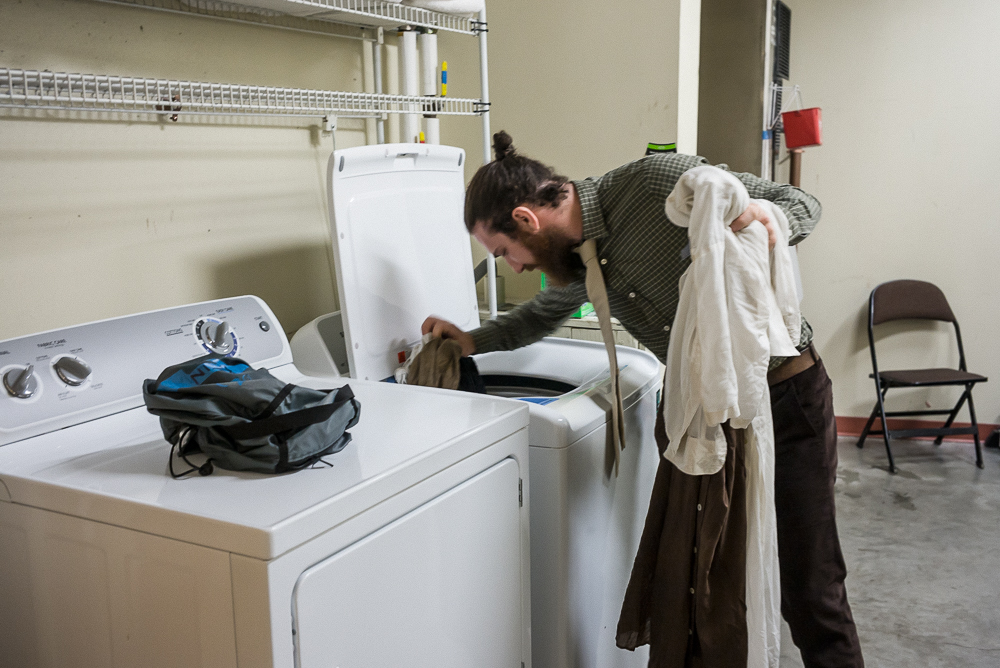

Laundry, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

MAC: People, you write, “burn out at the intersection of spectacle and loneliness on tour.” Musicians often refer to the come down following a tour as “post-tour depression.” As a photographer, do you think there is an equivalent? Post-project depression?

RD: There’s definitely post-project depression. There’s also post-tour-photo-project depression. I’m gonna have a little real talk here, because, well, this is who I am. When we announced Between, Everywhere for presale, I was also in the last quarter of my certificate program at PCNW. I was in the process of finishing my photographic thesis, House Riddled, about the trauma and grief of losing my father when I was five years old. So in June 2022, I graduated, exhibited House Riddled, sent in the final images and text for Between, Everywhere, AND turned 40—all within a few weeks of each other. For the record, I don’t recommend anyone do this. I left for a few months of travel to “celebrate” my accomplishments, and while I did do some celebrating, it was an incredibly difficult period of processing: first, the completion of two deeply meaningful long-term projects, but second, the unexpected emotional backlog. Decades of old, untended grief these projects had uncovered, that I had no time to acknowledge because of the intense deadlines I had to meet. And then suddenly, it was all over. It felt like hitting a brick wall at 90 miles an hour. The clarity of purpose, focus, routine, community, and structures that supported me while I birthed these projects were gone. No school. No work. No familiarity. Just feelings. Just me, and an entire summer of randomly crying in public. I can kind of laugh about it now, almost ten months later, but honestly I think I’m still trying to right myself after this last year. It’s required a lot of vulnerability, acceptance, patience, and, oh man, all of my friends. I’m so lucky to have them. So yeah, post-tour, post-project, whatever. Being on the other side of the finish line can be really difficult.

Suitcases in the Bay, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

MAC: In these photos we feel the crossover of fine art and documentary photography. When you were making the images was this a conscious decision or did you just make the work you were called to make in the moment? How important is labeling genre to you?

RD: I don’t think I’m alone in this, but personally, I find locating my work in any one specific genre really difficult. I like to shoot many different kinds of subject matter in whatever way feels appropriate for the image. I hesitate to call my Death Cab photos “documentary” because I’m not a photojournalist working for a publication, nor do I believe “documentary” is synonymous with “truth.” If we define “fine art” as photographs that convey a concept, feeling, or artistic vision, that contain layers of meaning, then I think there’s a lot of commercial and documentary photography that meets that criteria. I honestly don’t think I’m smart enough to take on this debate!

Suffice it to say, when making photographs, I don’t find genres important at all. It’s only when talking to non-photographers about my work that there’s a pressure to reach for genres as shorthand. Honestly, the only time I employ them is when I want to change the subject. I think most people just want to hear “weddings” or something they recognize as useful and relatable. If you say “fine art,” you’re in for an hour of explaining the ins-and-outs of your creative neuroses to strangers who were just trying to be polite.

Me, in June 2022: “I’m a fine art photographer. I just made a book about a band you might know, but it’s not really about the band. It’s about creating home in nondescript, liminal, constructed environments. It’s also about family and belonging. Speaking of home and family, I also just made a whole other body of work that contains autobiographical landscape portraits of places I used to live when I was a child (that are definitely not architectural); forensic-style interior shots of a place I never lived, but is evocative of all the apartments I lived in in the 80s that I no longer have access to; as well as, posed studio still lifes of my disembodied hand, interacting with the panda bear I’ve had since my dad died—all to convey the subtle foreboding and loneliness of the aftermath of childhood trauma and grief.” Cool party talk! I’m sure you’re as exhausted reading that as I am having typed it. So, when people ask me what kind of photography I do, I just say “music and documentary,” and hope there are no followup questions. Sometimes I don’t even say “music” because “documentary” is vaguely satisfying to most party-people, which moves things along and allows me to get back to the snack table immediately.

Emergency Exit © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

MAC: There are a few audience shots where the subjects of the photographs, by their gestures and facial expressions, appear to be having vastly different experiences of the same music. I wonder about this in photography as well, how we might read a photograph not necessarily how the artist made it but how we experience it. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this!

RD: That’s an interesting observation. But since I’m teaching a class about visual literacy at the moment, I’m going to tease out a few things, largely semantic. I think what you’re noticing about those audience shots isn’t so much different experiences of the same music, but different ways of outwardly expressing emotion to the same music. Everyone’s experience and emotional terrain could be the same or different, but we don’t really know without asking each one of them. All we’re seeing is what happens when music enters their ears, and sets off the Rube-Goldberg-machine of meaning, emotion, association, memory, physical sensation, etc. All the things music pings in us. Something big might come out the other side. Or nothing might come out. Each of us is a black box. LOL

I only offer this because people used to make comments to me like “Why do you look like you’re having such a bad time?” Or “Why don’t you dance/scream/sing along, etc. like everyone else? Do you not like the music?” And I might be having the best time, knowing every single word, completely in awe of this band I came to see, but I just don’t express it the same way. When I get overwhelmed by emotion and sensory experience (in general, not just at shows), I tend to go inward. I close my eyes; I listen; I engage with memories; I notice when my heart does “the thing”; I notice the knot in the pit of my stomach; whatever. I feel, very deeply and very quietly. It doesn’t mean I’m having a completely different experience than the guy screaming next to me. It just looks different, which feels important to distinguish. We all make a lot of assumptions without realizing it.

None of what the audience is doing, and what we perceive them doing, has a damn thing to do with what the musicians intended when they wrote and recorded the songs for themselves. I’m sure when bands perform songs in a venue, it must be super lame to see someone like me standing there with their eyes closed, completely mute. But if everyone expressed emotion the same way, those front row photographs would be a whole lot less interesting. At least, to me.

Similarly, with photography, I don’t know that we are meant to experience a photograph the way the artist intended it. Or let’s just say, we’re entitled to our own experience with art, period. How art transforms our internal environment is the most magical part of being in its presence. That initial punch to the gut before the rational brain gets involved. But how we “read”, or rather, understand, a photograph, and how engage with it outside of our own experience, must include the artist and their intention if we are to have a meaningful dialogue. Or any opinion, whatsoever. I believe it’s important to do both: have our own experience, and then let the artist/their process/their intention inform, shape, and change how we think about what they made. Let it change how we see. Let it change our reality.

But protecting our own internal experience by resisting understanding is really common. Sometimes experience and understanding can be at odds, and that’s a difficult thing to process. For example, I like the work of many male writers who are notoriously misogynistic. Squaring my love of their art with my beliefs, ideals, and values causes a lot of internal tension. But when in doubt, I always come back to generosity as my guiding force. I fundamentally believe that blindly/stubbornly clinging to my own experience at the expense of the artist’s voice is not in keeping with the spirit of generosity in which the artist shares. To not let them in displays a brittleness of spirit. It doesn’t mean you have to like everything everyone makes. Artists don’t necessarily deserve an A for effort. And it also doesn’t mean what the artist intended will change how you feel about their work. But actively resisting or censoring the artist’s voice in their own work is erasure. They’ve let you in. The least you can do is return the favor, by allowing nuance and understanding to balance the weight of your experience.

Warming Up, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

MAC: Anything you’d like to share about a current or future project?

RD: I’ve already said a lot about both my book and my thesis project, but I’d like to share one last thing. While both bodies of work appear so different (started at different phases in life, different photographic styles, different subject matter, etc.), I was pretty surprised at how much they influenced each other as I worked on them concurrently, especially in the writing. Writing about home, trauma, and grief in House Riddled is how I was able to identify themes of family and ad hoc environments in Between, Everywhere. When I was sequencing the book, I had a lot of questions I couldn’t answer. Why am I so drawn to balance and beauty? What exactly is my aversion to spectacle? Why do I take “quiet” photographs? Why am I so interested in how others carve out personal space in crowded rooms? Why do I take photographs or make a job for myself when I feel claustrophobic or stuck on tour in little rooms? Why am I so spatially aware, paying attention to small details, including where all the exit doors and windows are? On and on.

With time, I was able to recognize House Riddled as the origin story for how I see. Between, Everywhere is not just a book about a band I care about. It’s also a photographic document of my love of touring, which was the antidote I found for feeling stuck and powerless in childhood. It also explains my knack for finding humor in the most absurd situations or smallest details. my escape from the confines of childhood trauma/grief, lifelong intuitive awareness of space, relationship dynamics, attention to detail, and desire to find peace in chaos, as well as belonging. Touring, to me, is freedom in a multitude of forms. Joining the circus was the most life-changing thing I could have done for my childhood self. And leaving the circus was the most life-changing thing I did for my adult self.

Freedom, for me right now, is going for long walks at night and taking photographs along the way. That’s all I’ll say about my future project.

Uniform, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Pre-Show, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Show, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Fans, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Solo, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

The End, © 2022 Rachel Demy. Between, Everywhere by Rachel Demy copyright © 2022 Minor Matters Books LLC.

Rachel Demy (b. 1982, San Diego, CA) is a fine art photographer based in Seattle, Washington. She received her Bachelor of Arts in political science from the University of Portland in 2004. For the following 15 years, she worked for a concert promoter, a booking agent, and finally settled as a tour manager for rock bands, where she honed her skills as a portrait and documentary music photographer. Demy completed her Certificate in Fine Art Photography from Photographic Center Northwest in 2022. Her first photography book, Between, Everywhere—documenting life on tour with Death Cab for Cutie—was released in December 2022 through Minor Matters, with a concurrent exhibition at Leica Bellevue. In her spare time, Demy enjoys long-distance running, travel, spelunking on Wikipedia, night-walks, and taking down oysters by the dozen.

Follow Rachel Demy on Instagram: @racheldemy

Between, Everywhere

Photographs by Rachel Demy with Death Cab for Cutie

9.75 x 13 inches vertical

;

83 black & white and color images

;

128 pages

+ hardcover

;

Photographs and text by Rachel Demy;

Published by Minor Matters, 2022;

ISBN: 978-17356423-45.

About Minor Matters Books

Founded in 2013, Minor Matters is a collaborative publishing platform, making books through the engagement of our international audience. We highlight underrepresented voices in contemporary art, and preserve our present for the future through publishing their work. At Minor Matters, we recognize that significant art and ideas may stay on the fringes without the support of a community. Like us. With you. Everyone who buys our books in pre-sales is listed as a co-publisher—we’re making books together.

@minormattersbooks

Eight-time GRAMMY-nominated rock band DEATH CAB FOR CUTIE formed in Bellingham, WA in 1997. The band is currently comprised of Ben Gibbard (vocals, guitar, piano), Nick Harmer (bass), Dave Depper (guitar, keyboards, vocals), Zac Rae (keyboards, guitar) and Jason McGerr (drums). Over the course of their 25-year career, Death Cab for Cutie has played over 1,100 shows on five continents.

Their tenth full-length album, Asphalt Meadows, released in September, 2022, and is receiving ongoing critical acclaim.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, lead vocalist and guitarist Benjamin Gibbard has helped raise over $250,000 in donations and supplies for various Seattle-area relief organizations via his series of at-home, livestream performances.

In December 2020 the band released The Georgia E.P., featuring covers of iconic artists from that state. Originally offered as a 24-hour Bandcamp exclusive, the E.P. raised over $100,000 for Fair Fight Action, Stacey Abrams’ voting rights organization promoting fair elections around the country through voter education, election reform, and combating voter suppression.

Hear more at deathcabforcutie.com

Montserrat (Montse) Andrée Carty is a writer and visual artist. In addition to writing and making photos, she hosts the podcast Musings of the Artist. She is currently a MFA in Writing candidate at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is the Interviews Editor for Hunger Mountain Review.

@montseandree

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Kinga Owczennikow: Framing the WorldDecember 7th, 2025

-

Richard Renaldi: Billions ServedDecember 6th, 2025

-

Ellen Harasimowicz and Linda Hoffman: In the OrchardDecember 5th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025