Virginia Villacisla: Presencio & The Rural Kids

This week we are looking at the work of artists who submitted projects during our most recent call-for-entries. Today, Virginia Villacisla and I discuss Presencio & The Rural Kids.

Virginia Villacisla was born in Burgos, a medium-sized town in northern Spain. After finishing university, she moved to Madrid to focus on contemporary photography. In 2017, she completed her Master’s in Photography at EFTI (International Center of Photography and Cinema).

Virginia’s personal experiences and the contrast between her rural upbringing and city life inspired her project, ‘Presencio & The Rural Kids.’ This project captures how young people interact with the rural areas they inherit from their parents. Virginia’s work has won awards in photography competitions and been featured in photography festivals and exhibitions across Spain. It has also been published in magazines like EXIT and newspapers like El País Semanal.

Virginia’s photography reflects her unique perspective on her surroundings, blending humor, irony, and a keen exploration of the human experience.

Follow Virginia Villacisla on Instagram: @villacisla

Presencio & The Rural Kids

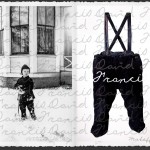

Castilian villages, like most of the villages in Spain, got empty due to the rural exodus to the cities that took place back in the 60s last century. Many villages did not survive to this phenomenon and got totally abandoned. But some others became the perfect place for spending the summer holidays or weekends. The ancient and the modern, the rural and the urban cohabit together through the new generations returning to the village. Thereby, this place, which is their heritage, keeps evolving.

I am the daughter of Jesús, Encarna’s son, but also Tomás’s granddaughter, and the youngest daughter of Tomasita. Presencio is the name of the hamlet where my mother was born (Burgos province, Spain. 200 inhabitants). In Castilian Spanish, Presencio is not only a noun but also the first person of the witness verb in the present tense (I witness). Where people just see a whole of nothing, I see things. And I want to show them.

In villages, there is a family background backing you up. Whether you want or not, you may be part of its history. You belong to the collective mind and it does not matter if people know you by sight or not, they just know that you exist and where you are coming from: “Who your parents are?” Coming from this reflection I am wondering if spaces can disappear. That is to say, do spaces stay in collective memory? Even when they are destroyed? Thereby, I take pictures of the villages where I grew up. These places became other places at the same time because they are the result of many generations that have inhabited them. At the end I find myself in spaces existing in a time with no time, in a place with no place, speaking about people with no people in there. Between progress and the return, I am blindly looking for.

The resulting pictures are the testimony of my dialogue with these spaces (as a young inhabitant). Presencio means summers without law, party lovers, staying up till late at night, drinking and sharing first-time experiences. It is the way in which the youth, while becoming grown-ups with responsibilities, interacts with the rural spaces inherited from their parents. Wilderness, instinctive, passion, and freedom. Presencio means growing up in community in a place stopped in time. A place with no future but that strangely offers some security (because it has always been and will always be there). Something deeply buried with these links coexists with it, with no apparent connection. They are based in an identity, in supporting the memory and the reputation of their ancestors to substitute them. They have to do with a concrete territory: the love for the people from the same place and, at the same time, throwing stones to people from neighboring villages.

Daniel George: Tell us how this project began. What led you photograph the villages where you grew up?

Virginia Villacisla: After completing my higher education in my hometown, I moved to Madrid (capital of Spain) to study a master’s degree in photography (which I had always wanted to study). During the master’s degree tenure (18 months), each student had to develop a personal project to present a selection of pictures at the end of the course serving as final master’s project work. I had just moved to Madrid and I could not find anything personal I could relate with catching enough of my attention to photograph. At first, the big city and the course were quite overwhelming. Feeling so out of place in Madrid generated a need for belonging. Going away helped me to ask myself questions such as being part of something and relating in another way to the spaces in which I had grown up.

I asked myself what lived experiences defined me the most, what it was that I could tell the world from a personal and honest perspective: definitely having grown up in rural Castile had shaped my way of being and understanding what life is about. I have spent every summer of my life and most of the weekends in Presencio (province of Burgos, Castile and Leon, circa 200 inhabitants), the hamlet where my mother was born. That location definitely would be the setting for my photographic project.

DG: You describe these places as feeling “stopped in time.” Do you feel your perception of them has changed as you have lived away from them? How so?

VV: It is precisely because I have lived for a while away from these spaces, I feel that they are somehow stopped in time. They definitely experience some changes: houses are built, roads are fixed, streets are improved… but in essence, this type of places do not change. There are no structural changes: there are hierarchies and traditions that its people maintain. You know people and they know you. They know who your relatives are and all your history. When you walk down the street, the most common thing is for an older person to ask who your parents or grandparents are/were. They acknowledge them, they nod, maybe they ask about them and leave. They basically locate you within the hamlet’s family tree. I think residents of villages enjoy the stability of things; it gives a certain security and peace during times of change and political and economic instability.

DG: You mention the transition that occurred in these places between the 60s and now. Could you describe your interest in focusing on the youth in these areas? What is it about their experience in “the rural spaces inherited by their parents” that you find so fascinating?

VV: I was clear that the setting of my project was going to be the hamlet. At the time of starting, it was common to hear the concept of “Empty Spain” in the media referring to the rural areas. In 2016, an author called Sergio del Molino published a celebrated book that addresses the emptying of these areas (‘La España Vacía’, Turner). Problems that even led to the foundation of very minor political options: Teruel Existe (Teruel Exists), Soria Ya (Soria Now), etc. Abandonment was the prevailing perspective to tell rural Spain to people. Although, unfortunately, it is the reality of many villages, that image did not correspond to my personal experience. In response, I made ‘Presencio & The Rural Kids': from within and showing a different side. The project shows how a gang of kids grow up in a small village and live their first life experiences there: first loves, parties…

I set out to portray a certain era of young people, when they are about to become adults. In some way it made sense to talk about the town through teenagers. Like them, the town found itself in an intermediate place between comeback and progress, childhood-adulthood, old-new.

DG: On your website, you include stories of family interspersed with the images. Why did you feel it was important to include this written component?

VV: As already mentioned, in the images I focused on young people and how they interact with these spaces. However, there was nothing to show who they had inherited them from. Hence, I used the text to describe the family environment in which we all grew up. There are short stories gathering anecdotes or particular dialogues with my grandfather. I think they speak for themselves about the curious Spanish humor, the absurdity, the excessive pragmatism, the economic idiosyncrasy, the social classes, the special personality and spontaneity of the townspeople.

The inclusion of these texts gave me the freedom to portray and approach the space in a fresher way, avoiding merely descriptive shots. The physicality of the town was no longer so important but the character it imprints on its neighbors.

DG: In your artist statement, you write “Where people just see a whole of nothing, I see things. And I want to show them.” I think this epitomizes why many of us are drawn to make photographs—to show, often within the everyday experience, what and how we see. Besides the obvious (subject matter), what do you witness within these places, and how do your photographs reflect this vision?

VV: What I try to capture, above all, is sensations. Being with your friends one afternoon in the pool of laughter, kissing your partner, feeling the heat of the sun on your face, returning home in the car after spending a day swimming in the river. Sensations that we experience every day, little but important. There are no big acts in the photos, they are everyday scenes. The camera allows me to stop and look closely at these moments.

Searching for that feeling of spontaneity or of a photographic diary, I have appropriated the model of amateur representation and parties, especially for the nighttime ones. I love the way they seem chaotic, random, when, in essence, there is a great component of thought and reflection in the shot. When I cut the reality around with my camera, there are some concepts guiding me: the dysfunctional, the absurd, the fragmented and the inhabited.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2024 Lenscratch 1st Place Student Prize Winner: Mosfiqur Rahman JohanJuly 22nd, 2024

-

Ellen Mahaffy: A Life UndoneJuly 4th, 2024

-

Julianne Clark: After MaxineJuly 3rd, 2024

-

Kaitlyn Jo Smith: Super8 (1967-87, 2017), 2017June 30th, 2024

-

Katie Prock: Yesterday We Were GirlsJune 27th, 2024