Native American Heritage Week: Sarah Sense: Hinushi

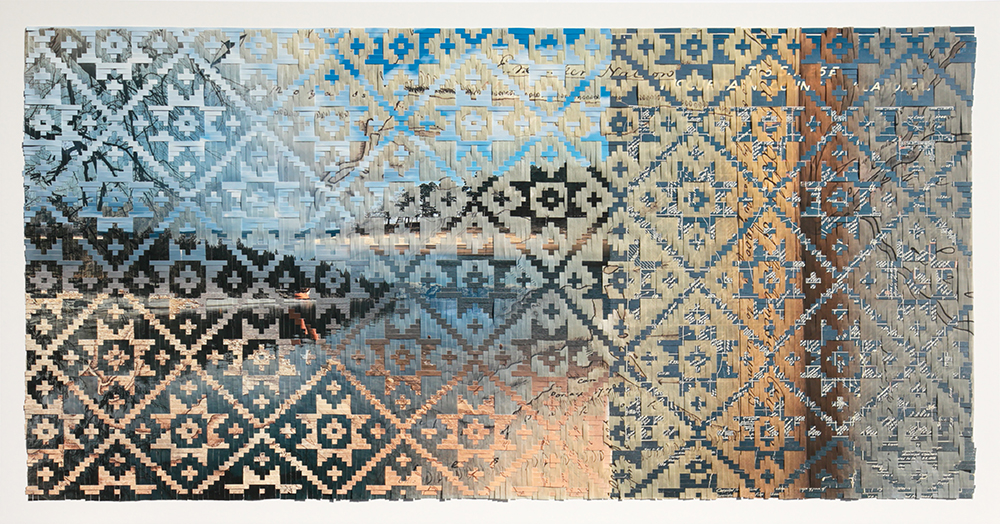

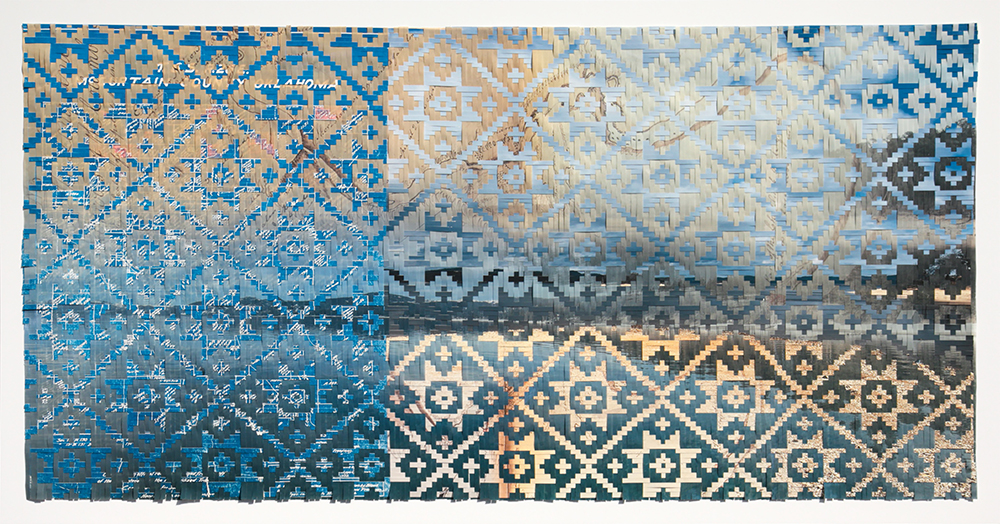

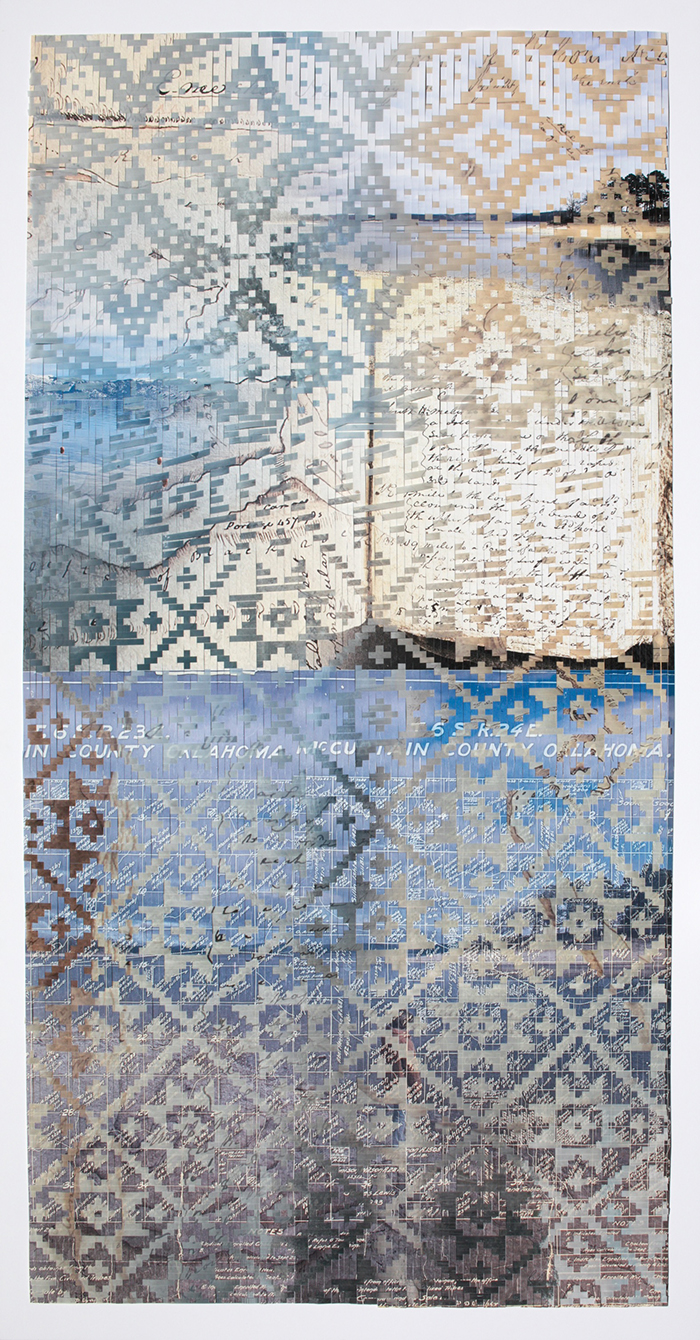

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 1 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) collection of the Choctaw Nation

In honor of Native American Heritage Month, LENSCRATCH sat down with Indigenous lens-based artist Sarah Sense to discuss her new series, Hinushi. This work is currently on view at the Griffin Museum Virtual Gallery and at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890-Now exhibition. Sense will be In Conversation with Marina Tyquiengco through the Griffin Museum on Monday evening from 7 -8:30 EST.

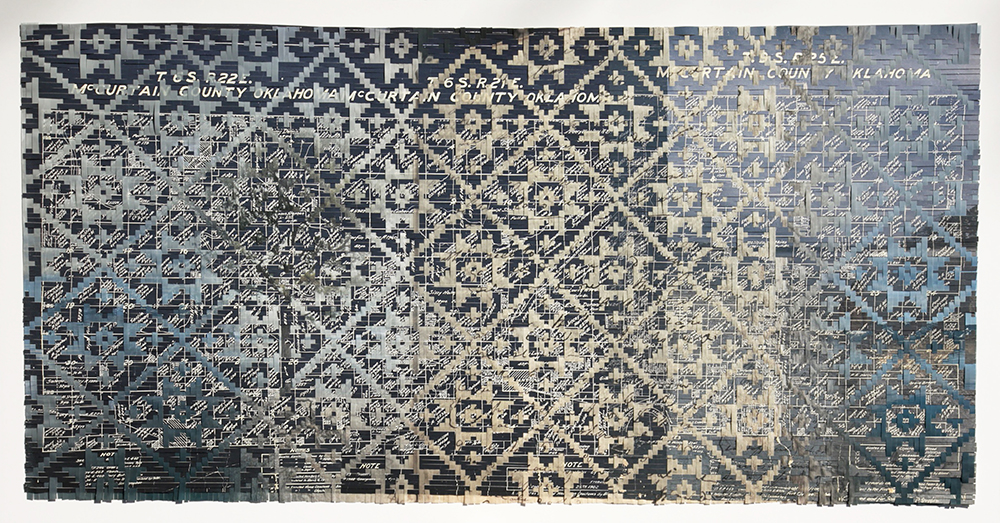

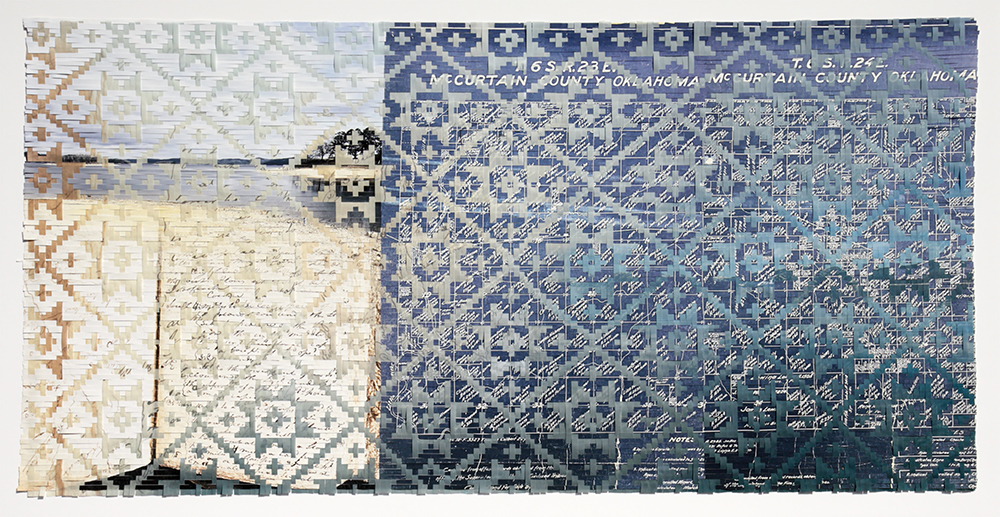

Hinushi is a series of landscape photographs from ancestral homelands woven through colonial maps of the Mississippi River, Gulf of Mexico, and Choctaw allotment land. The blue allotment maps of McCurtain County, Oklahoma (1902, courtesy of the Choctaw Cultural Center) were created after the United States Indian Removal Act (1830). Each drawn parcel indicates allotted land for individual Choctaw Tribal members and includes their name, blood quantum, and age, serving as a government document and form of assimilation into the colonial structure of land ownership, further displacing cultural values and land connectivity. After removal from their ancestral land, Choctaws suffered a long walk to “Indian Territory” or what is now called Oklahoma. Woven together are maps from Oil News (1920, from my research at the British Library, London, England) woven through Broken Bow landscapes, where our family was relocated. Choctaw basket patterns from my Grandma Chillie’s basket of sun and stars are woven through these maps, joining the land with the colonial maps as an act of reclamation. The journaling and mapping are photographs of Lewis and Clark journals taken during my archive research at the St. Louis Historical Society. The Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery Expedition (1804-1806) was funded by the United States government and initiated by Thomas Jefferson after the Louisiana Purchase (1803). These colonial forms of exploring, discovering, and mapping are constructed to manage land and people. The colonial mapping and government allotment structures represent established spaces. Weaving Chitimacha and Choctaw patterns through the maps reclaims space.

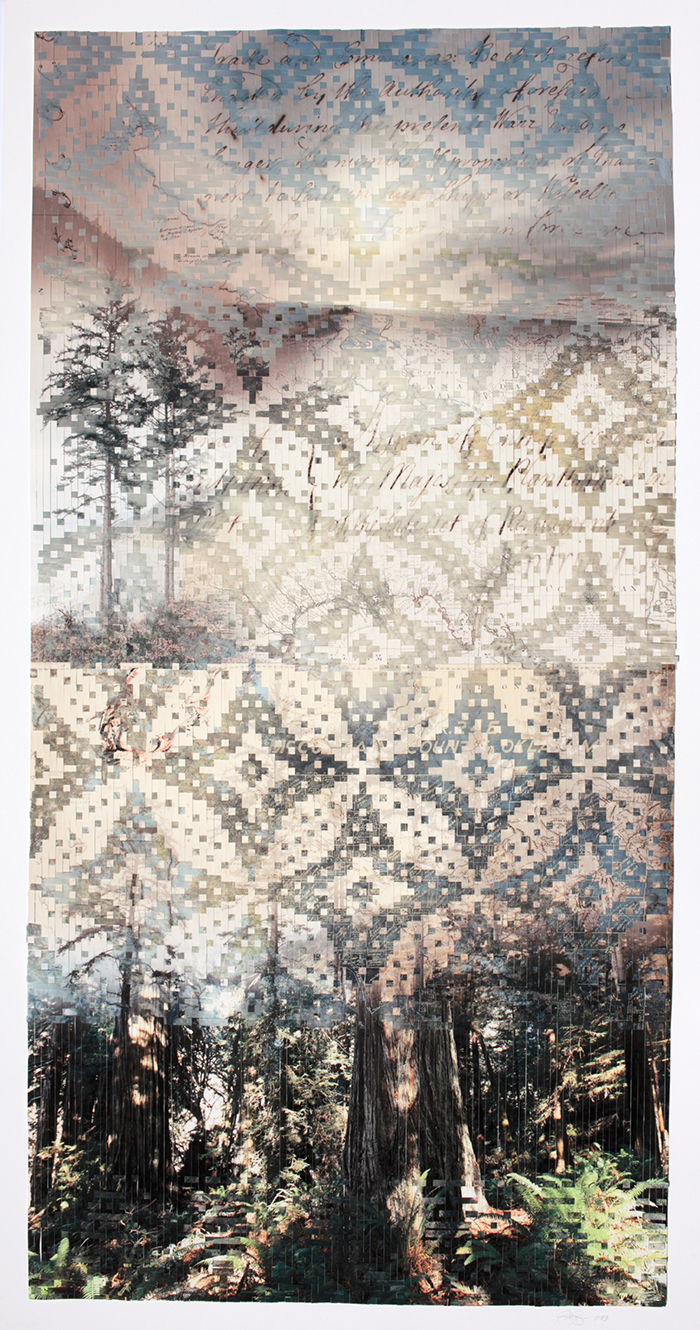

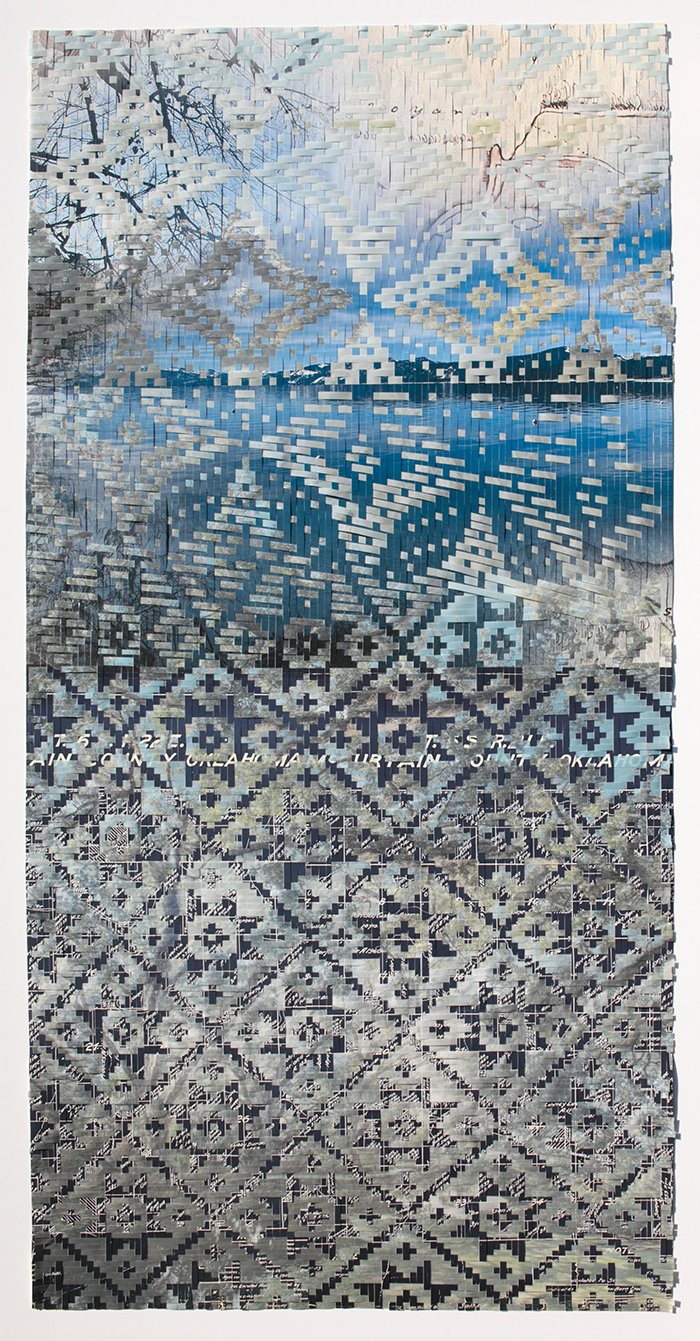

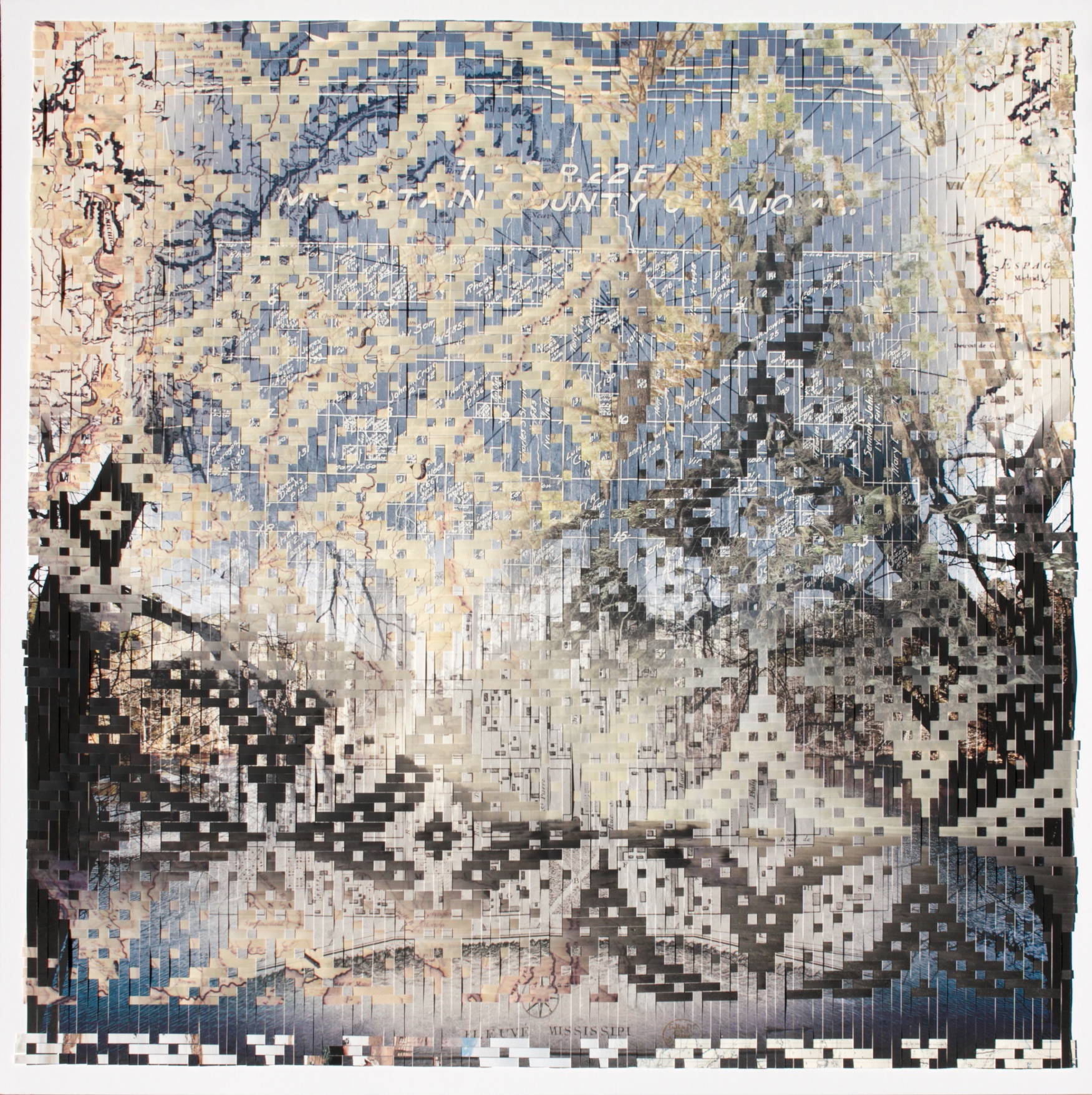

The trunks of Coastal Redwoods from California and Live Oak Trees from Avery Island, Louisiana, sit on top of the roots with maps from Lewis and Clark’s journals laid over the trunks and are woven together with a Chitimacha basket pattern. Louisiana maps merge with Oklahoma maps as the two weaving styles collide. My son, Archie, is discretely woven into some of the pieces as he stands in the Broken Bow landscape and is then woven into Tahoe, reflecting on connection after relocation. Maps and archives from the past woven into contemporary landscape photography close a gap of time. Similarly, placing a figure into a landscape can also blend time and represent Indigenous futurism by reclaiming space and re-implementing self into a land of ancestry that was otherwise taken from the ancestors. This process of weaving together past, present, and future broadens the visual experience to something that is felt and not seen, bringing spirituality into the works. – Sarah Sense (Chitimacha / Choctaw)

Sarah Sense (b. 1980) lives and works in California. Sense has traveled extensively through the Americas, Europe, United Kingdom and Southeast Asia. Her landscape photography is an essential part of her travel and visual art practice. Sense’s weaving practice began in New York while a master’s student at Parson New School for Design (2003-2005). While director and curator of the American Indian Community House Gallery, New York, Sense catalogued the gallery’s thirty-year history, inspiring her search for Indigenous art internationally. Her world travels were charged with archive research, photo-weaving project that expanded to community programming, international Indigenous artist interviews and the book, Weaving the Americas, A Search for Indigenous Art in the Western Hemisphere.

Instagram: @sarahjewellsense

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 2 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) collection of the Choctaw Nation

Living and traveling through four continents for a decade, has privileged me the opportunity of learning about contemporary Indigenous life and settler-colonial histories. With my landscape photography and familial weaving traditions, I re-envision basket patterning from my Chitimacha and Choctaw heritage by weaving photographs of maps, manuscripts and landscapes to tell stories of colonialism, resistance, and resilience. The act of cutting and weaving together old maps and new landscapes with traditional patterning, re-indigenizes the landscapes while decolonizing maps.

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 3 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) collection of the Choctaw Nation

Can you talk a little bit about your background and what inspires you?

I am an artist from California who works with family history and archives to create woven photographic mats. My inspiration is traditional Chitimacha and Choctaw baskets coupled with my family history of weaving. The images in my work include family archives, maps, documents and landscapes that explore colonial histories, settler impacts, family trauma, and institutionalized racism. My parents moved to Los Angeles as children, but each grandparent is from a different place: my maternal grandfather is Chitimacha from Louisiana and my maternal grandmother in Choctaw from Oklahoma. They met in New Orleans, Louisiana before moving for my grandfather’s work. My paternal grandfather is from Kiel, Germany and immigrated to New York from Hamburg just before World War II. My paternal grandmother’s distant ancestry goes back to England and Norway, but she grew up in Texas before moving for my grandfather’s work. I have spent decades researching the family history of all four grandparents. From these research projects, imagery has emerged that I work with in my photo-weaving practice. My archive research varies, but my most intimate archive experiences are with the Chitimacha and Choctaw baskets. I view and hold the baskets in museums whenever possible. I am very humbled and grateful to connect to my ancestors in this way.

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 4 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) collection of the Choctaw Nation

What type of techniques аre involved in your projects? Talk a little bit about blending contemporary photography with the traditional basket weaving techniques of your Chitimacha and Choctaw ancestors?

Weaving photography is my form of storytelling. When placing imagery together, I am aesthetically color blending and conceptually developing stories and political statements. While working with color and image to find the beauty in landscapes and archival documents, the themes can be traumatic. Without using obvious violent imagery, I try to work with a pallet that is soothing and inviting. I want the colors to be calm and gently magnify the beauty of the ancestral patterns that I am weaving. I like to step back from a piece and enjoys the patterning and weaving technique as it blends the colors like a painting; and then come close to the piece to see the map locations, text, landscapes and figures. Then the story unfolds. Usually, the viewer will need some additional text to understand the map and image locations, so I do rely on my writing to explain the content in the work. I hope that the beauty intrigues the viewer to look closely and that the close encounter encourages reading. Then the piece can really come to life for a viewer and be educational.

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 5 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) private collection

How do specific places and moments in time help to shape the perspective in your work?

Time is a relevant part of my work. Maps and archives from the past woven into contemporary landscape photography closes a gap of time. Similarly, placing a figure into a landscape can also blend time and represent Indigenous futurism, by reclaiming space and re-implementing self into a land of ancestry that was otherwise taken from the ancestors. This process of weaving together past, present and future, broadens the visual experience to something that is felt and not seen, bringing spirituality into the works.

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 6 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) private collection

How does art and activism come together in your work to address issues like environmentalism and colonization?

In the past couple of years, I have been working with trees and roots in my work while thinking about the communication of natural, organic things in our environment. Through meditation and stillness in nature, I find connectivity and gain knowledge. I am always looking for ways to connect to the natural environment. As a mother, my bond to my children is the most important part of my life. My three boys reply on me for everything and it is my responsibility to meet all of their need so that they can thrive. Extending that relationship with nature, broadens a bond of love. Showing that love of environment to my boys and sharing a bond with each other and nature is nurturing and grounding. Any environmental issues addressed in my work starts with these bonds. It is the love and care for humans, animals, and environments that encourages any political elements in my work. The colonial maps are historical evidence of wars and genocide. The landscapes are acknowledgement of the beauty that is in nature, a reminder that a colonial map is more that territorial lines, it is a documentation of a natural environment and a home to Indigenous people.

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 7 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) private collection

How can the art community as a whole, continue to elevate Indigenous voices, and support Indigenous artists today?

Native artists and art taking space in institution gives Native people a voice in an otherwise compromising colonial space. Art is a beautiful way to educate. Inclusion of Native voices in these spaces is essential to understanding the history and impact of ongoing colonization as well as the presence of Indigenous people today. Bringing Native art and voices into these spaces helps the larger effort of guaranteeing a future for Indigenous people.

©Sarah Sense,Hinushi 8 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 40″ x 80″ (45″ x 85″ framed) private collection

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 16 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 46″ x 46″ (50″ x 50″ framed)

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 17 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 46″ x 46″ (50″ x 50″ framed)

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 18 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 46″ x 46″ (50″ x 50″ framed)

©Sarah Sense, Hinushi 19 2023 archival inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle bamboo paper and Hahnemuhle rice paper, wax, tape 46″ x 46″ (50″ x 50″ framed)

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025