Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis

Front cover of Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024); cover image: Kelli Connell, Doorway II, 2015. © 2024 Kelli Connell

Pictures for Charis is the culmination of Kelli Connell’s quest to bring to light the writer, Charis Wilson, partner, muse and creative collaborator of Edward Weston. In a combination of images and text, the book braids reverie and road trip, leading us on a photographic pilgrimage. Connell travels with her partner Betsy Odom, making photographs in the same locations as Weston and Wilson did 80 years ago. Through Edward’s photographs and Charis’ writings, Connell finds affinities in the physical and emotional landscapes she and Betsy now traverse.

There is a tenderness in the way Connell photographs Betsy, observing and honoring her interiority. The cover introduces us to Betsy in an inwardly folded pose, recalling Weston’s iconic image of Charis. Suites of Connell’s revelatory photographs punctuate the pink text pages of reflection and research. She studies Edward and Charis through their creative lives, navigating the terrain of her own relationship as she begins to understand theirs. As her observations grow more nuanced, the eloquence of the landscape emerges and merges with photographs of Betsy. A lavender bookmark reminds us of Connell and Odom’s place in the present.

Pictures for Charis is co-published by Aperture and the Center for Creative Photography, Tuscon and will be exhibited at the Center for Creative Photography, High Museum of Art, Atlanta and the Cleveland Art Museum.

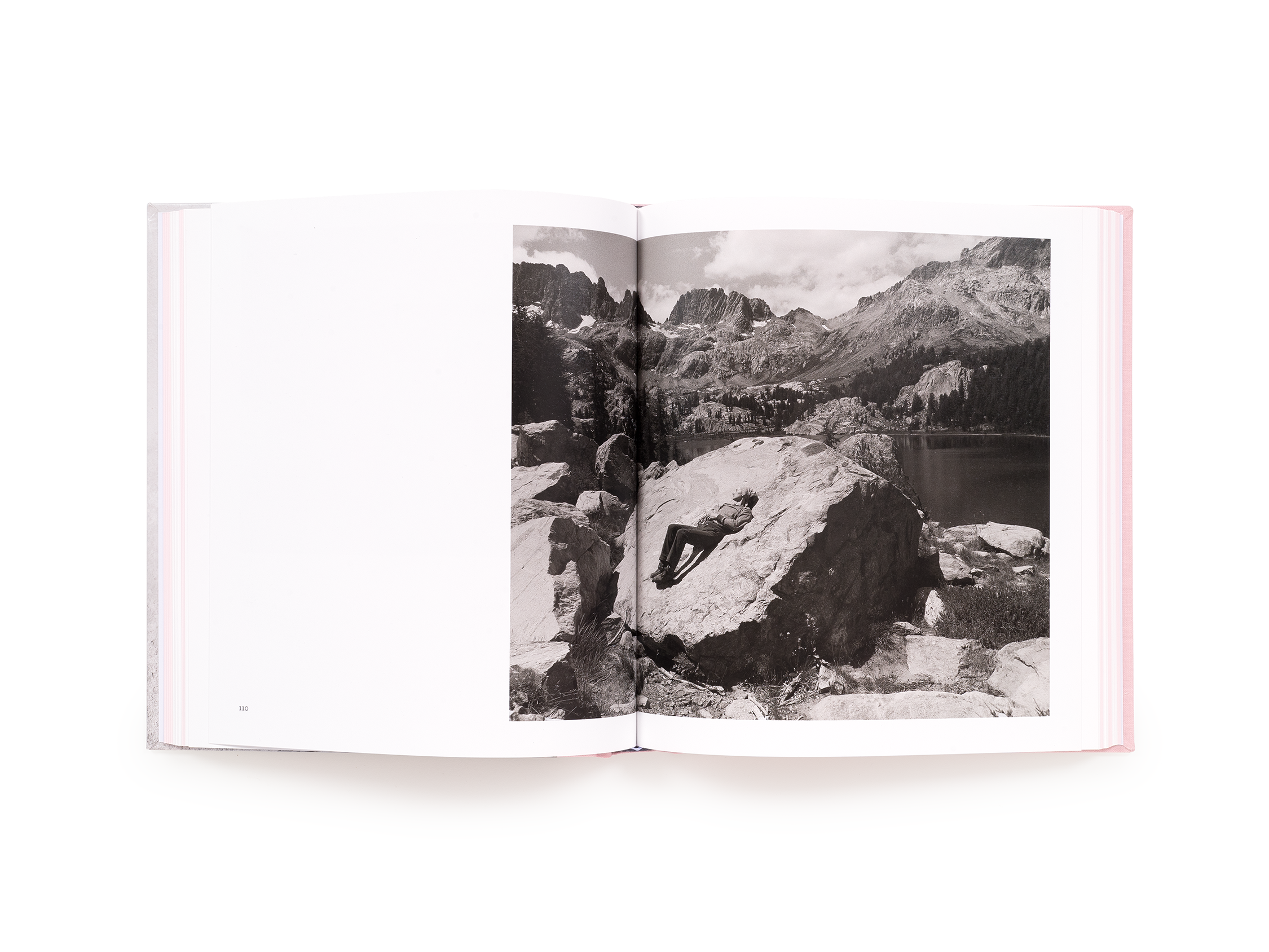

Kelli Connell, April, 2008; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

Book spread from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024); cover image: Kelli Connell, Doorway II, 2015. © 2024 Kelli Connell

BC: I was startled by the first photo of Betsy in the book, where she meets our gaze so openly, and by your diary-like text that invites us into your personal life. It struck me as such a contrast to the ambiguities in your long-term project Double Life. How is Pictures for Charis a departure from or an expansion of your interest in picturing relationships?

KC: In Double Life, we see what appears to be two women in a relationship. The scenes are often domestic, with the same model, Kiba Jacobson, taking on both roles of the portrayed characters. In this work, the two characters are enthralled with one another, yet never meet our gaze. This approach allows the audience to consider moments of life captured, as outsiders, not unlike how we analyze film-stills from a movie. In this work, I played a stand-in and spent much of my time in front of the camera acting out each scene with Kiba.

In Pictures for Charis, I stayed behind the camera as I photographed Betsy. These portraits are not composites and Betsy meets my gaze. In turn, she confronts the audience directly. Instead of being one step removed from the relationship we are witnessing in Double Life, Pictures for Charis provides an intimate view of someone in a relationship, as she gazes upon her partner through the camera’s lens.

My work has always been personal. I utilize my own experiences in regards to my sexuality and relationships. Both projects address these concerns, and yet, Pictures for Charis strips off a layer, allowing the audience into my own private life, if only for a few encounters. It seems that the older I get, the more willing I am to share a more raw and vulnerable side of myself through the work I make.

Pictures for Charis also speaks to Charis Wilson’s experience as a model for Edward Weston and how the interpretation of this work has shifted through history’s ever-changing lens. I am fascinated by how our own understanding of the relationships we are in shifts over time.

Kelli Connell, Preston, 2013; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

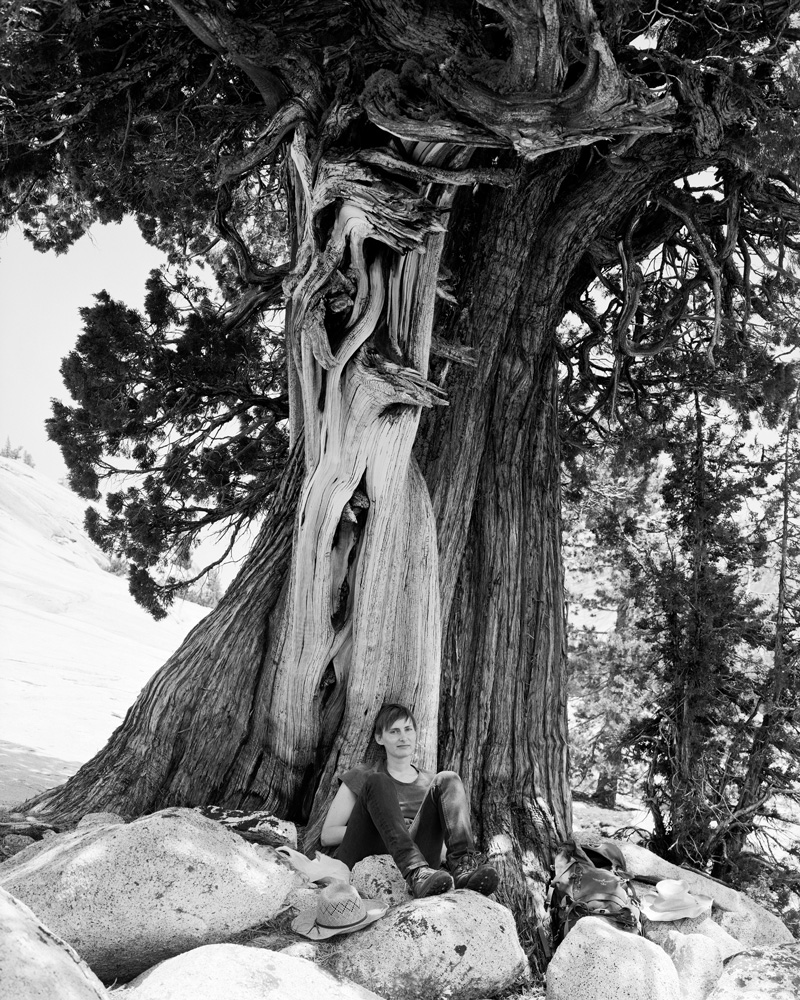

Kelli Connell, Betsy with Junipers, 2016; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

BC: I loved seeing the evolution of your vision to embrace landscape. Can you speak about how that unfolded for you over the course of your project?

KC: The landscape photographs in Pictures for Charis serve as an homage to Charis Wilson. Her descriptions of places in California and the West (1940) are evocative – full of atmosphere and with great detail about the landscape, as she and Edward traveled out west. I wanted to experience the places I had learned about through Charis’s writing and wondered if I could feel what it might have been like for her to be in these places. I was curious to know how this pilgrimage might be different for me and Betsy, as a queer couple, retracing their footsteps eighty years later. In chasing Charis’s ghost, I was following the supporting character of a narrative, not the main character in the story as it relates to Edward’s life. Trying to get closer to her was a thrilling and elusive journey.

Weston was a detail-oriented, perfectionist when it came to his photography. For me, I was interested in discovering what not only he had photographed, but what was in the peripheral – to the left, right, or behind the camera. I was also intrigued by the echoes and emotion created through juxtaposing landscapes, portraits, and adjacent text in Pictures for Charis. The landscapes, as sequenced in the book, evoke humor, grief, loss, hope and change.

Kelli Connell, Betsy, Dandelion, 2015; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

BC: Weston was adamant about not reading into his photographs and Wilson felt his work was misunderstood. How do you want us to ‘read’ your landscapes?

KC: The landscapes in Pictures for Charis provide an emotional pacing as these views are interrupted by portraits of Betsy, often made in the same locales. Embarking on a pilgrimage to a place allows us to perhaps get closer to someone, at least by experiencing things that they had once experienced. The landscapes, for me, function as records of this shared experience, a bridge between the decades, of the relationship of Charis and Edward and me and Betsy. They also speak to my perspective as a woman making photographs through a feminist and queer lens.

Kelli Connell, Point Lobos Flowers, 2015; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

Kelli Connell, Betsy, Lakeside, 2009; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

BC: You write that you initially disliked Weston and had “instinctually lashed out because I had learned about him [Weston] through the filter of all the cultural and artistic biases of our times.” What did you come to appreciate about him through Charis’ writing? And did your view of Charis change as you retraced their journeys?

KC: I learned that Weston became distilled, reduced, and mythologized through the telling and re-telling of history. Often, what we understand about someone depends on who is telling the story, and these storytellers often use information to support their own agendas or values. Charis helped me to see that Edward was a complicated individual. He gravitated towards a life that was against societal expectations and norms. Many of the people he was close friends with were artists who lived their lives against the grain – mystics, poets, independent women, and bohemian spirits who were free in their sexuality and dedicated to living a life that supported their creative pursuits.

I believe this was radical back then and Charis helped me to remember that we will never really know someone after they have left us. We will all become reduced to the stories that other people tell about us when we are no longer here. Charis’s voice, through her writing, also provides insight into who she was — as a strong, charismatic, quick-witted, and intelligent women. She not only shares her experience of their eleven-year relationship as it moves from desire to companionship to struggle to pain, but we are also given a deep understanding of who she was as a person, and this helps us to see the pictures Edward made of Charis through her lens.

Kelli Connell, Chama River, 2018; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

Kelli Connell, Betsy, Santa Fe, 2016; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

BC: In 80 years when your work is revisited, what do you hope is seen in and understood about the current cultural and artistic moment?

KC: I would hope that this work would speak to the importance of reconsidering history and trying to understand it through multiple viewpoints and first-hand accounts, when possible. I am interested in the stories that are not told, or recorded, as well as stories told by people who are not of the majority with heteronormative values. My work will be reinterpreted as time moves on, even by myself, as our own understanding of things continually changes. More than anything, I would hope this work speaks to our shared need as humans to connect and understand one another, as well as to discover, uncover and champion histories by women, BIPOC, LQBTQ+, and other marginalized people.

Kelli Connell, Surf, Point Lobos, 2015; from Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (Aperture, 2024). © 2024 Kelli Connell

Details

Aperture

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 280

Number of images: 109

Publication date: 2024-03-19

Measurements: 9.1 x 7.85 inches

ISBN: 9781597115599

Instagram: @aperturefnd/

Kelli Connell (born in Oklahoma City, 1974) is an artist whose work investigates sexuality, gender, identity, and photographer/sitter relationships. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts Houston, among others. Connell has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, MacDowell, PLAYA, Peaked Hill Trust, LATITUDE, Light Work, and the Center for Creative Photography. Connell is an editor at Skylark Editions and a professor at Columbia College Chicago.

Instagram: @kelli_connell/

Betsy Odom is an artist, curator, and educator based in Chicago. They received an MFA from Yale University School of Art and a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. They are the recipient of numerous grants and awards including a DCASE Grant, Illinois Arts Council Artist Grant, and a West collection acquisition prize. Odom’s work has been reviewed in publications including Artforum, Fabrik magazine, and the Chicago Tribune.

Instagram: @betsyodom1/

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026