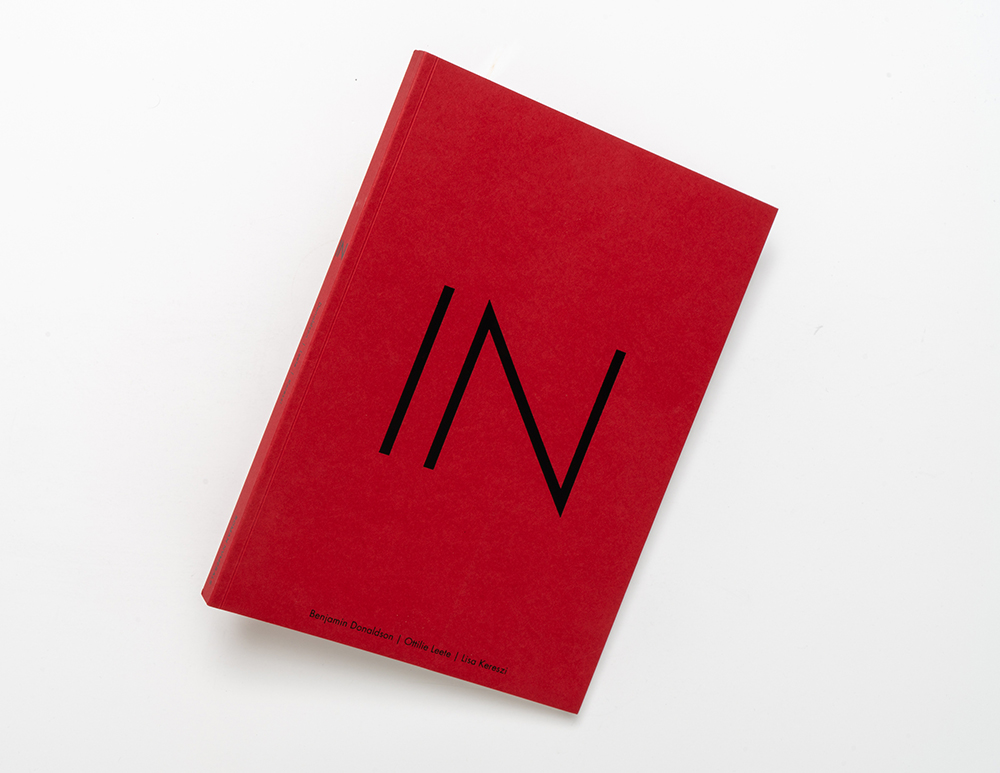

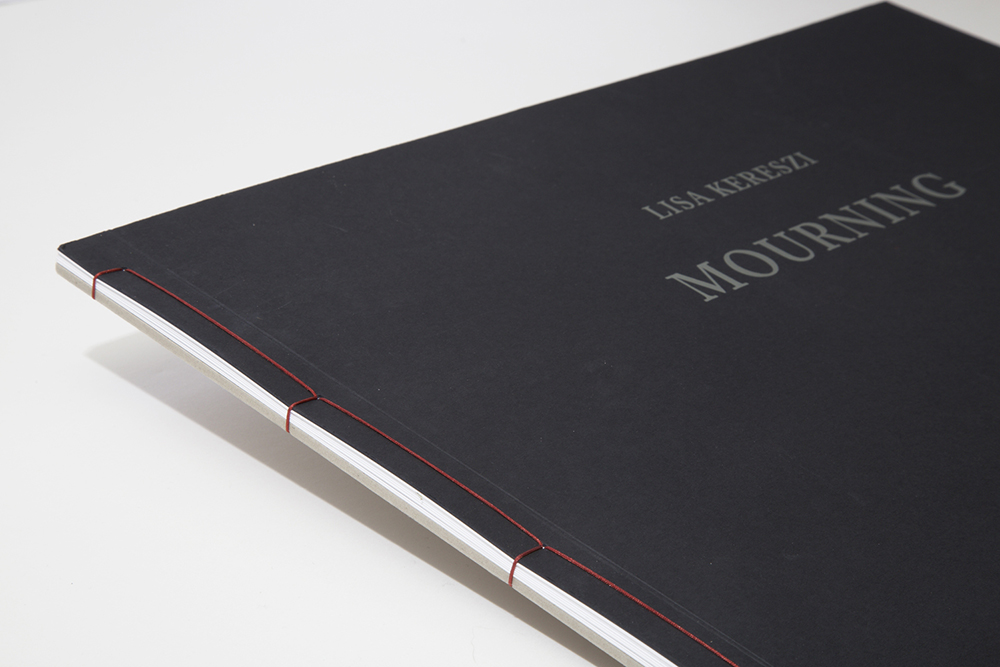

Lisa Kereszi: Mourning and In

In the realm of contemporary photography and photobooks, Lisa Kereszi stands out for her deeply personal and evocative works. In this feature, we delve into two of her newest projects: MOURNING and IN. MOURNING is a poignant exploration of grief, born from the sudden losses of her father and grandmother. Utilizing a trail camera to document visits to her father’s grave, Kereszi captures a unique narrative of remote mourning and memory preservation, transforming surveillance images into a tribute. In contrast, IN is a collaborative family project created during the pandemic, blending photographs from Kereszi, her husband Benjamin Donaldson, and their child, Ottilie. This experimental book encapsulates the shared experience of lockdown, merging perspectives to depict the magic and monotony of confinement. Through these distinct yet intertwined works, Kereszi’s art navigates the complexities of loss, memory, and familial bonds. I know Lisa from the Hartford Art School’s MFA program where I was a grad student and she was our resident critic. I always appreciated her grounded view of both photography and life and I am happy to continue our conversation.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Lisa Kereszi and Tracy L Chandler.

TLC: Can you tell us how the MOURNING pictures came about? Did you always intend for them to be a photobook project?

LK: There are two ways to approach this question. One is talking about the final product, which is the book, and another is discussing the making of the pictures. Both the work and the book started as part of a bigger ongoing project I have called “Sunrise, Sunset,” which is about loss, and holding onto physical belongings from previous generations, and about inheriting their emotional and psychological baggage along with their dna.

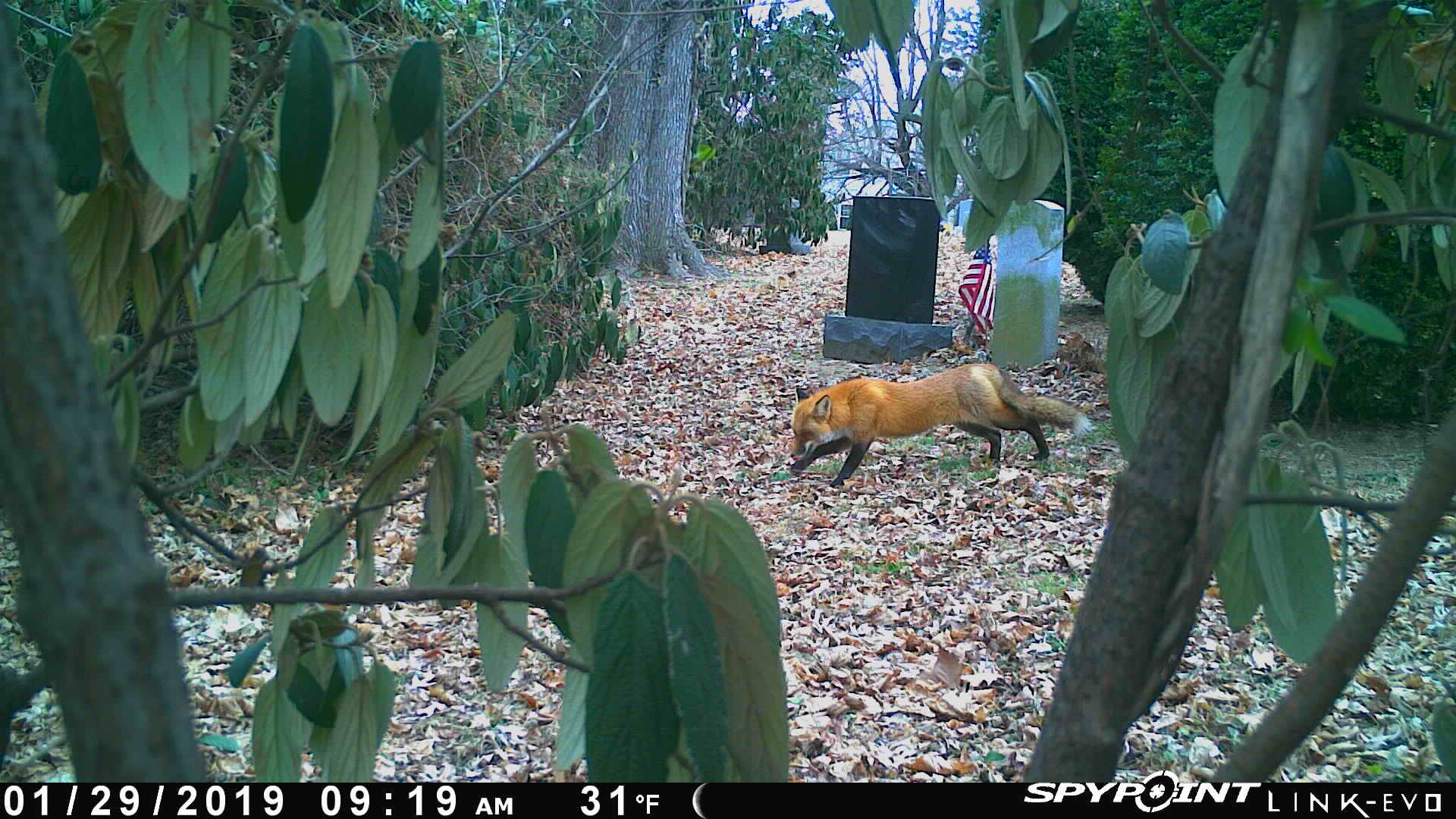

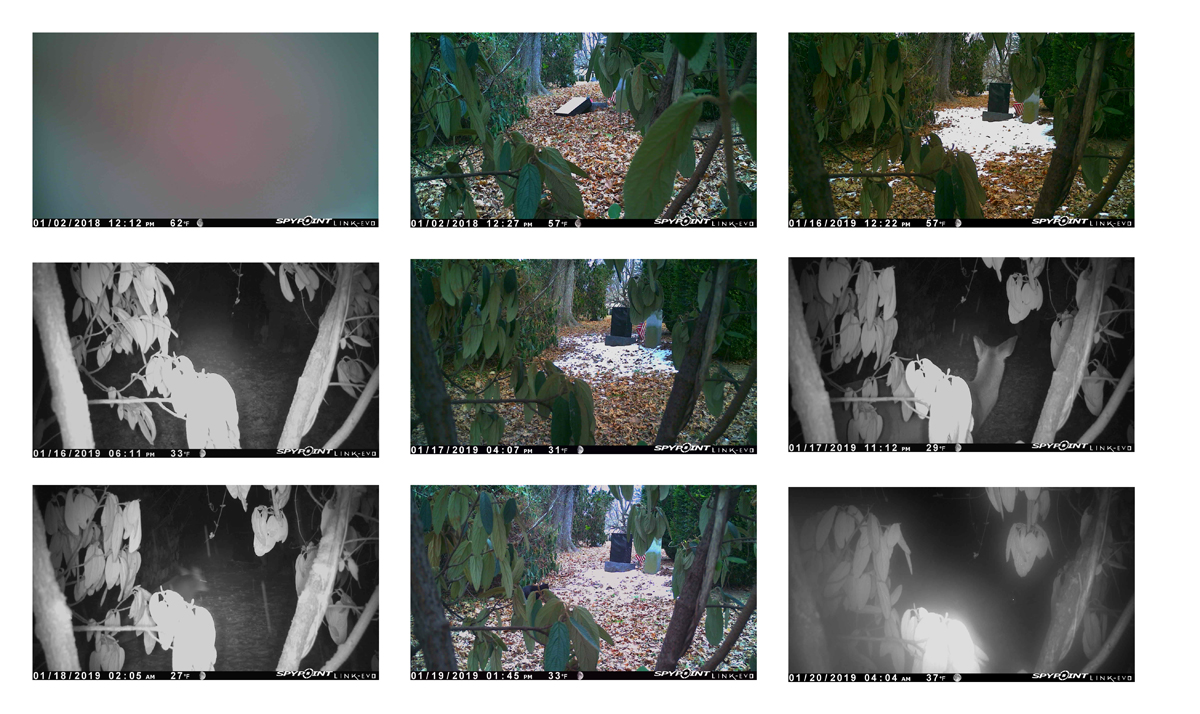

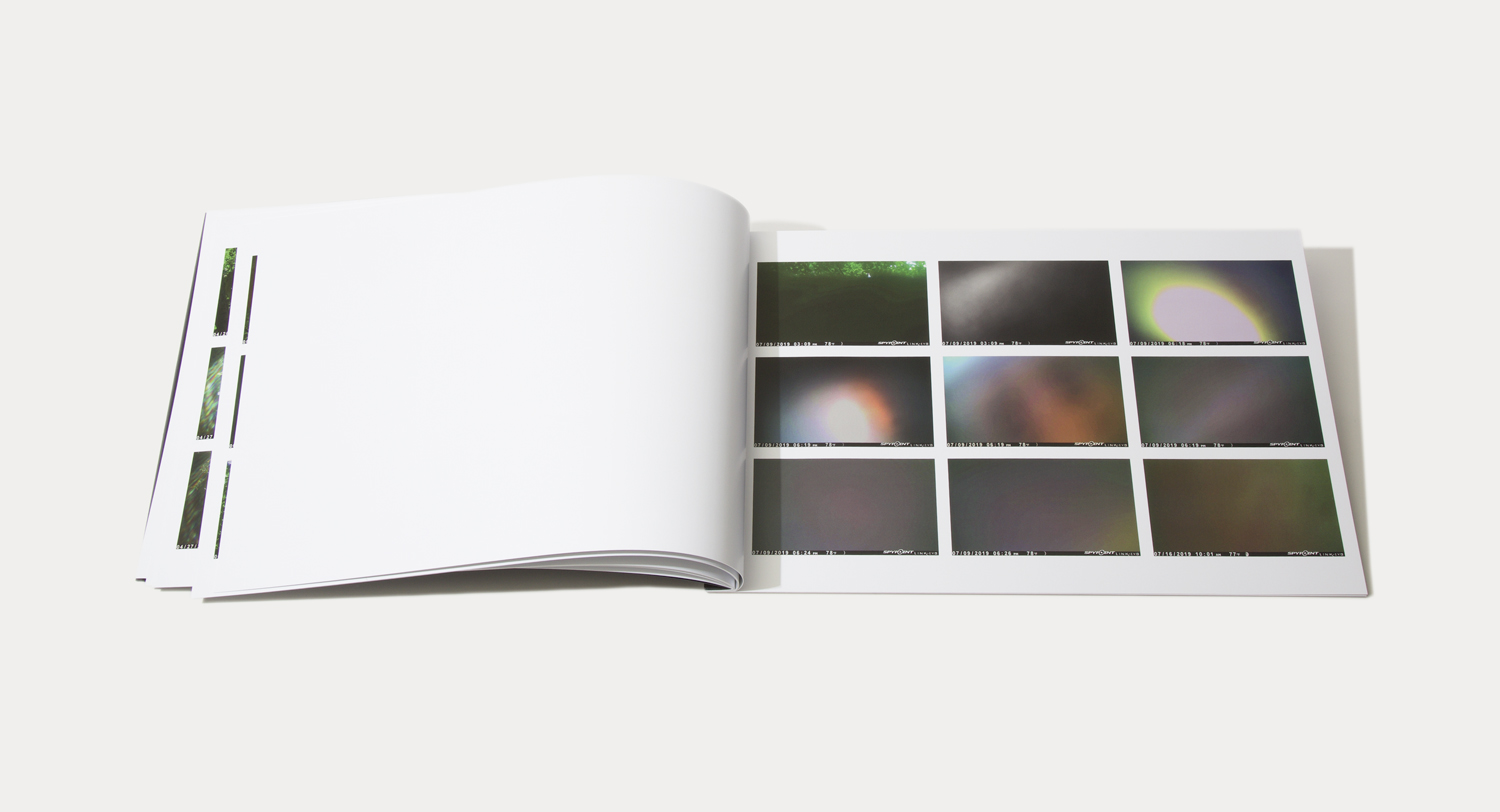

My grandmother and father both died in very quick succession in 2017-18, which led to a mess of family drama, and during that period I became obsessed with the stuff that they left behind, trying to hold on to the remnants, in order to keep some sense of control. In the midst of all that, and shortly after my dad’s grave stone was erected, it was toppled. Was it a disgruntled family member? A group of rowdy teenagers? I decided to install a trail camera as a way to keep an eye on things. I would check the files every morning and evening. It became routine – a ritual. Initially, my goal was to monitor for any vandalism, but over time, and as the offense was not repeated, the focus shifted to the array of images collected by the camera. Despite my concerns, the camera captured fewer human visitors than anticipated. Objects like flags and flower baskets appeared, suggesting visits, but the camera’s positioning among the trees and the motion sensor’s limitations meant I rarely saw the visitors themselves. Other than the grave, leaves, light and landscape, the main moving subjects became the landscapers, my mother adjusting the camera, and the local wildlife.

But yes, of course I did always think that I would use the pictures one day – but only as part of that bigger thing I am making about losing these people and carrying on with life. In Spring 2022 during a Zoom meeting with publisher and longtime collaborator and friend, Michelle Dunn Marsh from Minor Matters, I was showing her a larger book idea, but she immediately responded to the trail cam pictures, and suggested pulling them out to form their own thing. She asked me if I ever thought about making them into an artist book. Following her suggestion, I immediately focused on organizing the trail cam pictures, taping and pasting printouts together to work through compositions and figure out what worked best.

TLC: This trail cam is a very specific kind of camera. Were there any technical issues or surprises as you worked with this technology?

LK: At some point in the summer, the branch holding the camera fell due to a storm, breaking and altering the camera’s aim to point upwards towards the sky. When I saw the images, I thought. ‘Oh my God, it’s like heaven. The body is laid out. The soul is ascending to heaven!’ I interpreted it as a poignant metaphor for death and ascension, transforming the malfunction into a powerful part of the narrative. The camera, originally intended for surveillance and protection, inadvertently recorded a light manifestation as a metaphor for death and dying – the light at the end of the tunnel.

TLC: You are doing two things here. One, as a daughter, you are keeping a sort of death vigil, almost like a period of mourning, remotely visiting this grave daily. And the other, as an artist and photographer, you are working with form and light, engaging the world via the camera. Did you find making this work therapeutic?

LK: Yes. If you look at my work, so much of it is about family. And even the stuff that’s not about family is about family. At my final crit in graduate school, Gregory Crewdson said “Your work doesn’t have to be of your family for it to be about your family.” I was going out and photographing all these strip clubs and nightclubs and escapist kinds of places. It’s like he was saying, “It’s still about your dad. It’s about your family. It’s about trying to escape the reality that you were born into.” I couldn’t have verbalized that at that time. So much of my childhood was about shame and about trying to escape what my identity was or what I thought other people’s ideas were about white trash, outlaw bikers, addicts, and junkyard people. And the irony is that so much of my work is about him, the guy that wasn’t home for dinner and his plate would get cold waiting for him, and not about my mother, who held it all together, held us together. She even was instrumental in this work getting made, maintaining and troubleshooting the camera. So, yes, I think for me, making artwork is therapeutic, but it’s not like quote-unquote art therapy. It’s that so many of us do this because we can’t do anything else, and we need to survive. To make sense of the senselessness. Making art is necessary to live for most of us. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

TLC: I am thinking of the word remnant and what is left behind. What is your experience of photography’s interaction with remembering and to holding on to what/who was, especially in the context of mourning and loss? It is interesting that you have one of your photographs engraved into your father’s headstone.

LK: It is so much about all of that. That is one of the things photography is so good at, because it is indexical; it is a record, and it is fixed and immutable – well, except for the ravages of time, heat, moisture, bad storage, fire, etc. I always marvel at a Daguerreotype and how we can hold in our hands a bit of the true cross in that little case – something that was in the room with the sitter: be it Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, or your ancestor, which recorded the energy that bounced off of them and onto the plate. The tombstone with the portrait is important because it is everlasting – or at least longer than the c-print or color neg the picture lives in in its original form. And photography has been so much about memory for me, anyway, whether it’s because I honestly have a terrible memory for things that have happened, especially in childhood, maybe my brain’s way of protecting itself, or also because of my early exposure to the idea that photography can aid in memory – by my early exposure to Nan Goldin’s work, when I was a fan in college, and then her assistant in the late 90’s.

TLC: Whoa! You were Nan Goldin’s assistant?! Tell me more about how that experience influenced your idea of photography aiding memory. Were you working with her when she was making the Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing work?

LK: That work preceded me. I vividly remember being in college at Bard in my dorm room junior year and looking at the “Ballad,” and proclaiming to my then-boyfriend that I wanted to move to New York after graduating and be her assistant. And then a few years later, in 1997-98, I was. That was during the lead-up to, and including the Whitney retrospective, “I’ll Be Your Mirror.” It was a wild time, when she broke a bit more into the mainstream art world. So although that was well after the “Witnesses” work was made, I was involved in collating and copying and organizing some of that work along with everything else. I saw firsthand how photography could be this obsessive action one needed to take to hold someone close, her sister, then others, as the members of her chosen “Family of Nan” all started slipping away. She also kept obsessive diaries in these little red books. I hoped they would go to an archive someday, with restrictions for a hundred years or her lifetime or whatever, but I think I recently read somewhere that they will be destroyed. The keeper, preserver, and hoarder in me hates thinking about that, although I guess I understand. It is my connection to her work that was one of the reasons I approached Marvin Heiferman to write for the book – that and his gridded memorial project via Instagram, whywelook, which is also a mourning diary.

TLC: Like Nan and Marvin, your work blurs the line between public and private mourning. How is your experience of sharing such a private experience with a wider audience?

LK: I think it is part of mourning in Western culture, or at least it certainly was in the 19th century, that you put on your black clothes and you go out and you let everybody see that you’re sad. That was part of it – mourning as performance in order to have a framework to get through it. It’s an interesting experience putting this book out in the world. The other night at an event, people were coming up to have me sign the book, and they’re holding this thing in their arms close to their body that contains a sequence of otherwise private images of my family’s grave. It’s weird to think about, and I have to dissociate a little bit.

TLC: How do you see the role of technology evolving in the way we mourn and remember the dead, particularly through photography? Think of how many emails, texts, images and videos we have on our cell phones!

LK: Yes, and it is both comforting that someone can go in and see what my day-to-day life was actually like (a descendant, a researcher), but also terrifying that it is not exactly physical, these bytes and bits, and that it would have to be saved on purpose and backed-up, or else – poof! When Marvin was working on the piece for the book, he was fascinated by all of this tech related to mourning and sent me a few articles on the ways in which it has appeared in cemeteries to aid and comfort the mourner and to try to keep some version of someone alive. I guess photography was just one step in this journey to hold onto things forever, and maybe AI or whatever else is just the latest tool.

TLC: Exactly. The irony is that the amount of imagery is growing exponentially yet the technology evolves so fast now. It becomes obsolete. I definitely don’t have a CD rom drive to view my photos from the early 2000s. But you are bringing things full circle. You are taking this originally digital work and bringing it into IRL as a physical book. Is this an object to replace the personal items your family lost?

LK: Yes, I think it is important to remember that photographs are prints – we talk about that at Yale all the time, the photograph as “object.” Maybe it’s such a hot topic now, because most photographs that exist in the world today are mere images, those bytes and bits, on a screen and in the ether. But we only know what someone looked like or what the world might have actually looked like because prints and negatives from the past still exist. The indexical nature of the medium is important, and the preservation of that index is equally crucial. My advice: Back it up and print it out! But to answer your question – no, I wouldn’t have thought that it replaces the stuff I couldn’t get my hands on that was lost and scattered to the wind, but it’s interesting to think about. I definitely saw the picture-making and then the grid assembly as a means to feel more in control, even if it wasn’t conscious at the time, it became pretty clear as the book was assembled in my work with Michelle that that is what I was doing. But yeah, I guess it is a family album. Ironically, though there are a handful of family photos that it sickens me to think that either they are lost or hidden somewhere with another family member, I actually have a lot of material. I have dozens of my grandmother’s notebook diaries, which are the basis of “Sunrise, Sunset,” as well as my dad’s albums full of pictures of classic cars, Harleys and biker babes, which I used to create The More I Learn About Women, (2014, J&L Books.). It’s also not lost on me that MOURNING is essentially the same scale as my grandfather’s scrapbooks that I pulled pictures and pages from for Joe’s Junk Yard (2012, Damiani.) In the 80’s he tore up the family albums and cut up newspapers and magazines and scotch-taped them in oddball juxtapositions on those big, grocery-store craft-aisle, construction-paper pads kids use. I am the keeper of the family archive. When I shared some of that material in the photographic scholar Laura Wexler’s photo history class years ago in conjunction with the junkyard work, she encouraged me to consider donating the scrapbooks to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale, saying, why shouldn’t they have represented among the archive (with Steiglitz and O’Keefe, and too many poets, writers, artists to list) a first-generation WWII veteran, former boxer-turned-junkman? I can’t really argue with that.

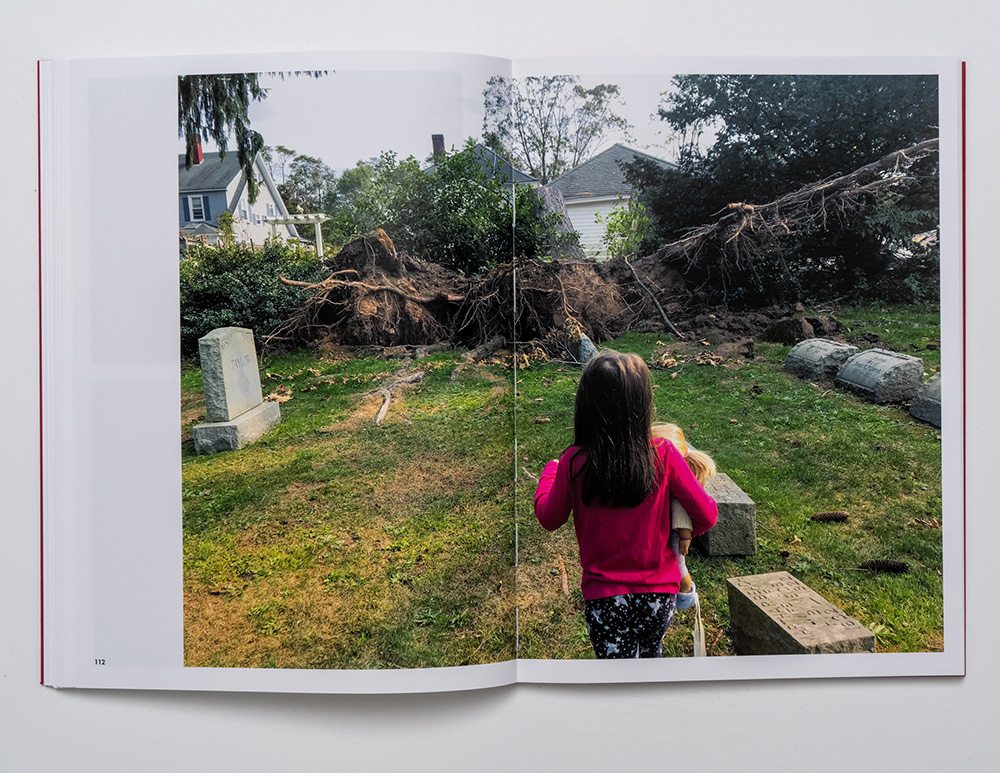

TLC: That’s a good point! And you are the family keeper. And continue to be for the next generation. I’d love to pivot to IN. Another exploration on the theme of family but in a much different way. You made this work during the pandemic with your husband and daughter. The book blurs the lines of individual authorship. It makes me think of how time all kind of melded together during that period. People too. It all became smeary. How did each of you contribute to the creation of the book, and how did you decide to blend these contributions seamlessly? Did you ever consider delineating who made what?

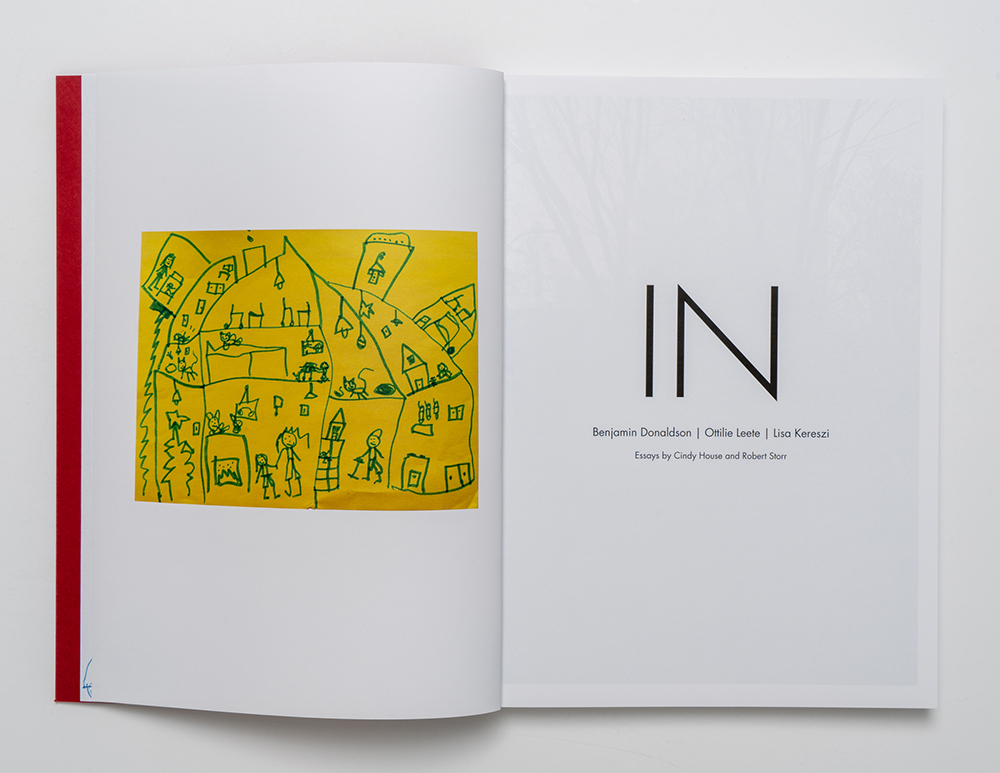

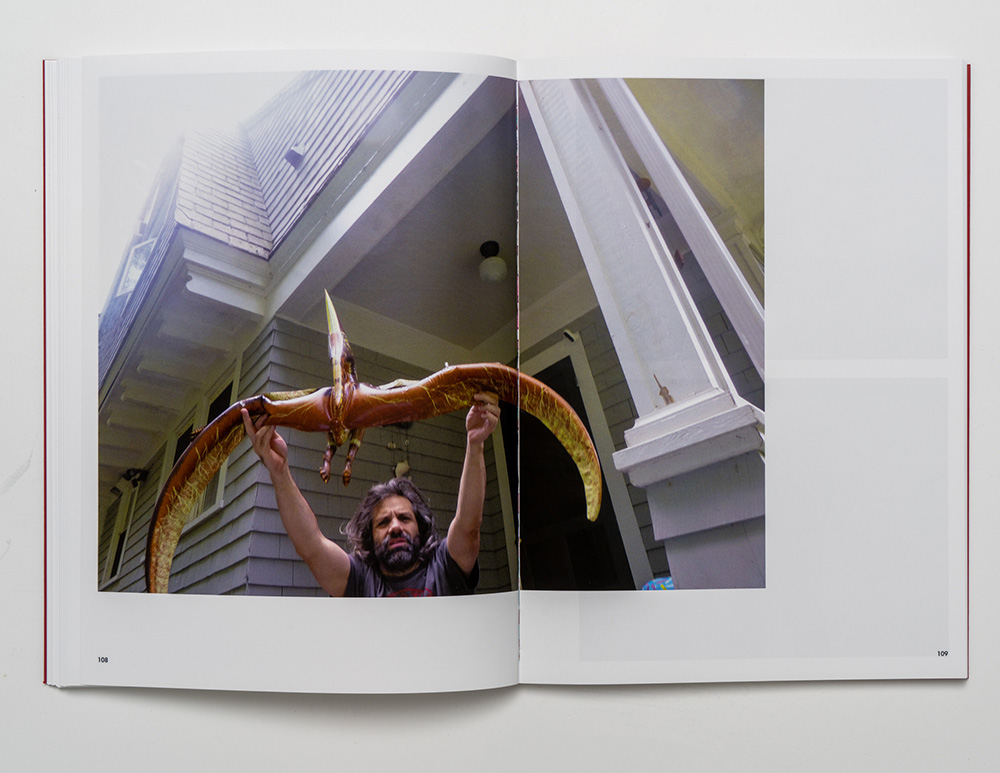

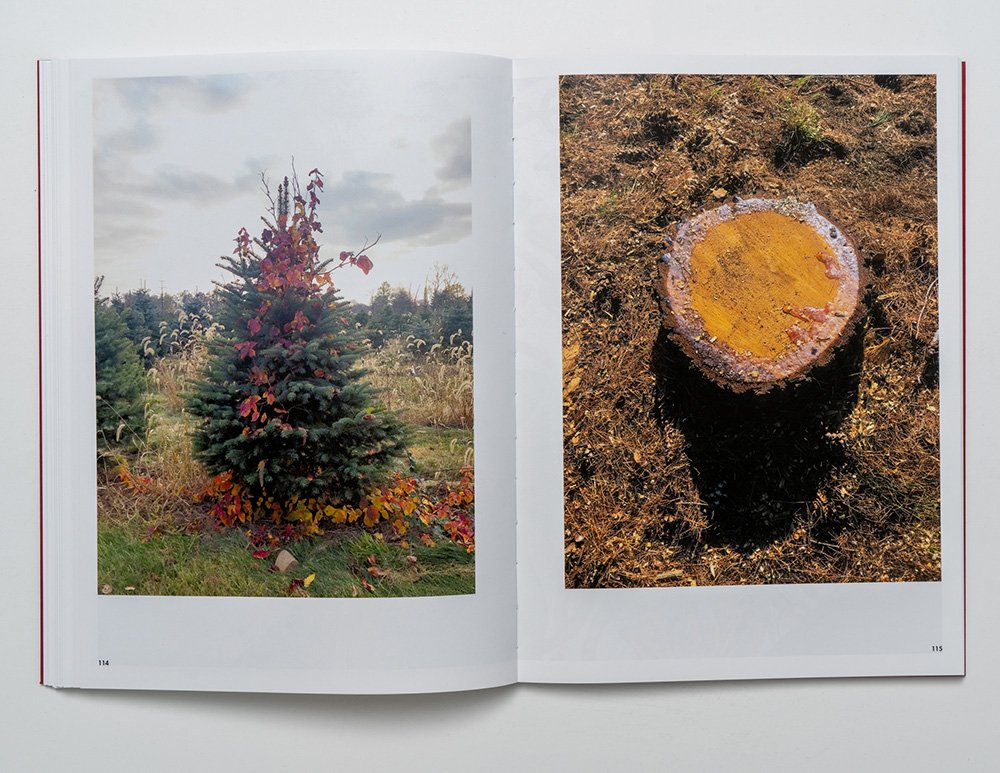

LK: Yes, so I find it sort of ironic that I am a photographer who is actually pretty formal and conventional in composition, but have a solid published record now of using collaboration via appropriation – a bit with Joe’s Junk Yard and The More I Learn About Women, too, using photos by family members. In MOURNING I did not set up the camera – actually my sister did, and in IN, I only took ⅓ of the pictures. It made total sense for us to collaborate on IN as a family, although honestly we did create 3 separate volumes at first – 3 edits of each of our work that would be slipcased together in a three-volume set. We liked the idea of threes, and toyed with titles like Trio, Triangle, Triumvirate, even, until the brilliant designer Yve Ludwig, singled out the word “in” from one of Ben’s photographs of me with a flash card taped to my forehead. And speaking of collaborators, it was publisher Michael Vahrenwald who could not get behind the idea of marrying three separate volumes with a slipcase. He always suspected there was something better here in the “smeary” (to use your brilliant word) and messier, but somehow harmonious mixtape of what IN became in his capable, editor hands. He is really the one who gave the book shape by taking our three independent sequences and (mostly) using Ben’s as the intro and base, then weaving in my and our daughter’s pictures along the way, as they slowly took root and gained momentum in the edit.

I, myself, sometimes now get confused as to who took what, which speaks to the success of the mash-up. The only way to find out is the Highlights Magazine-like key in the back, which is in a tiny font, and upside down at the bottom of one of the last pages. I had suggested color-coding the page numbers in primary colors, but no one else thought that was a good idea. It is currently so understated and hidden that I think many readers don’t even see it, which I love.

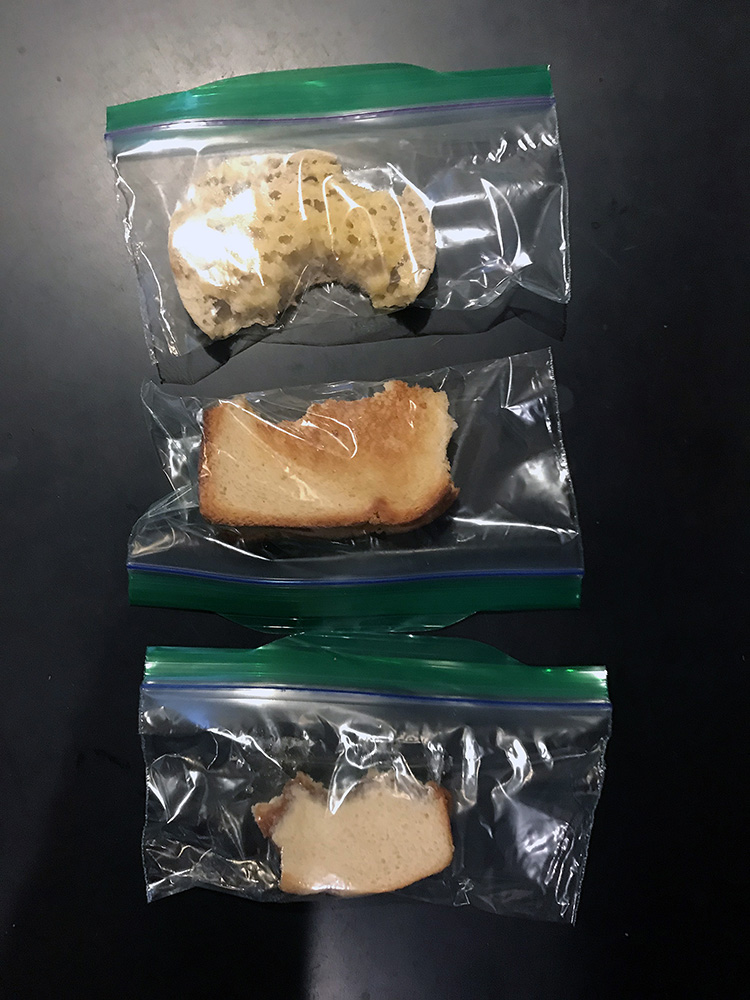

TLC: Yes! I love that. Viewing this book is a bit of a game at first but then we stop caring about who made what and we embrace the blended experiences. IN seems to embrace the confinement and the need to hang on to life and living during a strange and scary time. Was photographing together a way to stay sane? How do you think the inclusion of photographs from your child’s perspective influences the viewer’s understanding of the lockdown experience?

LK: Yes, I do like that game aspect, too, especially since one of the authors is more into games than photo books! Since photography is a part of our lives, yes, it definitely helped. And shooting together as well as separately as individuals helped with the boredom. We normally do play with dress-up like masks and experiments like dry ice or go for walks and beachcomb, but there was a heightened sense of reality and performativity when the camera was picked up, and especially when the flash got plugged in. And it was a no-brainer that a child’s perspective was a huge part of the book – parents and child. So much of the drama in the world and in the news and at school board meetings was all about kids – about whether or not they were virus vectors, or should be wearing masks, or should be home or in school with plexiglas dividers, and whether they were at less risk of complications or not so much, and what of homeschooling and what of Zoom School, and what to call this generation? All this talk about them and above them must have been very disempowering, especially for the ones who could understand. Thank god she wasn’t older, I think, because it must have been even harder to be a teenager with all the socializing that had to be done on their phones. Looking at aspects of life through her lens is a window into her mind, and having a better sense of understanding her is part of my goal as a parent – even though she insists that I couldn’t possibly understand her! To a degree, she is right, though, I suppose.

TLC: That’s a very insightful sum-up of the pandemic-with-kids experience. It was excruciating at times, but also so connective. I love how you bonded as a family in your own idiosyncratic way. Do you see yourselves undertaking similar collaborative projects in the future? Or is this just a pandemic thing?

LK: Well, Ben and I had planned on working on a project about magic together. Without going into details, because a magician never reveals their (ahem) tricks, I will just say that making pictures together was never our strong suit, unlike his teachers Virginia Beehan and Laura McPhee. What we had settled on was I would photograph a certain strain within that subject that made sense for me, and the same for him, but a different thread. I predict we will pick that back up, but no big rush. I do love the idea of collaborating as a family again, somehow, but I feel like it would have to be right, and be organic. That is what happened with both of these book projects – they were not pre-planned. They just kind of happened in response to something we were going through. They had their own intelligence. I do encourage Ottilie to make pictures, and to draw borders on some of them, and have entered them in shows and publications that seem appropriate. I’m more like her manager, in that respect. She has actually gotten picked for a few cool things! (Matte’s recent “Exciting Photography Now” issue, and a local photo contest that happened to be blind-juried by Jim Welling, and more.) However, she tells me now that photography is “boring” and that she prefers drawing instead. So I guess that’s that. For now.

TLC: Kids often don’t want to do the things their parents do. Especially as they get into adolescent years and they have that need to individuate. At least that’s how it is with my kid. He wants nothing to do with photography. It will be interesting to see if it comes back around as they get older. I am thinking about these two projects in tandem. They are very different ways of making pictures. And conceptually different too. MOURNING deals with the tangible loss of loved ones, while IN captures the intangible loss of normalcy and freedom. The MOURNING pictures have a sense of form and control while the IN pictures are so alive and dynamic. Were these conscious choices to visually represent these different types of loss?

LK: No, again, I would say it all was form following content, but also content following form. They were all just made out of necessity, and luckily congealed into something. I guess both projects were about controlling something that was decidedly out of control outside of us. I don’t mean to reduce art-making to therapy, but for many of us, it’s just as much a part of our lives as breathing. Seeing is a natural sense, and we just have a compulsion to record slivers of that experience of our sight. And organizing the grids into pictures is compulsive, too, making order out of the chaos of one death after another. Even if IN appears to be much more fluid and less rigid, I guess there is still some kind of loose algorithm at play in the ebb and flow, and rise and fall of Michael Vahrenwald’s stab at tossing our 3 bodies of work all together. It’s sort of chronological, but also circular – which is I guess how that time felt anyway.

TLC: Yes, form following content and vice versa, the seesaw of art making. And of life. The way you intertwine the two with such raw authenticity is your superpower. I look forward to watching the story continue.

MOURNING by Lisa Kereszi is published by Minor Matters and includes an essay by Marvin Heiferman. The photobook is available for purchase through Minor Matters.

IN by Lisa Kereszi, Benjamin Donaldson, and Ottilie Leete is published by Roman Nvmerals and includes an afterword by Cindy House & an essay by Robert Storr. The photobook is available for purchase through Roman Nvmerals.

LISA KERESZI (b. 1973, Chester, Pennsylvania; lives near New Haven, Connecticut) received her BA from Bard College in 1995, and her MFA from Yale University in 2000. She is the author of four prior monographs: Fantasies (Damiani, 2005); Fun and Games (Nazraeli, 2009), Joeʼs Junk Yard (Damiani, 2012), and The More I Learn About Women, (J&L Books, 2014).

Keresziʼs work has been exhibited at numerous institutions, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New Museum, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the International Center of Photography, among others. Her photographs are in many private and public collections, including the Berkeley Art Museum; Museum of Fine Arts Houston; New York Historical Society; Whitney Museum of American Art; The Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Yale University Art Gallery. She is the recipient of a 2023 Tiffany Foundation Fellowship, a MacDowell Fellow, and was awarded the Baum Award for Best Emerging American Photographer in 2005.

Kereszi is a Senior Critic and the Assistant Director of Graduate Studies in Photography at the Yale School of Art, and from 2013-23 was the Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art. She is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery.

Follow Lisa Kereszi on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Kinga Owczennikow: Framing the WorldDecember 7th, 2025

-

Richard Renaldi: Billions ServedDecember 6th, 2025

-

Ellen Harasimowicz and Linda Hoffman: In the OrchardDecember 5th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025