One Year Later: Anna Rotty

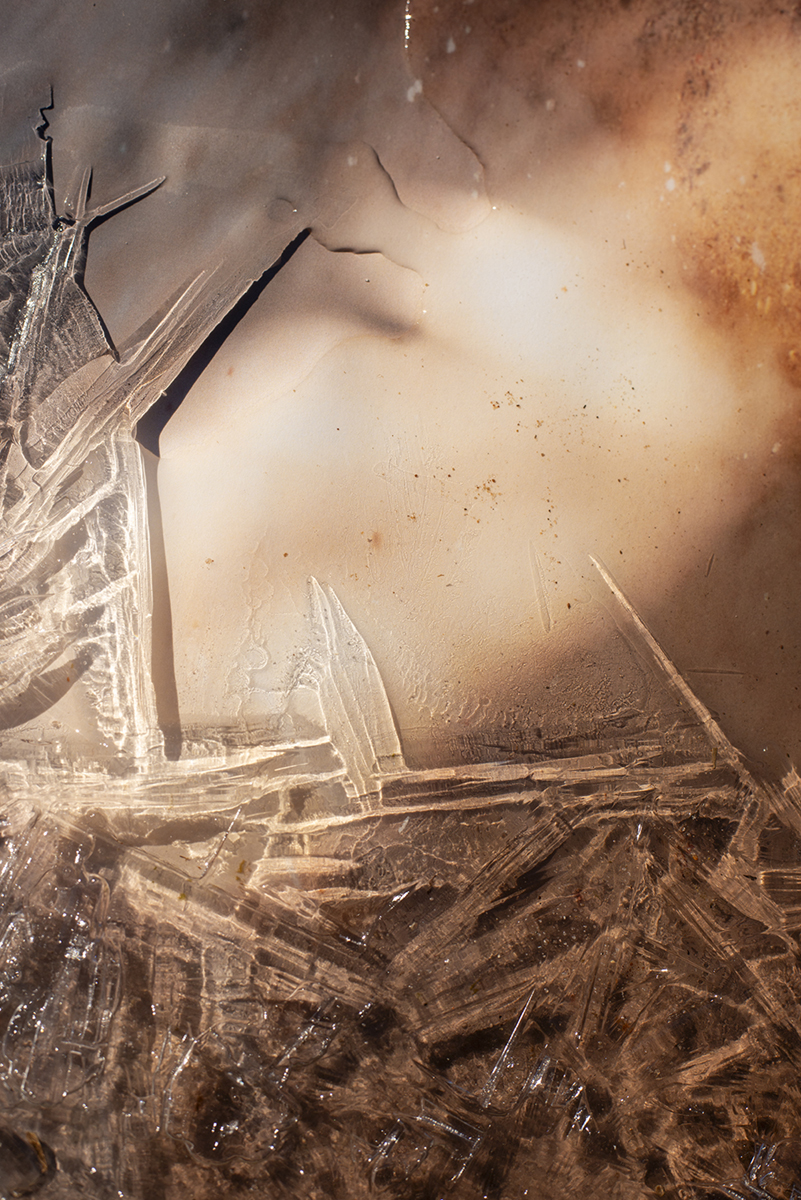

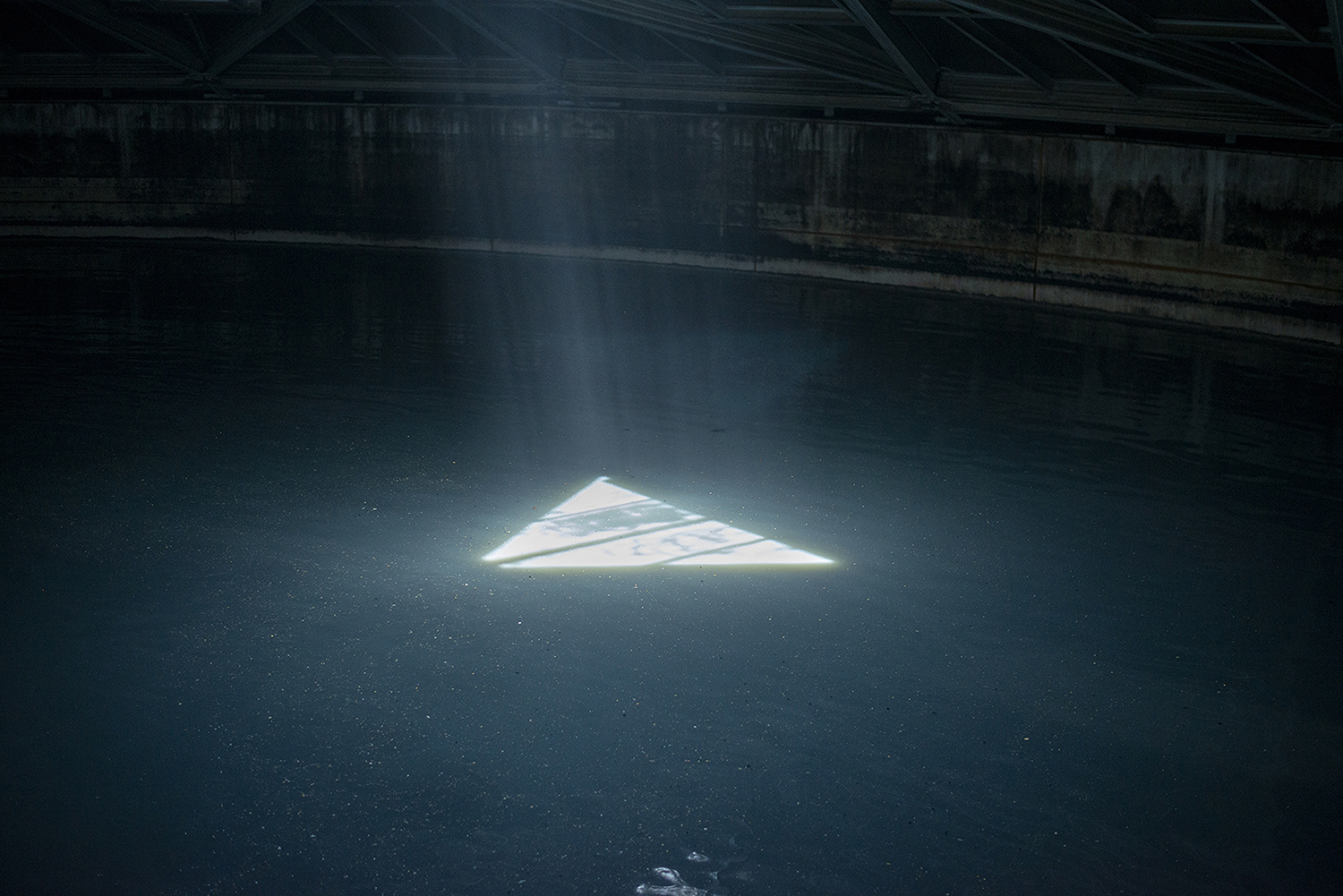

©Anna Rotty, As Above, So Below (Bernallilo County Wastewater Reclamation Center, Albuquerque, NM), pigment print photograph, 2023

Over the next three days, Drew Leventhal, the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner, interviews the Top 3 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners of 2023. He shares a conversation today with Anna Rotty.

I had been wanting to talk with Anna Rotty for a long while. We had been dancing in similar circles for the past year but had never connected. God, am I glad we finally got this chance to speak. Anna is a force of an artist, somebody who makes the simple combination of water and light into mesmerizing installations that brush against the outer edges of photography. She is clearly deeply attuned to the small ebbs and flows of the world around us, a common trait amongst great artists of any stripe.

In our conversation, we talk about how Anna’s process has shifted since her MFA program at the University of New Mexico. Hearing her describe the ways she is pushing the medium of photography gave me great hope for the future of our medium. Anna shows us that an artist’s practice can be fluid, taking many forms over time. It must also be eternally experimental. For Rotty, such experimentation has created an opportunity for a long and productive career spent exploring the world. — Drew Leventhal

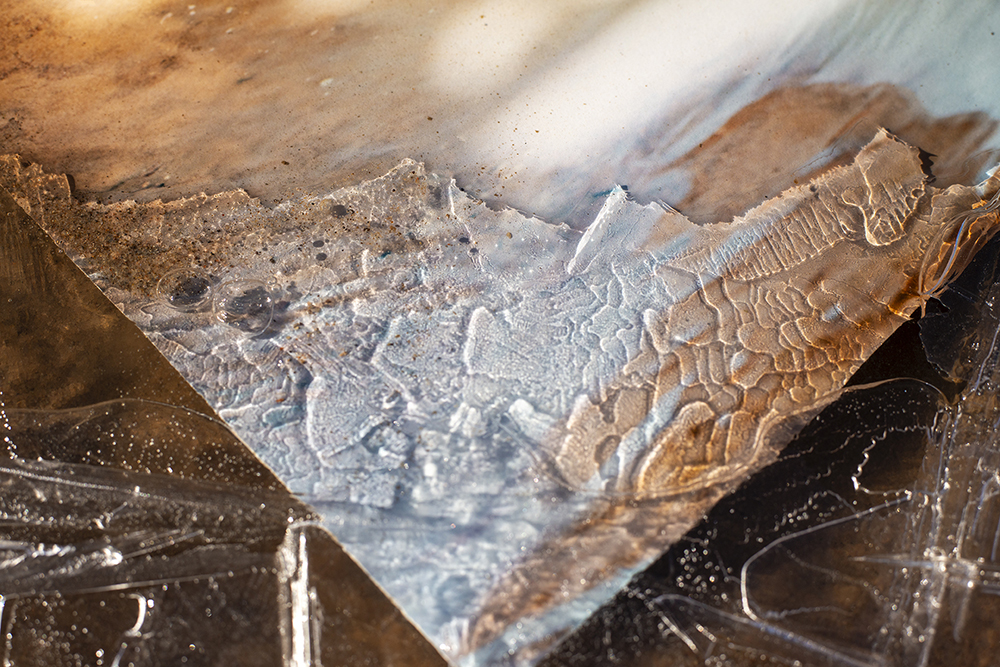

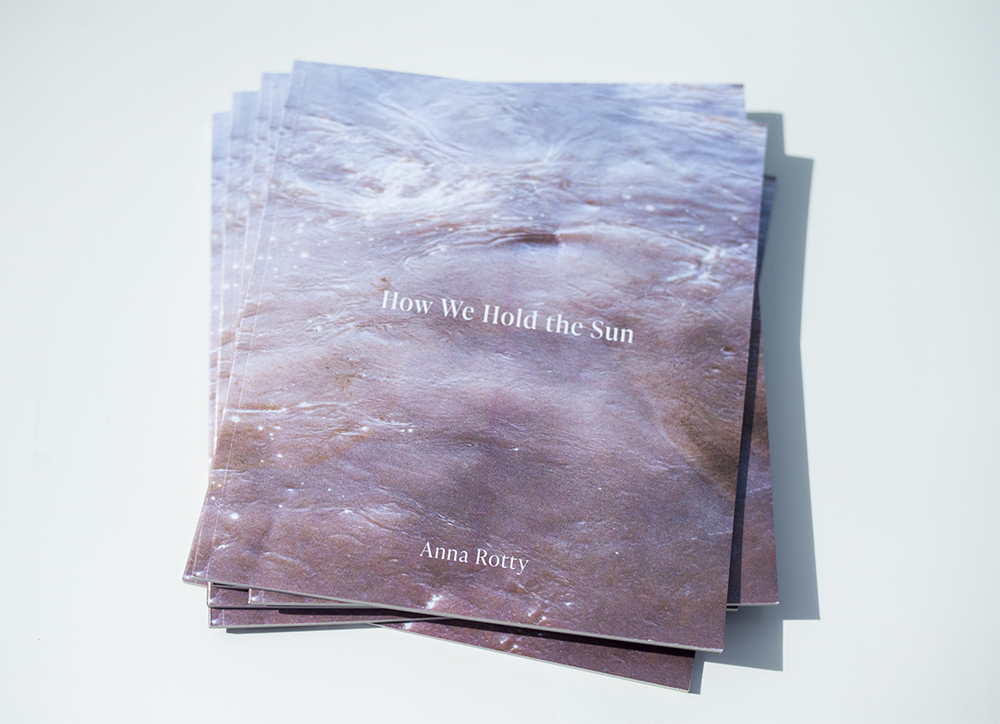

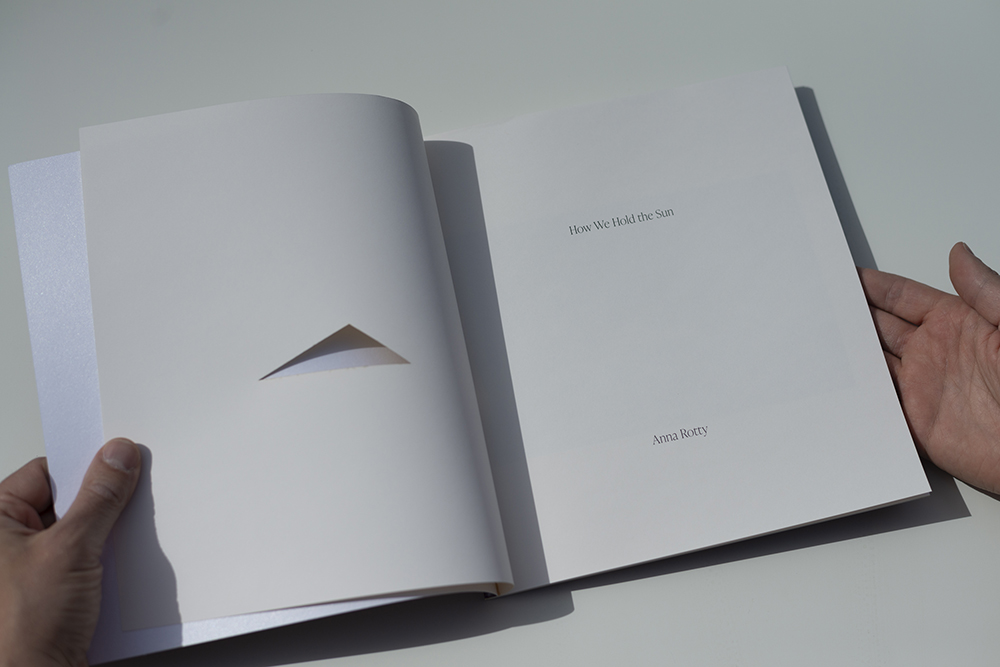

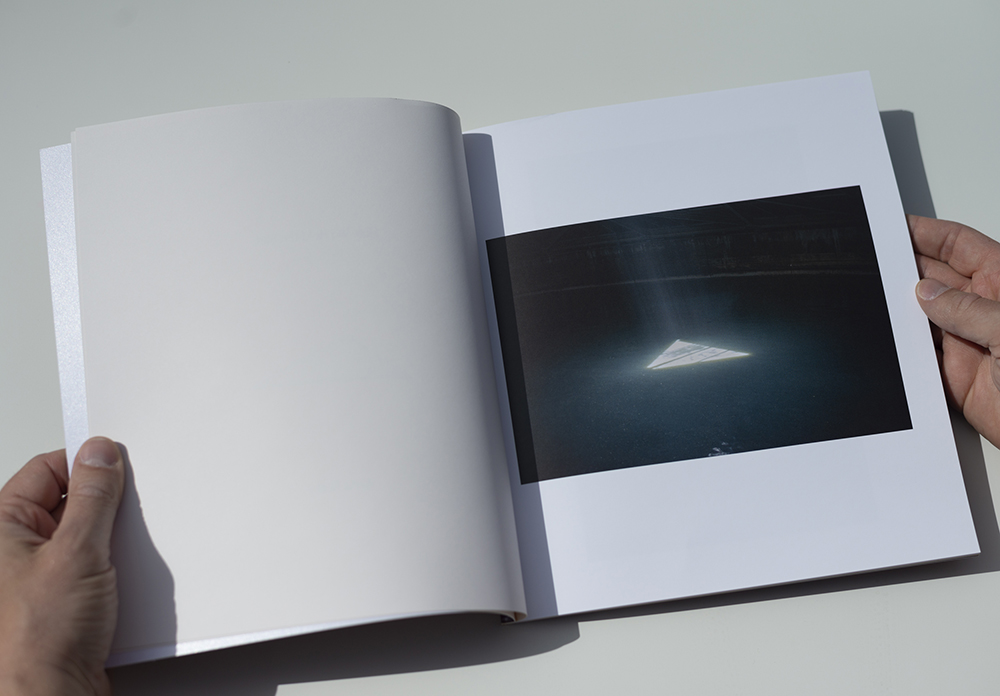

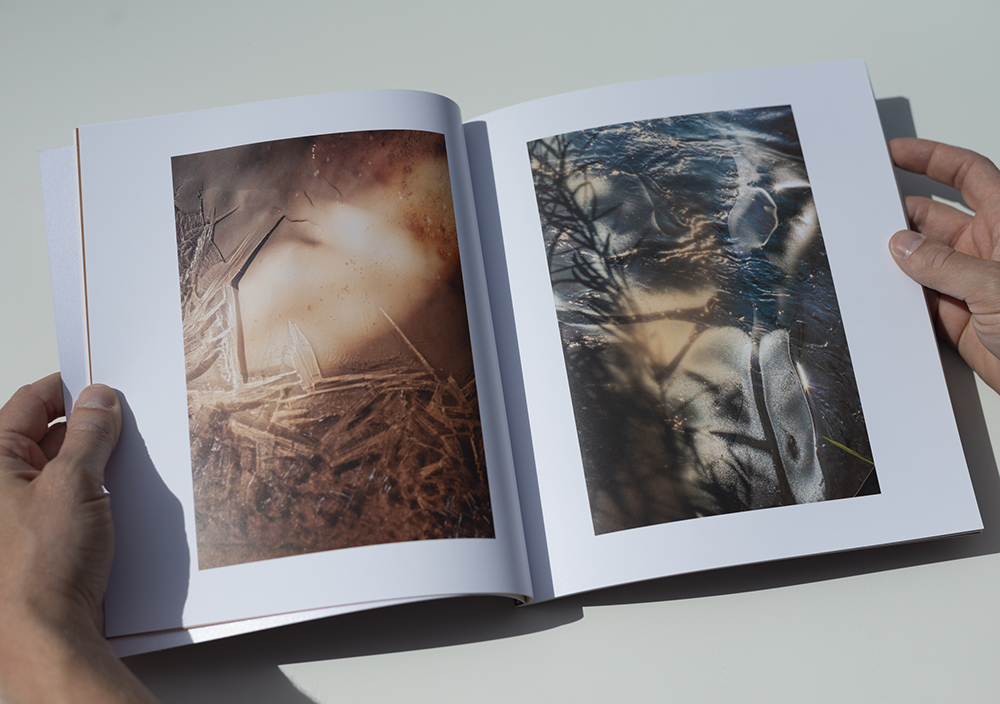

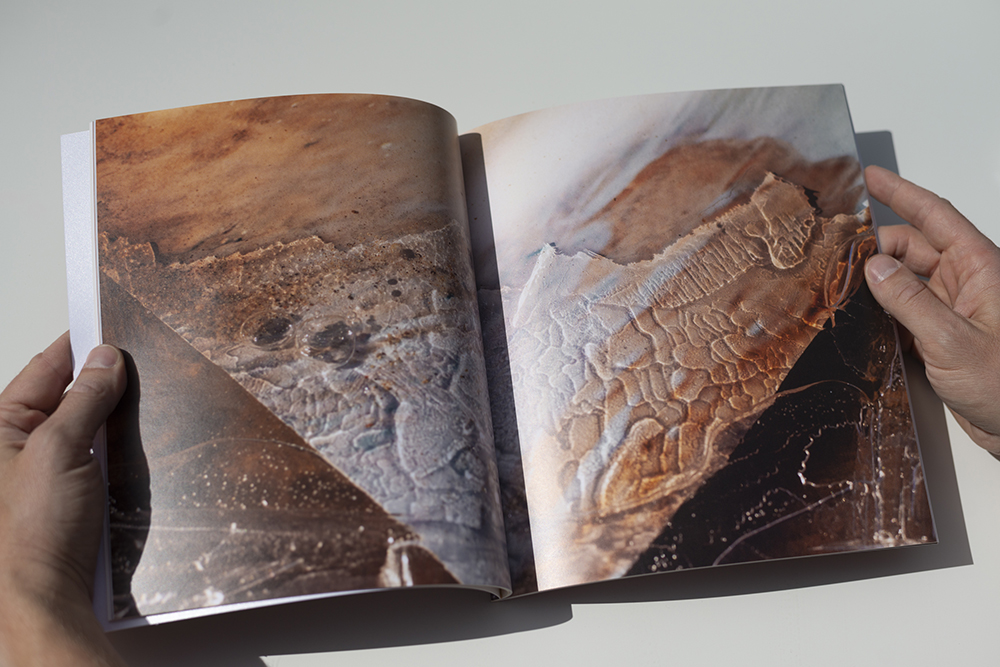

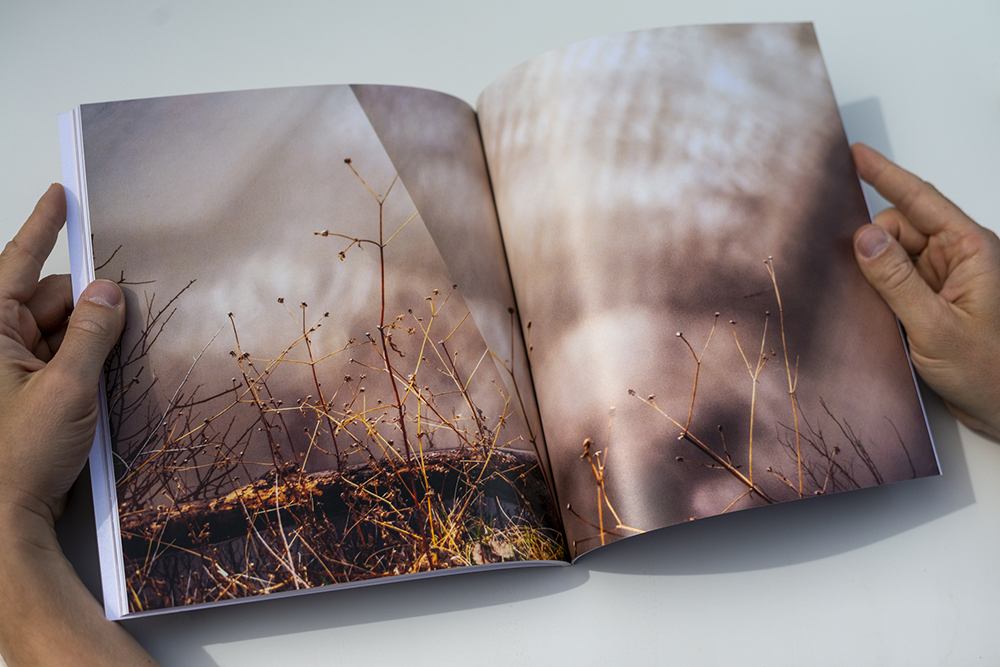

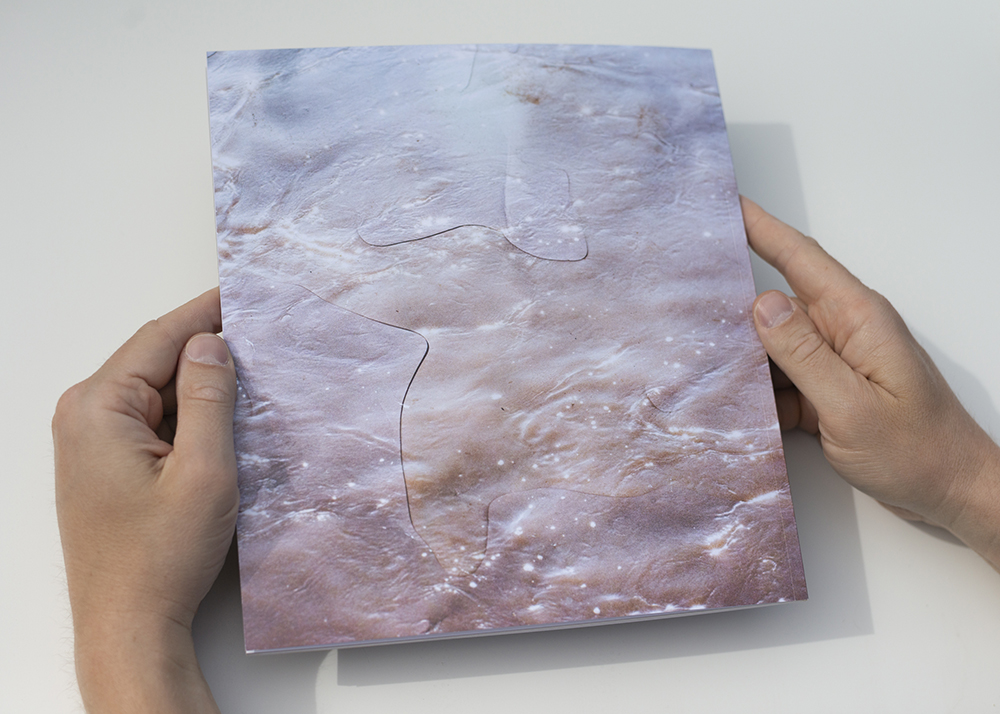

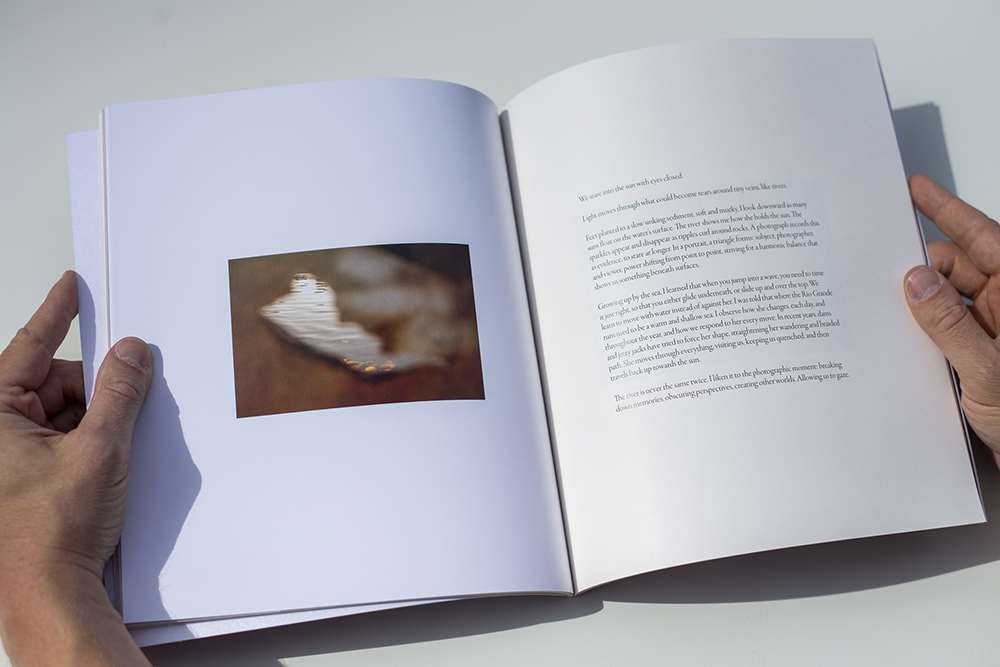

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

Anna Rotty lives on Tiwa land in Albuquerque. She earned her MFA in 2024, and currently teaches, at the University of New Mexico. Anna received a BFA from the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2011. Her work investigates water, light and infrastructure, informing her understanding of orientation and place. Her work has been published by Southwest Contemporary, Humble Arts Foundation, and Lenscratch, where she earned 3rd place in the Student Portfolio Prize in 2023. Anna is a recipient of the Silver Eye Center for Photography Fellowship 24 and has recently exhibited at Chung 24 Gallery in San Francisco, Strata Gallery in Santa Fe, and Northlight Gallery in Phoenix. Her work is in collections such as The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Library of Congress, and SFMOMA Special Collection.

Follow Anna Rotty on Instagram: @annarotty

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

My work explores the transformational and relational qualities of light and water. I’m fascinated by rivers as fluid beings, rather than fixed representations, with complicated histories – bodies representing power and agency, but also subject to attempts to control them. Growing up in the Northeast I spent my childhood getting to know myself and my body with large bodies of water. I learned that when you dive into a wave, you need to time it just right so that you move with it and not against it. Now, living in the desert, we carry a lot of anxiety around water. It is scarce, often fleeting and mistreated.

I observe, and then reconstruct my photographs in the studio, or within the environment, that investigate the systems, both natural and built, that transfer energy and water from place to place. My recent work consists of intimate portraits of the Rio Grande in Albuquerque, often shown as layered moments within a single frame. I search for places where light and shadow come together in the depths or hover on surfaces to illuminate sediment, rephotographing prints within the environment, showing the connection between landscape and body. In 2022 we witnessed the Rio Grande dry up for the first time since the 1980s. Seeing this, I spend time at the City’s Wastewater Treatment Plant, getting to know the cycles of water that contribute the 3rd largest tributary of the river. I invite the river to become a part of its own photographic representation, and hope my images serve as an active experience of landscape, rather than reiterating a passive gaze, as the medium of photography has historically so often portrayed the non-human ecologies of the West.- Anna Rotty

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

Drew Leventhal: Hey Anna, thanks so much for sitting down with me! Let’s dive in. Since you were part of the Lenscratch Student Prize last year, how are you doing? You said you just graduated from your MFA program?

Anna Rotty: Drew, thanks for talking with me! Having that opportunity to speak about my work in Lenscratch last year was really great. I had been slowly narrowing my research, focusing more specifically on the spaces and locations I live in in New Mexico as part of my thesis this spring. It was all of these ideas that were floating around that ended up settling on my obsession with the Albuquerque water system. I’ve had a really great last year of school at the University of New Mexico. It’s a three year program, so last year I was two thirds of the way through.

I got to put together a solo thesis show and an accompanying book. The book can kind of take whatever form you want it to take. My work tends to be sculptural so I thought of my book as a 2D version of the work. That was fun and challenging to put together. But I really like making books now.

I took a photo book class last fall, which was really great and helped me think about my own book. It was taught by Jim Stone, who has a collection of probably 5,000 photo books himself. He thinks a lot about books in all different forms and just loves photo books.

But you also love books too right?

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, self published book, 2024, 54 pages, perfect bound paperback, digitally printed photographs, laser-cutout pages, essay by Robin Babb, www.robinbabb.net

Drew Leventhal: I do love books, it has become a really big part of my own practice, publishing and printing and hand-making. Lets stay on this for a moment. What part of the process of bookmaking did you really enjoy?

Anna Rotty: I don’t think sequencing came naturally to me at first, even just choosing to put one or two images in a spread. I usually work iteratively. So I’ll go out and I’ll make photographs as sketches with my camera and that’s my way of observing, getting to know a place. Then I take those images and I start the editing process, which I love.

To shift a little bit, over the last few years I have actually begun to play more with those sketches, those studio prints. I’ve been bringing prints back to the river here in town, involving the water itself in shaping the photograph. The water would shape the print into something unique. I had been thinking about how water moves from place to place in a river, through pipes and infrastructure that we’ve built and how much of it is manmade or natural. Even the river is a super controlled space. Where in the show the prints live in different sculptural or installation forms, the book feels like an intimate experience of ideas I’d been swimming in. Some pages have laser cut shapes as a way to shape the light and give an active experience of looking, revealing and concealing. My friend and writer Robin Babb and I had been sharing similar thoughts about our work and she wrote a beautiful essay that’s included in the book. That collaboration and dialogue was a fun part of the process for me.

Drew Leventhal: I really like the way you are investigating these spaces that on the surface seem natural and organic until you realize that over time humans have stuck our hands and our designs into every little corner of the world. We try and shape nature but we often fail and make it worse.

Anna Rotty: Yeah, exactly. I think if you’ve seen Albuquerque, a lot of that infrastructure is visible on the surface of the Earth. I’m originally from Massachusetts and we have a whole different set of water problems. Lots of flooding in my hometown and the ocean pouring into houses from storms. Here in the West, all of this water infrastructure is out on surface level and you can see it, partly it’s the river itself. But then there’s diversion channels, acequias, and other man-made sections alongside it. And I became interested in that whole network. The Rio Grande is supposed to have a huge floodplain, which feeds the Bosque and all of the cottonwood trees. But again, now it’s very controlled.

This is kind of how I’ve been spending my time, trying to get to know the river and its complexities. Going back to the prints I am submerging in the water, I would bring those prints to the wastewater treatment plant. The wastewater treatment plant processes the city’s waste; around 50 million gallons of cleaned water goes back out into the river every day. It’s the third largest tributary of the Rio Grande.

Drew Leventhal: That’s incredible, I don’t think I realized it was that much water. All of it cleaned and processed and put back in.

Next 2 questions now: First, can you talk about the importance of installation in your work? Second, and this is a related question, can you speak to the influence that the artist Letha Wilson has had on your practice?

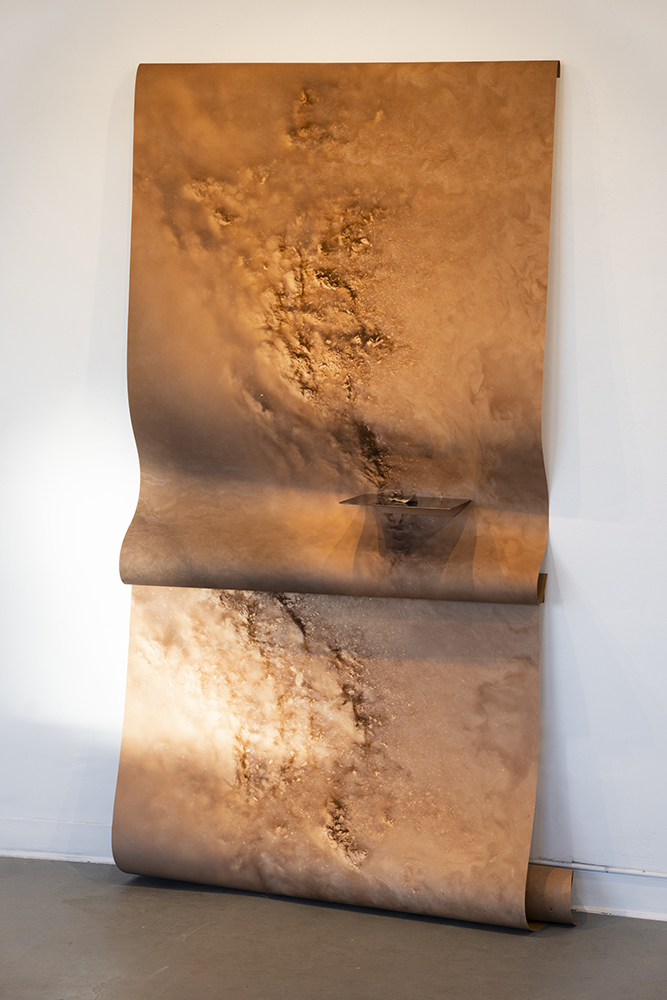

Anna Rotty: I like to think about how I can create more movement for people experiencing the work in a gallery space. It first started in grad school, where I had a lot more resources that I’ve had in the past. So I was able to take a sculpture class and learn how to build my own frames and build things in ways that didn’t exist in the world. I also started grad school in 2021, so we had just been spending so much time on Zoom and everything that I was looking at was flat on the screen. I got really excited about wanting to see things from different angles and viewpoints. So I started making big prints, and printing on the backside of the paper. There’s a piece in my thesis show that I call Sun Bent Sediment, and it’s kind of a version of one of the pieces that I shared with Lenscratch last year that was a waterfall of composited images, both prints and transparencies. For the newer piece, I made a scaled up version of a small section of the turbid brown moving water of the Rio Grande and let the paper cascade down the wall. In one spot it’s pinned to the wall with a bent mirror that holds a delicate dry mud flake I collected when the river was totally dry. I want people to be drawn to look close, to look behind and down and up above their heads and think about the way this physical piece of dirt is a version of what’s in the photograph. If it were to fall into the background it would melt away and transform again. Light is a whole other thing that I am excited about in physical space, how it can change a work over the course of a day.

Drew Leventhal: What I find so interesting is that people react very differently to photography and sculpture. There’s different visual languages involved. There’s a sense of scale with the big prints that become these sculptural objects. And in some ways that really ties into what you’re talking about with the power of the water. We have so much reverence for the print on the wall but when you take it out of the frame actually and do things to it, bending it or putting it into different frames or putting it into different locations, the meaning changes so much. You have so many more options.

Anna Rotty: Yeah. And I think those options feel surprising to me. I’m learning just by doing and arranging things in different ways. I’m learning from it in a way that I wouldn’t if it was just a print. Sometimes I think it’s about that tension of having certain things, or representations, live in certain forms at different moments in time. I’m trying to get away from the idea that something is ever done or complete.

Drew Leventhal: I was wondering if I could add one word to what I was just saying, which is the idea of wonder. It comes up a lot in sculpture but less so in photography. I was wondering if you think that your work has a sense of wonder to it?

Anna Rotty: I love that word. Wonder. I think it goes hand in hand with curiosity, asking just how do things work? I think wonder has a lot of power to make us look at things longer, look at things from different angles, question things. It allows us to sit in uncertainty.

Drew Leventhal: I like that you use the word curiosity because it fits into my simplistic motto for what an artist is. Whenever somebody asks me what an artist is supposed to do I always say that we are professionally curious about the world. I just want to understand the world in some way. I just happen to do that through photography. So I like what you just said; your job is to be curious about the Rio Grande and how it works and to make art about it.

Anna Rotty: Thanks. Yeah. And I think you mentioned Letha Wilson too so let me address that question. So I’ve never seen her work in person – yet! I’ve seen it online though and I admire what she has done. The piece that comes to mind is the one where the print cuts through the column in the room, it’s called Ghost of a Tree.

©Anna Rotty, Sun Bent Sediment, double-sided pigment prints, bent acrylic mirror, dry mud flake from Rio Grande, 2024

Drew Leventhal: Yes, that’s the one, alongside Moon Wave, which is rather similar.

Anna Rotty: That piece got me thinking a lot about the structure of a space and how something can kind of intercept it or live among it. And I think we need more of that versus trying to make the art separate from the space or us separate from the environment.

Drew Leventhal: That actually ties into my next question, which is great. What I wanted to ask is, and this is probably part of being at UNM, which has a long tradition of working with landscape, but I’m wondering how you feel that your work challenges the history of landscape photography, especially in the West?

Anna Rotty: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I’ve been thinking about that a lot over the last few years. Living here in New Mexico did make a big difference around how I think about landscape. At UNM, I think because of where we are and it being in the West and with the many Pueblo and Diné communities who are here as sovereign nations and have been caring for the land since well before settlers colonized or photographs circulated, I feel a responsibility to reshape how photography has contributed to representations of land. I took a class called Native Art and Feminism with Dr. Marcella Ernest, and she talks about how we’re engaging with our work through process, over the product or end result. I also took a class called American Landscapes with Dr. Kirsten Buick, and that was really eye-opening in terms of how the whole history of art in the U.S. shaped control of land. For example, the Hudson Valley School created paintings that promoted manifest destiny. I think reflecting on these histories helped validate some of the ways that I was creating and eliminating certain ways of looking.

I naturally like to look closely at things and photograph very up close with no horizon line. It lets you get lost in this abstract frame. I really didn’t want to create an image that people could enter into as easily. That’s also where the sculptural elements come in, the work becomes a being or entity that you can’t just view, you have to move around and engage with it differently.

©Anna Rotty, Sun Bent Sediment, detail, double-sided pigment prints, bent acrylic mirror, dry mud flake from Rio Grande, 2024

©Anna Rotty, Sun Bent Sediment, Installation View, 1415 Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, double-sided pigment prints, bent acrylic mirror, dry mud flake from Rio Grande, 2024

Drew Leventhal: There’s two points that I want to touch on. One is, you just mentioned the idea of process, the “how” leading to the “what,” and it’s related to something that I’ve been thinking about a lot recently. In photography, so much of the thinking and theory around it is rooted in the end result, the photograph, the product, right?. The photograph is all of these things at the end of the process. But we actually speak very little sometimes about the process, what photographers actually do. So I’m glad you brought that up.

The other thing that I wanted to talk about was the idea of scale in your landscape. You mentioned that you like to work close up. That seems pretty antithetical to these traditional landscapes, which as you said, have been pictured and painted broadly to understand and control the land. I’m thinking of Paul Virilio here, looking down onto the wide landscape from above as an act of controlling it.

But what you’re doing feels like the radical opposite, to zoom way far in. I like what you said about the eyes almost becoming unsettled. They can’t really land anywhere. In some ways it’s the land refusing to be viewed and controlled. We lose in a way.

Anna Rotty: Thank you. Absolutely. And I do kind of want us to lose, or I dunno if it’s losing, but learn something? I guess just lose a little bit of our control and our power so that the agency is then put back into the land and water itself. I get excited looking at images that offer that destabilization. I like to be a little confused about what I’m looking at. I want to see things change, or, I want to be responsible for noticing things change, if that makes sense. I want to go to the river and see and know that it looks different than last time because I don’t want to take it for granted.

©Anna Rotty, *Photo Credit: Sean Carroll (Silver Eye Center for Photography), Installation View, Fellowship 24 Exhibition, Silver Eye Center for Photography, Currently Showing through August 3, 2024

Drew Leventhal: This actually ties in really well into my next question, which is about a project that you didn’t share with Lenscratch. I want to talk about your Terra project, which I really loved when I was looking at it. Can you describe, just for the reader, what you were doing to create these kinds of landscapes and why you felt that it was important to make these, again, really small scale landscapes that look rather expansive.

Anna Rotty: Sure, thanks. Those were made starting in 2020. I was photographing a lot in my house. This is the very beginning of the pandemic, and I was living in Oakland, and the sun would come in through the window in the morning and move across the room throughout the day.

I eventually got sick of photographing the same things in my house. I had this emergency blanket that my dad gave me. I needed to change the way that my house looked because it was just getting really stale and stuffy, so I started using that blanket to bounce light around in different ways. It started rather naturally but I got more and more controlled about what was in the frame, using a roll of paper or the wall as a backdrop to construct these landscapes. It felt like a ritual to me, just a way to deal with all of this uncertainty and anxiety around not knowing what’s going on in the world. It was kind of this space that I could escape into. The light was really important in that work. I haven’t talked that much about light, but I feel like light is critical, for all photographers.

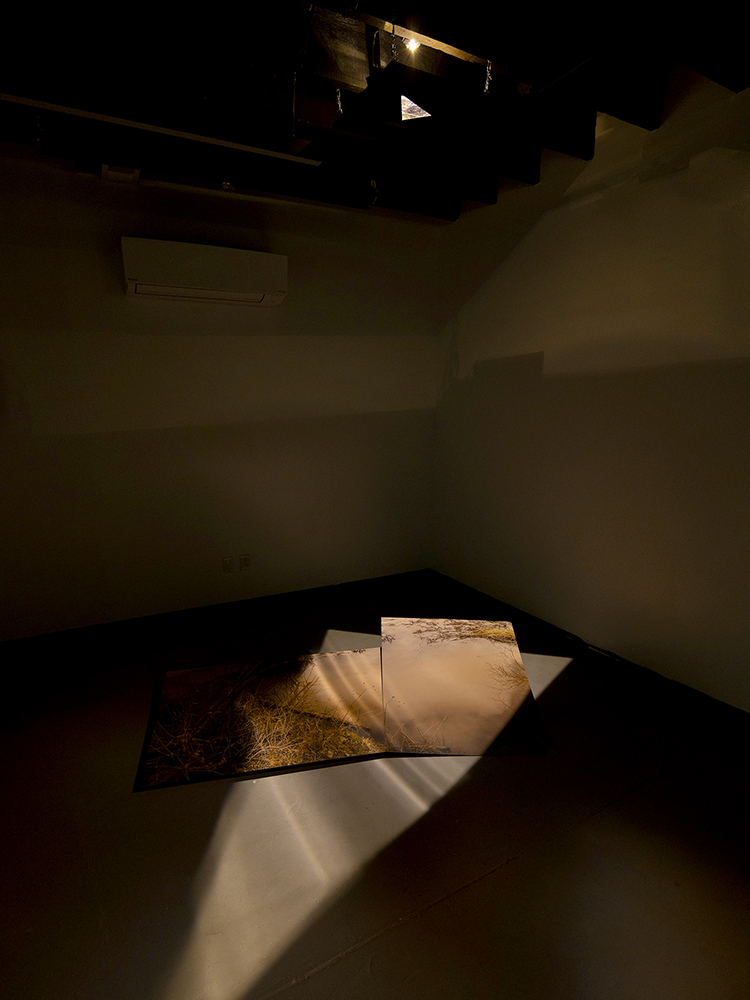

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, installation view, Alpaca Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, photographs mounted on aluminum displayed on floor with hidden braces, light fixture with agitating moving water trays, 2024

Drew Leventhal: It’s so important to what we do. For you it becomes almost another sculptural piece. And that actually segues perfectly into our last subject: your thesis exhibition. Can you tell us more about some of the pieces and what they depict or represent or allude to?

Anna Rotty: I was thinking about the river and about light, how they can interplay with each other. So for my show, I had a “light room” and a “dark room”, two gallery spaces that were next to each other. The light room had lots of windows and throughout the day it was subject to whatever the sun was doing in a lot of ways. Beams of light would come in early in the morning, and then it would kind of be ambient all day. And then at night, beams would reflect off of this window across the street and bounce into the gallery, illuminating a sculptural piece. That space held more traditional photographs in 2D form and a few sculptural pieces.

In the dark room I had photographs mounted on aluminum displayed on the floor, and they were all close up photos of the Rio Grande, mostly the bank of the river. Hanging above them I built these light fixtures that were carrying clear trays of water. The water was agitating and evaporating over the course of the show, creating patterns on the prints and the floor. This was a new venture into installation that I’m really excited about. I’m thinking about how a photograph can be more than the representation of something. Water and light let me do that in this room. And so the light fixtures are projecting the movement of water. It is not a video projection, it is light through actual moving water.

©Anna Rotty,How We Hold the Sun, installation view detail, Alpaca Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, photographs mounted on aluminum displayed on floor with hidden braces, light fixture with agitating moving water trays, 2024

Drew Leventhal: How are you agitating the water?

Anna Rotty: The water is agitated with a servo motor. I had to learn all new mechanical and sculptural stuff in the last few months before my thesis. And I got a lot of help from friends thankfully. So there’s a spotlight that is up above this moving tray of water, and when you’re looking at it from below, it becomes like an enlarger. The motor lifts and releases the tray agitating the water from side to side.

Drew Leventhal: Yeah, definitely like an enlarger.

Anna Rotty: They’re these enlargers and the water is creating the photograph with movement. So this felt like a way to show my process of what’s happening when I’m out in the environment with a print and the sun is casting through trees and the water is moving over the print and it’s creating these projections. So I really wanted to make that actually happen in the gallery space. And it was kind of nice because the placement of the prints on the floor were so big that you couldn’t stand directly underneath the light source and people’s shadows couldn’t intercept it.

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, installation view detail, Alpaca Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, photographs mounted on aluminum displayed on floor with hidden braces, light fixture with agitating moving water trays, 2024

Drew Leventhal: That’s really cool. I think about the way we can utilize light and optics. Like you said, your installation ended up being something larger symbolically speaking. There’s also a lot of potential to the idea of making images on location, in the gallery. The image making process becomes the practice or the piece itself.

Anna Rotty: Another cool thing that I didn’t really anticipate: I used water that I collected from the river, so it had some sediment and cottonwood leaves in it. And one of the seeds started growing algae. People were like, “What’s in there that looks like a body or something?” I mean, it’s growing. It’s alive. The water would evaporate and I would have to refill the installation with new water. That water has a lot of calcium in it so it would leave these calcium deposits. So now I’ve been contact-printing those patterns in the dark room and they’re these photograms of the residue or the evidence of this life.

Drew Leventhal: Wow, that sounds incredible and I think it’s a perfect place to end, with the wonder of what comes next. I am excited to see those new images. Thank you so much for sharing with us Anna!

©Anna Rotty, How We Hold the Sun, Exhibition Installation Shot, 1415 Gallery, Albuquerque, NM, “light room” in thesis show, 2024

Drew Leventhal (b. 1995) is an artist and anthropologist concerned with notions of community, historiography, and ritual. Working in an ethnographic style, his images engage with contrasting ideals of imagination, lineage, life, and death. Drew holds a BA in anthropology from Vassar College and an MFA in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. His work has been featured in numerous publications and has been exhibited across the United States. Drew’s project Mason & Dixon was awarded the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize and he has been a finalist for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, the PHMuseum Grant, and the Film Photo Award. Drew is currently based in Philadelphia, PA.

Follow on Instagram: @drew_leventhal

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025