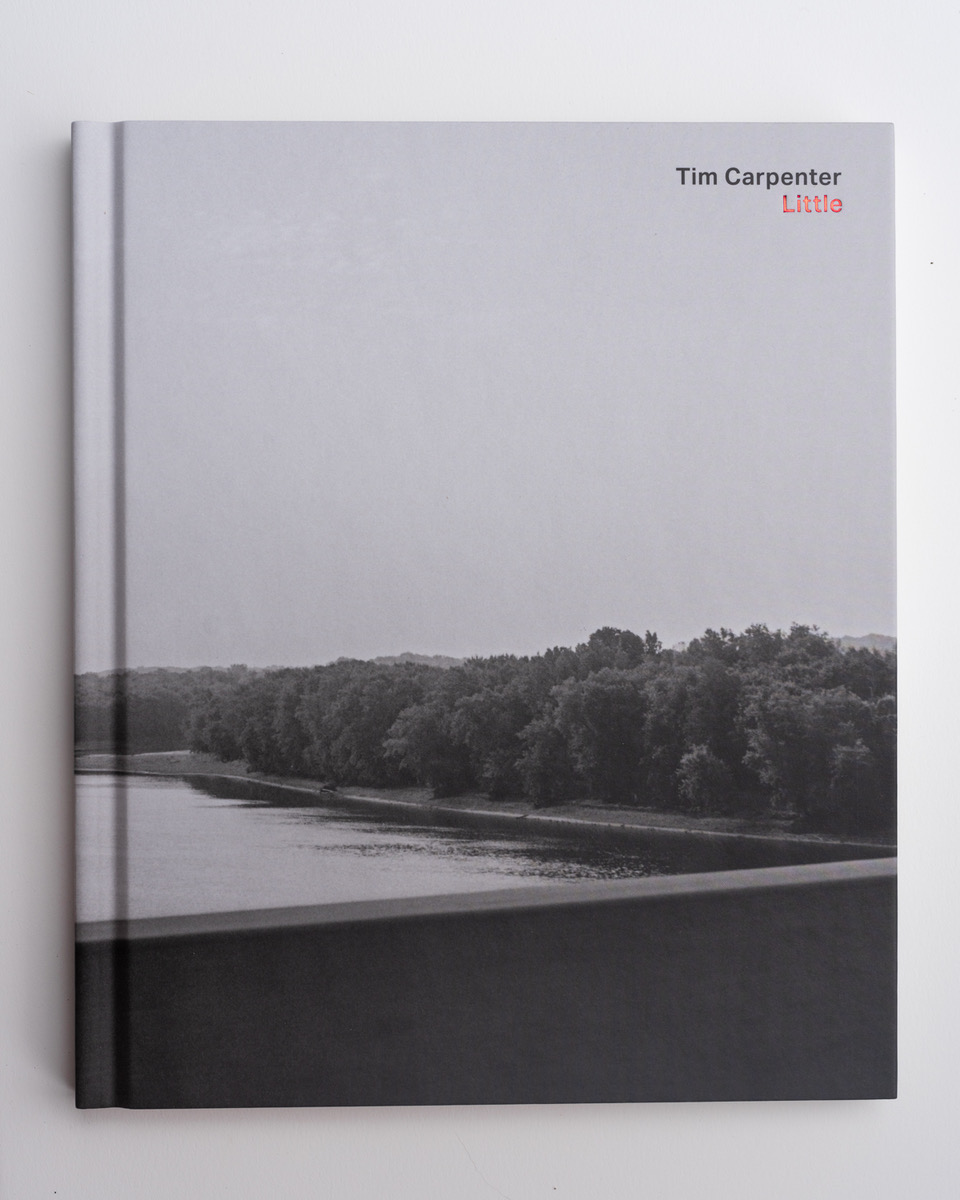

Tim Carpenter: Little : The Ice Plant

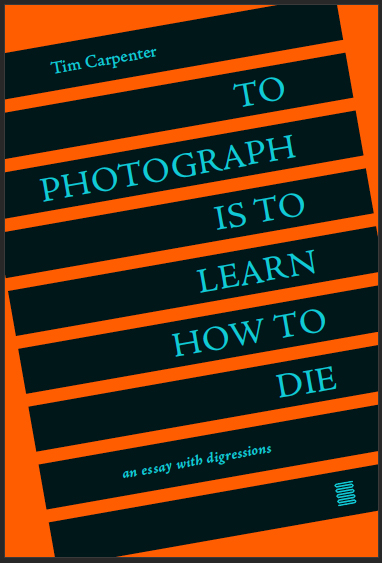

Tim Carpenter’s newest photobook, Little, completes a trilogy of books published by The Ice Plant that are composed of photographs made in and around his hometown in Central Illinois. In Little, Carpenter channels the perspective of a child, meandering and open to meaning and possibility within each encounter. Carpenter’s photographs transcend conventional narrative, urging us to see the world unburdened by preconceived notions—a journey back to the pure, unfiltered curiosity of youth. Coming off the heels of his popular essay To Photograph is to Learn How to Die, also published by The Ice Plant, I was curious to see how Carpenter’s theory would connect to his practice, the pictures being where the rubber meets the road.

The following is a conversation between Tim Carpenter and Tracy L Chandler

TLC: Where are these pictures made? And what is your relationship to this place?

TC: The vast majority were made in my hometown of Monticello, Illinois. A few were made on drives around the local area.

My dad was in the Air Force, so we moved around a lot when I was a kid. I mostly grew up in Ohio. My folks moved back to Monticello permanently only when I was in college. So although I know the town well, I didn’t go to school there and I don’t know tons of people. It’s an interesting place for me – there are aspects of me that are both insider and outsider.

TLC: Interesting. How did photographing there change that feeling of belonging. Did it bring you more in or create more distance?

TC: More distance, but that’s not the town’s fault. I think that’s a general theme in my life: maintaining a wary distance. Probably mostly because of being gay, and way before I even had that word or was sexual. A dislocation or estrangement. The title Local objects came after my first book was pretty much set; the first line of the Wallace Stevens poem really twisted the knife: “He knew that he was a spirit without a foyer.”

TLC: That line! Cuts right to it! And home often comes with a sense of ambivalence. I know it does for me, at least. I understand Little is part of a trilogy with Local Objects (2017) and Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road (2019) both are also with The Ice Plant. How does this book pick-up where the others left off?

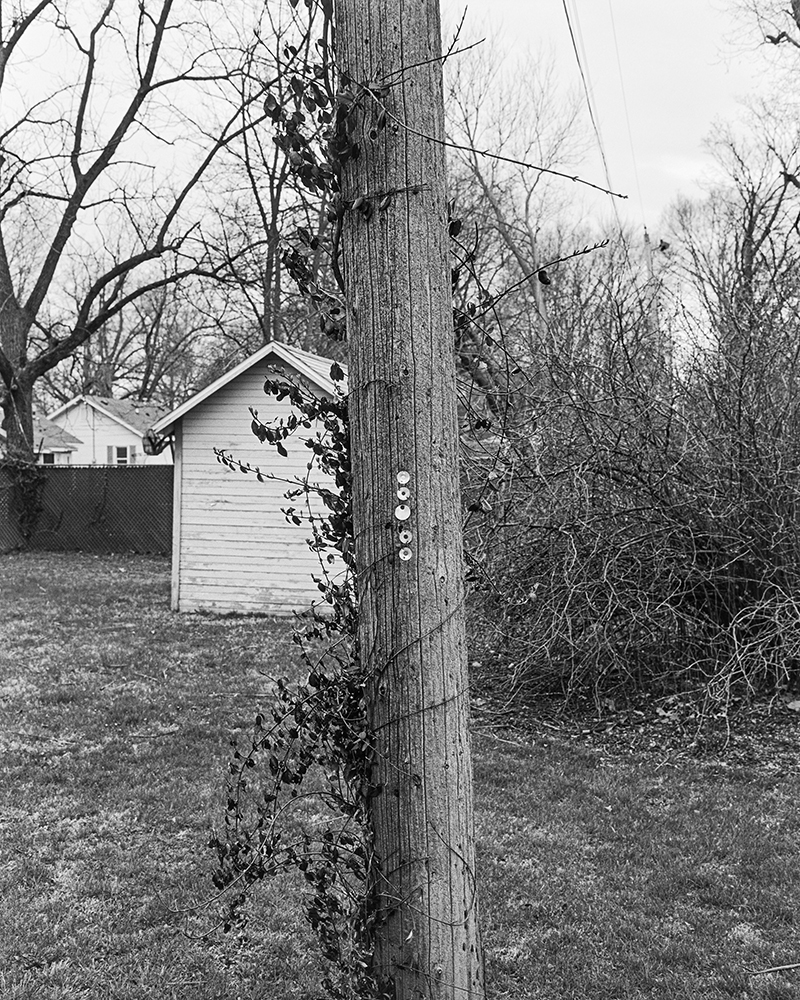

TC: Back when Local objects was just a set of a couple hundred pictures, Brad Zeller looked at them and said they were like “a thousand lonely walks home when I was teenager.” Not only did that encapsulate my general feeling, but it gave me some structural specifics to work with in the edit and sequence: repetitive movement through space over time. And also an age for my ‘protagonist,’ an idea which has become very important for me. In this case, I decided that this 15 or 16-year-old aspect of myself was bereft of a world of signs or symbols – so I got rid of everything in the subject matter that spoke of something outside of the picture: mostly things like skateboards and basketball hoops and bicycles. Back then I thought that those photographs could eventually have a different life, and they sort of did, but in a different way, as I’ll get to.

I kept playing with the idea of different aspects of myself, with specific ages and life situations – and thus specific pictorial structures – in books like township (a collaboration with Raymond Meeks, Adrianna Ault and Brad Zellar) and The king of the birds, both published by TIS books.

Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road then represents another aspect of me, but one from which I could not get much ‘objective’ distance. I was mired in a bit of a funk – nothing much more or less than we all experience – and I couldn’t make sense of my position vis-a-vis the world. And my pictures from that time absolutely manifested that. So it was just a lesson to me that sometimes we project and create our world, and sometimes the world pushes back and we are “decreated” (using a word from Simone Weil via Wallace Stevens and Anne Carson).

Anyway, I had always still been thinking about those symbol-laden pictures that had been cut from Local objects, and a shift occurred as I was going on long picture-making walks with my nephew. For a small kid, just about every mark or trace is a potential sign. I became much more interested in those nascent symbols, and how the imaginative faculty makes sense (or not) of them. And of course the failure of my own imaginative faculty in Bucks Pond Road. That all kind of comes together in Little.

TLC: I get what you mean. It’s almost as if we need to reach back to a more innocent version of ourselves to really see, let go of the cerebral projections that come along with being an adult, and get out of our own way. When we are young, everything is new and that novelty holds our attention. For me, the Little pictures have a different quality of attention than the others. The gaze seems more focused and yes, the objects hold more meaning. Were you looking for any particular signs or metaphors? How were you able to get out of your own way and see the world differently?

TC: I love the way you say that: get out of your own way. That’s pretty much the concept of decreation that I’ve written about – to tamp down your projections onto the world. To see things rather than concepts. I should say that I don’t think that’s 100% achievable, but that there’s great value in the attempt, at least for me. I want to make photographs with no prose equivalent – no narrative story that could be spun out of them about people and places and situations. I like those kinds of pictures as a viewer, but I’m not interested in making them.

Which meant that I (with great help from Tricia Gabriel and Mike Slack) had to be really careful with the edit for Little. I wanted to catch that moment when the potential sign is still nascent – where it’s merely salient (it’s not nothing), but where it’s also without linguistic ‘meaning.’ Anne Carson calls this the third place, between chaos and cliche.

TLC: That sounds like a lovely and also terrifying place. I feel like humans like to make our world recognizable, to name things, to feel like we know. But as you say that “third place” holds all the potential. It hasn’t yet been collapsed into a definable bit.

I am looking at the pictures again and at first glance they may seem banal. Black and white images on a gray day. A pair of garage doors. But if we just pay attention there is wonder and mystery in the mundane. Why are the leaves only raked on one side of the driveway?.. Is this pointing to a solo inhabitant? My question for you is not about this photo specifically, it’s more about the source of that mystery. Is that feeling of wonder inherent in the content of the photograph or inherent in our quality of our attention?

TC: That’s a fundamental question. I believe that the photograph is purely denotative, and that any and all connotations occur in our heads, in that quality of our attention, as you say. (On this, of course, there is much disagreement.) And that’s what makes it so powerfully different from all other communicative forms, which necessarily have connotative elements built into them – the conventions of sign systems in language or in the ‘hand of the artist’ in the other graphic arts. Barthes was right when he called the photograph a “message without a code;” all other forms are conventionally coded, at least to some degree. He also said – and this has gone spectacularly unremarked upon – that because of that distinction, the ethic of the photograph is different from the ethic of the drawing or from any other form. Which for me means that the ethic of camera work is also absolutely unique.

To bring this back around to your question, that’s the mystery or wonder in the mundane – when we are in a proximate relationship to a thing in its absolute singularity (an ethical relationship – to adapt Levinas – that only the camera allows), outside of concept or category, it is indeed a wonder, a mystery. Photographic denotation for Barthes is a “madness” and an “ecstasy,” and again he is correct.

TLC: Yes, the movement is on multiple axes – within in the pictures, and across the sequence. For instance, in the beginning of the book we start on one side of the tracks and by the end we end up on the other side. Our view is now looking back. For me it seems to connect the wandering childlike perspective you spoke of with your reality of midlife. A time when we start to look back. When we have more days behind us than ahead.

TC: I appreciate that reading; I want it to evoke the perceptions of both youth and middle age, somehow simultaneously.

TLC: I am curious about the timing of this work in relation to your essay To Photograph Is To Learn How To Die, also published with The Ice Plant. Were you making these pictures whilst writing? Or were they more siloed acts of creation? How did one affect the other?

TC: Well, the picture-making was separate; all of the photographs in Little were made by 2019, before I started writing the book. However, the final edit and sequence are both rather recent, and that essential aspect of Little is absolutely intertwined with To photograph, and also with a follow-up book that I’m researching and writing now.

In the past few years, I’ve learned a lot about literary theory and language theory and sign systems, as well as phenomenology and embodiment, and all of that has certainly influenced how I’m thinking about photographs. It hasn’t so much changed the way in which I make pictures – that’s still pretty much free-wheeling and in the moment – but there’s a different sort of rigor in the initial editing of contact sheets and absolutely in the edit and sequence of anything I would show to anyone or publish. It’s sort of a paradox: I have a “concept” for my shaping of photobooks – and that is for them not to employ or rely on any linguistic concepts. “No ideas but in things” means for me: “No photographs or books of already-existing ideas.”

TLC: This approach is paradoxical! In the best way. And “No ideas but in things” is from the context of poetry. Doesn’t photography work a little differently? The things, or the images of things in this case, are inherently visual. They are not verbal statements. They are pointers. They can provoke the ideas but not declare them with words. Ah. Here we are with the denotations and connotations again. We have come full circle! On that note, can I ask one last question? Earlier we discussed Little as part of a trilogy. How does it serve as a conclusion for you? Or does it not? Will this work continue?

TC: It’s not really a ‘conclusion’ in any narrative sense; these books aren’t in any particular order; in fact they skip around in terms of the ‘age’ or life situation of the ‘protagonist.’ The trilogy part is that these are my three proper monographs – singular statements – with the same publisher, and I like the way they collectively define a way of looking at the world that’s grounded and yet changes over time.

Everything else I’ve put out has been either a collaboration (township, Still feel gone) or a part of a bigger set (The king of the birds, Illinois Central, A house and a tree), but all of those are intertwined too, as a sort of long-term arc. I’ve always felt that if there’s any ‘project,’ it’s me working with a camera; occasionally I look back at the pictures and see if there’s something to yank out of them and make something of.

Little by Tim Carpenter is published by The Ice Plant. The photobook is available for purchase through The Ice Plant website along with a special edition that includes a pigment print. The essay To Photograph is to Learn How to Die is also available from The Ice Plant.

Tim Carpenter is a photographer, writer, and educator who works in Brooklyn and central Illinois. He is the author of several photobooks, among them Christmas Day, Bucks Pond Road; Local objects; Bement grain; and The king of the birds. He holds an MFA in Photography from the Hartford Art School and is on the faculty of the Penumbra Foundation Long-term Photobook Program.

Follow Tim Carpenter on Instagram

The Ice Plant is a photography book publisher located in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Ice Plant on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026