Andy Mattern: Ghost

Lenscratch recently held its annual(-ish) call-for-projects, and the response was impressive. In total, there were over 500 submissions. We are eager to look through each of these entries and share some highlights over the months to come. Today I am in conversation with Andy Mattern about his project Ghost.

Andy Mattern is a visual artist working in the expanded field of photography. His photographs and installations dissect the medium itself, reconfiguring expectations of photography’s basic ingredients and conventions. His work is held in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the New Mexico Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, among others. His photographs and exhibitions have been reviewed in publications such as Artforum, The New Yorker, Camera Austria, and Photonews. Currently, he serves as Associate Professor of Photography at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. He holds an MFA in Photography from the University of Minnesota and a BFA in Studio Art from the University of New Mexico.

Instagram: @andymattern

Ghost

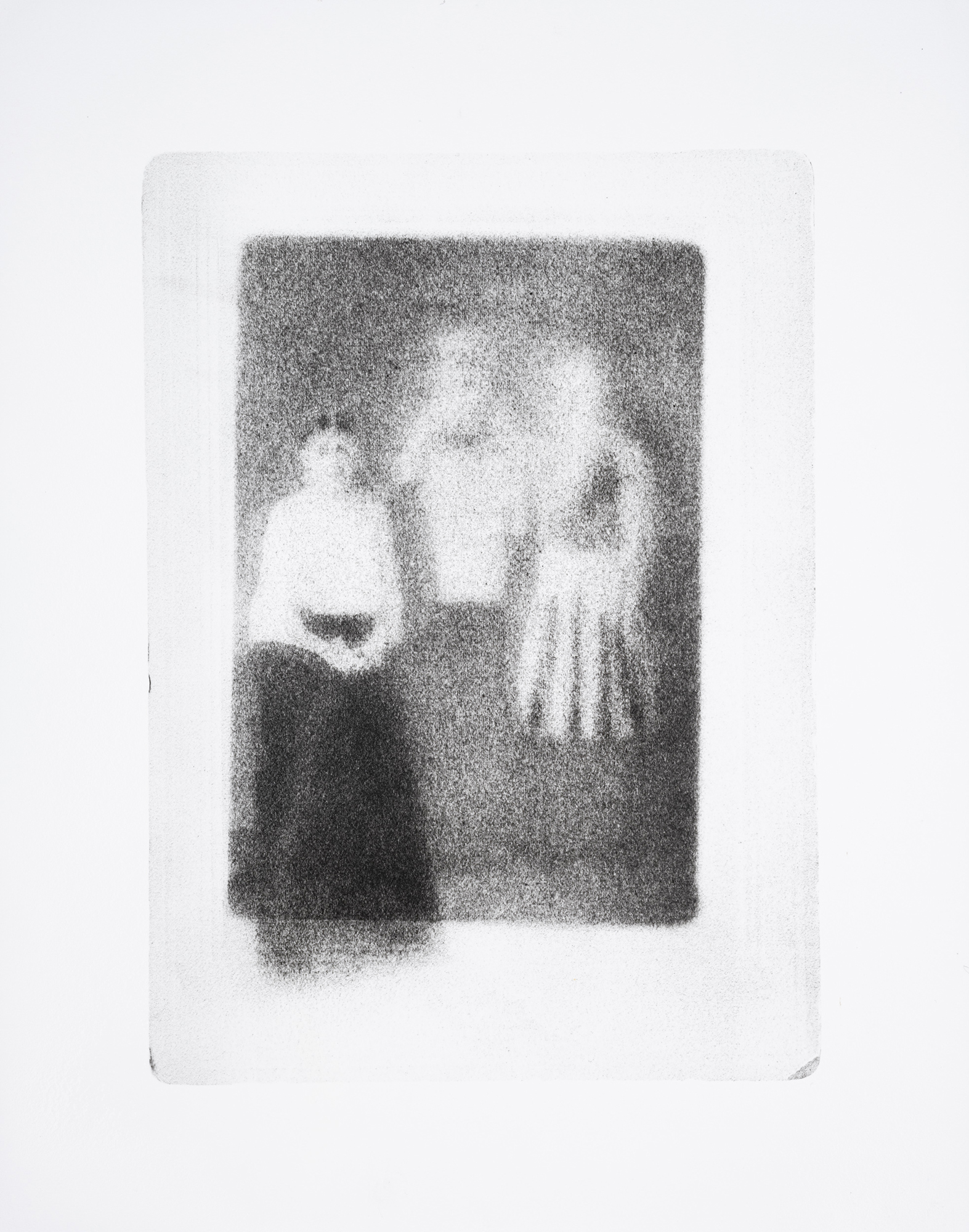

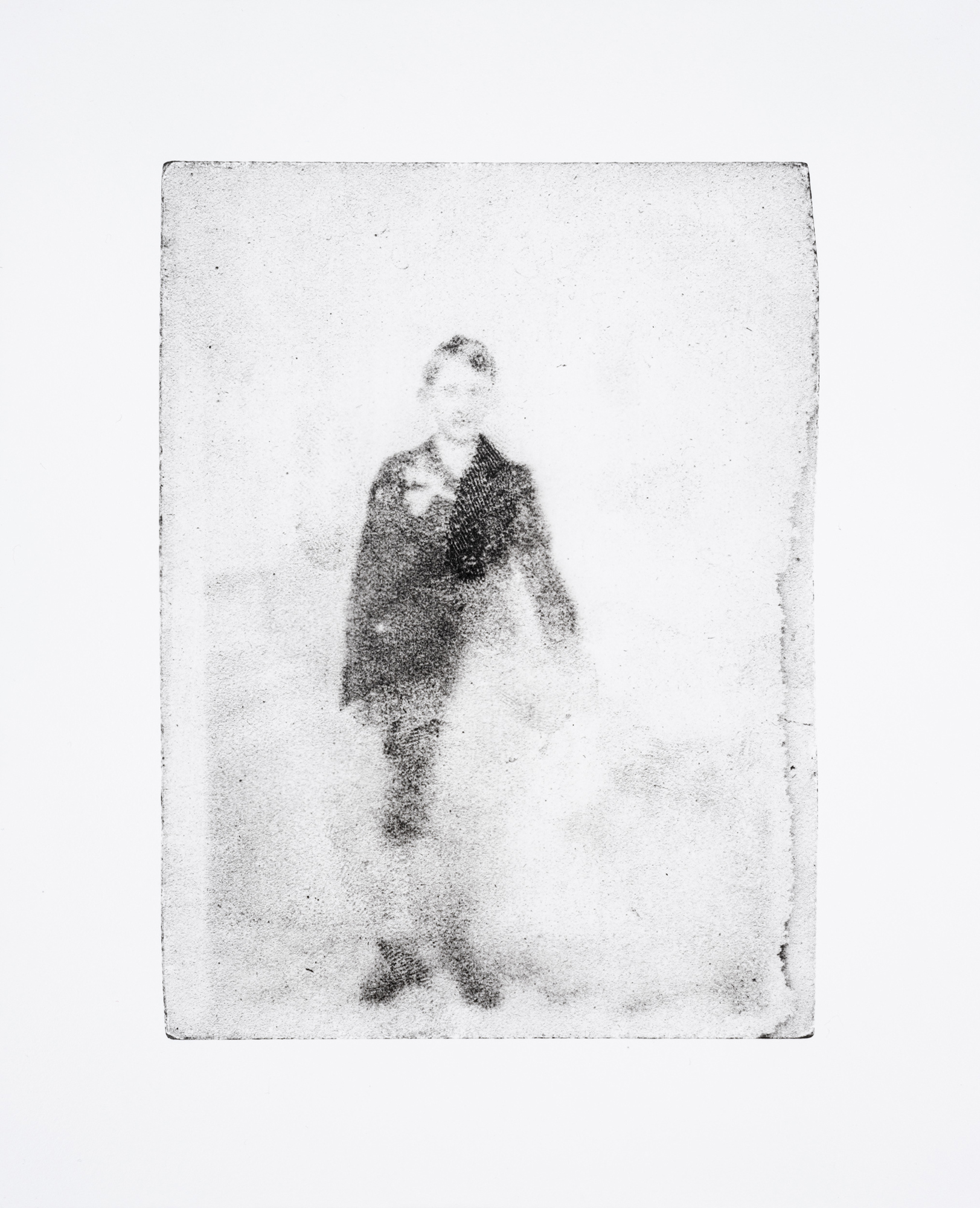

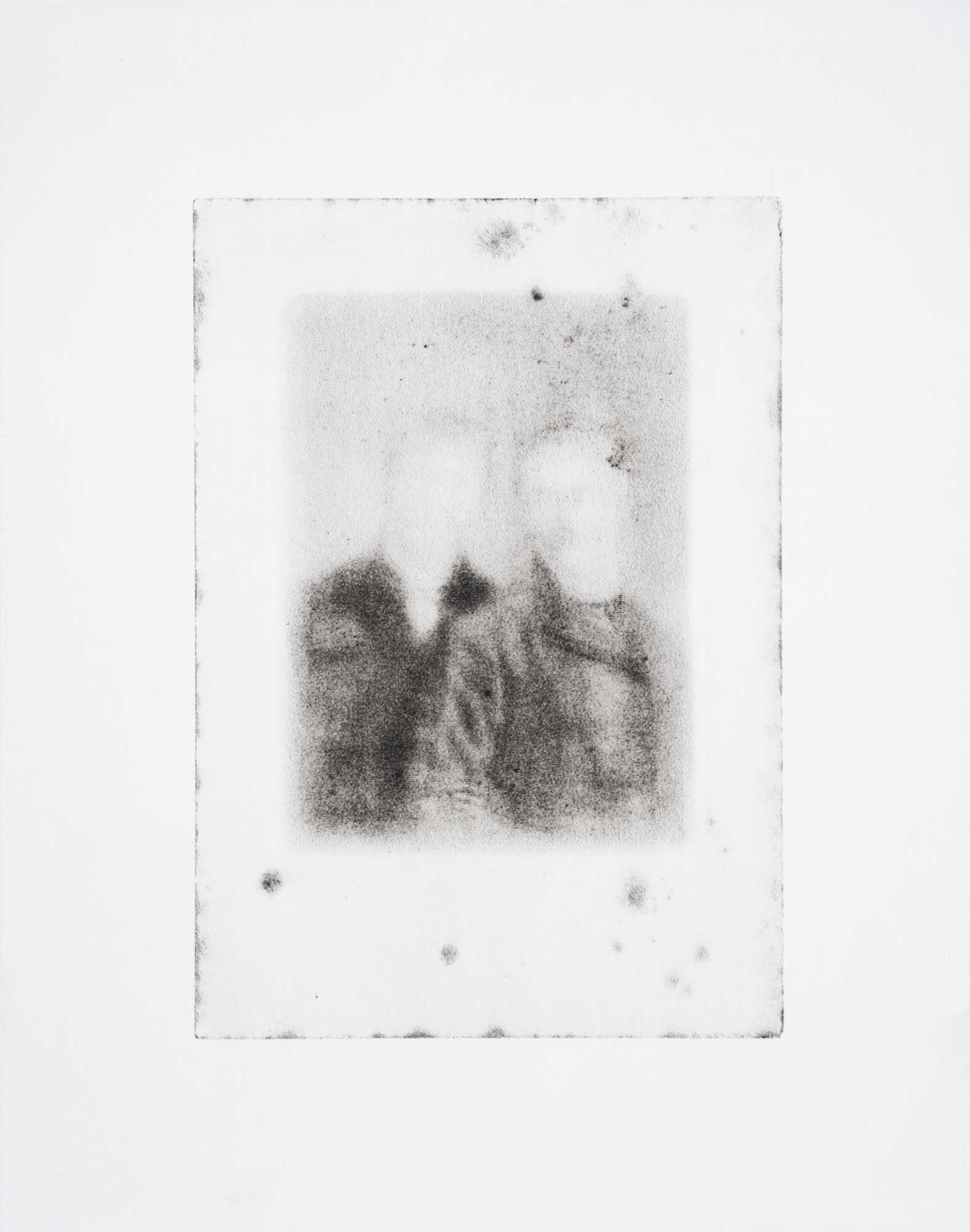

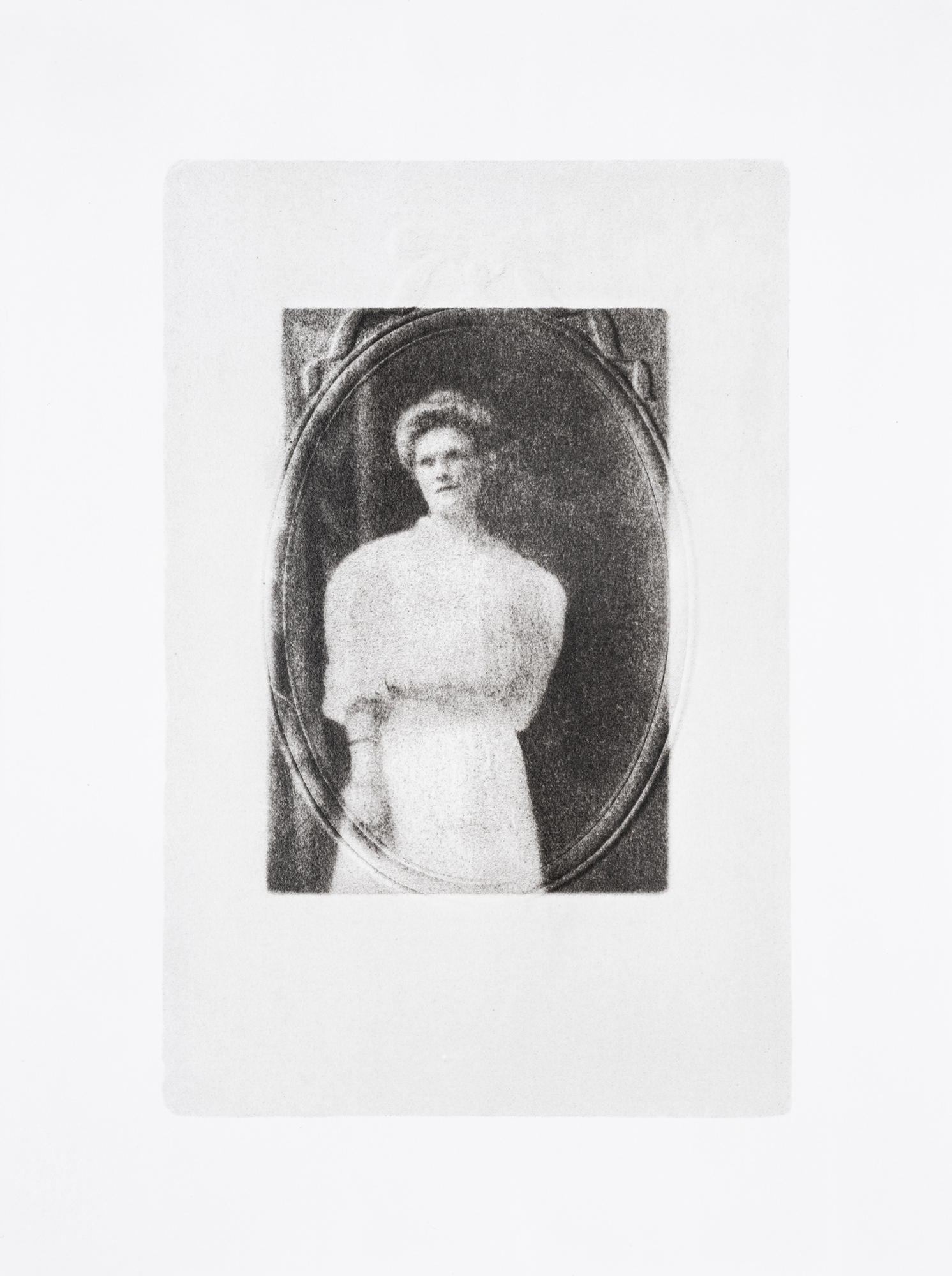

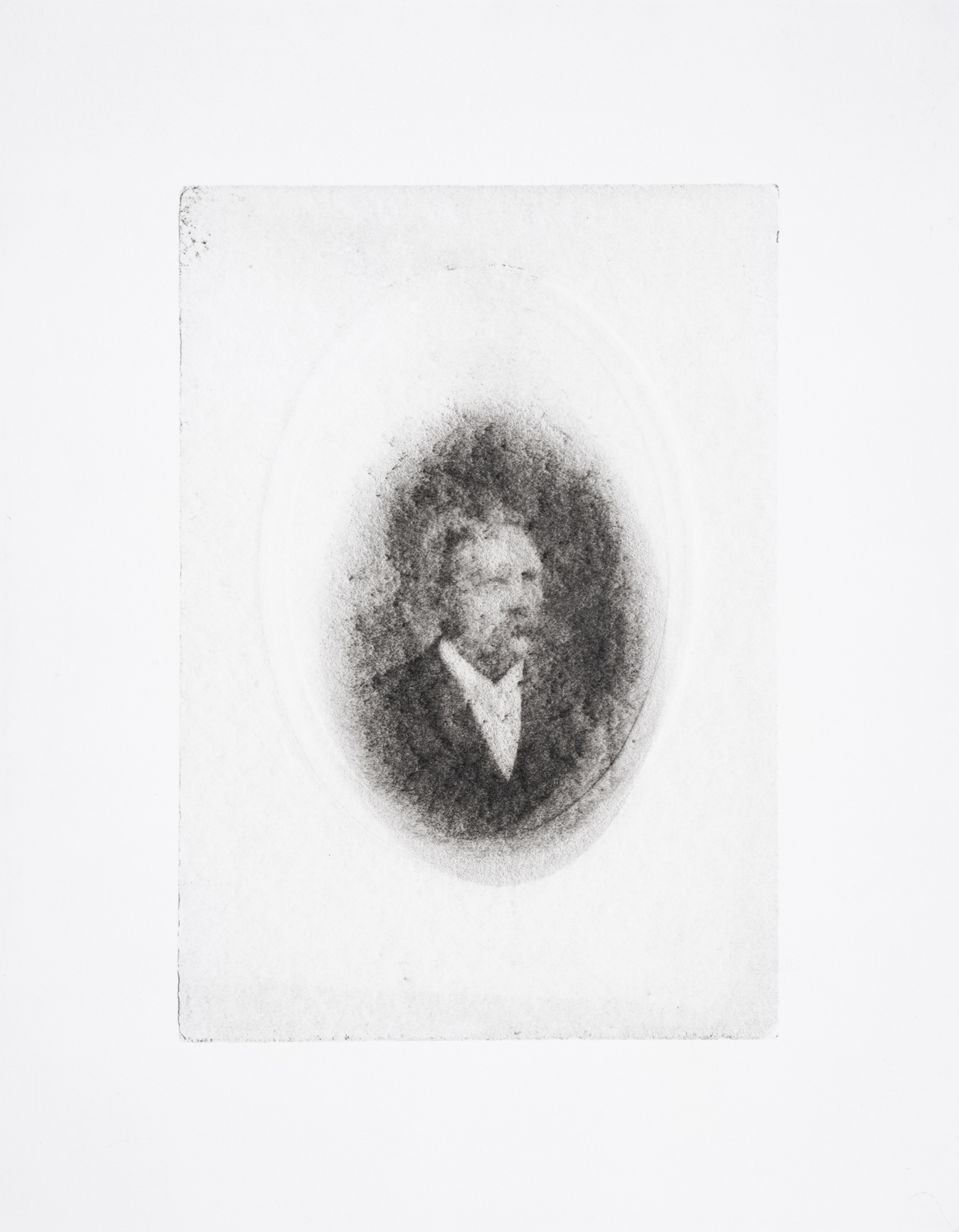

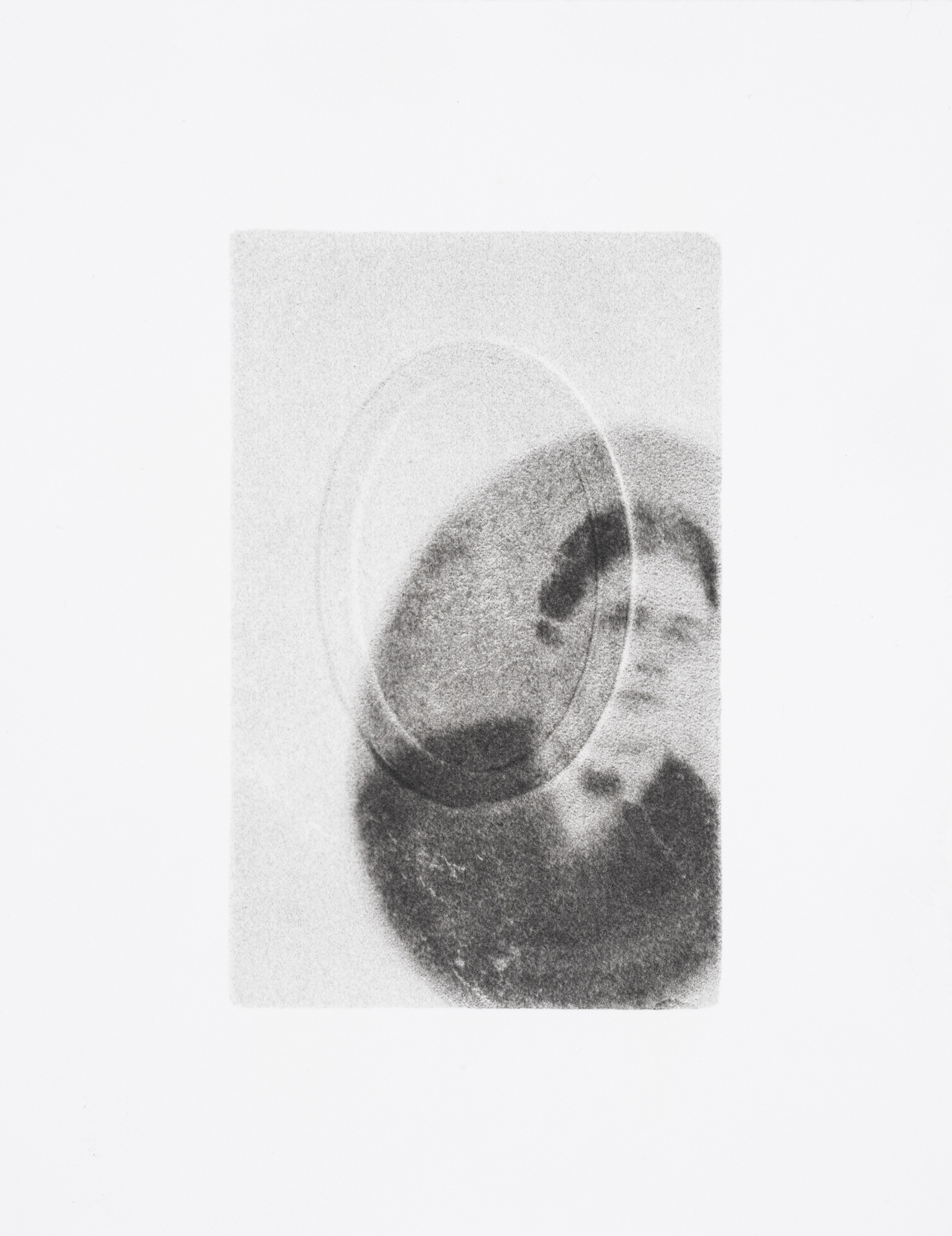

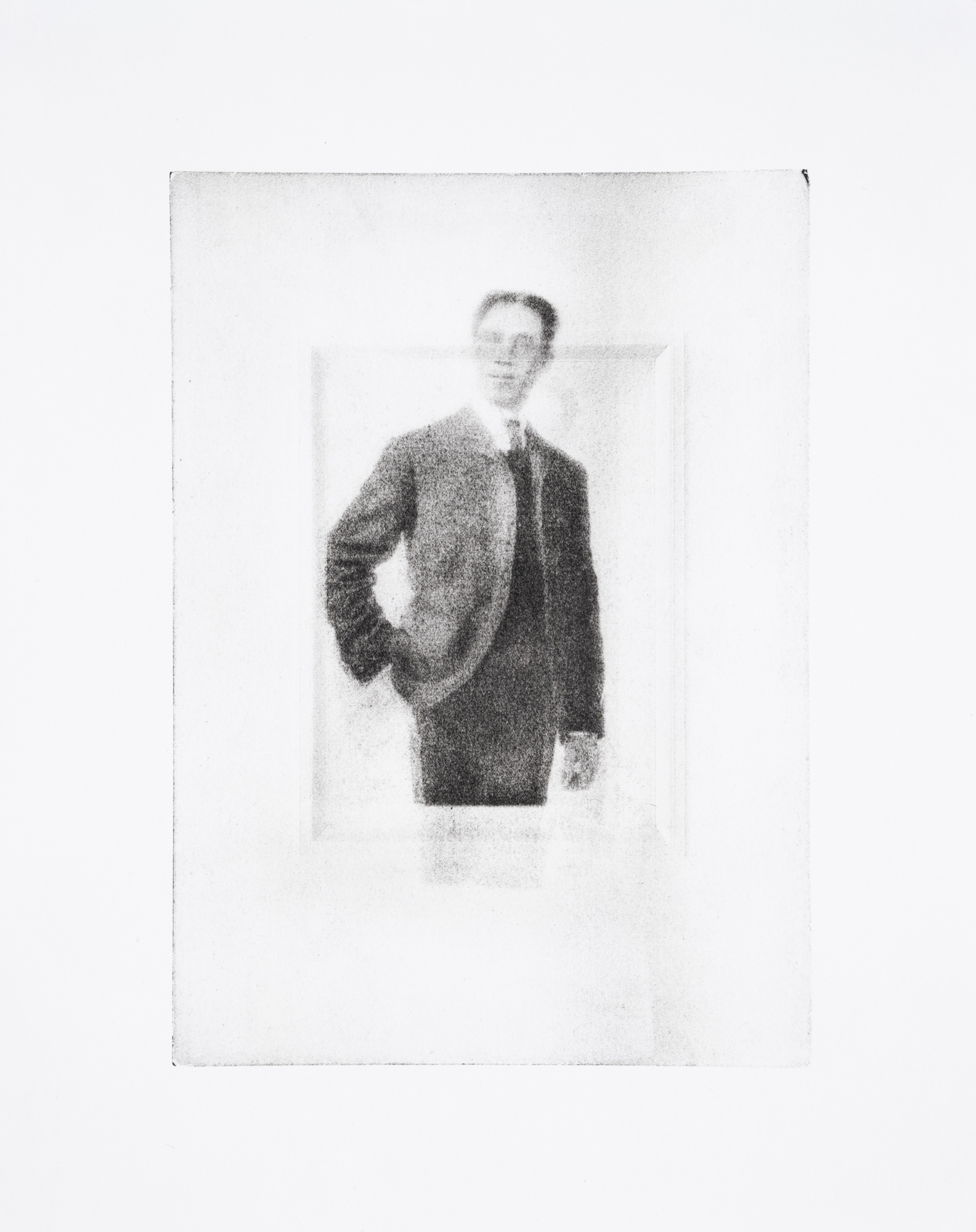

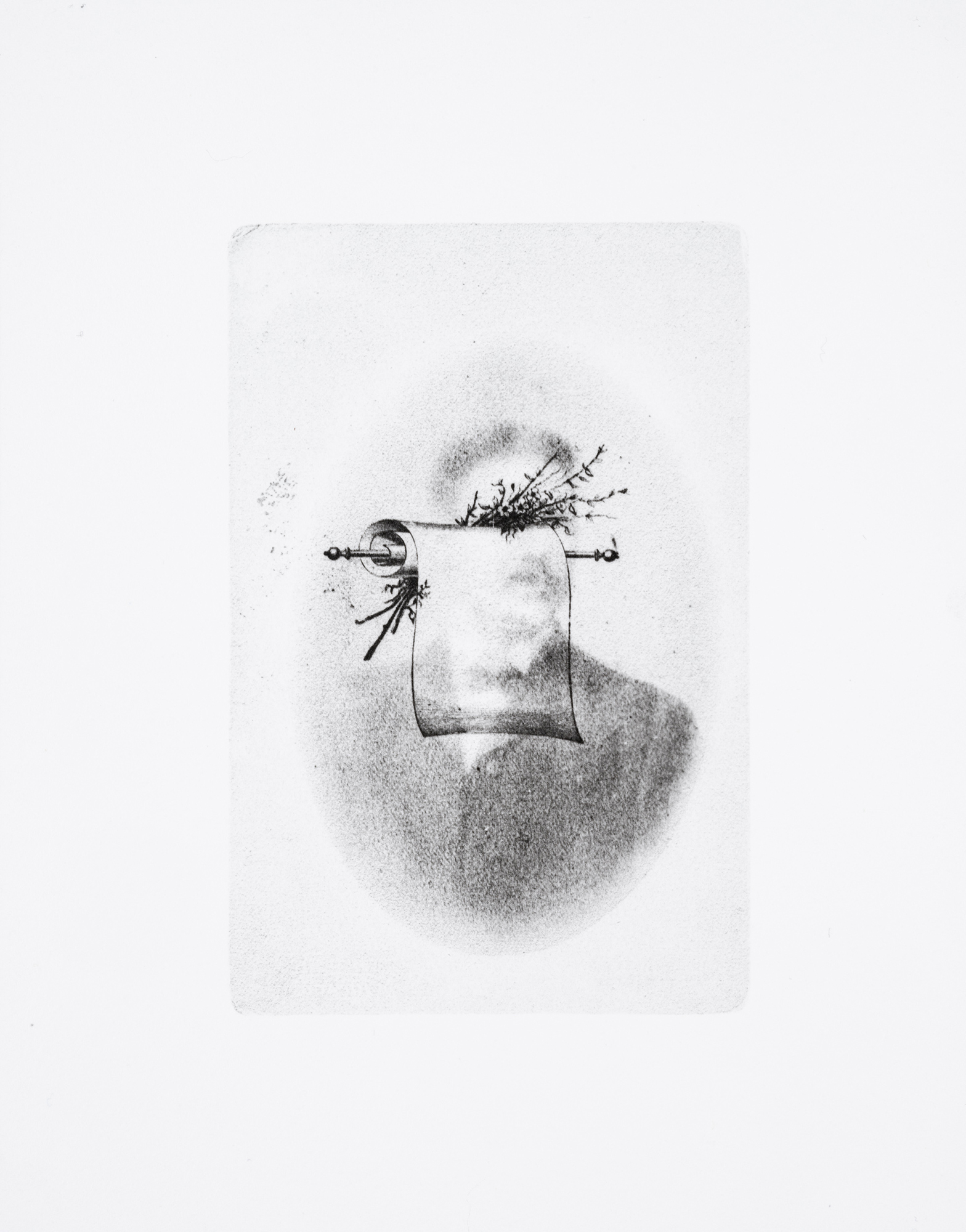

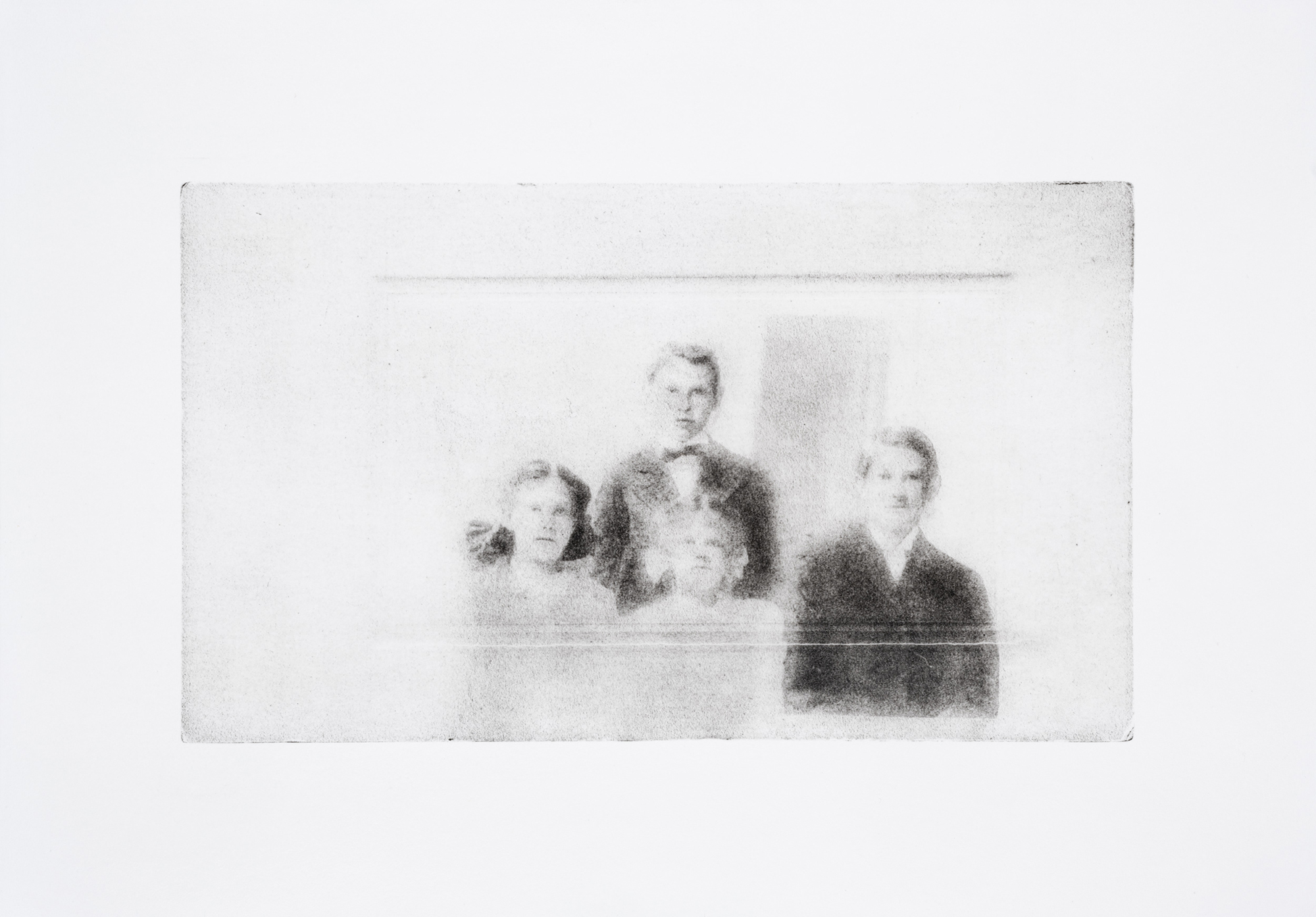

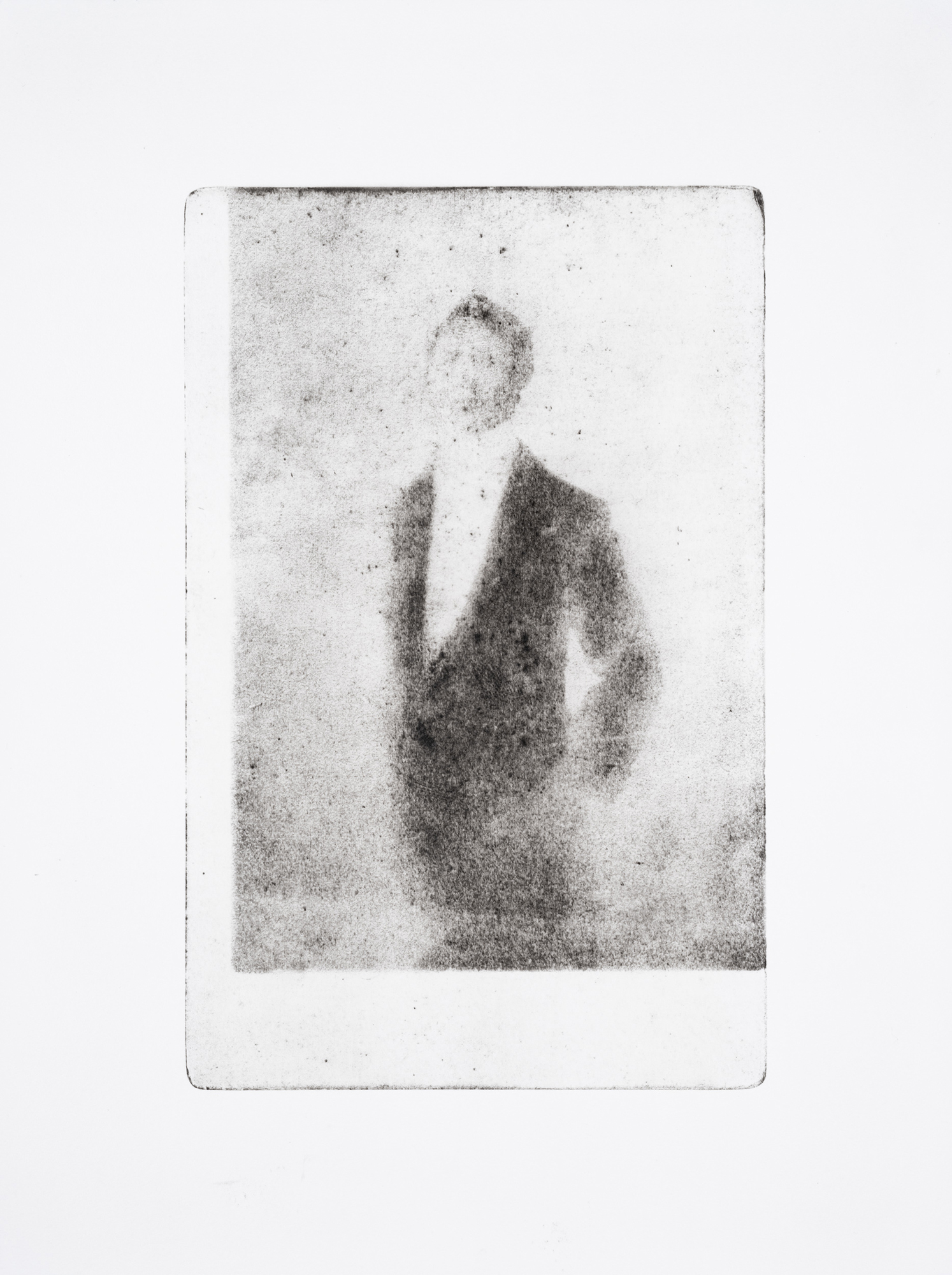

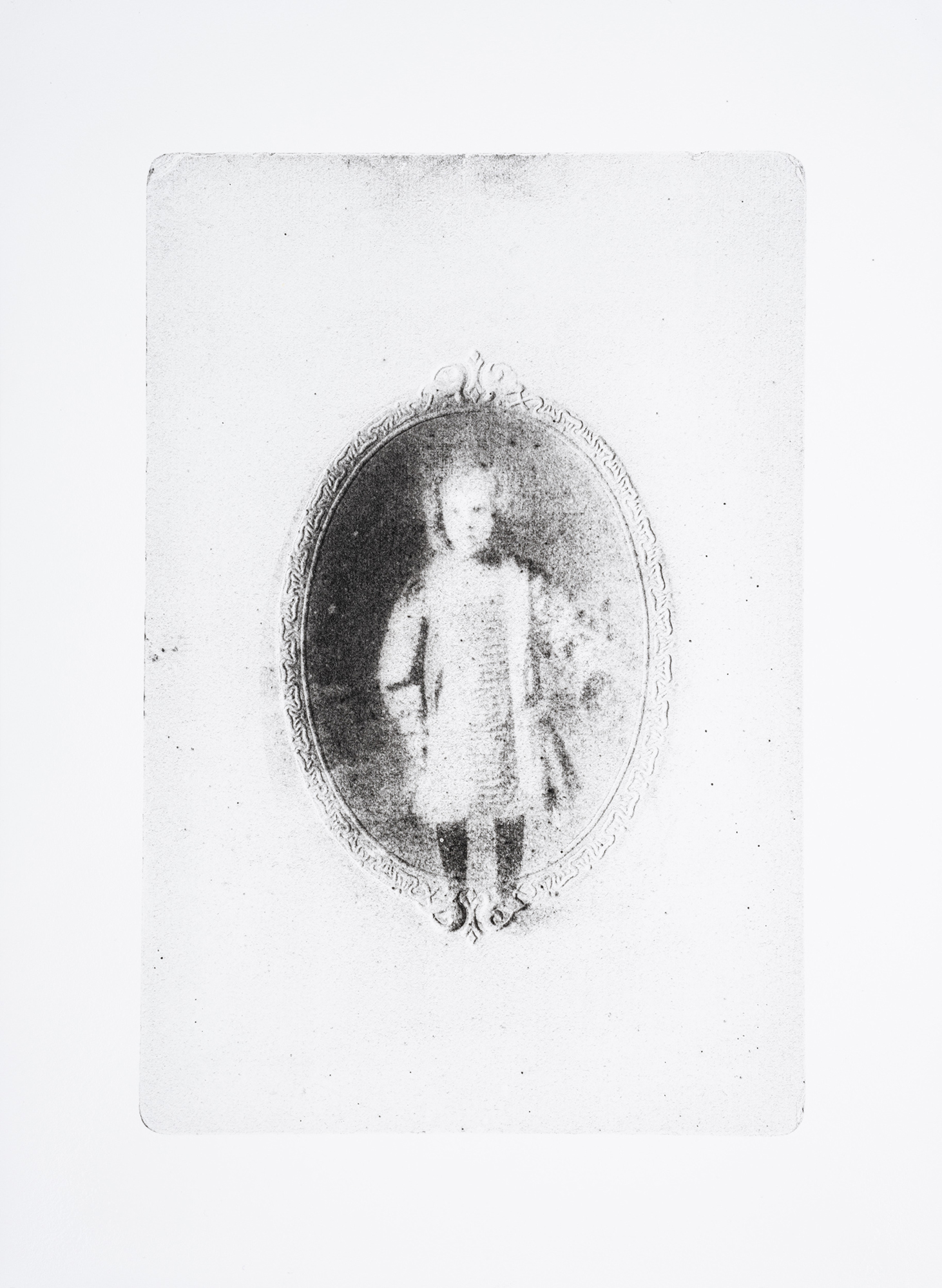

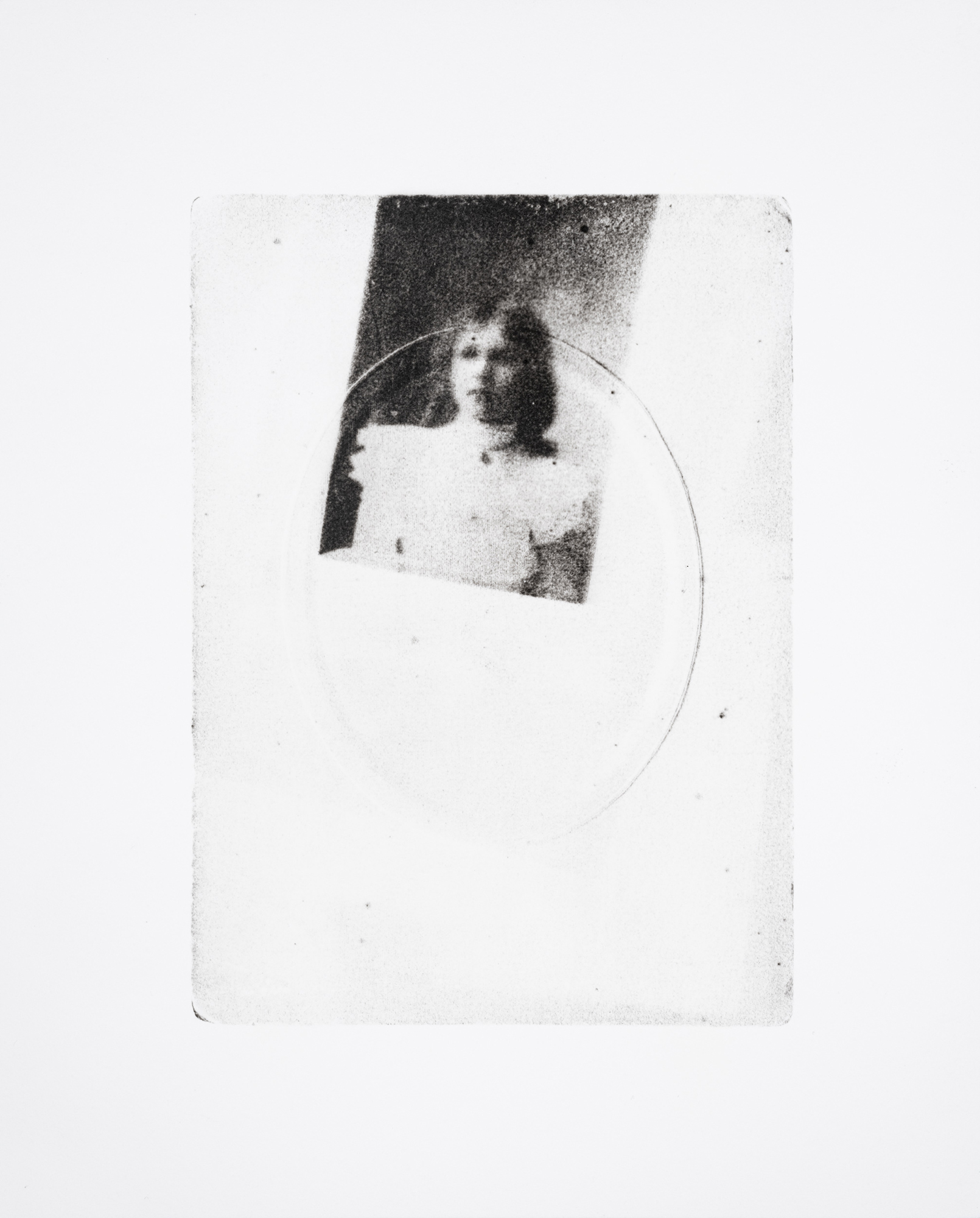

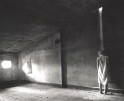

Hiding on the backs of some long-forgotten photographs are “ghost” images, faint traces of other pictures that pressed up against the surface for decades. In fact, these apparitions are a side effect of platinum photography, whose key ingredient reacts with nearby papers, leaving a mirror image. Although platinum photography is revered for its permanence and rich tones, its use declined before WWI because platinum was needed for explosives. This destructive ability is the same power that accidentally produces ghost images. Amazed by this phenomenon, I have been searching the backs of thousands of old pictures for nearly three years, hunting for ghosts. I carefully re-photograph them with a special lighting system, make a new negative, and then a modern platinum print, which reanimates the cycle and provides the ghosts another chance to multiply. This process harnesses their mysterious visual qualities and points to a surprising wrinkle in the fabric of the medium: the photographs are reproducing themselves.

Daniel George: To begin, would you share how Ghost began? How did you learn of “destructive ability” of the materials that make these images?

Andy Mattern: This project began in the best possible way… by accident. I first came across a ghost image while pawing through boxes of old pictures in an antique store in 2021. I was not searching for anything in particular, just curious to look. On that day, there was something surprising on the back of one of the images: a faint trace of another picture. At first, I had no idea how this image came to be. Eventually, I found the some clues in a captivating book, Platinum and Palladium Photography: Technical History, Connoisseurship, and Preservation (2017, edited by Constance McCabe). The research determined that ghost images are the result of a catalytic reaction from platinum in old pictures touching nearby paper. Platinum is a powerful catalyst, it transforms the cellulose in adjacent papers if left in contact for many decades. Notably, platinum as a photographic form fell out of use in the lead up to first world war because the rare metal was required to make explosives. I find that fascinating, that a chemical involved in such a destructive process could also be inadvertently creative.

DG: I’m sure that many of our readers (along with myself) would enjoy hearing more about your process—from finding the ghost images to creating the final platinum prints that we are seeing. Would you mind explaining further?

AM: It took years to find more ghost images, searching the backs of thousands of old photographs in antique malls, secondhand shops, and estate sales, but eventually I amassed a collection. From an artistic standpoint, I wanted to interpret the ghost images, rather than simply displaying the found objects. Through trial and error, I discovered that by lighting them from the side, the otherwise faint images became more visible. I then carefully rephotographed each one in order to make a large digital negative to produce a new platinum print. At this phase, I also adjust the scale of the negative so the figures appear at the same size relative to one another, creating a visual coherence from figure to figure. I had never used the platinum process before, so there was a learning curve. Thankfully, Bostick & Sullivan in Santa Fe still produces all the necessary chemicals, and with some patience, it yields stunning results. The platinum emulsion must be carefully mixed and immediately brushed on non-buffered 100% cotton paper. After it dries, the image is exposed with ultraviolet light, then the print goes through a series of chemical baths to become permanent, and re-imbued with the missing ingredient to theoretically create yet another ghost image.

DG: I’m curious to hear more about the significance of these found portraits. What do you feel they offer in terms of a “surprising wrinkle in the fabric of photographic representation?”

AM: I am blown away by the idea that the photographs themselves are making photographs. Authorship has always been key to photography — what you choose to photograph, how you frame the image, etc. — but in this case, it’s almost like the medium itself has a hand in the creation of a new kind of picture. The researcher Mike Ware has suggested a name for the ghost image process: “autoplatinotype,” as in “auto-portrait” or “self-portrait” plus platinum. The ghost images are a self-portrait of photography. In history of the medium, there are many different processes — some succeeded, while many failed — but here there’s this strange new/old process: an accidental print form, existing between the purposeful and the failed. One of the problems that photography struggles with is its indexical nature, pictures are most often “of” something. The ghost images complicate this certainty. On the one hand, they are recognizable human figures and there once was a photographer involved, however, both the model and the author are now lost and the transformation of the source portrait into a ghost image has changed it forever. Specificity is lost, and we the viewers are left with just a suggestion, or a hint of a person and of a time.

DG: In your photographic work, you often work within processes that, as you state, “dissect the medium itself.” Would you tell us about this broader interest of yours?

AM: The kernel of this direction appeared a couple years after graduate school when I felt compelled to redact the example images and text on photo paper boxes. It started as a kind of visual housecleaning in my tiny studio, feeling the need to block out “uninvited” images and messages. Almost immediately, I found myself re-photographing these redacted packages, recycling them back into photography. Upon reflection, I understood this gesture as a kind of quiet protest against the constant recommendations and expectations of how the medium should be used. Always thinking about the image as an object, I decided to print these photographs one-to-one, reproducing them at life size. Yet, despite this hyperrealism, they quickly become abstract. I love that vibration between the known and the non-yet-known. Seeking other instances of this grey area has remained more interesting to me than making photographs that fall into more traditional categories.

DG: The visual quality of these images is eye-catching, and certainly contains a mysterious component. For me, they provoke more questions than provide answers. What sort of things do they cause you to wonder about?

AM: I find myself searching the faces, the gestures, the attire and imagining these people who are now gone. That often happens when looking at old photographs — we know that these people are no longer with us — but the lack of clarity in the ghost images invites the eye to linger. I think about the desires that we put into our self representations, even today with selfies and social media, and how ultimately it is all temporary. The ghost images are an artifact of the human desire to be seen. We declare: I am here! The beauty of the ghost images is how the medium of photography has nurtured this desire. Even though the source photographs that made the ghosts are now long gone, this new generation remains, and being reanimated with platinum gives them yet another opportunity to reproduce. So there is this chain, connecting the past to the present, pointing to our desire for permanence, yet ultimately it will all disappear.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026