Dana Stirling: why am I sad

In the ongoing evolution of my artistic journey, I find myself engaged in a profound process of self-examination, mental health and sadness – using the camera to explore the essence of who I am and my connection to the art of photography. – Dana Stirling

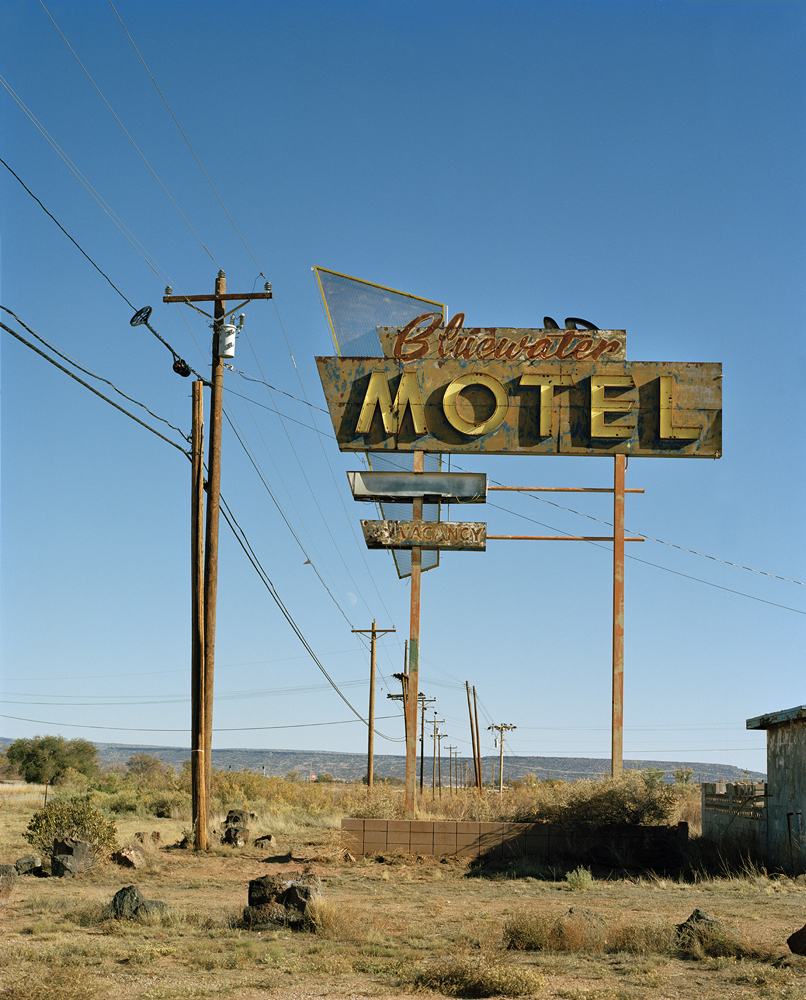

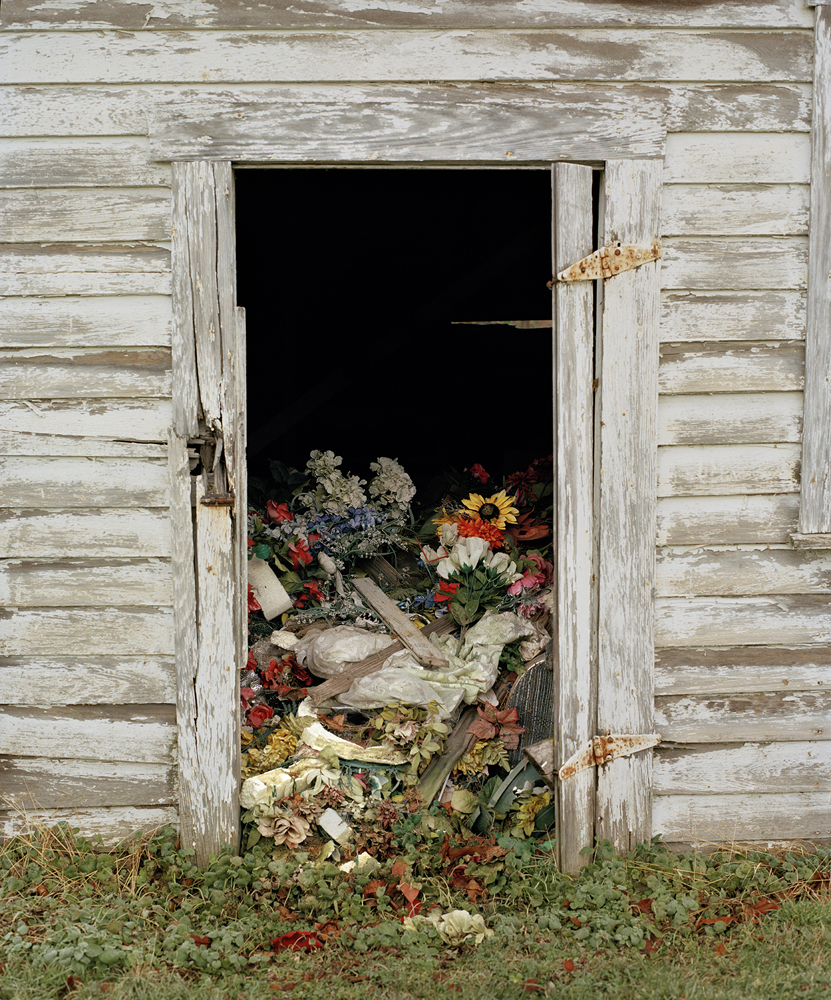

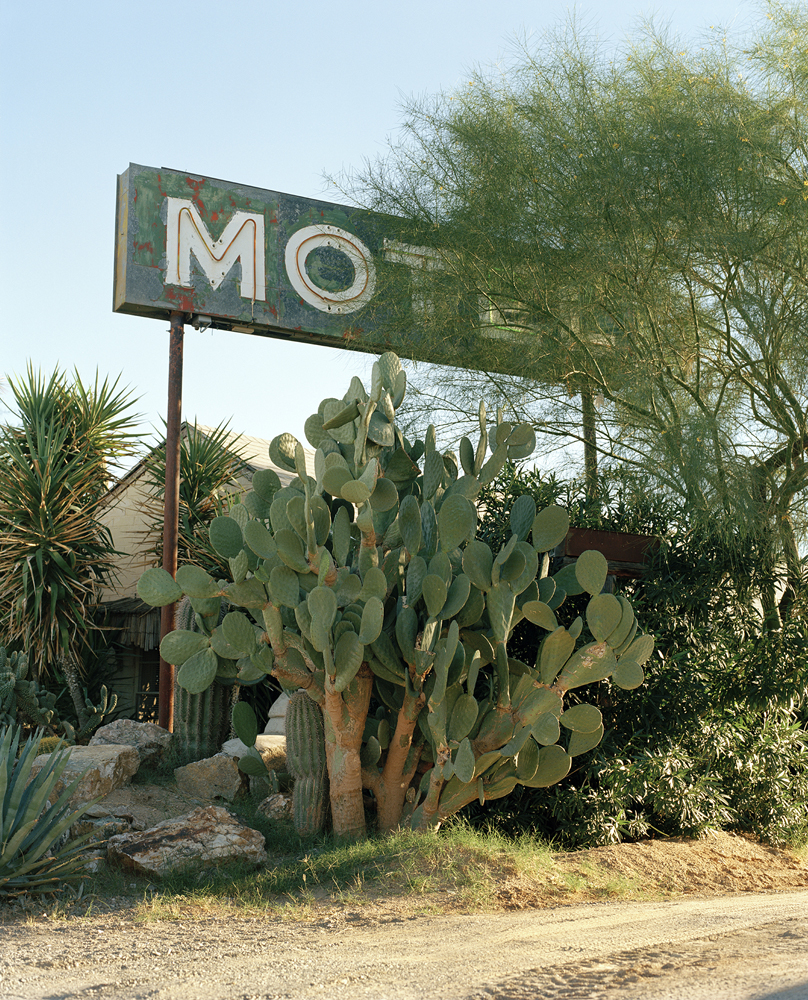

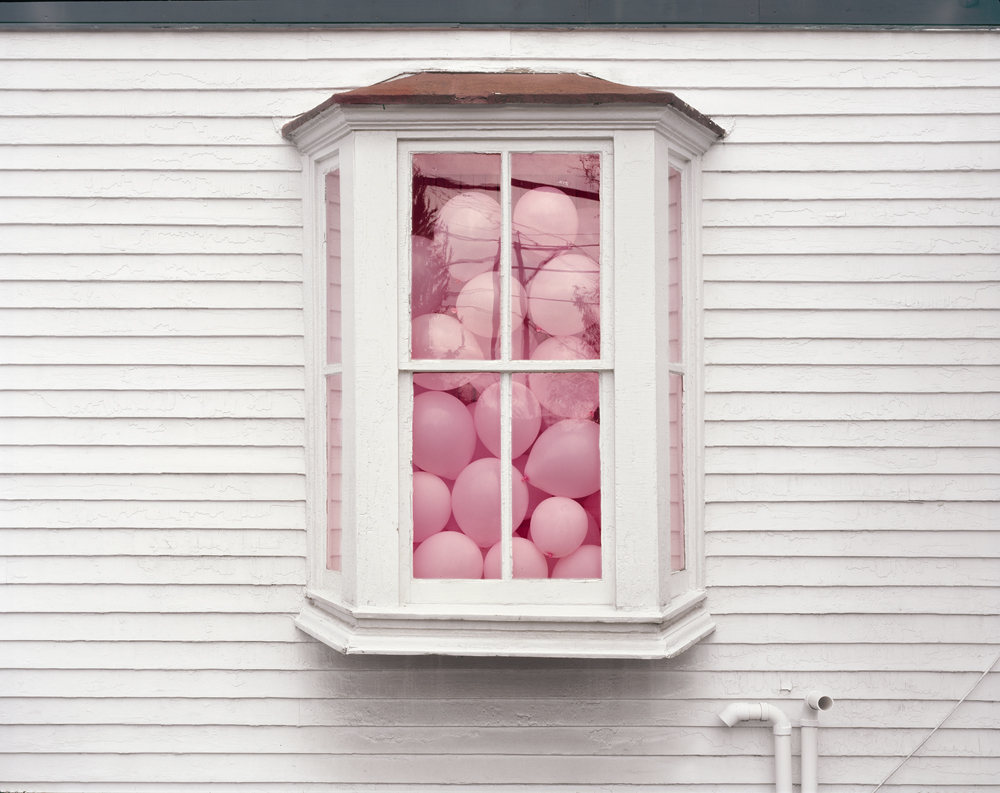

As we enter December Holiday madness, it’s a good time to consider that not everyone is merry. Artist, Editor, and Designer Dana Stirling has just published a monograph, Why Am I Sad, published by Kehrer Verlag, that looks at the world with a rare sense of irony, humor, and sadness through a lens of depression. Her stellar visual consideration of mental health is shared through a series of works that straddle the line of humor and pathos. As Stirling states about the project, “It’s an exploration of how art can both heal and haunt, of how it can serve as both a mirror and a map.”

An interview with the artist follows.

Dana Stirling is a fine art photographer and the Co-Founder & Editor of Float Photo Magazine since 2014. Dana is currently based in Queens, New York. She earned her MFA in Photography, Video, and Related Media from The School Of Visual Arts in 2016, following her earlier BA in Photographic Communications from Hadassah College Jerusalem in 2013.

Dana’s work has been prominently featured in group exhibitions in the United States and internationally, including reputable venues such as Candela Books + Gallery, Panopticon Gallery, William Paterson University, Lafayette College, Colorado Photographic Arts Center, FotoFocus Biennial, Inga Gallery, Tel Hai Museum of Photography, and Saatchi Gallery.

Her photography has gained recognition in various publications, including Buzzfeed, C41 Magazine, Humble Arts Foundation, Musée Magazine, One Twelve Magazine, She Shoots Film Magazine, FishEye Paris, European Photography Magazine, The Week Photo Blog, Feature Shoot, Hyperallergic, PetaPixel, It’s Nice That, Fast Co. Design, Lensculture, Der-Grief Magazine,Lenscratch, The Telegraph Newspaper, and others.

Her hand-made artist book “dear artist : we regret to tell you” is a part of these select library collections, Yale University, Mass Art College of Art and Design collection, Savannah College of Art and Design collection and Goldsmith University, London.

She was awarded the Shutter Hub YEARBOOK Award (2021), NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow Finalist in Photography from The New York Foundation for the Arts (2019), Gross Foundation-Grant for Excellency in photography (2013) and Google Photography Prize, Final Ten at Saatchi Gallery (2012).

Instagram: @dana_stirling

why am i sad

Depression affects nearly 280 million people worldwide. Why Am I Sad is my attempt to make sense of my place among them.

Why am i sad is a deeply personal story and a universal exploration of mental health, self-examination, and the emotional undercurrents of sadness. Using photography as my guide, I delve into the essence of who I am and how my identity is inextricably tied to my art.

I grew up in a small town—a setting that might seem idyllic but often left me feeling profoundly alone. This loneliness was not only rooted in the isolation of my physical surroundings but also within the walls of my home, where silence spoke volumes.

Home, for me, was not a haven. It was a place where the shadows of stress, anxiety, and unspoken sadness loomed large. My mother, silently battling clinical depression, became a figure of profound impact on my emotional world. Her depression wasn’t merely something I observed—it was something I absorbed. Over time, I watched her retreat further into herself, piece by piece becoming someone I no longer recognized, her person dulled by the weight she carried.

As a child, I didn’t fully understand her pain. I only saw my own reflection in her sadness, assuming it was part of an unspoken inheritance. It wasn’t until I grew older that I began to understand how her struggle had shaped my own battle with depression. Her sadness became the backdrop to my life, influencing how I navigated my own emotional landscape.

Photography became my sanctuary in these moments of isolation. In the quiet of my childhood bedroom, I would turn to my camera, finding solace in capturing the mute poetry of objects around me. These everyday items became vessels for my unspoken words.

Through photography, I created a language of my own, one that required no words. Each image held a fragment of the things I couldn’t say aloud, a form of connection that felt less fraught and more forgiving. Objects, unlike people, didn’t judge; they simply bore witness, holding space for my emotions.

Even as I physically distanced myself from that childhood home, the sadness remained a constant companion. What began as a refuge in photography gradually became a paradox: both a lifeline and a weight. On days when I couldn’t bring myself to photograph, I felt lost. Yet on days when I did, my images bore the unmistakable imprint of the sadness that had shaped me.

Why Am I Sad is an open-ended question, a journey into the heart of my relationship with photography. It’s not about seeking a definitive answer but about holding space for the question itself. It’s an exploration of how art can both heal and haunt, of how it can serve as both a mirror and a map.

Congratulations on the book, Dana! Let’s start at the beginning and tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography…

When I was younger, I was always envious of my sister and grandfather—they were both so naturally gifted at drawing. I desperately wanted to be creative, but drawing just wasn’t in my genes. For a while, I thought maybe I could be a writer, but if I’m being honest, I’m pretty terrible at it, especially when it comes to anything creative.

In high school, everything shifted when I got a small digital pocket camera. I started using it constantly and fell in love with the feeling of capturing images. I took photos around the house, exploring whatever caught my eye. Later, I got a small DSLR, and my now-husband, Yoav, taught me the basics—aperture, exposure, and how to handle the camera. As I began taking more photos, something clicked. I realized this could be the creative outlet I’d been searching for all those years.

I spent a lot of time alone in my room, surrounded by random objects—egg shells, glass figurines, fruit, dead bugs, little things that were easy to photograph in a small, makeshift setup. These quiet, intimate moments with these objects behind my closed bedroom door felt personal and meaningful. They became my way of connecting with something outside of myself, even when I couldn’t find the words to do so.

When I went to undergraduate school, everything started to make sense. I began analyzing what I was doing and understanding the deeper connections behind my work. That’s when I truly fell in love with photography—not just as a medium, but with still life in particular. For the first time, I felt like I had a voice, like I could communicate through these images in a way I never could with words.

Finding this form of expression so early in my creative journey allowed me to grow as an artist and explore these ideas in ways I never thought possible. Photography, especially still life, became more than just an outlet—it became my language, my way of telling stories, and the thing that made everything finally feel “right.”

Thank you for speaking so openly about depression. I think it’s so important that we share the difficult part of life and destigmatize it. Were you uncomfortable sharing your feelings publicly?

Absolutely. We often try to present the best version of ourselves to the world, especially on social media, where it can feel like we’re gladiators in a coliseum, battling for the validation of being seen as successful artists (can you tell I just saw the movie?). But beneath the polished posts and curated feeds, there’s a reality we rarely show—a messier, more vulnerable side of the creative process.

For me, the first time I cracked open that polished surface was with my rejection letter book. Ironically, it’s probably my most successful project to date. In that work, I wanted to shine a light on rejection—not just the act of being told “no,” but the weighty, universal feelings of failure and self-doubt that come with it. These are emotions we often hide, out of shame, as if they make us less worthy. By sharing my rejections, I hoped to normalize them, to say, “This happens to all of us, and it’s okay.”

But sharing rejection and sharing depression—those are two very different beasts. When I started opening up about my struggles with depression, it felt infinitely more personal, raw, and risky. Unlike rejection, which could be reframed as a badge of resilience, depression felt like a mark against me. It’s so heavily stigmatized, so often misunderstood, that I worried it would make me seem “less than”—less professional, less capable, less valid. Like a scarlet letter sewn into my identity.

Depression has always been intertwined with my work because it’s intertwined with who I am. My mother’s lifelong battle with clinical depression shaped me in profound ways, leaving an indelible imprint on my own mental health and, by extension, my art. For years, I felt like my sadness “tainted” my work, a shadow over everything I created. When I finally decided to share this part of myself, I was terrified—not just of how the art world would perceive me, but of how my family would feel, and whether it would change the way people saw me entirely.

What I didn’t expect was how deeply this openness would resonate with others. Since releasing my book and sharing my story, I’ve been overwhelmed by the responses—stories, reflections, and connections from people who’ve faced their own struggles with mental health. It’s been a revelation, and it’s shown me just how universal these feelings are, especially within creative communities.

Depression isn’t a weakness, and neither is talking about it. The more we share, the more we realize we’re not alone. If millions of people are struggling, then there are millions of stories waiting to be told—stories that matter. This book is just one of those stories, but it’s a step toward opening the door for more conversations, free of shame, free of guilt.

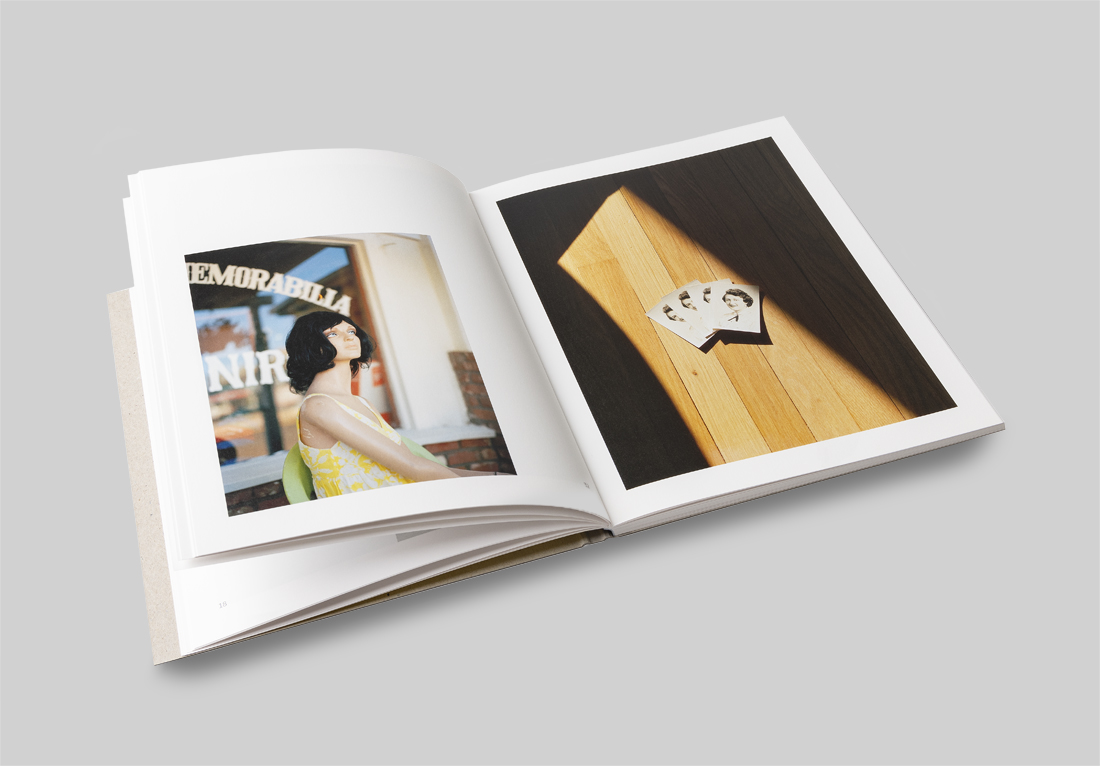

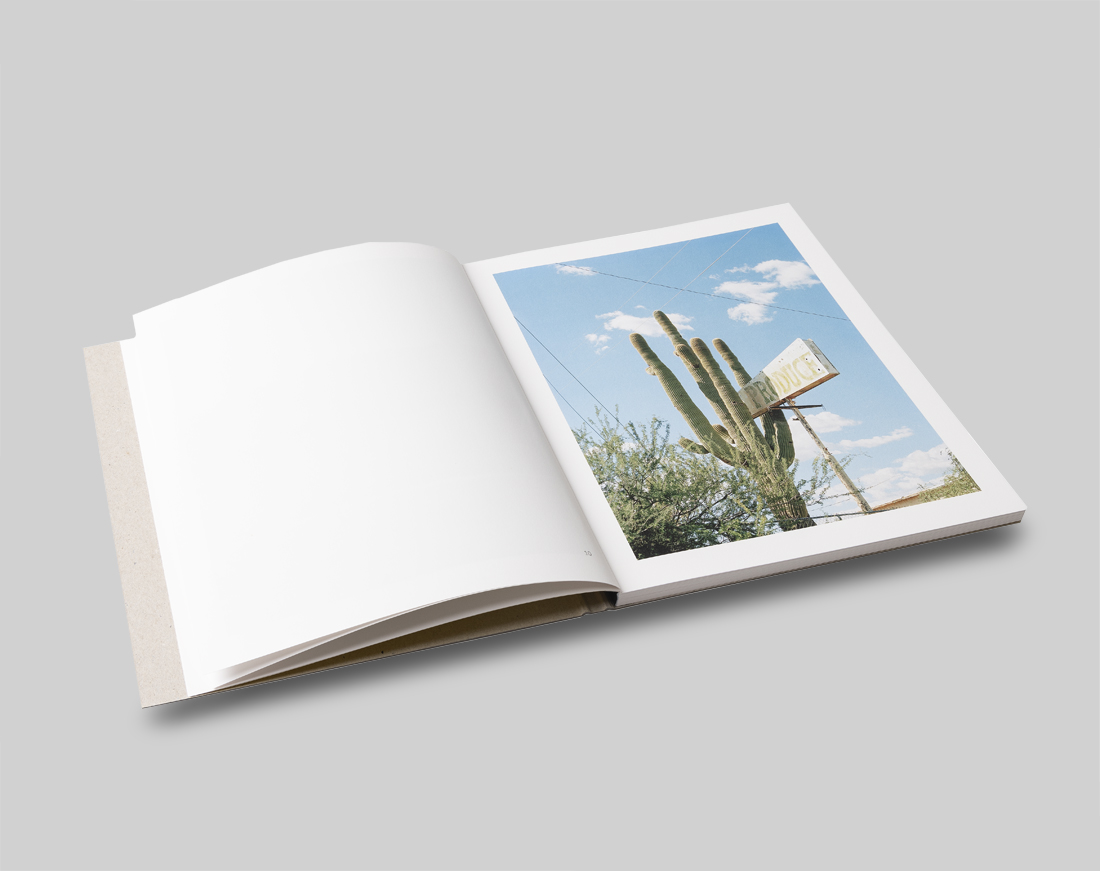

The photography in the book straddles humor and sadness so beautifully. What draws you to making an image?

Thank you—that balance between humor and sadness is something I think about a lot. For me, photography has always been a way to explore the contradictions of life—the moments that feel both heavy and light, beautiful and strange, heartbreaking and absurd. What draws me to making an image is often this tension, this idea that an image can hold multiple truths at once.

I’m particularly drawn to scenes or objects that feel like they carry a story, even if it’s ambiguous or incomplete. I love working with elements that evoke a sense of nostalgia or emotional weight, but I also try to leave room for humor or playfulness. It’s not so much about making a viewer laugh, but about finding the irony in sadness or the absurdity in a somber moment. I think those contradictions make the work feel more human, more alive.

Ultimately, I’m drawn to making images that feel honest—not in a literal or documentary sense, but in the way they reflect my own complicated feelings. I think life is rarely just one thing. Even in our darkest moments, there’s often a strange beauty or humor lurking at the edges. That’s what I’m chasing in my work—the emotional layers that make us who we are.

I often gravitate toward things that spark something in me—moments or objects that allow me to tell a story without words. It’s usually a very organic process, driven by traveling and discovering these little “gems” along the way.

Did anything surprising come out of the making of this book?

You know, not really—I think in many ways I was ready for it. I’ve loved photography books for years; they’ve always felt so special and unique to me. It’s been a long-standing dream to see a book of my own on someone’s shelf. So when the time came, I just went for it. I made an effort to be as prepared as possible, both mentally and financially, which helped make the process feel clear and honest.

That said, the financial realities of producing a book were more challenging than I’d anticipated. But in terms of the creative process, it felt very natural, almost like a culmination of everything I’d been working toward.

What truly surprised me, though, was the response once the book came out. The support and generosity from the photography community have been overwhelming in the best way. I wasn’t expecting such an outpouring of encouragement and connection, and it’s something I’m deeply grateful for. It’s been such a rewarding surprise to see how the work resonates with others.

Did you design the book?

The book is a testament to the power of collaboration and how truly great things can emerge when creative minds come together. I had the immense privilege of working with my project manager, Sylvia Ballhause, and the designer Nicole Gehlen. Their insights, combined with my husband Yoav Friedlander’s thoughtful input, made the entire process a dynamic and rewarding exchange. The back-and-forth of moving elements around, discussing ideas, making changes, and refining the design was a collaborative dance that brought the book to life in ways I couldn’t have achieved alone. I’m deeply grateful for their expertise, support, and dedication to making this work the best it could be.

What are you working on next?

Right now, my focus is on bringing this book and project to as many people as possible because I deeply believe in the importance of discussing mental health in the art world. It’s a conversation that matters, and I’m committed to sharing this work, talking about it, and allowing it to take on a life of its own out in the world.

For me, Why Am I Sad isn’t over. While the book has been published, I don’t see it as a finished chapter. This project feels ongoing—there’s still so much to explore, both within myself and through photography. I want to continue working in the spirit of this book, delving deeper into the themes of mental health, my family, and my relationship with my mother.

Looking ahead, I hope to create more books and projects that expand on these ideas. I’m especially interested in working with found footage and archives, exploring how personal and collective memory shape identity. Above all, I hope to continue making photography that resonates with people and invites meaningful conversations. This is just the beginning.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Andrew Waits : The Middle DistanceDecember 20th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Eli Durst: The Children’s MelodyDecember 15th, 2025

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025