Sylvia Sanchez: Out of the Ordinary

I first met Sylvia Sanchez back in 2012 when I studied at the Panamericana School of Art in Sao Paulo, and she was my teacher in the first year. Demanding and detail-oriented, she showed me from the very beginning the importance of being meticulous in our work and persistent in our research. Her work is intriguing and her tireless dedication to contemporary art is truly admirable. She is also the sweetest person I have ever met. Today we will get to know a little bit of this amazing person through a short interview and couple of her photographic series.

Sylvia Sanchez is a Brazilian visual artist, cinematographer, and educator. Her artistic practice experiments with staged photography, text, and video art/ experimental cinema. Her work is based on the body, on everyday objects and gestures, and on a certain dialogue with the absurd. She discusses contemporary life oppressions, manifested as surveillance/control and as an imperative for productivity, consumption, and conformity to standards. She held her first solo exhibition in 2019 at MIS-SP. In 2020, she took part in “Meios e Processos”, a mentorship program held by FAMA Museu (Itu). In 2022, she was part of the collective exhibition “Latinas”, at Galeria 59 Rue Rivoli (Paris) and created, with Marta Pinheiro, the residency-work Impactos de Convivência, commissioned by Sesc Santana (SP).

IG : @_sylviasanchez_

My artistic investigations radiate from staged photography, text and video art/ experimental cinema, in a practice that has as its central elements the body, everyday objects and gestures and a certain dialogue with the absurd/magical realism.

I explore issues related to surveillance/control/power and the imperative of productivity, consumption and alignment to standards. These are daily fife oppressions which, since being so close and usual, are often naturalized and unnoticed. I am interested in inviting the public to step outside the automated flows of everyday life and into the surprise and criticism that can arise from the strangeness provoked by displacements of common and extremely familiar elements – whether through poetry or humor.

I look at the apparently banal entrails of everyday life because, for me, it is there where the structural relations of power, as well as social, cultural and political domination, all part of a system that works to transform people into numbers, machines, an army, are reproduced.

This reproduction shows of in the gestures made to belong, to assert oneself, to have fun or to survive. It shows of in the (more or less conscious) decisions about where to invest time and money. It shows of in the consumed and circulated information.

But I believe this ordinary triviality, for being so familiar – and therefore charged with affection – also harbors great potential for restituting humanity – through the recovery of attention, critical thinking and poetic imagination. This is the path I seek to follow in my artistic works. Hence the central place that the body, everyday objects and gestures and the dialogue with magical realism occupy in my research.

Since the pandemic, I have begun to direct my explorations towards the universe of mobile and online technology. Since last year, specifically, I have focused on our relationship with the “Big Techs”: a daily, intense, intimate, very non-transparent and completely asymmetrical relationship in terms of power (in addition to being ecologically harmful). A relationship that undoubtedly offers comforts and pleasures, but in return, demands very high (and often ignored) “tolls”.

I have been delving into issues related to computational visibility: the transformation of individuals into extremely visible objects, via an immense mass of data and images that are invisible to the human eye and assimilation, and readable only by machines. Every time one is online, their data is captured. Thus, being connected to the internet is becoming visible. And becoming visible is being more at the mercy of control.

More than 20 years ago, before starting my artistic career, I worked at a direct marketing agency, where I had my first contact with data mining – at a time when people still did not carry the internet in their pockets and when data collection and analysis tools were still relatively rudimentary. What initially fascinated me due to the possibilities it opened up for understanding (and influencing) behaviors, soon became the target of my ethical questions. Today, it is a fundamental subject in my political and emotional concerns – and, therefore, central to my artistic production. – Sylvia Sanchez

Crônica de Banalidades Ordinárias (2018) – Chronicle of Ordinary Banality

Chronicle of Ordinary Banality invites reflection on the notion of normality. Could the so-called “normal” be nothing more than a set of situations we’ve learned to interpret? Situations typically chosen for their functionality, allowing them to fit seamlessly into the productive flow of daily life. Among these choices, there exist a multitude of occurrences which, if isolated, would be deemed strange—yet they are as close and recurrent as what we call “normal.”

To bring this proposition to life, two seemingly opposing realms—absurdity and the everyday—are juxtaposed in scenes performed for the camera. These scenes take place in familiar domestic spaces, populated by mundane objects out of context and crossed by gestures stripped of their usual functionality. Gestures that belong to ordinary life but subvert its logic and purpose; gestures that stretch the boundaries of the habitual, suggesting fantastic narratives while retaining a whiff of the familiar.

These scenes freeze fragments of absurdity that dwell within ordinary events, often overlooked. They echo a peculiar, expressionless humor—a quiet bewilderment, as if recognizing that the strange also reflects oneself. In the usual practices and interests ascribed to photography, they are anti-photographic (they oppose the “decisive moment”; they oppose the “memorable” or “Instagrammable” moment). They confront and challenge the legitimacy of behavioral conventions dictated by a society obsessed with productivity and validation.

What led you to work with photography and most recently cinema? And what are the main differences between them?

I began photographing during my studies in Social Communication as part of one of the course’s disciplines. I quickly realized that this practice placed me in a state of presence that deeply nourished me. Photography invited me to observe my surroundings with greater curiosity and served as a pretext for exploring new spaces, objects, people—and new ways of relating to them.

As soon as I started studying photography more seriously, I realized I was more interested in constructed or staged photography than in street photography. My creative expression has always been rooted in imagery, which has constantly proliferated in my imagination—and photography proved to be an effective way to bring these images into the world.

I have always been deeply connected to theater—with its physical play and storytelling—and to literature, particularly magical realism. As my practice evolved, I recognized that my interest in constructed photography stemmed from these influences: my desire was to create fantastical visual narratives.

I understood that bringing together images, the body, storytelling, and “the improbable” was what truly captivated me in my artistic exploration.

From there, moving images became a natural extension of my work with still photography, depending on the needs of each idea or project.

The key difference I see between still photography and audiovisual work is the notion of the “instant” that photography holds versus the “unfolding over time” inherent in cinema. While photography captures a single moment, audiovisual work deals with the continuous “becoming.” I find it wonderful to navigate between both worlds.

What motivates you to start a new project?

I start a new project when something begins to “scream” inside me, relentlessly pursuing me. It could be a mundane subject, a specific situation, a philosophical restlessness, or even a person. This “internal scream” sometimes points to a need for research, prompting me to delve deeper into the topic. Other times, it emerges as an image or as a desire to place a body—my own or someone else’s—in certain gestures, places, or situations, often improbable ones.

Tell us about the relation you see between photography, text and cinema.

I believe my practice is always rooted in imagery—whether presented as a static or moving image or as text. I am not an artist focused on temporal narratives or plot; I am drawn to synthesis (metaphor, paradox) and the connections between them.

In this sense, I approach text in a “photographic” way: I appreciate the power of short phrases (akin to the photographic instant) and aim to craft written language in a way that evokes images—or that intrigues and/or confuses.

Regarding audiovisual work, what interests me is the “physical” presence of elapsed time and the possibility of weaving connections within a single piece. I think of audiovisual work more as a moving photobook, offering a broader range of expressive tools than a traditional photobook.

What are the biggest challenges you face?

Since I work in multiple areas—authorial production, guiding creative processes, and more commercial audiovisual production—I sometimes find it challenging to dive deeply into everything that interests me to reach the levels of excellence I aspire to.

This becomes even more challenging because I usually work on several projects simultaneously, and I’m also extremely curious about new ideas—I enjoy experimenting with new languages and technologies. The desire to delve deeply into everything is immense, but the time to do so never is. That is the greatest challenge of all.

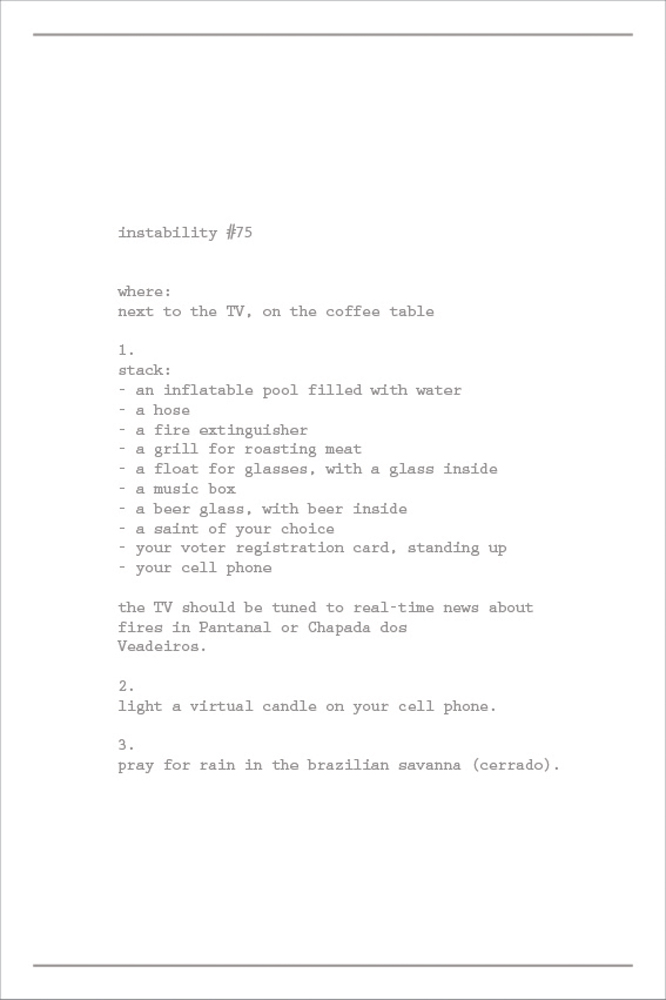

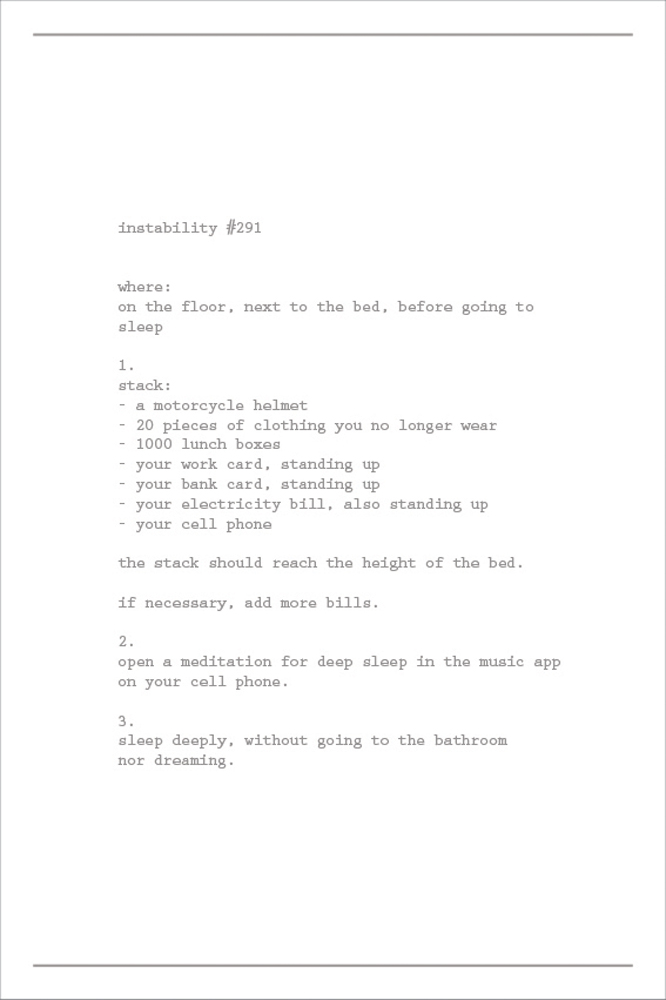

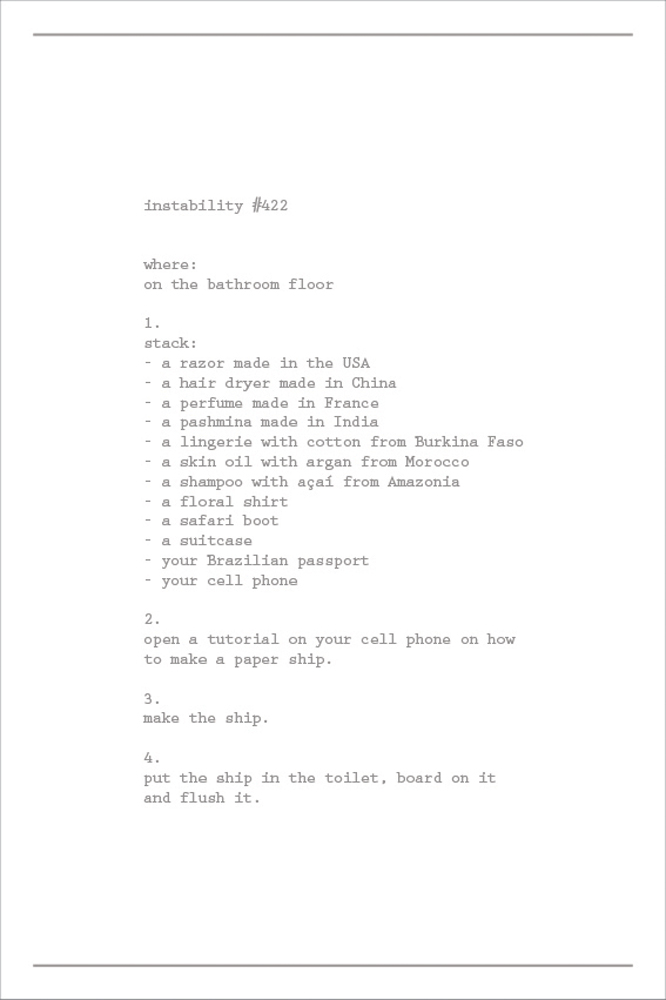

Equilíbrio Instável (2020-2022) Unstable Balance

Unstable Balance is an installation composed of photographs and performative programs revolving around a rather mundane task: using everyday objects to create stacks that can hold a mobile phone in various domestic settings, reflecting its growing omnipresence in the 24/7 capitalism of modern life.

The photographs showcase stacks that present themselves as plausible structures, yet carry an element of improbability. Despite fulfilling their purpose, they do so inadequately; their very structure embodies a fragile equilibrium on the verge of collapse—mirroring the precarious state of contemporary political, economic, social, and environmental systems, as well as the daily life of individuals striving to maintain balance amid infinite urgencies and constraints. These stacks are “makeshift sculptures,” simultaneously totems of uncertainty and small altars to technology, within which the only human presence appears, dwarfed and insignificant.

The instructions, in turn, propose stacks whose balance is clearly impossible. They conclude with actions that extend beyond stacking—actions that expand the human and political dimension of the textual propositions and invite the viewer’s active engagement. They prompt the body, physically or imaginatively, to break free from the almost-falling passivity of the mobile device—a device that both burdens and anesthetizes.

Both the images and the instructions carry a certain humor tinged with discomfort. Together, they create a dynamic in which the tangible and the imaginary complement each other as possibilities. And in this interplay, they pose a challenge: how do we keep from collapsing?

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025