J.A. Young: Of Fire, Far Shining

For the next few days, we are continuing to look at the work of artists who submitted projects to our most recent call-for-submission. Today, we have Of Fire, Far Shining by J.A. Young.

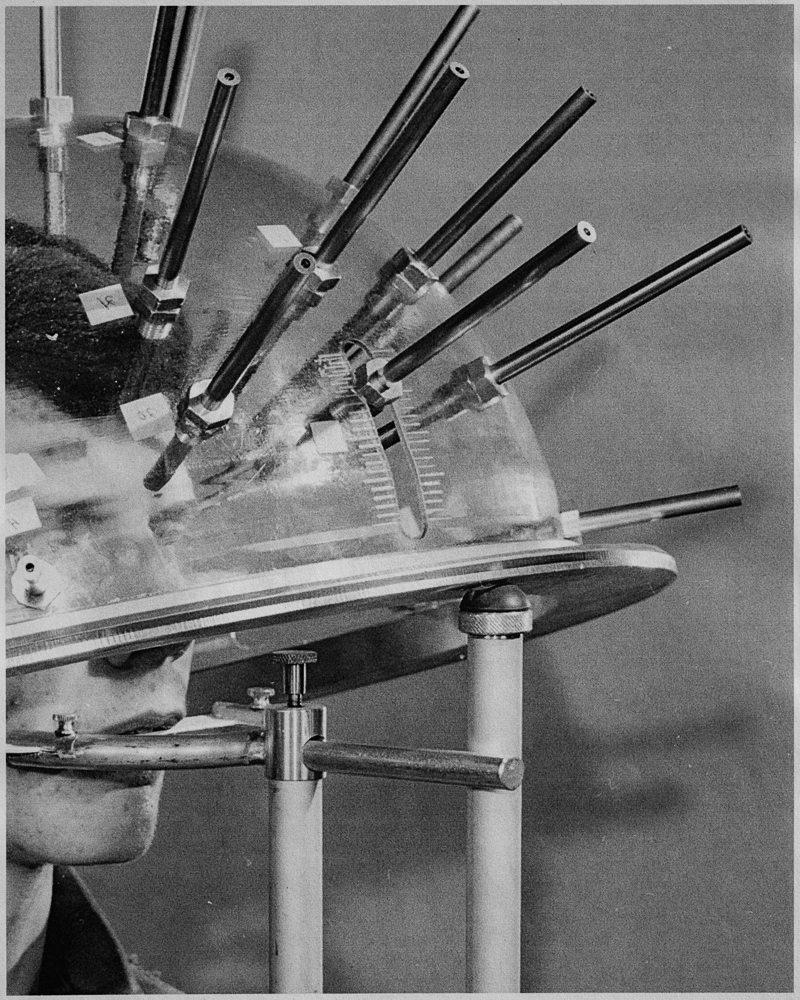

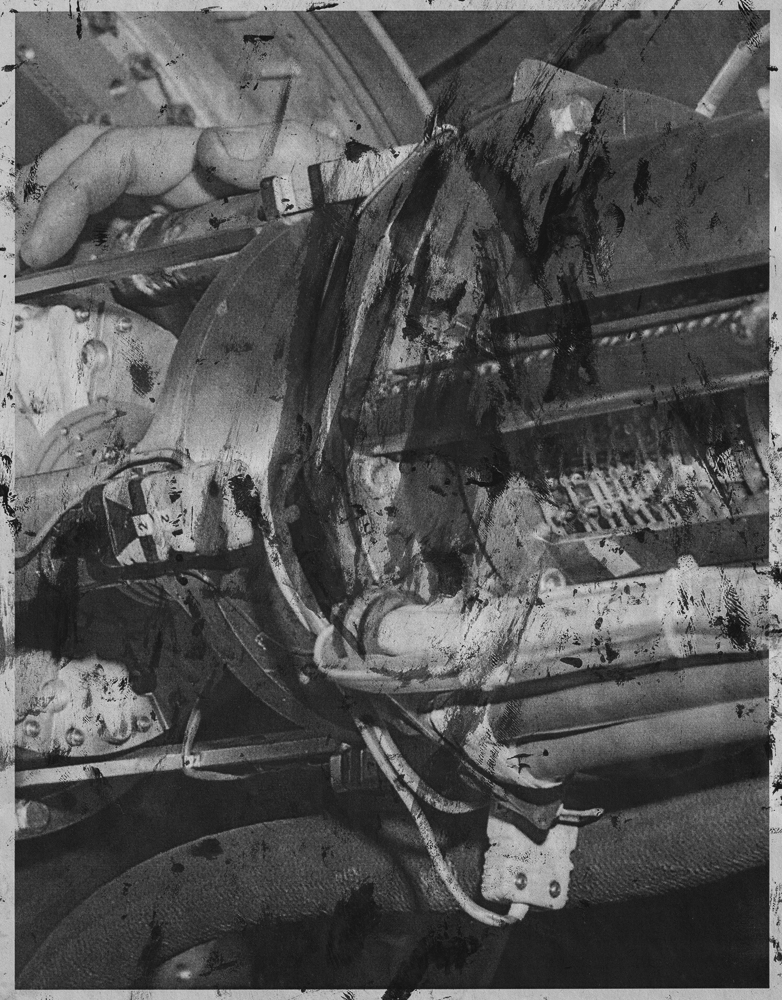

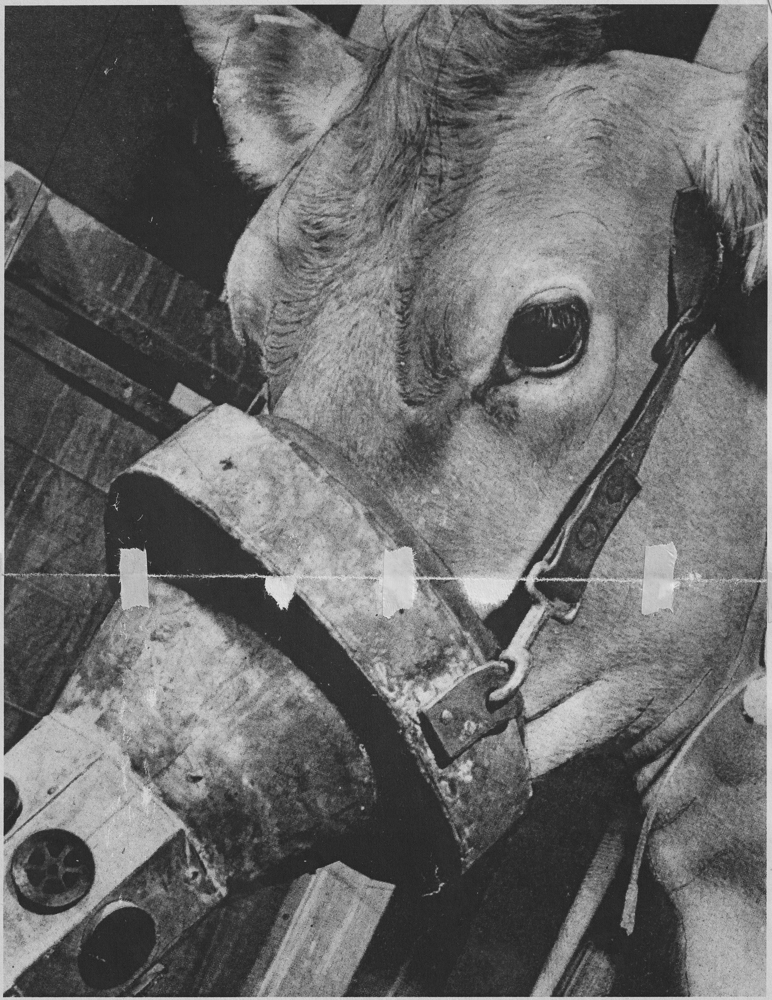

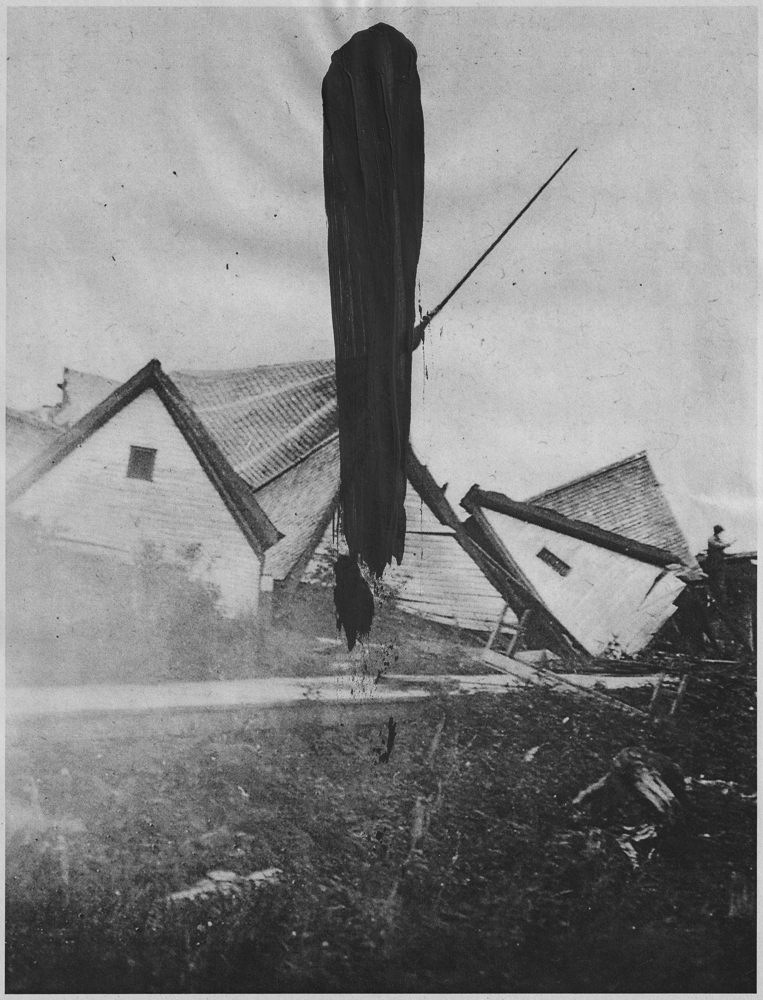

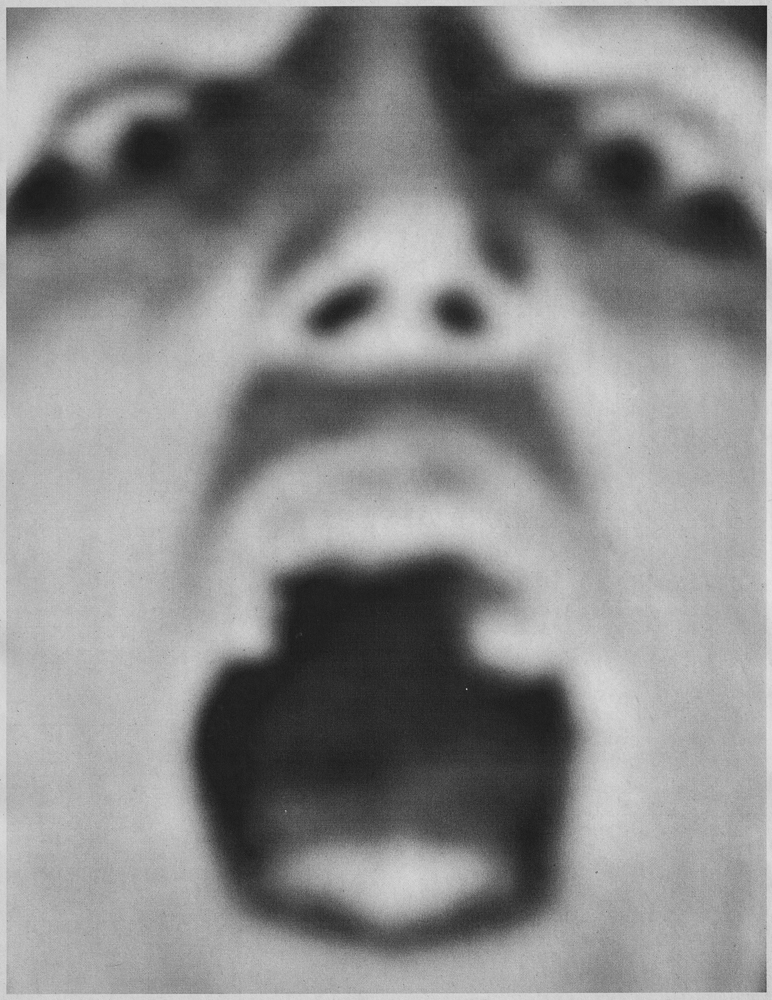

J.A. Young (b. 1986) is a queer photographer / multi-media artist based in the American South. Her work draws on a range of influences, including cultural anthropology, world mysticism, the occult, and paranormal phenomena. Using both personal photographs and public domain archival images as raw materials, Young employs various methods (e.g., dramatic recomposition, spontaneous print manipulation, darkroom experimentation, and rephotography) to transform subtle feelings into tangible visual expressions.

Follow J.A. on Instagram: @_ja_youn_g

Of Fire, Far Shining

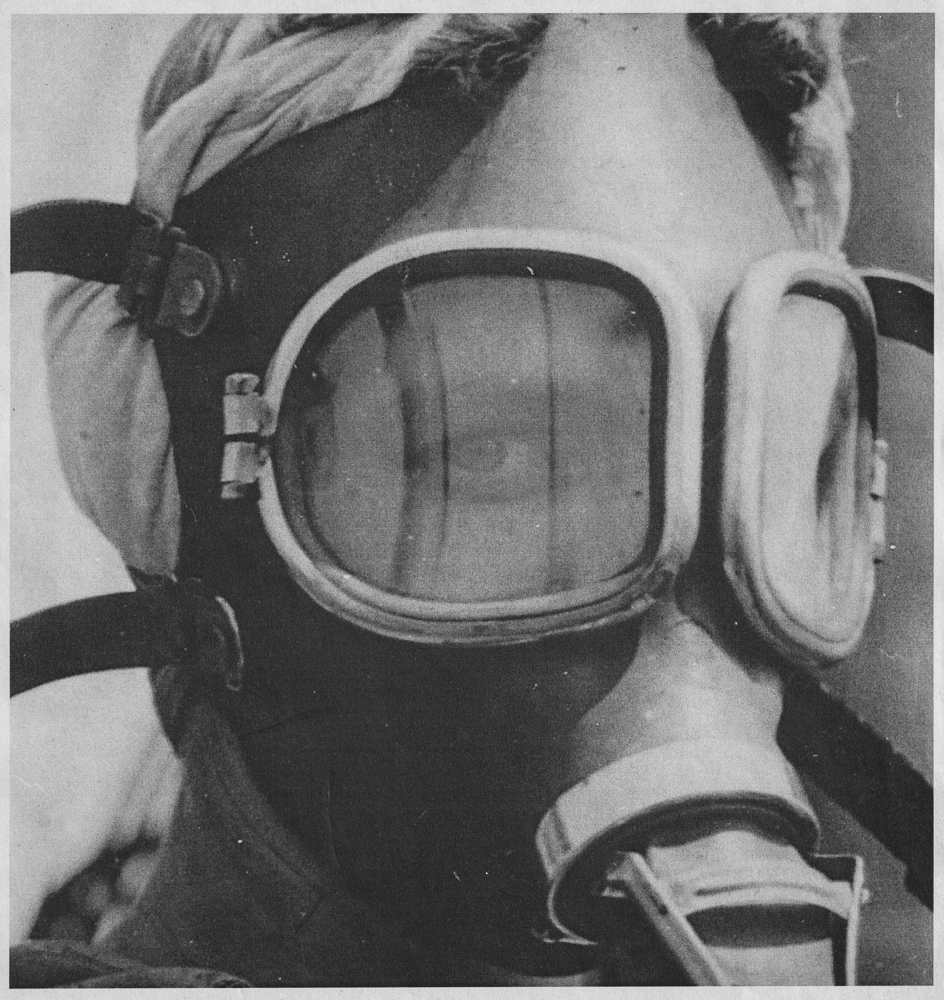

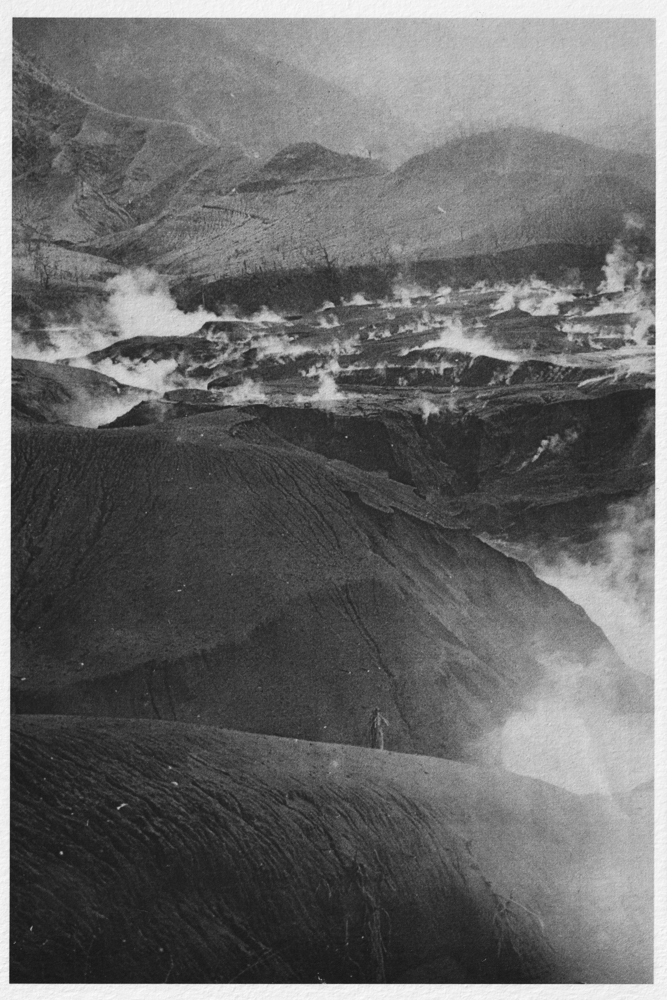

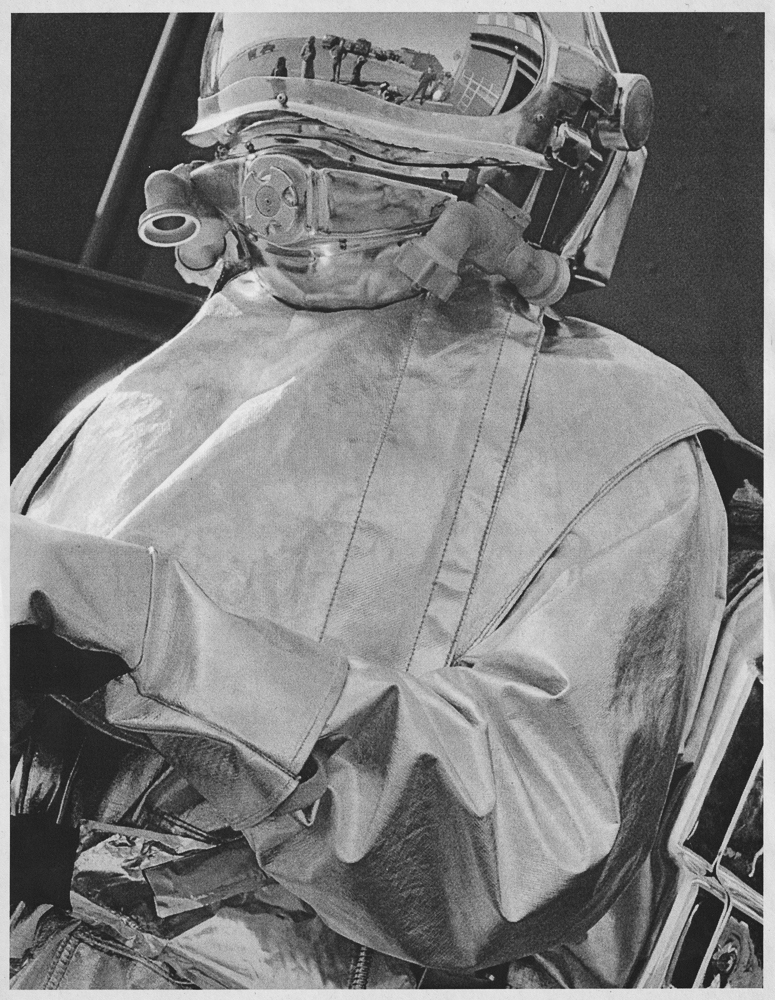

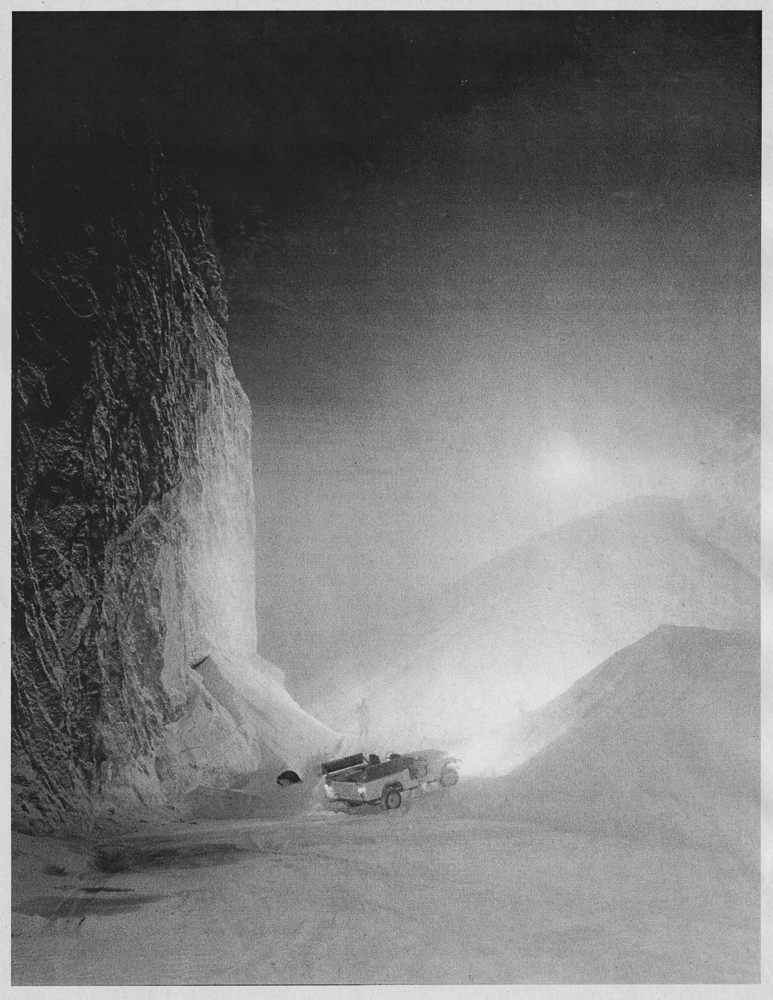

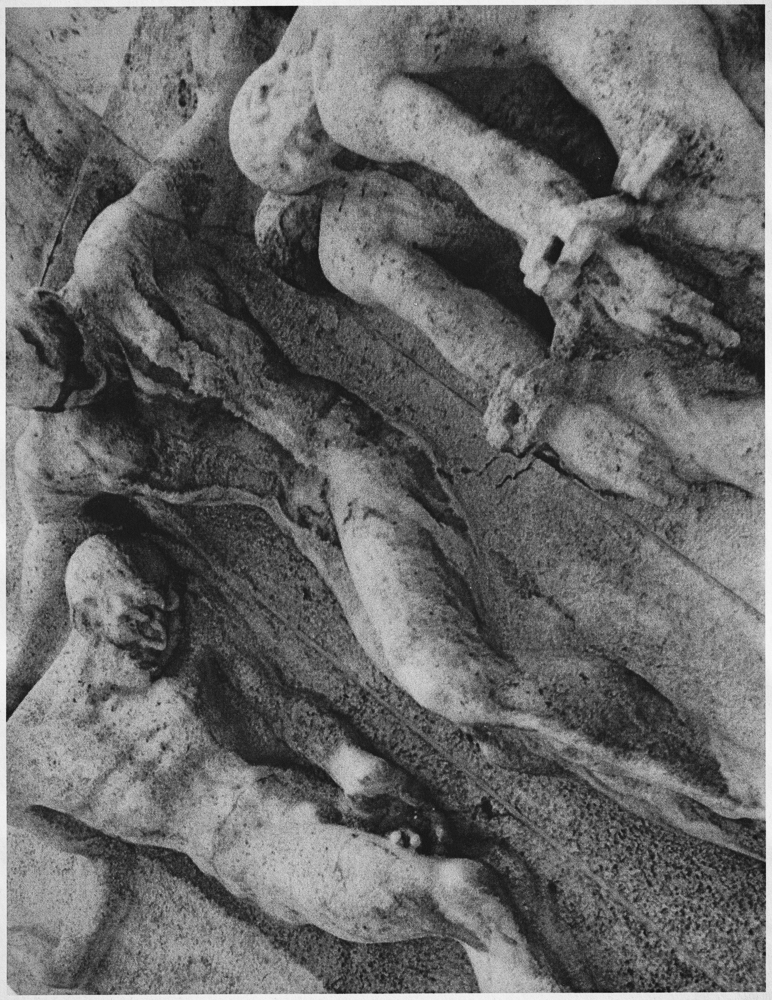

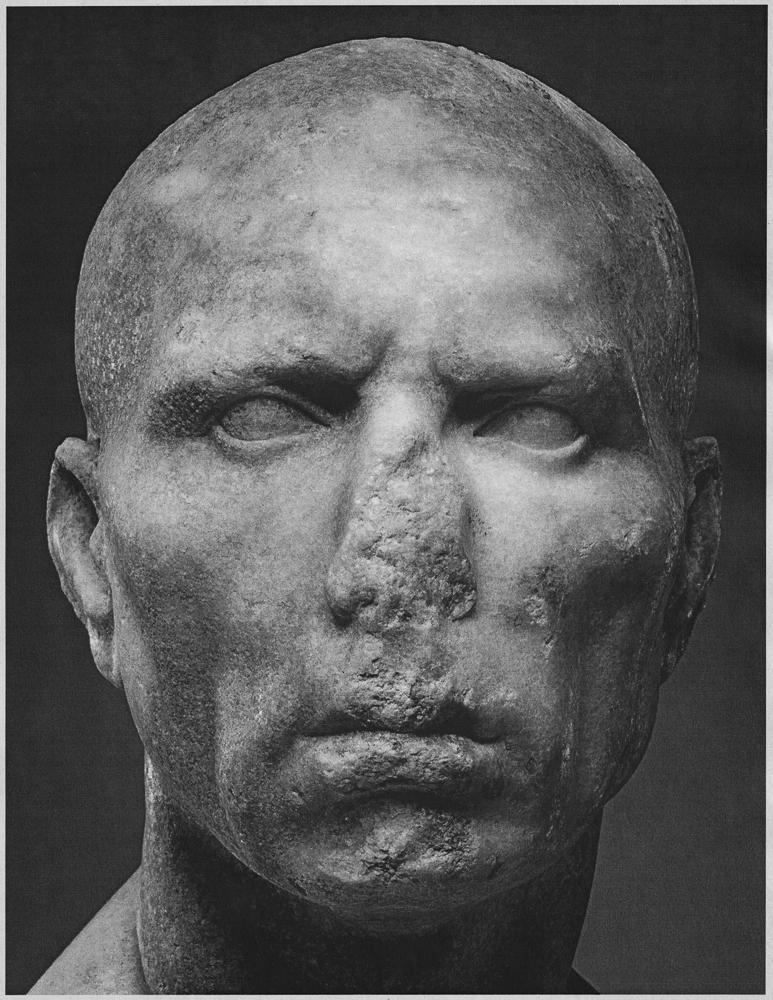

I am a photographer / multi-media artist based in Asheville, N.C. Using both personal photographs and public domain archival images as raw materials, my work combines various materials and methods (e.g., physical print experimentation, dramatic recomposition, and rephotography) to transform subtle feelings into tangible visual expressions. Rather than adhering to strict themes or concepts, I view each image as part of an ever-evolving landscape that mirrors the shifting contours of my perception and my emotional relationship to the world.

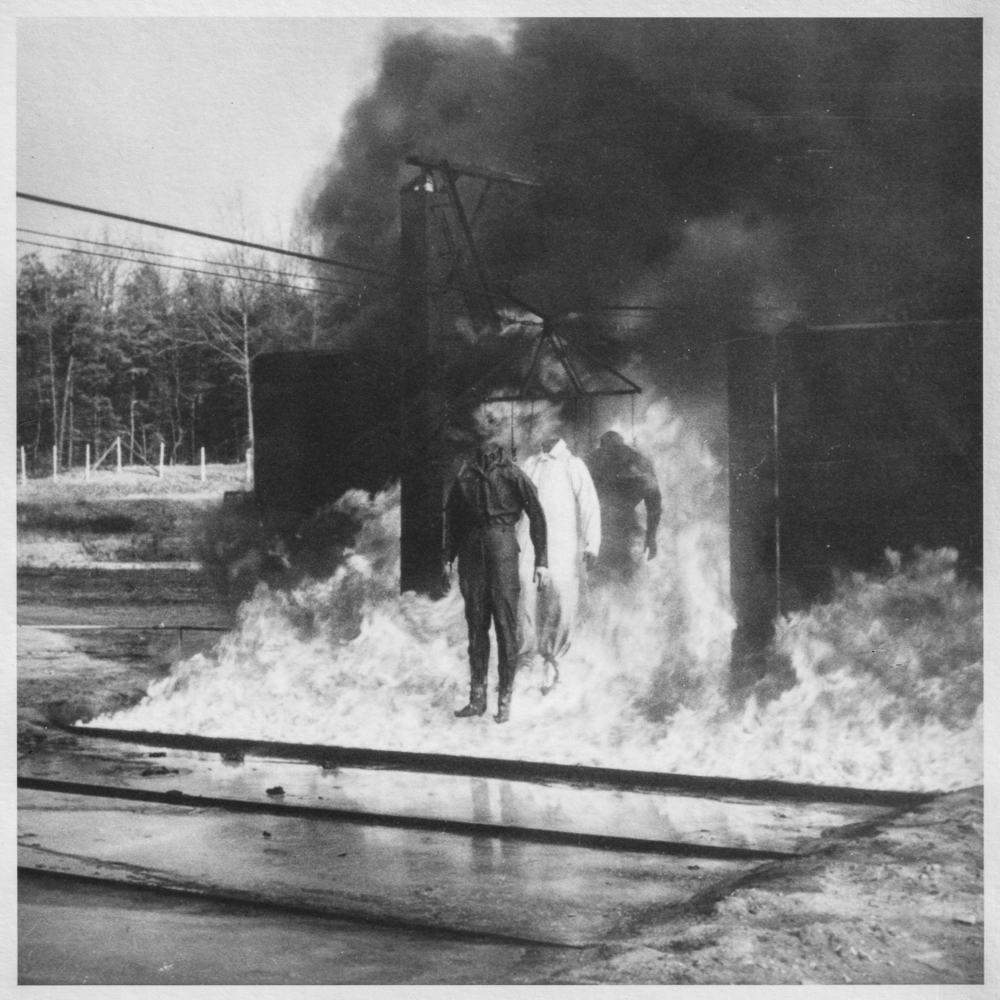

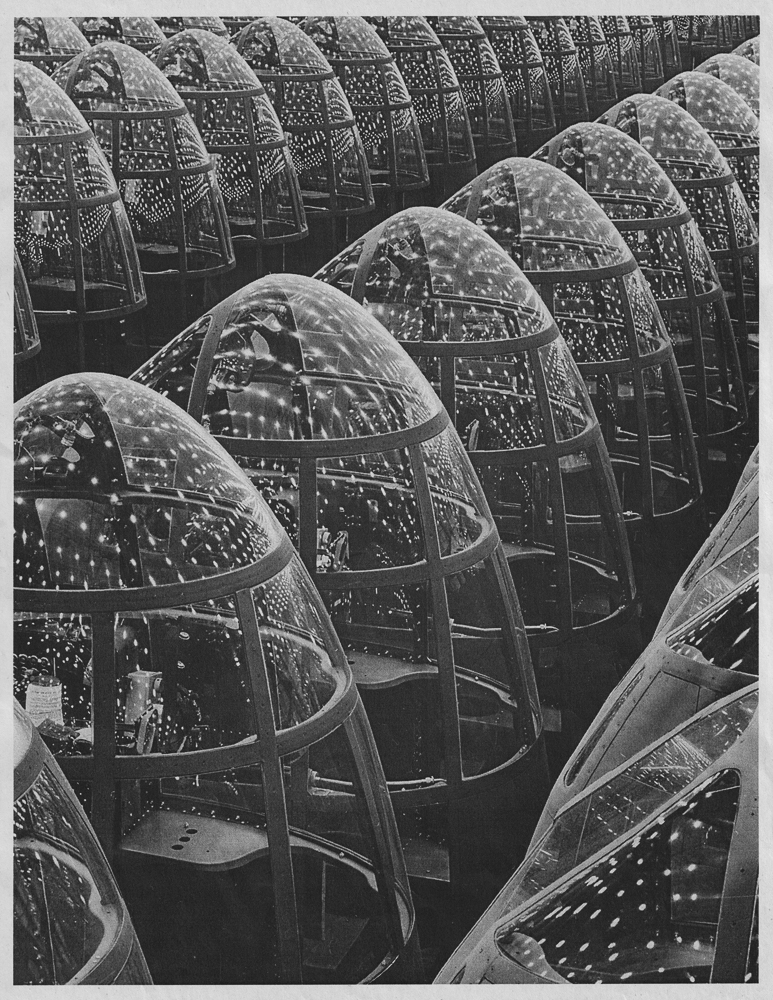

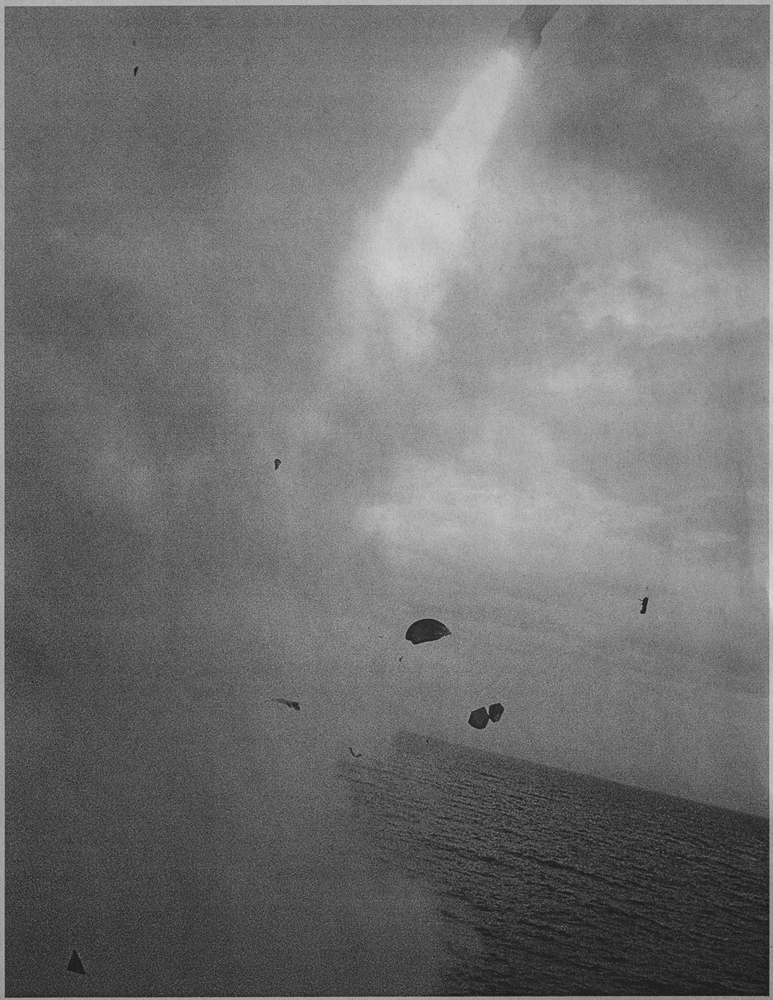

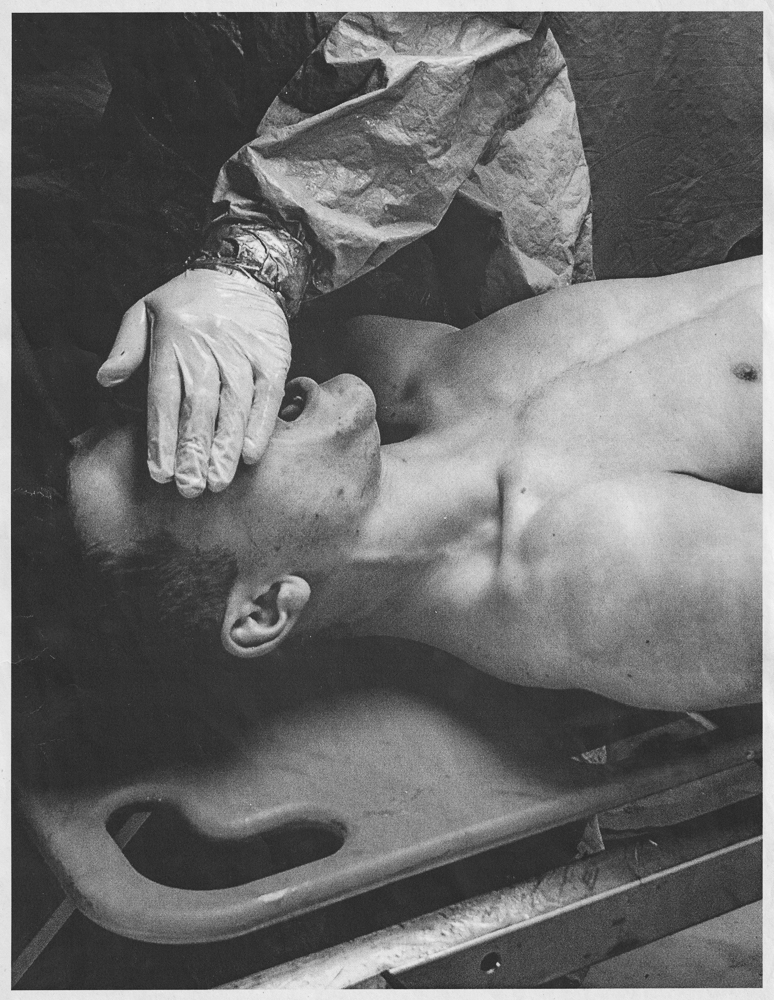

In 2020, a profound personal experience prompted me to reexamine the metaphysical layers of existence, catalyzing a deep dive into mysticism and a fundamental reevaluation of my ontological framework. At the same time, I began to come to grips with the scope of certain devastating realities of life on Earth: the staggering impact of corporate and consumer greed on the environment, the grisly violence perpetuated by the U.S. National Security State and its Military Industrial Complex, and the insidious reach of the repugnant ideologies that sustain these sinister forces.

The images that comprise OF FIRE, FAR SHINING marked my path as I waded through these bewildering experiences and events. While I did not enter the creative space with a predetermined narrative in mind, I am confronted with a sense of anticipation, unease, and foreboding when I view these pieces in retrospect, as if an unseen presence lurks within them, just out of reach, and threatening to emerge at any moment. Ultimately, OF FIRE, FAR SHINING explores what it feels like to be trapped within our highly strange, cataclysmic, and inevitably transformational moment — what Terence McKenna aptly referred to as “the end of history”.

A monograph of this work was published in September 2024. It is currently available for purchase from Zone.

Daniel George: You write that this work is informed by personal experiences and events beginning in 2020. Would you mind sharing more about what prompted you to begin this project?

J.A. Young: Up until the end of 2019, I wasn’t making any visual art. I had never owned a camera, and I wasn’t really interested in making images of any kind. But then, in this weird, intuitive way, I came across this book about optics in a bookstore, which unexpectedly caught my attention. After that, I decided to buy a cheap film camera, and I started making images with that, not really thinking where I was going or having any goal in mind, just following that same intuition. At a certain point, the images I was making started to surprise and excite me—and that’s when it became a process of consciously making visual art.

Then COVID started in 2020, and at that time I was already in the midst of grieving the death of a loved one. I was deeply depressed, and I found myself giving up attachments to all kinds of things: ideas about the world, about humanity, about my future. And I started listening more and more to certain intuitive feelings in my body. I kept entertaining whatever came across my path, as long as it felt intuitively interesting to me, which led me to start experimenting with different ways of understanding the world that I had previously thought were ridiculous. I now understand these as mystical practices, and as I entertained them more and more, I felt more and more creatively alive.

My artistic practice is also connected to a research practice that I have, and my research is guided by the same intuitive process. The subjects I read about are things that come across my path synchronistically. And this research has led me into topics that were darker in nature and that have to do with how humans as a species have abused their own technological innovations, from the cultivation of fire to the advent of agriculture and then all the way to the nuclear era and the age of the internet. Because I was researching this trajectory and trying to understand how one species took an entire planet to the brink of collapse, I began seeking a way to unify this subject matter with my artistic practices. The end result was creating an ongoing project composed of multiple series — the first part of which is a selection of prints I made between 2023-2024 that I call Of Fire, Far Shining.

The ongoing project, which I plan to continue expanding across many years, is about humanity’s unwavering domination over a planet we do not own or understand: drilling into it, covering it with asphalt, building tacky skyscrapers, destroying entire habitats, murdering and torturing ourselves and other animals, throwing our trash all over the place, invading the atmosphere, invading space, and just totally disregarding all the other beings that reside here with us, including the planet itself. Of Fire, Far Shining is my first attempt at organizing these thoughts and emotions into a set of prints imbued with this broader atmosphere.

DG: I was drawn to your use of newsprint, which is such a fascinating medium to work with. For me, I am attracted to its visual language associated with journalism. Tell us more about your choice of materials for these images.

J.A.: I select physical materials based on how successfully they might resonate with the emotions I want to evoke, and I spend a lot of time trying to refine my process around it so that the end result feels correct and consistent to me. I work with different types of paper, different types of printing processes and other materials like chemicals, paint and ink, all of which I use in different layers of my process to alter the image in some way. So, when choosing material, I tend not to start from a conceptual standpoint. It’s usually a sensory or intuitive attraction that leads me to experiment with a particular material, which then creates a whole host of new challenges for me to solve in order to make a print feel correct. In the end, with newsprint in particular, it just occurred to me one day, like any other creative choice, that this was an option. And when I started working with it, I very quickly realized how difficult it is to work with. I had to experiment a lot to get it to work the way I wanted it to work. But once it did start working, I was able to exploit the qualities that I was attracted to originally: the fragility of it, the roughness of it, its color variations, the way it can hold or not hold certain mediums, the way it looks and feels when I rip it and destroy it. So, all of this was prior to and more important than the journalism association, but that definitely was a factor.

I grew up with very few strong associations with photography, and I actually didn’t care much about photography until relatively recently. But I was attracted to the kind of photography I would see at punk shows when I was in high school, and my memory of those was that they had a Xeroxed quality, and they were printed on a very cheap newsprint-like material. Combining that with the history of journalism and newspapers was attractive to me in retrospect, especially when printing archival government photos. I like the idea of taking the associations that newsprint has and turning them on their head, so that now instead of the newsprint holding the words of a journalist telling a story, the newsprint is holding images that I’ve made to capture an emotional atmosphere that can’t quite be put into words.

DG: I am interested to hear about your use of appropriated imagery from the public domain archive and how you consider a recontextualization of history while examining current events. What do you feel these found images contribute to the project?

J.A.: Before I started working with archives in this way, my work felt too removed from the actual subject matter that I was preoccupied with—that I am still preoccupied with—and so my initial move to working with archives was a decision that I made to make sure my work directly connects with my research and the things that I’m processing emotionally on a daily basis. I feel that everything I’m making is trying to describe this situation that human beings have created, in which technology is used not to help the world with its problems but rather to blow things up. And I place a lot of blame on the U.S. National Security State, so naturally that’s where I was drawn first in searching through archives.

When I work from an image that was originally made by a DOD contractor, for example, I’m trying to take what was initially a practical, scientific, documentary photograph and transform it into an object filled with an emotion that captures what I feel to be the true nature of the institutions that funded the original photograph. And in that sense, I do think the archival images are recontextualized in my work. But I’m not consciously trying to retell or recontextualize history.

Whether I’m working with my own negatives or with materials I source from public domain archives, I work on all of them in the exact same way. I have no loyalty to the original image. None of these materials mean anything to me until I’m actively deconstructing them and tearing them apart, sometimes literally, in my studio and my darkroom. When I start working on an image, I’m completely altering the composition, the tones, the atmosphere; I’m adding or removing people and objects as I see fit. I’m always trying to discover new ways of breaking images down further, and I’m altering them through every layer of my process.

DG: I am curious about the book, which is described by the publisher as being “devoid of classical ordering principles.” Would you talk about your approach to sequencing and your thoughts on mediating narrative through this process?

J.A.: I go to great lengths to keep my project unified in its atmosphere and its tone, in the look and feel of the physical objects I’m making. Each print is meant to function on its own, as a piece of a greater fractal, and my goal is for all the elements of the whole to be revealed in the parts. This is the way this moment feels to me and the way time and memory and history feels to me, and I don’t think the way I process reality is best represented in any kind of linear narrative.

So, if I’m going to make a book or an exhibition, or anything where the images have to be put in an order, I don’t want the viewer to be able to grasp onto the standard tropes that we expect in any kind of story or even to find a narrative arc. Of course, some sequences are going to be more effective because certain images will land better if they’re next to certain other images, but in general I think of what I’m making as a giant constellation of prints. Within this constellation, there are smaller constellations, and within those constellations there are patterns and repetitions that I usually see in retrospect. This kind of narrative clustering is closer to what I am after than any kind of single linear storyline. I just want the emotions I was feeling when making any given print to be somehow communicated and transmitted to the viewer in a way that bypasses their intellect so that their unconscious mind can take that transmission and interpret it in whatever way feels right to them.

DG: In your artist statement, you state that this work “explores what it feels like to be trapped within our highly strange, cataclysmic, and inevitably transformational moment.” How would you say this is manifest in your images?

J.A.: At this time in human history, I feel that we’re experiencing the results of a long history of bad behavior—results that have been accelerating and compounding exponentially over the past hundred years or so. The moment we’re in feels so charged to me. It feels frightening and claustrophobic. It feels like time is constantly, frantically moving, just barreling towards an extremely disconcerting and ominous turning point or conclusion.

So, when I’m making images, I’m actively generating within myself all of these feelings that I’m experiencing and that I’ve experienced my whole life as a trans, autistic person living in a world dominated by men. And while I’m trying to capture all these things, I’m also trying to show the role of humanity in the midst of all of this, because humanity is driving this process. And I think humanity needs to take a very honest look at itself right now, while we still have the ability to sit and process what we’re doing. At the moment it feels like human beings are just standing around on the trash heap we’ve created, waiting for something to come out of the sky to destroy everything. So, I’m feeling a lot of grief for the beautiful things that have been and will be destroyed by humanity. Because even though things feel unstable and frightening and sad, I’ve never experienced so much beauty in my life as I am now. Every detail of every sensation that I experience when I’m aware of it feels absolutely precious.

And another part of it is just that I love making art. I don’t have a lot of hope for the way things are going on our planet, but I feel so much love as I’m making art, and that’s the guiding thing. That’s why, even when I’m making images of things that are terrible, I just naturally want to make them as beautiful as possible. My goal is to infuse each image with this raw, real emotion, this combination of wonder and horror, so that I can approximate what I’m going through day to day, living through this particular period in history.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 2January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photography YOU Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 3January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph YOU Took in 2025, Part 4January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025 Exhibition, Part 5January 1st, 2026

-

The Favorite Photograph You Took in 2025, Part 6January 1st, 2026