Elijah Howe: Chained Rock

Chained Rock is a place that exists somewhere between fact and fiction, danger and devotion. In this interview, I speak with Elijah Howe about his expansive, multi-faceted project that documents the imagined town of Chained Rock, Kentucky—home to a population living beneath the threat of a massive boulder and rising river waters. Blending documentary photography, archival material, and hand-crafted objects, Howe builds a world grounded in real encounters and personal experience, while also inviting us into something more mythic. Elijah is a friend, and I’ve had the joy of watching this project take shape over the past few years—often wondering, how does crafting a real live banjo from scratch fit into this photographic endeavor? We talk about authorship, authenticity, the emotional resonance of place, even if a fictional one.

The following is a interview with Tracy L Chandler in conversation with Elijah Howe.

TLC: So I tried to look up the town Chained Rock, Kentucky on the map and couldn’t find it. What’s up with that?

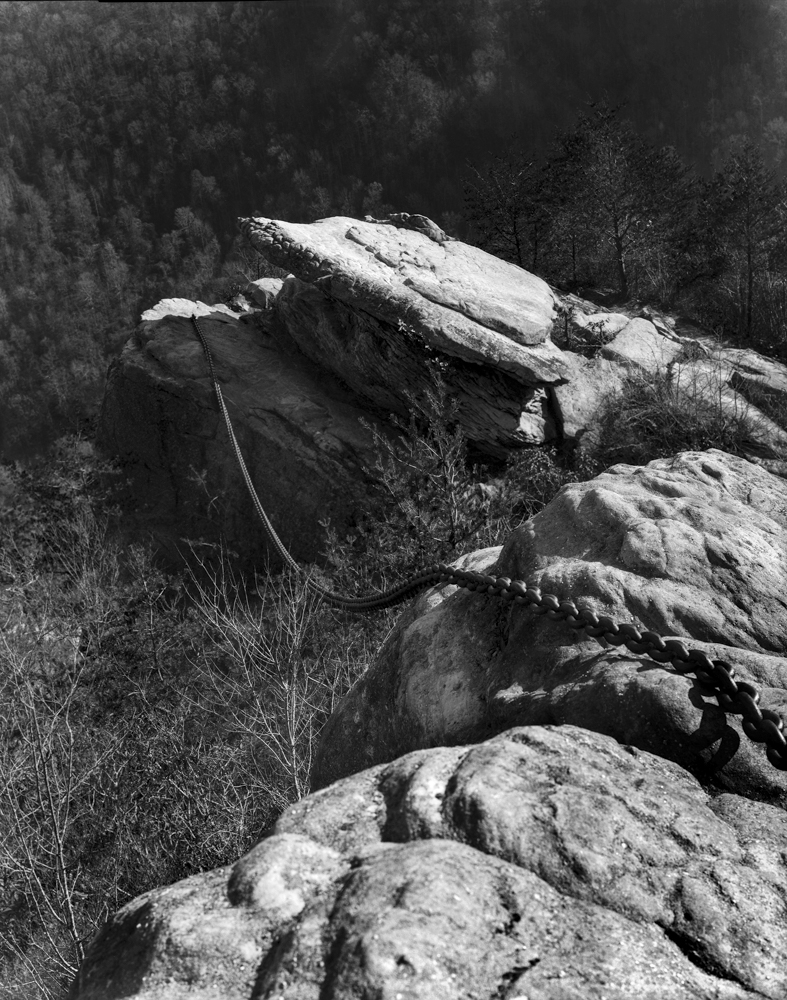

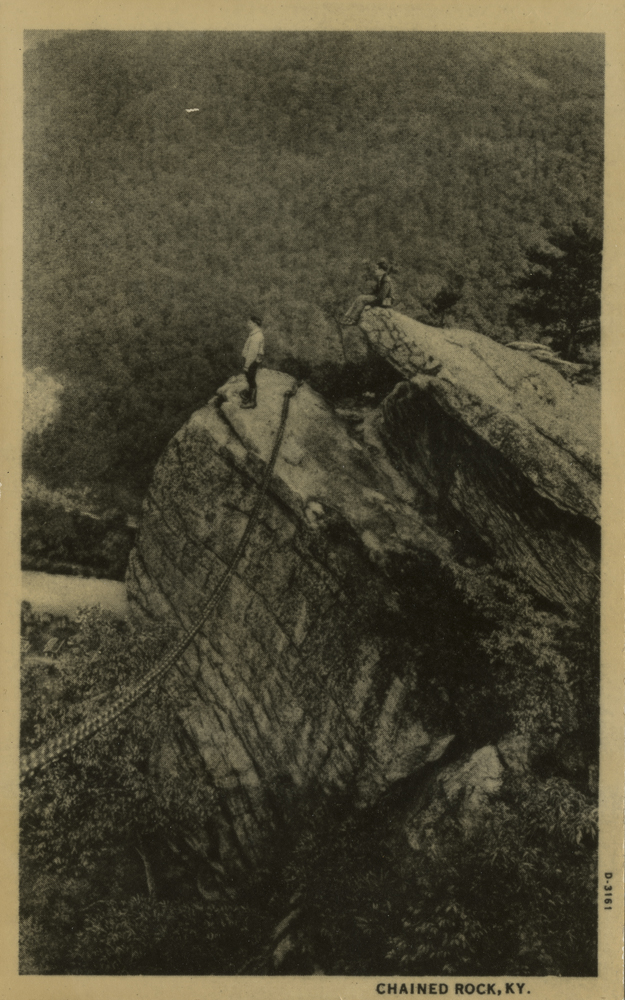

EH: The landmark Chained Rock can be found on the map but the town Chained Rock does not exist. When beginning this project I had the intention of creating a fictitious town in Kentucky based on the real lives, stories, and experiences of people I encountered across the state. This project was photographed using the mechanics of documentary photography but I had a problem with the idea of my photographs determining what is true and real about a location or community. I did not want to pretend to be an authority about a place and its people. I was trying to determine the landscape and history of this fictitious town in response to the story that was emerging from the photographs I was taking. While photographing in Bell County I stumbled upon Chained Rock and fell in love with its history and the metaphor of this giant boulder hanging over a town with just a single chain keeping it from falling. It was literally a balance between the beauty and danger of nature. That became the geographic center point below which my fake town would exist. The town is named after the Rock that threatens to destroy it.

TLC: I get it. It’s like fiction but based on a true story. Or maybe “stories” is a better way of putting it, multiple perspectives, including yours. How did this precarious rock and its metaphorical threat affect what you chose to photograph? How did you choose your subjects? Did the people you photographed know they were playing a part?

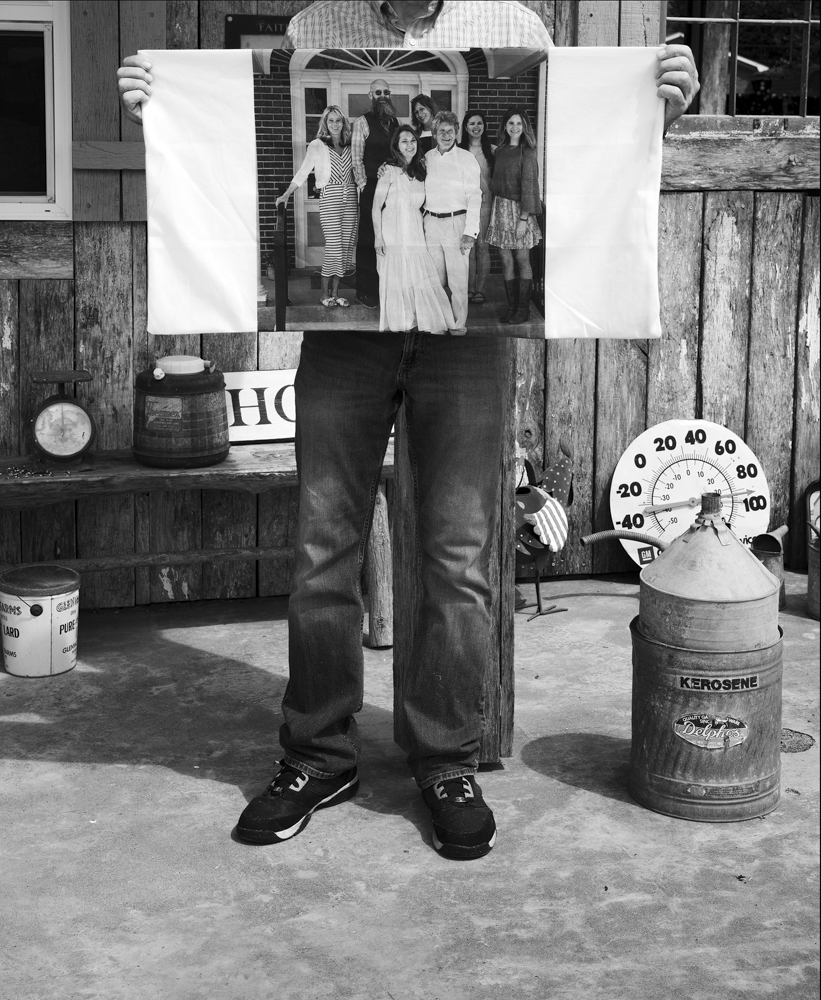

EH: I actually didn’t necessarily choose what to photograph as I was doing it. I like to take pictures now and ask questions later. The people I photographed were largely just people that I came upon in interesting situations (piles of rubble, train tunnels by the river, weird car dealerships, etc). I would talk to them for a while and if it felt right I would ask to take their portrait. A lot of these people shared stories of hardship and hope that felt deeply human and made sense in the town of Chained Rock, but that didn’t really solidify in my mind until later. The parts just kind of came together on their own. The people I photographed didn’t think of themselves as playing a part in a fictitious story, based on reality, because most of them seemed largely uninterested in the pictures as a “project” at all. I would tell them that I am a photographer who’s working on a project about Kentucky but it’s maybe not really about Kentucky and that I didn’t know what it was about yet. In the beginning it was about experiencing things earnestly, spending time with a place and its people. The same way I was engaging with the objects in the project.

TLC: It all sounds very organic, and I know the kind of picture-making you are describing…meandering through a place, spontaneously responding to the physical space and its people. But I’m wondering if and when it clicked into a different gear for you and became a more conceptual endeavor. Was there one particular photograph or event that took things in a more intentional direction? You mention the “objects”, those aren’t something you happen upon—you quilted, you painted, you made video installations, you crafted a banjo from scratch… This is far beyond a meandering post-documentary photo story.

EH: I think there were two main shifts in the direction of the project. I was making the photographs and not quite sure what the project was but I just kept photographing and thinking about what my pictures of Kentucky are doing that others are not. Around this time I was visiting a lot of local museums in various towns to look for guidance on interesting things to photograph in the area. At the same time I learned about a project that my friend Kurt Ghode was working on involving the history of the ‘Kentucky Meat Shower’. The Meat shower was an event in Olympia Springs, Kentucky where it rained meat in 1976. The project is a combination of truth, fiction, past and present in a really interesting and complex way. This made me think about ideas of authenticity and objectivity in documentary photography, which is the approach that I was taking to making these pictures. I was also looking at projects like “Fauna” by Joan Fontacuberta, “Wisconsin Death Trip” by Michael Lesy, “Evidence” by Larry Sultan and Mike Mendel, and “RedHeaded Peckerwood” by Christian Patterson. All of these projects combined the real with the fake to make something that lived in between these absolutes and engaged with history and research in an interesting way. I started collecting and making objects and modifying them to exist in a fake small town museum reminiscent of the ones that I had been visiting. This museum was intended to complement a separate show of my “contemporary documentary photography project” about the same town. This is when the idea of a town trapped between the Chained Rock and a roaring river and the building of the history of a place began. It is also how I started down the path of creating objects for the project, although only the plaque and some of the “Archival” photographs remain from this idea. The second shift came when I realized that a lot of the object creation and the fake museum felt like it was intended to convince or trick the viewer into believing that the town was real. I decided that the town being real or fake was important but it wasn’t the main point of the project and that nobody would doubt the town’s existence in the first place (unless they Googled it). The thing that felt more important was the human experiences and resonance between the depiction of this community and the viewers of the project.

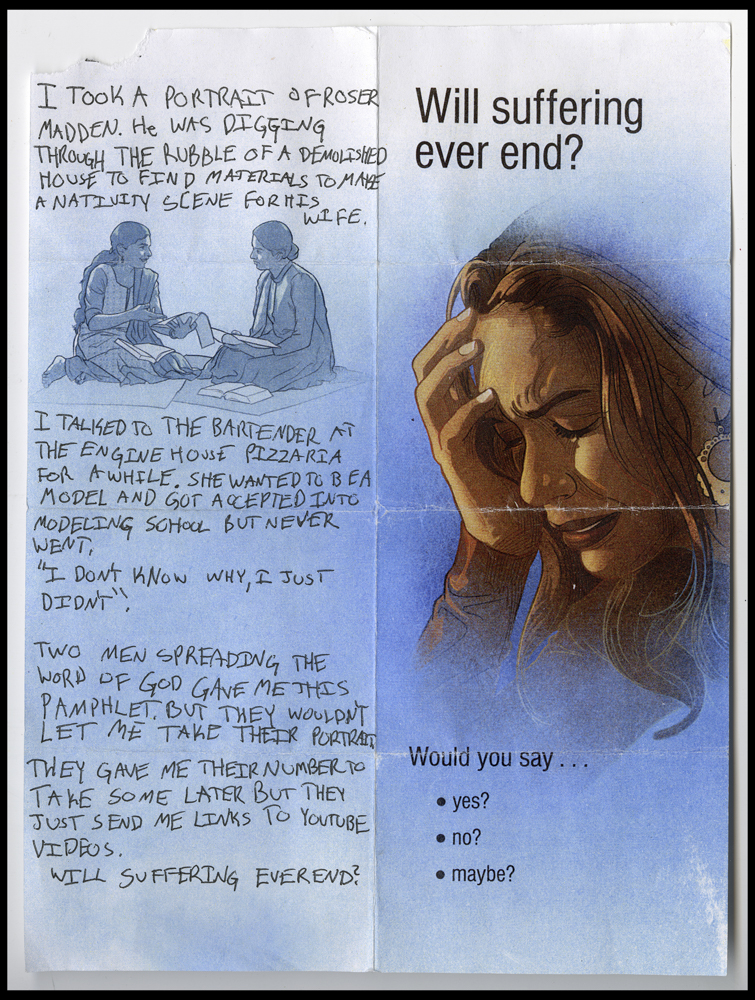

TLC: And really, who is to say what is real or true… The Chained Rock does indeed exist. The people and places you photographed do indeed exist. These photographs and these objects you made do indeed exist. It’s the context you have them in that makes this “art”, conceptual or otherwise. It is interesting how we as humans want to know. Our egos need certainty and to be right. We get scared of uncertainty and want to pin things down into known categories and labels. I feel like this meta understanding mirrors the content of the story you are telling with these photographs and objects… the precarity of a town trapped beneath a lingering danger.. with the tension of uncertainty of if/when things will fall apart. In one of your pieces, you have notes about your interactions with townspeople written on a christian missionary pamphlet asking “will the suffering ever end?”. Then it offers a multiple choice answer “Yes?, No?, Maybe?.” This pamphlet presupposes there is suffering, suffering that has potential to end. Do you agree?

EH: Exactly. One of the things that I love about this project is that everything feels real and true to me. The town is real to me, and while photographing, meeting people, and by making these traditional time intensive objects I am participating in it. The pamphlet offers a solution to these three possible options but for me it just resulted in unwanted youtube links about Jesus instead of any sort of clear solution. The people of this town decide to stay there even though it is on the brink of destruction. They don’t stay hoping the river will dry up and the rock will disappear removing those two points of “suffering”. Suffering is human. They stay there because it is home and it is beautiful and important in the face of the danger and turmoil it may provide.

TLC: Good point. It’s very zen in a way. Can you sing me your favorite part of the Chained Rock song you wrote for the banjo?

EH: It’s hard to choose a favorite because nothing really stands alone in the narrative. This might be my favorite though because it’s the first thing I wrote that felt like a real song was emerging:

Daddy died at fifty-five

Chained Rock just sat and watched

I buried him up on the hill

Beneath a wooden cross

I hope the hill will keep him safe

From the river down below

One day I know it’s going to rise

And take everything I know

TLC: The anxiety is palpable but it’s also quite sad really. How much would you say Chained Rock reflects your own psychological state? I met you when you were showing your project Mike. Was he 55?

EH: A lot of the music I listen to has this kind of upbeat feeling to it but has really heavy and dark lyrics. I wanted to do something similar. The lyrics to the song were based on my own life when I began writing it. I read “The Songwriter’s Handbook” by Tom T. Hall while researching how to write a song for this project and one of his first pieces of advice is to write about what you know. Seems simple.

He was 36 days from 56. That might be a better lyric.

TLC: Yeah, I figured. The tragedy of untimely death…we have much to discuss on this topic. Stay tuned for next time.

EH: Staying tuned.

Chained Rock will be on view at 2nd Story Gallery in Lexington Kentucky through May 16th 2025.

Elijah Howe is a photographer from Humboldt County, California where he received his BA in photography from Humboldt State University. He currently lives and works in Lexington, Kentucky where he is an MFA candidate at University of Kentucky. Howe’s work is interested in the fragmentary nature of photography and people’s relationships with one another as well as their relationship with the land. His work explores quiet transitory spaces in the landscape and the unsettling melancholy of the human condition. He is currently working on a Monograph titled “Mike” with TIS Books and has work in the Permanent collection of the Monroe Moosnick Medical and Science Museum at Transylvania University. He Has recently shown at 2nd Story Gallery in Lexington, Kentucky, Bolivar Gallery in Lexington, Kentucky and Touching Ground Gallery in Georgetown, Kentucky.

Follow Elijah Howe on Instagram

Tracy L Chandler is a photographer based in Los Angeles, CA. Her monograph A POOR SORT OF MEMORY is now available from Deadbeat Club.

Follow Tracy L Chandler on Instagram.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026