Micah McCoy: Minor Prophet

I met Micah McCoy through his work with Disparate Projects. Disparate Projects is an evolving collective and platform dedicated to the exploration of contemporary photography run by Lisa Beard, Micah McCoy, and Vann Thomas Powell. I was familiar with Vann and Lisa through my work with Midwest Nice Art and was so excited to work with Micah when I saw his work. “Minor Prophet” is an exploration of family and spirituality over the years. Time-based work is always intertwined with ideas of nostalgia, looking back on the past. When it comes to family, this can be difficult in a number of ways, from your personal feelings of an event to consideration of the role the photographer has in retelling these stories. The series plays with ideas of fiction and truth through the existential crises of our lives.

Micah McCoy is a photographer, curator, and poet based in Northwest Arkansas. He received his MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago (2022) and has exhibited work in solo and group exhibitions both in the United States and abroad. His work explores issues of religiosity, anxiety, and social detachment. Micah’s editorial photography has been featured in publications including NBC News, The New York Post, and others.

He is a co-founder of Disparate Projects, a platform for photographic curation, theory, and publishing, including Disparate Press, which focuses on producing books and zines that showcase innovative photography and collaborative work.

Follow Micah on Instagram: @micahmccoy

Minor Prophet

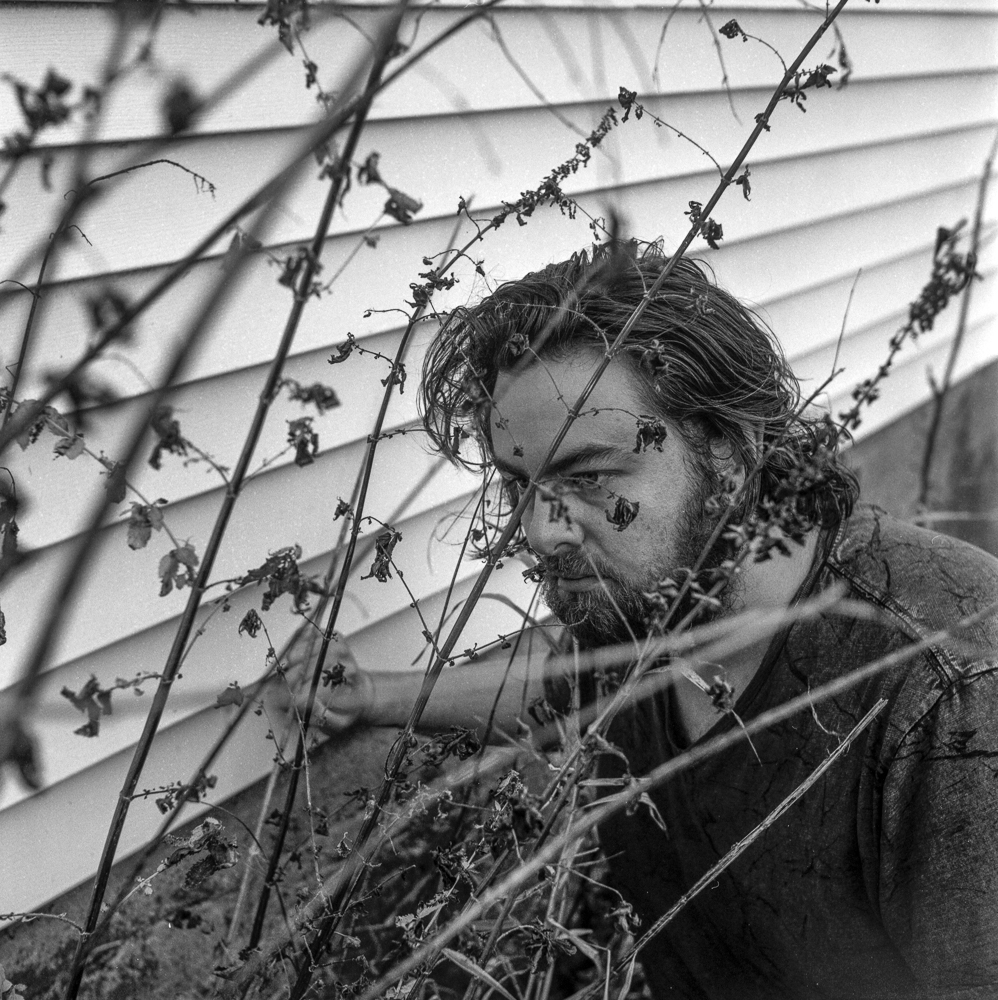

Minor Prophet is loosely based on the Judeo-Christian story of Job, and witnesses a family faced with existential crisis in a chillingly desperate landscape. Centering around the family home, the photographs chart the psychological space of my family’s private inner world. As I’ve photographed our farmhouse, the surrounding lands and took portraits of myself and my family, I began to see our home as a canvas on which the various sectors of our consciousness were laid bare.

This series blurs the line between traditional documentary and the fictional, leveraging the illusion of photographic truth to allow the individual characters in the narrative to function as surrogates in myth-making. The resulting fable is scaffolded by photographic strategies that reinforce the monumentality of the biblical origins inherent in the work. The series focuses on the frailty of human life, contrasted with the resilience of the land. Precise sequencing allows an open-ended narrative to crystalize. An amalgamation of portraits and rural landscapes tie the characters to the land, emphasizing the connection between place and its embedded religious history. These photographs act as a modern parable, an updated story of doubt for a modern audience.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Micah McCoy: I had a specific image in my mind for years before starting the project. I was either too scared to go to the places necessary to make the work or apprehensive about what the second image in the series would be. In any case, I let it ruminate for a while before beginning. When I arrived at Columbia College Chicago for graduate school, I knew pretty early on that this was the project I wanted to undertake for the next few years. The work is about the fundamentalist Christian faith tradition I grew up in and its effects on myself and my family. The reception of the work—both in graduate school and in the larger photo community—has been marked by aesthetic and ideological unease. The work engages religious themes in a way that resists clear categorization, and that ambiguity may unsettle a community predisposed to view religion as either oppressive

or irrelevant.

The project, in its settled form, is a kind of parable about a family faced with existential crises and their attempt to reconcile these circumstances with an inherited set of beliefs. I made a decision to distance myself from the ideas by classifying the photographs as fictional rather than documentary in nature, which quite possibly stems from a reluctance to engage with work that does not declare its position outright—neither reverent nor wholly critical. I believe that is where the work becomes interesting, but that is not a judgment I’m in a position to make.

EK: Is there a specific image that is your favorite or particularly meaningful to this series?

MM: This photograph was taken very early in the project and grew in my estimation with each photo I took thereafter. In contrast with an imagined religious future of eternal life, the material world far outlives us. Without the metaphysical, structures like this one are all that remain. This was also important in establishing an aesthetic for everything I would make later. The empty grey sky became something I went back to repeatedly—the default backdrop for my desolate little story.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

MM: I try not to consume much photography outside of that made by my closest friends. I’m constantly consuming history, music, and cinema, merging what I find there with my own philosophy. I do like to look at a lot of early photography. I think early photography created a solid foundation for me to work within, but I sometimes find the insular photo world to be tiresome. I try to focus on keeping my mind open and experimental to allow for new things to find me.

I’ve found sharing my work with a small circle of artist friends to be beneficial—the best way to push forward without falling prey to trends or the disposable. I prefer to let ideas simmer and clarify through thought and discussion. By the time I make a photograph, I’ve hopefully worn away the rough edges, leaving something nearly ready for a final print that fits into an edit of whatever project I’m working on.

EK: What’s next for you?

MM: I’m currently working on a few curatorial projects with my friends at Disparate Projects. I’m excited to exhibit Minor Prophet near where the work was made in Central Illinois this fall and would like to get this work out in printed form by then or shortly after. I’m also working on a project about the folks who believe we are in the end times, as well as a historical novella that will be accompanied by illustrative photographs.

Epiphany Knedler is an interdisciplinary artist + educator exploring the ways we engage with history. She graduated from the University of South Dakota with a BFA in Studio Art and a BA in Political Science and completed her MFA in Studio Art at East Carolina University. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving as an Assistant Professor of Art and Coordinator of the Art Department at Northern State University, a Content Editor with LENSCRATCH, and the co-founder and curator of the art collective Midwest Nice Art. Her work has been exhibited in the New York Times, the Guardian, Vermont Center for Photography, Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, and awarded through Lensculture, the Lucie Foundation, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass.

Follow Epiphany on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026