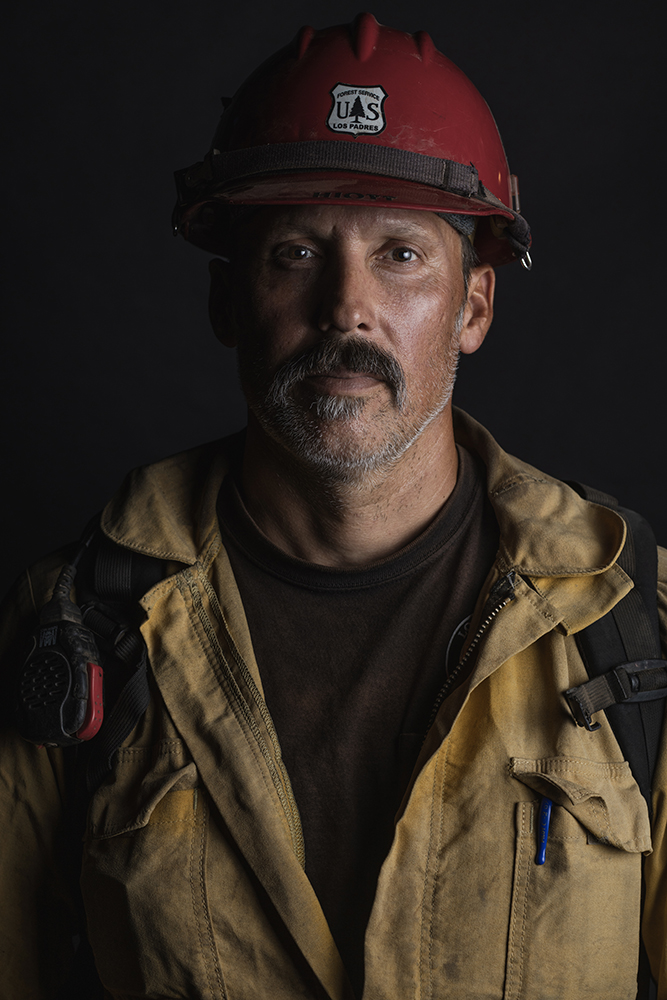

Sean Stanley: Ashes of Summer

Apache, Photographed during a 32-hour shift on the Apache Fire, this image captures wildland firefighter Sean D. Stanley moments after the fire made a hard, unsafe run. Dispatched the night before and working on little to no sleep, the crew had initiated attack at dusk, bedded down briefly in the early morning hours, and returned to the line by sunrise. Taken just as conditions rapidly deteriorated and crews were forced to disengage, the photograph reflects the volatility, fatigue, and split-second decisions that define wildland fire. Image captured by fellow firefighter Jake Riffel on Stanley’s iPhone.

January 8th marks the anniversary of a horrific day in Los Angeles, with fires that stretched from the ocean to the mountains that continued for days, devastating and collapsing neighborhoods and putting the city on edge. Many friends and photographers lost their homes, their equipment, their communities, and their sense of security. For the next three days I am featuring the work of photographers who document fire and it’s aftermath. Today we start with Sean D. Stanley, a former wildland firefighter who witnessed the devastation of fire first hand. His work focuses on “federal wildland firefighting—long days, steep terrain, heavy packs, constant smoke exposure, lack of sleep, and extended time away from family”.

Sean D. Stanley (b. 1987, Los Angeles, CA) is a photographer and former wildland firefighter whose work captures the raw power and haunting beauty of wildfire. Born in Los Angeles and raised in Ventura County in the small town of Moorpark, Sean’s connection to fire began long before he put on the yellow Nomex. Since 2016, he has been documenting wildland fires across California, drawn to the way flame, smoke, and landscape collide in moments of both devastation and resilience.

In 2020, while photographing the Bobcat Fire in Monrovia, Sean realized he wanted to do more than stand behind the lens—he wanted to stand on the line. That decision led him to begin his fire career with the MRCA Fire Division in the Santa Monica Mountains. He then went on to serve three years with the United States Forest Service as a Forestry Technician—though every firefighter knows the title means one thing: wildland firefighter. Stationed on the Ojai Ranger District, he worked on Type 3 engines out of both the Ojai (Engine 352) and Fillmore (Sespe, Engine 354) stations, often pushing through 24-hour shifts and, at times, staying awake and engaged for more than 30 hours straight. Those years taught him not only about fire behavior and teamwork but also about his own limits—physical, mental, and spiritual.

Sean resigned from the Forest Service in November 2024 to pursue photography full-time, carrying with him the hard-earned lessons, respect, and camaraderie of the fireline. His body of work—spanning nearly a decade of photographing wildfires as both a witness and participant—offers a rare perspective. He understands fire not just from the outside but from within: the way it moves, breathes, and reshapes everything in its path.

This work is both a tribute and a thank-you—to the men and women of wildland fire, to those who guided him, to those who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with him on the line, to the countless communities forever changed by fire, and most of all, to the ones who made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives. Through these images, Sean seeks to honor the brotherhood of firefighters, the fragility of the landscapes we protect, and the undeniable force of nature that is wildfire.

An interview with the artist follows.

©Sean Stanley, Bobcat, A Mill Creek Hotshot uses a drip torch to burn out fuels during the Bobcat Fire, 2020, in Monrovia, California, as part of an effort to stop westward fire spread.

Ashes of Summer

I began photographing wildfires in 2016, drawn to the raw force and haunting beauty that fire creates across the landscape. At first, I was responding purely as a photographer—trying to understand how something so destructive could also be visually overwhelming and deeply emotional. Over time, that curiosity evolved into something much more personal.

In 2021, I became a wildland firefighter, and from 2022 to 2024 I spent three years working for the U.S. Forest Service. Being on the fireline fundamentally changed how I see fire, photography, and the people who fight these incidents. I witnessed firsthand the reality of federal wildland firefighting—long days, steep terrain, heavy packs, constant smoke exposure, lack of sleep, and extended time away from family. This work is physically demanding, dangerous, and largely unseen by the public.

Most people associate wildfire suppression with bright red municipal fire engines and structure protection. While those crews play an important role, the federal wildland firefighters—the men and women on hotshot crews, Type 3 and 6 engines, helicopter crews, and Type 2 hand crews—are often overlooked. I’ve experienced moments where members of the public mistook my crew for trail maintenance workers, unaware that we were actively constructing handline or laying hose on major wildfires.

I also want this work to show the unglamorous reality of the job—sleeping on the ground near the fire, being gone for weeks at a time, the long-term health risks, and the toll it takes on the body and mind.

These photographs offer a glimpse into places and moments the public rarely sees. More than anything, this work is about respect—for the land, for the fire, and for the people who dedicate their lives to fighting it. – Sean Stanley

©Sean Stanley, Bridge Fire– Seen from inside a responding fire engine on the second day of the Bridge Fire, this photograph captures the blaze in September 2024 as it made a massive, wind-driven run. Igniting the day prior, the fire rapidly escalated in size and intensity, burning more than 30,000 acres within a single day. The image reflects the moment crews confronted the scale, speed, and volatility of the incident upon arrival.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

I grew up in Moorpark, California, in a supportive home with parents who encouraged me to pursue whatever I was passionate about. Skateboarding and surfing played a big role in my early life, and those worlds naturally pulled me toward photography. In middle school, my parents gave me a small point-and-shoot camera—likely a Sony Cyber-shot—and I brought it everywhere, photographing skateboarding, waves at the beach, and moments with friends. I also remember carrying disposable cameras on family trips, already drawn to documenting the world around me.

In 2008, I attended the Art Institute of Santa Monica to study graphic design, where I was placed into a photography class. That experience sparked my first real interest in photography, and I bought my first DSLR, a Nikon. Although I eventually stepped away from that career path, I never fully put the camera down and continued shooting casually over the years.

In 2015, everything shifted when a friend invited me to assist on a professional photo shoot. Seeing the images he created and the way he worked made me realize photography could be more than a hobby. A few months later, I invested in my first professional camera setup—a Canon 5D Mark III with a 24–105mm L-series lens—and began taking photography seriously.

Since then, photography has become the foundation of my life and career. Over the years, I’ve photographed professional surfers and action sports, weddings, portraits, commercial projects, and more recently, architecture. What started as curiosity with a simple camera has grown into a lifelong pursuit of storytelling through images.

©Sean Stanley, Chaos, Photographed on December 4, 2017, this image documents the Thomas Fire as extreme Santa Ana winds drove the fire at an alarming rate through Ventura County. Amid rapidly deteriorating conditions, the scene descended into chaos as law enforcement, firefighters, and members of the public scrambled to evacuate residents and move horses and other animals to safety. The photograph reflects the overwhelming sensory intensity of the moment—fire, wind, smoke, and sound converging as the fire surged forward.

How did the dual careers as a photographer and a firefighter begin?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I was consistently working as a photographer alongside my close friend and collaborator, Ricky. Together, we were shooting weddings and commercial projects, including campaigns for brands like Little Tikes. Photography was my primary focus and income at the time.

When the pandemic hit, nearly all of that work disappeared almost overnight. Like many creatives, I suddenly found myself without steady income and relied on working at a friend’s surf shop to stay afloat. During that same period in 2020, I was photographing the Bobcat Fire in Monrovia—something I had already been doing independently since first photographing wildfires in 2016, driven purely by fascination and the need to document them.

While on the Bobcat Fire, I met a municipal firefighter assigned to structure protection. In a casual conversation, he suggested that I consider becoming a firefighter myself—someone who could work fires from the inside while continuing to document them. At the time, I didn’t act on it, but the idea stayed with me.

With photography work slow to recover, I decided to take that suggestion seriously. In 2021, I joined the MRCA Fire Division in the Santa Monica Mountains as a volunteer wildland firefighter. There, I trained extensively and completed a basic wildland fire academy, earning my certifications and gaining firsthand experience on the fireline.

In 2022, as photography had still not fully rebounded, I committed fully to wildland firefighting and began working for the U.S. Forest Service. I spent the next three years, from 2022 to 2024, stationed on the Ojai Ranger District. During that time, I continued to take on photography work whenever possible, primarily during days off and winter months when fire activity slowed.

Over time, the two paths—photography and firefighting—became inseparable, each informing how I see, document, and understand wildfire and the people who fight it.

©Sean Stanley, Darkness, Photographed during the French Fire in August 2021, this image captures the head of the fire continuing to burn aggressively as night fell. After an active day of fire behavior, the blaze maintained intensity into the evening, consuming both live and dead vegetation. The photograph documents the persistence of large wildland fires beyond daylight hours, revealing a scene that was both destructive and hauntingly beautiful.

How many different fires did you encounter? All in California?

As a firefighter, I lost count of how many fires I responded to. Many were small initial-attack fires that were contained at less than an acre, while others grew into large incidents. There were also fires that became significant but were already controlled by the time our resource order came through.

All of the fires I worked on as a firefighter were in California, spanning a wide range of terrain and fuel types. These included incidents in Ventura County, Santa Barbara County, Los Angeles County, San Bernardino County, Fresno County, San Luis Obispo County, Mariposa County, and Stanislaus County, among others.

Prior to becoming a firefighter, the wildfires I photographed were also all in California—many of them in the same counties I would later work in on the fireline.

Photographing these landscapes before and after becoming a firefighter gave me a deeper understanding of fire behavior, scale, and impact across the state.

©Sean Stanley, Feds, U.S. Forest Service Engine crews from 1652 Charlie Strike Team stage on the Bridge Fire, September 2024. Often overlooked or mistaken for Cal Fire or trail workers, the green engines of the Forest Service represent the federal wildland firefighters who make up the backbone of large wildfire suppression. While municipal fire departments play a critical role in structure protection, it is federal and interagency crews who spend days and weeks hiking steep terrain, laying hose, and cutting handline to contain fires across vast landscapes. The image highlights the largely unseen workforce responsible for stopping wildfires at their source.

How does documenting the power of the flame change the way you see fire? And what is the experience of visually revisiting these episodes?

Documenting the power of wildfires has completely changed how I look at it. Early on, I was drawn to it for its visual intensity, the scale, movement, and light were impossible to ignore. But over time, especially after working as a wildland firefighter, fire stopped being abstract or cinematic. It became personal.

Visually revisiting these moments is often grounding and unsettling at the same time. The photographs bring back the physical sensations—the heat, exhaustion, adrenaline—but they also create distance. Through the frame, I’m able to reflect on fire not just as destruction, but as a force that reshapes landscapes, communities, and the people who confront it. Photography becomes a way of slowing down and processing something that, in real life, is chaotic and relentless.

©Sean Stanley, Fireworks, Photographed on the first night of the French Fire, this long-exposure image isolates a single tree continuing to burn after the fire front had passed. Wind-driven embers streak across the frame, creating a visual effect reminiscent of fireworks, while revealing the persistent heat and residual energy left behind in the wake of a wildfire. The photograph documents the quieter, less visible phase of fire behavior that unfolds after the initial run.

What do you hope the viewer takes away from the work?

I want the viewer to experience what it’s like to be on a major wildfire incident up close and personal. I want them to understand what federal wildland firefighters endure during a 14–21 day assignment—the 16+ hour days, the physical exhaustion, and the mental strain that accumulates over time. What the public rarely sees are the personal sacrifices: being away from family most of the summer, the stress placed on relationships, and the long-term toll the job takes on the body and mind.

I also hope viewers understand that these photographs are not simply images of destruction, but records of history. Fire is a natural and necessary part of our ecosystems. Our forests and wildlands depend on low-intensity fire to remain healthy—clearing forest floors, renewing soil, and allowing new life to emerge. That perspective is something I learned firsthand through firefighting. This work is meant to show both the reality of the fireline and the deeper relationship between fire, land, and the people tasked with holding that balance.

©Sean Stanley, Gone, Photographed on the fire line during the Bridge Fire, this image captures the sheer force and destructive power of extreme wildland fire behavior. Shot while crews worked to extinguish hot spots along the western flank, the fire made a hard, wind-driven run through steep terrain directly ahead. The photograph documents a level of fire intensity rarely seen, revealing the scale, speed, and volatility confronting firefighters on the line.

Is there something profound you want to share from your experiences?

You know, I learned a lot about myself—what my body can handle and what my mind can do under stressful situations. I learned about pushing my body through training to a level I didn’t realize I was capable of. I believe every single person is capable of doing great things, and stepping outside your comfort zone to grow is something I think everyone should at least try. It doesn’t have to be something like firefighting, but we are all resilient human beings capable of more than we realize. We just have to push ourselves outside our comfort zones, and that idea can be applied to anything.

Don’t be afraid to fail either. I did—quite often—with both fire and picking up a camera. Failure is where the growth happens.

©Sean Stanley, Hiott, Paul Hiott, captain of Los Padres National Forest Engine 51 out of Casitas, California, on the Ojai Ranger District. With 24 fire seasons in the U.S. Forest Service, Hiott has dedicated his career to leadership, mentorship, and training the next generation of wildland firefighters. He began his career on the Sundowner Handcrew and has served on LP Hotshots, Type 3 engines, and as a helicopter rappel firefighter working off Helicopter 528. Since 2018, Hiott has led the Sundowners Type 2 Handcrew, continuing a long tradition of developing disciplined, highly skilled crews. A steady and respected presence on the fireline, he represents the professionalism, experience, and quiet leadership that define federal wildland firefighting.

What or who inspires you?

Photography itself is a constant source of inspiration for me. I’m always learning—whether it’s discovering new ways to approach a subject, experimenting with different lenses and techniques, or exploring new editing styles. That ongoing process of growth keeps me motivated and curious.

I’m also inspired by other photographers, especially friends who work in both stills and motion. Seeing how they approach storytelling visually pushes me to think differently about my own work. Old surf magazines and surf imagery I come across online still fire me up as well; those images were some of the earliest influences on how I saw photography and movement.

Most importantly, my parents inspire me. They have never given up on each other or on me,and they carry an incredibly positive outlook on life. Watching their resilience, support, and optimism has had a profound impact on who I am, both personally and creatively. I’m deeply grateful for everything they’ve shared with me and the foundation they’ve given me.

©Sean Stanley, Hoselay, A federal wildland firefighter works the fire line during the French Fire near Lake Isabella in Kern County, California, August 18, 2021. Often overlooked, federal crews operate in some of the harshest conditions on wildfires—frequently in temperatures exceeding 100°F and during 12–16 hour shifts. Unlike municipal firefighters, wildland crews do not wear respirators, carrying instead packs weighing roughly 45 pounds, often supplemented by hose packs or chainsaws adding another 25–30 pounds. Alongside extreme heat, firefighters contend with heavy smoke exposure, falling snags, rough terrain, limited sleep, dehydration, and repeated aerial water or retardant drops. The image documents the physical and environmental toll inherent to wildland firefighting.

Now that you have stepped away from firefighting, what are you focusing on?

Much of my time and energy is currently focused on bringing my book Ashes of Summer to life. I’ve been actively seeking an institution, such as a museum, to support the project through an exhibition and book sale. I’ve also been in conversation with Rizzoli about publishing the book and am continuing to look for the right partners to help move it toward print.

Alongside the book, my photography career has become a major focus since stepping away from full-time firefighting. Work has been steadily increasing, with more weddings, real estate shoots, and personal portrait projects filling my schedule.

While I’ve stepped back from federal fire, I haven’t fully left the fire world. I recently joinedthe LA Community Brigade, which partners with Los Angeles County Fire. The program focuses on helping communities harden their homes against wildfire risk and provides support during wildfire incidents in the Malibu Division 7 area. Staying connected to fire in this way feels meaningful and aligned with the larger purpose behind the work.

Thank you for all you have done to protect our state. Truly heroic!

©Sean Stanley, Nightshift, A short module from a wildland hand crew conducts night operations during the Bobcat Fire, 2020. Assigned to burn out and hold along a roadway, the crew worked through the night to prevent rolling material from igniting spot fires below the slope. Often unseen and far from glamorous, night shift assignments are a critical part of wildfire suppression. Crews are frequently placed on day or night shift regardless of prior rest and remain assigned for up to 14–21 consecutive days, a schedule that compounds fatigue while demanding constant vigilance in hazardous conditions.

©Sean Stanley, Thomas Fire, Photographed six days into the Thomas Fire, this image was captured from Ventura Harbor and reveals the immense scale and force of one of California’s most destructive wildfires. Towering smoke columns rise above the coastal landscape, underscoring the magnitude of the fire’s growth and the destruction left in its wake. The photograph places the viewer at a distance, emphasizing how far-reaching and dominant the fire had become across Southern California.

©Sean Stanley, Waterdrop, A helicopter conducts a water drop on the French fire in support of ground crews during wildfire suppression. Aerial drops play a critical role in cooling hot spots along the fire line, supporting mop-up operations, and slowing fire spread in areas difficult to access on foot. Beyond suppression, helicopters provide essential intelligence from the air, relaying real-time fire behavior that is often obscured from the ground by smoke, terrain, and limited visibility. Frequently overlooked, aerial resources remain a vital and coordinated component of modern wildland firefighting.

©Sean Stanley, Wildland Firefighter, A member of the Mill Creek Hotshots monitors a freshly burned section of fire line after a burnout operation. The image was taken at the beginning of a shift that would extend through the night and into the following morning. Federal Hotshot crews represent the highest level of wildland firefighting, specializing in long, grueling assignments that demand precision, endurance, and constant situational awareness. Often mistaken for other agencies, Hotshots are routinely tasked with the most complex and dangerous portions of a fire and play a central role in bringing large incidents under control.

©Sean Stanley, Yosemite, Photographed during the Red Fire in the remote backcountry of Yosemite National Park, this image captures the Milky Way rising above a lightning-caused wildfire. Due to the fire’s isolation, the responding engine crew was inserted by helicopter and operated as a small hand crew, spiking out and monitoring fire activity in rugged terrain far from roads or infrastructure. After a long day on the line, the photograph was taken moments before sleep, revealing the rare and often unseen intersection of wildfire and wilderness. The image reflects the quiet, extraordinary scenes encountered while working fires in places few people ever experience.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026