Focus on Appropriation: Sydney Ellison

I first encountered the work of Sydney Ellison about a year ago and immediately was immediately blown away by the sensitivity and freshness of her images. The combination of writing, found images and family images is a recipe tried and true, and yet these images felt like things I had never seen before. I think Sydney’s work adds to a conversation that is so critically important right now. Questions of femininity and American Identity are central to Sydney’s practice, and through these questions, she grapples beautifully with the role image makers and image users play in today’s visual culture.

Sydney Ellison is a Brooklyn based artist whose work addresses themes of gaze and intersectionality primarily through collage and self-portraiture. Sydney is also a student at Pratt Institute and an editor for The Photographer’s Greenbook.

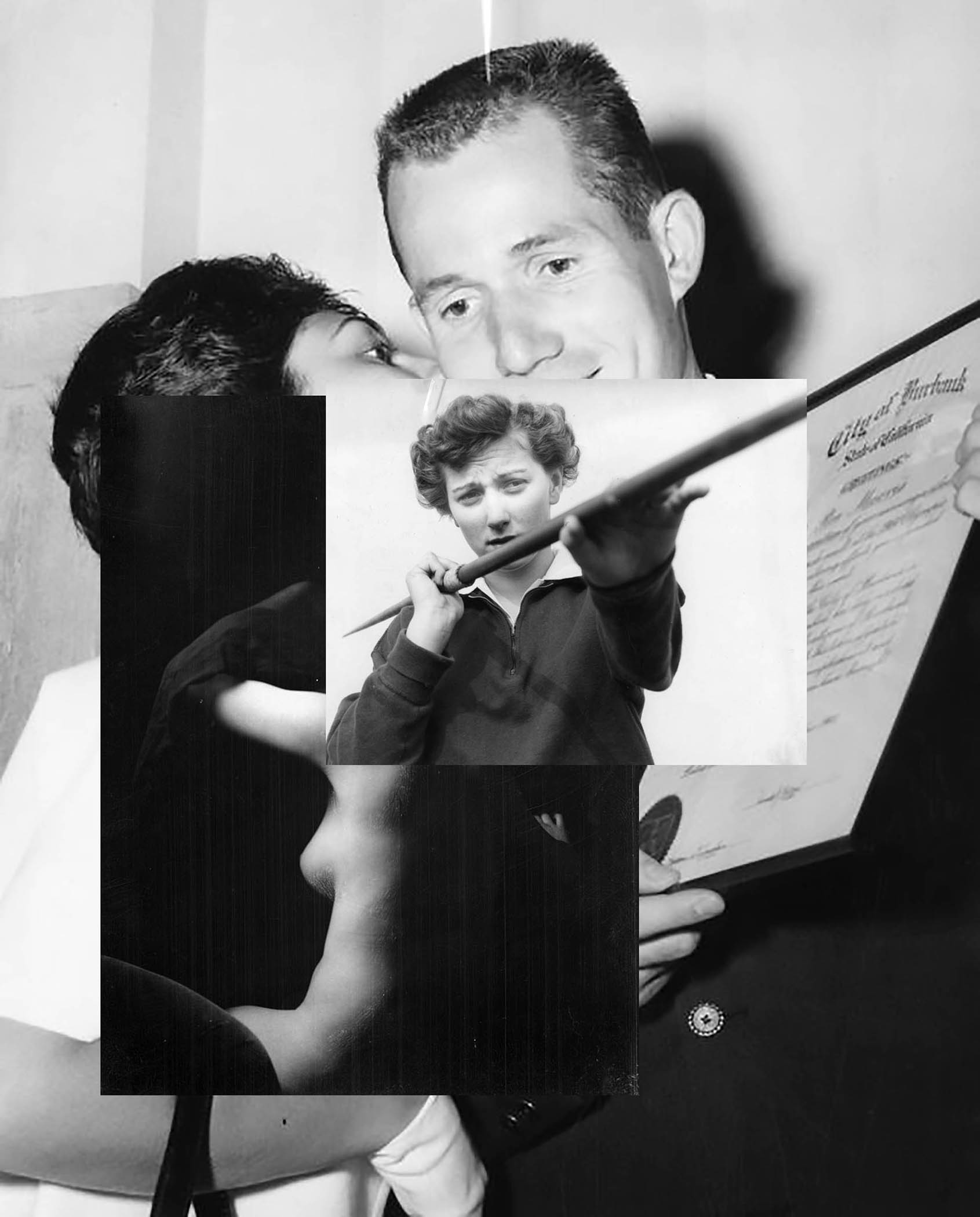

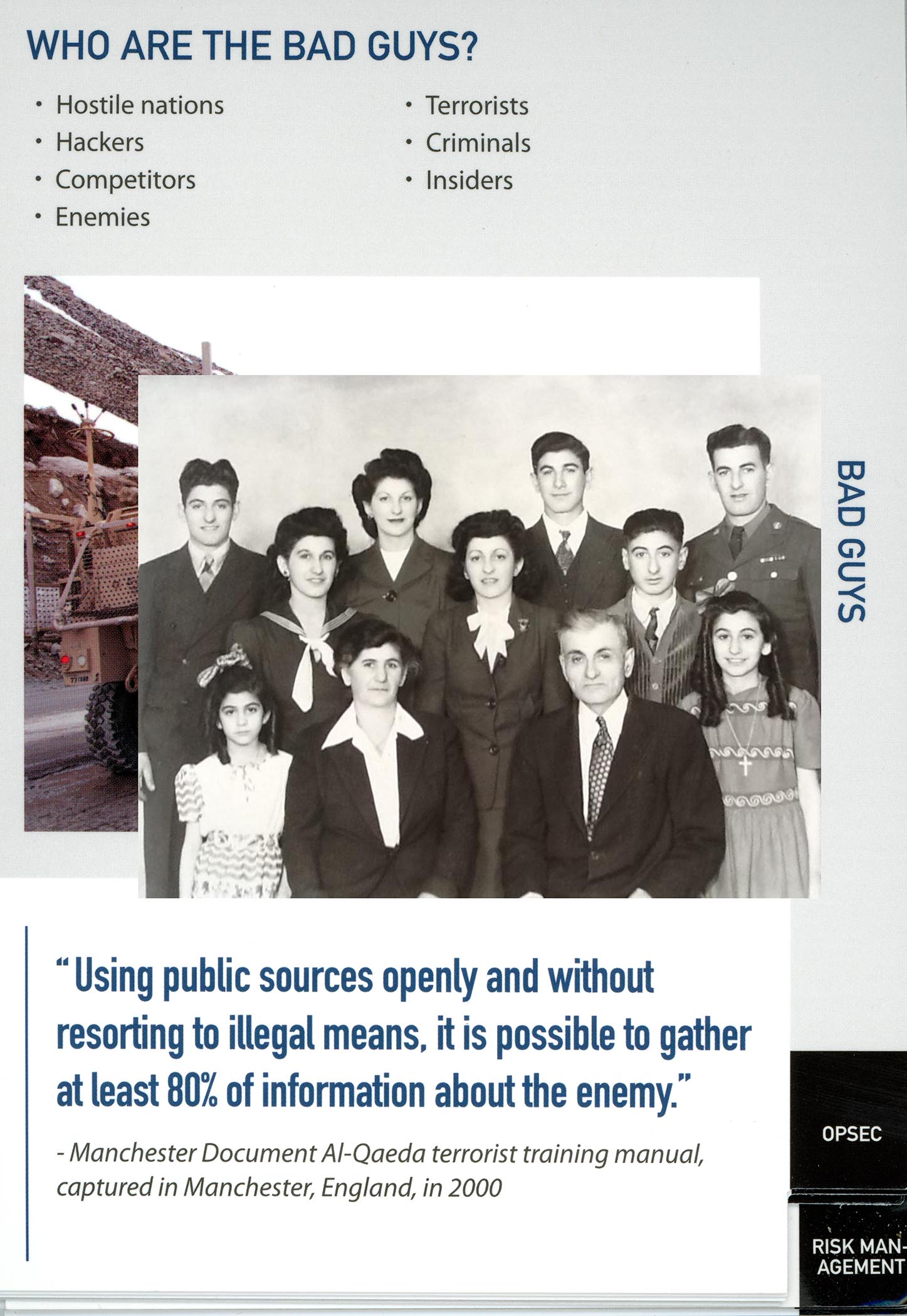

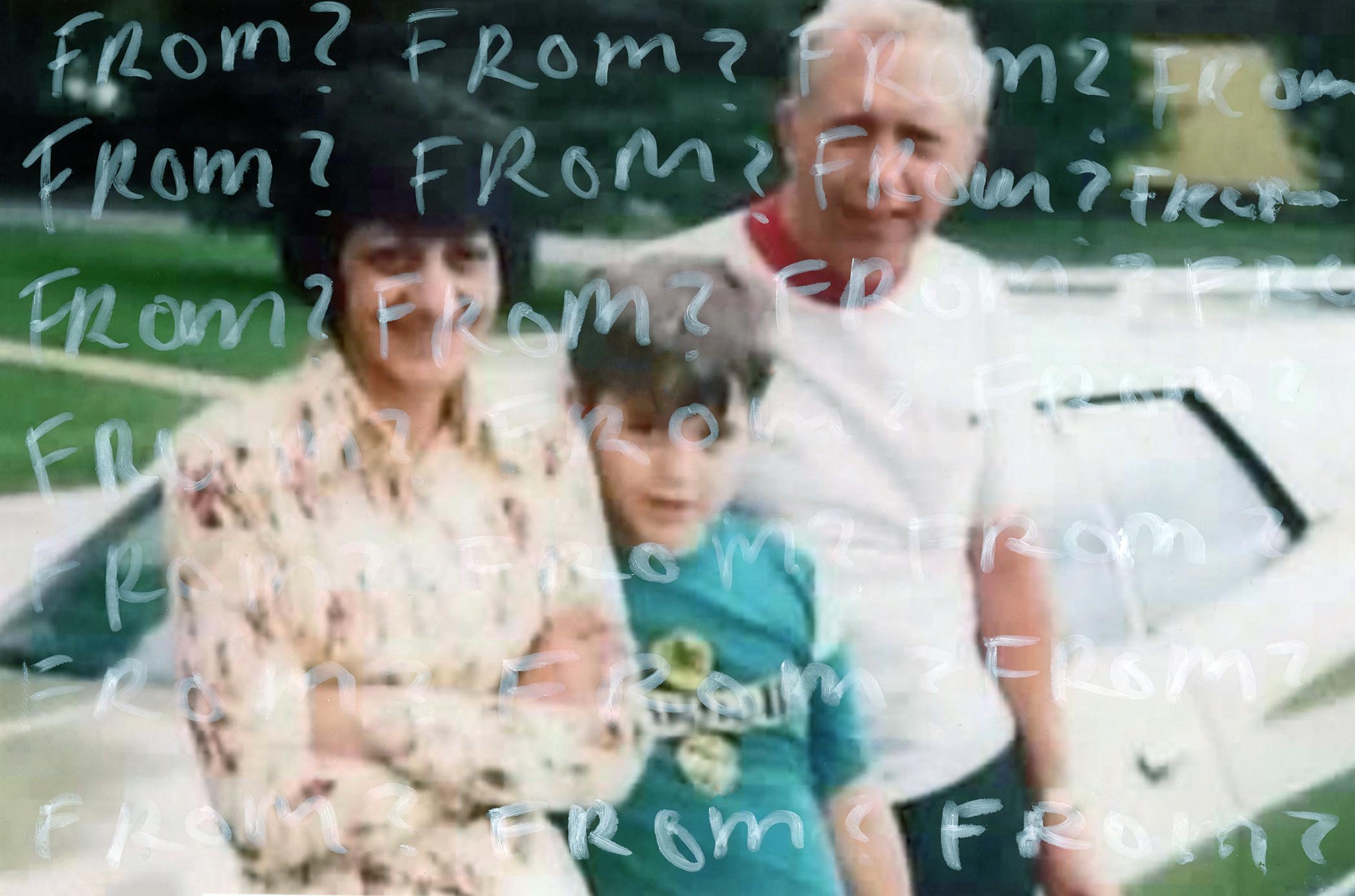

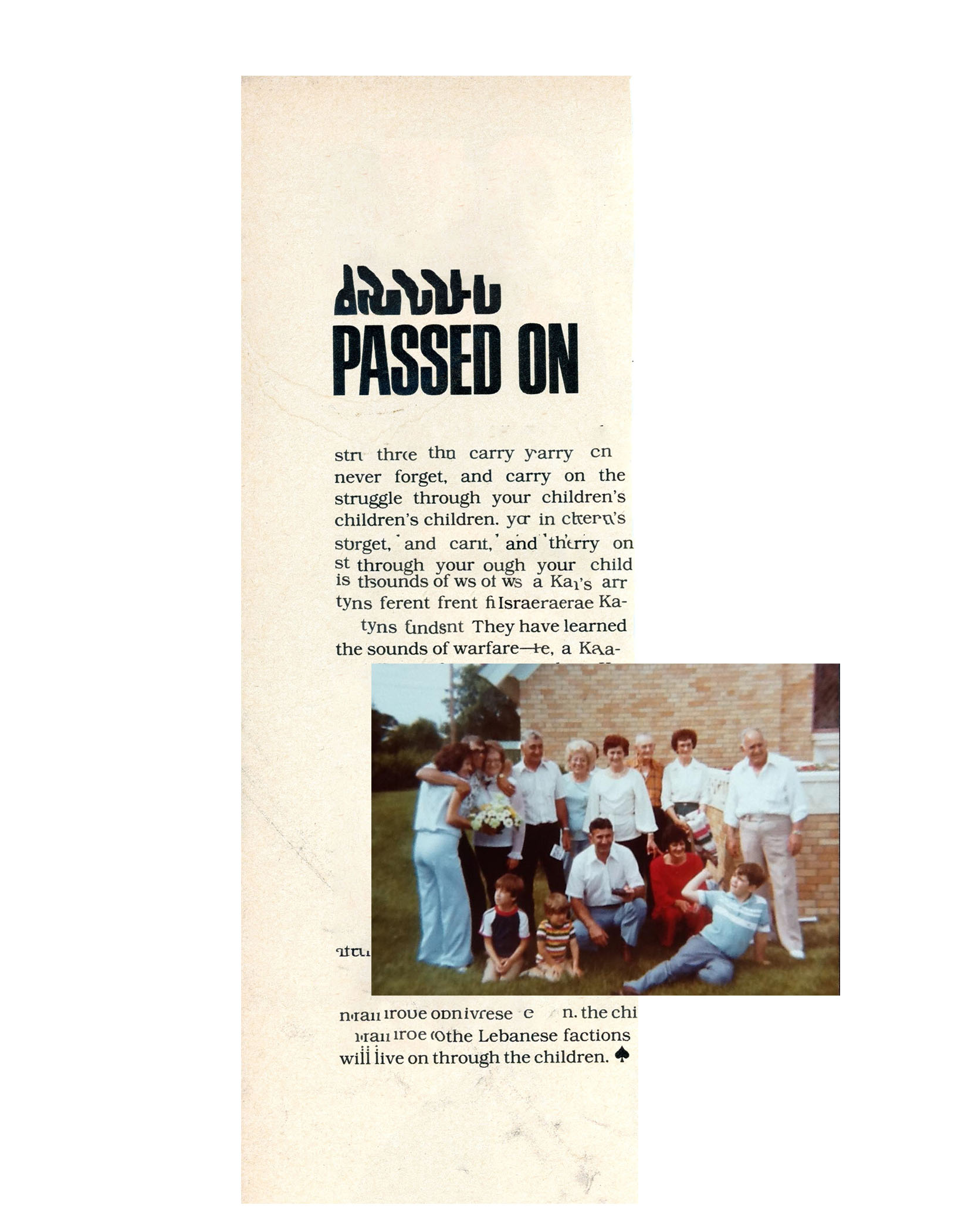

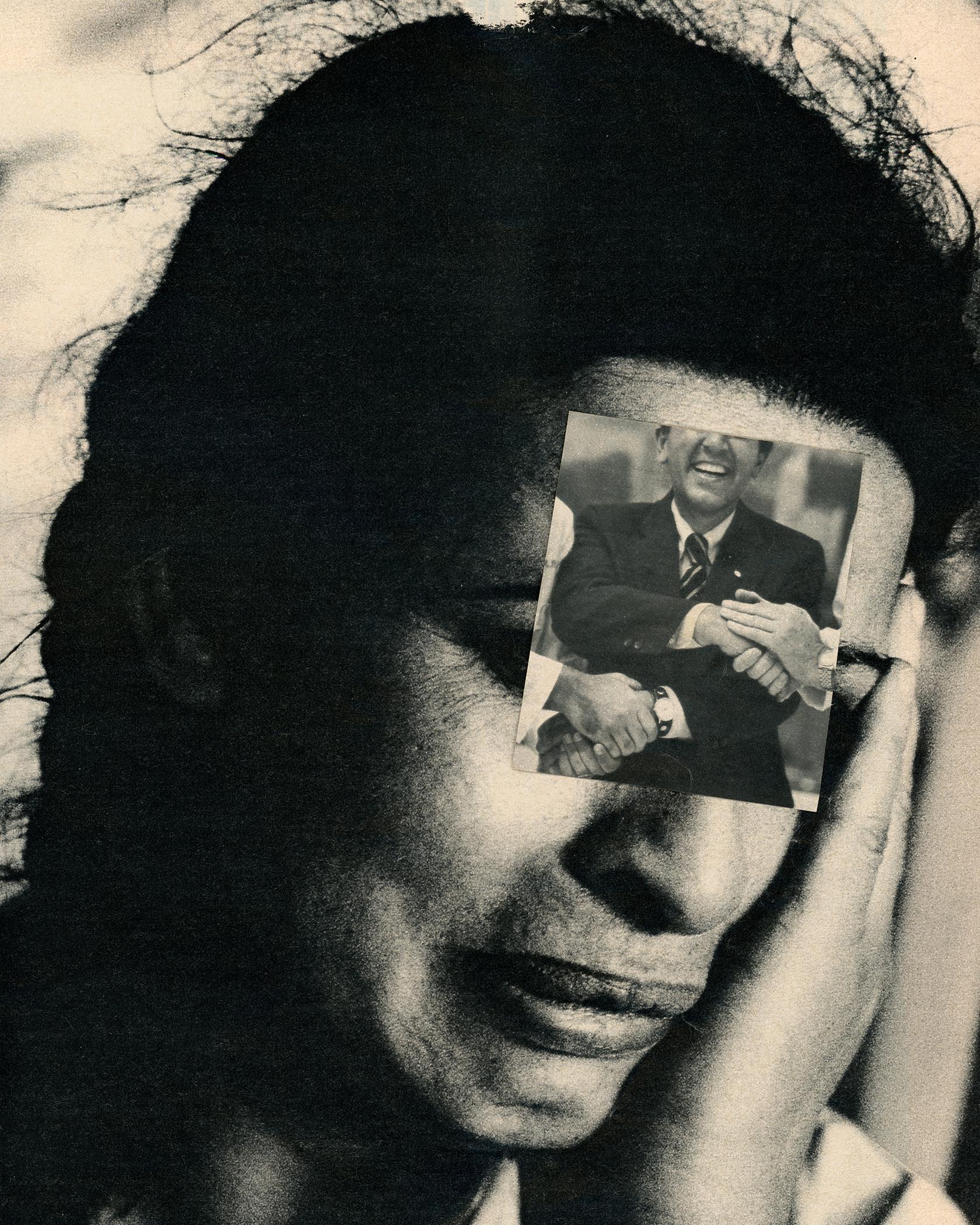

Here nor There uses collected imagery to explore intersections and gaps within American identity. Fragmentation and layering of imagery allow the artist to withhold and reframe existing materials as a decolonial tool. Furthermore, the fragmenting of imagery visually represents naturalization, intergenerational trauma, and ‘passing’ as they relate to how ethnic identity is experienced in the United States. The impulse to create this work comes from a lack of access to family histories, little to no accurate representation in mainstream media, and a desire to understand and archive the artist’s complex relationship with heritage

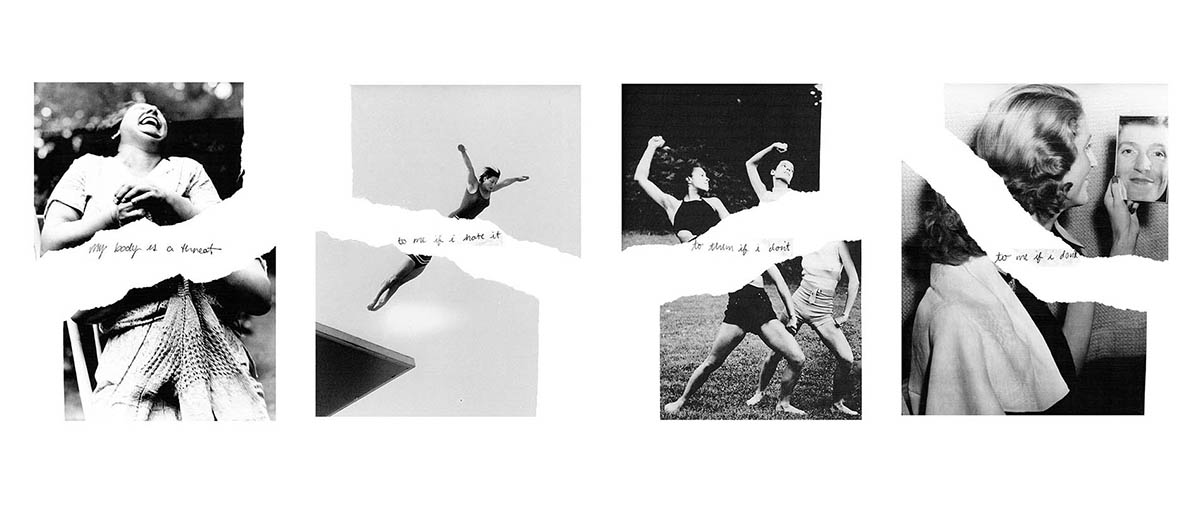

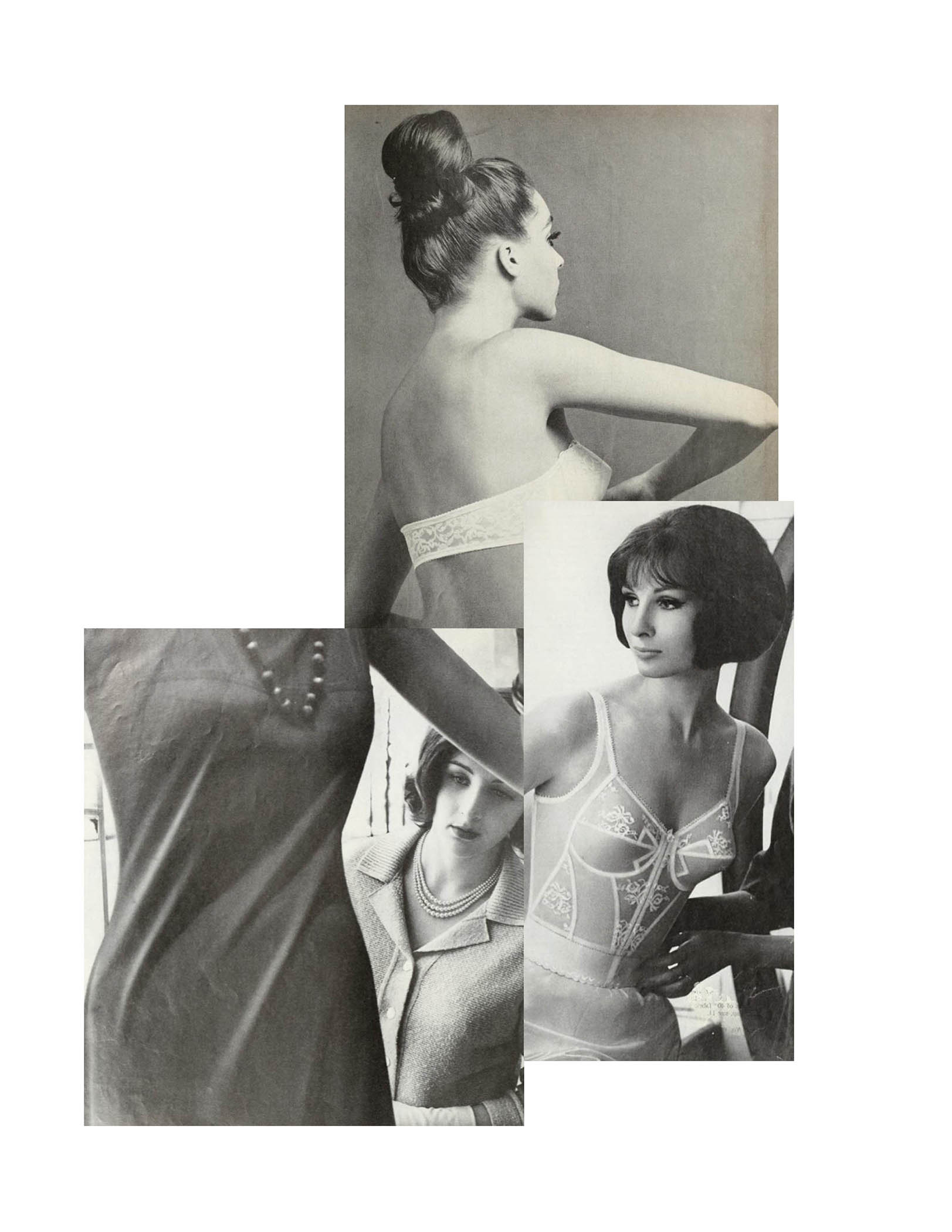

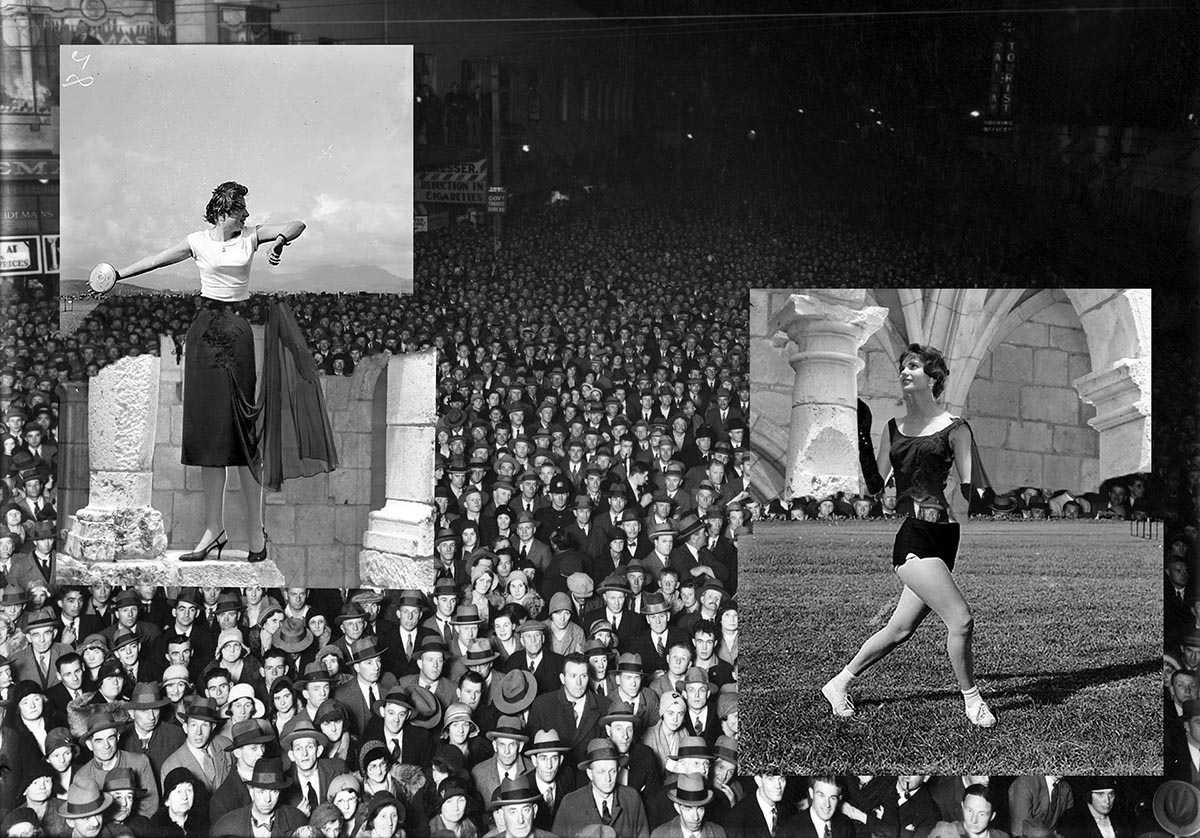

Her, again consists of collages, constructed from historical and pop-culture archival imagery, aim to address gaze, commodification, and agency as it relates to women and their bodies. The use of archival imagery is representative of the ways in which mainstream cultural memory and intergenerational indoctrination contribute to the socialization of gender and the erasure of opposition to gender norms throughout generations. Whiteness is pervasive throughout much of the imagery used as a result of the lack of representation of diverse women in American archival media, it also reinforces the fact that whiteness was (and is) yet another standard for many to women to contest with. I am interested in the way grouping images can help them take on a new significance and our tendency to believe what we see within the frame of a photograph as true. The images are layered or fragmented in order to produce a conversation focused on the socialization and performance of femininity. These pieces specifically focus on the contrast between activity and passivity and normative standards of beauty. Layering and fragmentation also direct the viewer’s gaze within the frame, adding to the sense of the images believably existing within the same space. The addition of text in these pieces relates to the artist’s experiences with femininity and is included to further direct the audience’s interpretation of the images in relation to their own experiences.

Brennan Booker: How did you arrive at the decision to use appropriated images in your work?

Sydney Ellison: I had been thinking about it for a while as a way to connect contemporary issues I was exploring to their historical contexts, but ultimately made the decision last March as quarantines were setting in in the US. I had been working on a project doing self-portraits in a studio setting and suddenly lost access to the resources I needed to make that type of work. Using appropriated imagery felt like a practical way to continue exploring issues that were important to me at a time when I had quite limited resources.

BB: Can you talk about the relationship between text and imagery you use in your work?

SE: I utilize text as a way to direct the viewer towards the intent of my work; sometimes this may be through short pieces of text that express my connection to the image(s), other times text is used as a way to complicate the way an image is read. In Here nor There there are a few pieces that use largely illegible text as a way of reclaiming, or at the very least complicating, existing narratives surrounding my ethnic identity while in the same body of work there are also pieces that use appropriated text and documents as a way of very explicitly connecting personal images to existing socio-political conversations.

BB: I’m really interested in your usage of images that are from another time. You and I are both relatively young artists, who really came to photography in the digital age. What is your relationship to utilizing the photograph as a physical medium, rather than a digital one?

SE: Growing up I didn’t have access to many physical photographs so I didn’t fully understand the impact that interacting with a printed photograph might have vs a digital one until I began undergrad and found myself with piles of prints I was making for class. At the time I began playing with layering test scraps from darkroom prints and was really struck by the ability to make new contexts for images just by placing them on top of or next to each other. This process of shuffling around printed photographs in order to create new relationships is more or less still how a lot of my work comes to be.

BB: I love the repetition of viewing in the images in Collage, whether it’s rows and rows of men, women looking in mirrors, or images of intense athleticism. What is your relationship to viewing these women and why did you choose to insert yourself this way?

SE: The repeating motifs in these images, for me, relate both to different levels of gaze and how the binary idea of gender is, and has been, socialized particularly in the United States. I relate to these women as representatives of ideals that don’t really affirm me but do provide context for the way in which I, and images of myself are received. I am interested in the ways our culture has covered up and watered down feminist and queer movements in the past which has created a sort of cyclical pattern of opposition to some of the same issues, from representation to division of domestic labor, decade after decade. I think my frustration with these cycles comes out through the repetition of these motifs. There are images that represent stereotypical, often toxic ideals of femininity that many of us have inherited but there also images that begin to complicate those ideals, images of athletes, and those that emphasize femininity as something that is performed.

BB: In Here nor There there are questions of identity, either removed or specifically asked for. How do you think about the connections between racial identity and appropriated imagery?

SE: I think a lot of artists exploring questions around racial and/or ethnic identity, myself included, gravitate towards appropriation of existing imagery as a kind of rebuttal against the ways that photography has historically been used as a tool of colonialism and white supremacy. Here nor There was started, initially, as a response to both disrespectful depictions of the Middle East in photojournalism I grew up with and the dramatic, blatant portrayals of whiteness I found when I began archiving photographs of and by my mom’s grandparents. Because the source imagery I’m using ranges from news imagery to family photographs, and from family photographs I’m protective of to those I’m hurt by, I definitely toe a different line between care and criticism depending on the power dynamics already at play in each image.

BB: Thanks so much for talking with me Sydney, I can’t wait to see how this work continues to develop!

SE: Thank you for having me!

Keep up with Sydney:

sydneyellison.com

@sydneyxx

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025