Maria Mavropolou: Image Eaters

“Filtered dreaming” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Filter bubble, a term that describes that the social media , search engine and other algorithms expose us to material that we are comfortable with, but is that actually a cozy place or a trap? What will happen if this bubble bursts?”

Maria Mavropoulou (b.1989) lives and works in Athens, Greece. She is a visual artist using mainly photography while her work expands to new forms of the photographic image, such as VR, LiDar scans and screen captured images. Her work and research focuses on the new realities created by the connectible devices and the contradictions between the physical and the digital spaces that we inhabit.

Maria holds a Master in Fine Arts and a BA from Athens School of Fine Arts. Her work has been exhibited in institutions and museums in Greece and abroad among which are Museum für Neue Kunst, (Freiburg, Germany, 2020), Miami Art week, (2020), 60th Thessaloniki International Film Festival(2019), Thessaloniki Museum of Photography(2019), Onassis Cultural Centre (2019), Athens Conservatoire(2019), Slought foundation (Philadelphia, USA 2019), Maison de la Photographie, (France 2018), Benaki museum(2018), Unseen Amsterdam, (Netherlands 2018) National Observatory of Athens (2018), Culturescapes Festival (Basel, Switzerland, 2017) SHED London (U.K, 2017) Athens Photo Festival (2016), Krakow Photomonth (Poland, 2016) Athens Biennale (2015) Mois de la photo, (Paris, France, 2014)

Follow Maria Mavropolou on Instagram: @maria.mavropoulou

Website: www.mariamavropoulou.com

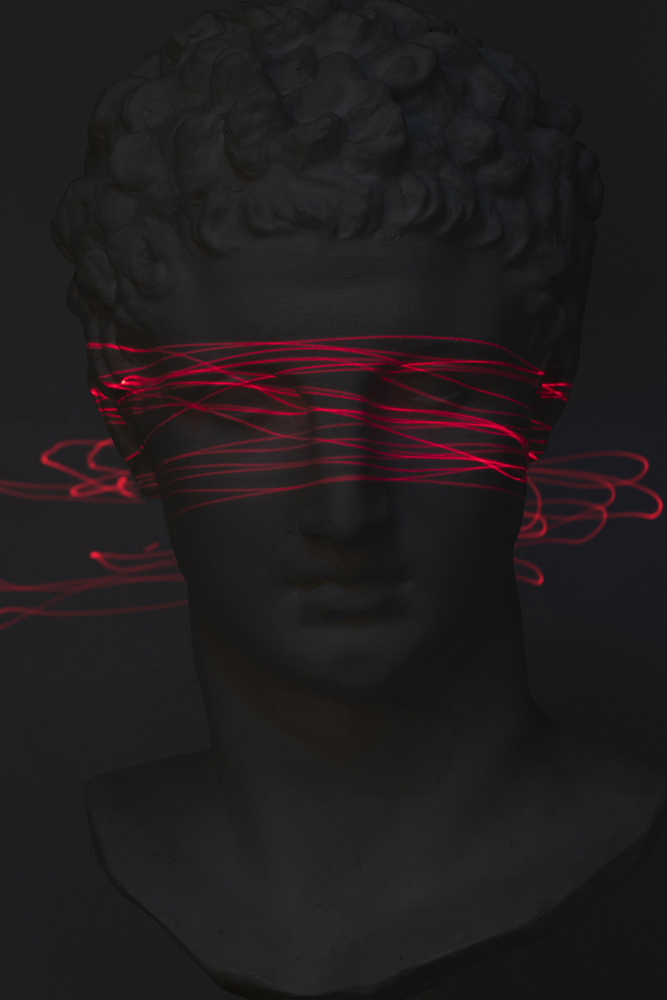

“Blind Folded” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Οur eyes are our guides in the digital spaces that we inhabit but at the same time they are constantly targeted in this attention economy. The over-exposure to stimuli that we experience may lead to some kind of “blindness”.”

Image Eaters

This series focuses on image making and image distribution in an era that is dominated by it while also questioning the bidirectional relationship between the creators and the distributors of images, humans and algorithms. The main idea came from the realization of a correlation between images and (!) food. Food is a basic need of every living creature, it is critical for its growth and survival, while images on the contrary are far from critical for our survival. I started noticing the vocabulary that is used for images, for example, on social media we call our endless image scroll “feed”, or we say “an Artificial Intelligence system has to be fed with images in order to be trained”. It became clear to me that there are a new kind of “creatures”, A.I.s and algorithms that do rely on images in order to evolve and thus survive. And since those intelligent systems and machines are in charge of more and more aspects of our lives, we too, depend on images as well in ways that we haven’t yet realized. In this new world where everyone of us is a set of facial landmarks, trapped in his comfortable filter bubble and where attention is the currency while our choices are more predictable than ever, is still the ability to think for our own fundamental? If not for survival then maybe to retain our human nature? Technology is constantly evolving and we get more and more dependent on images. This series aspires to question what an image is today while using images to achieve that.

“Pandora’s Box” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “This image was inspired by the myth of Pandora in relation with current image editing software. The white -gray checker is used to symbolize the transparency in editing software while mirrors are physical objects that only reflect what’s in front of them, so for me it was an experiment to blend the physical with the digital transparency and reflection in order to comment on the alterability but also the dual origin of current images.”

Vicente Cayuela: Your work reacts to novel methods of image production and concentrations of digital images unprecedented in human history. What made you interested in this topic in the first place?

Maria Mavropolou: My work is always inspired and informed by my experiences and the situations I live through. Technology started to play a central role in my artistic practice when I noticed that I was living in those digital environments more and more, when I realized that the screenshots were more than the actual photos in my camera roll! I had many questions about what these environments actually are and what different laws are governing them in contrast to the physical world so I started researching further on this topic.

Technology is not only the subject of my works but it also provides me with the tools I use to make my art. I’m always eager to see what more I can do with the tools that I’m using. I’m not using them just to create something different, I’m using them to understand how they operate and what they can do. I’m always trying to push further the limits of image making, whether I’m using still photography to create Virtual Tours, photogrammetry, 3D scanning, GANs (generative adversarial networks) or the latest text-to-image AIs. I’m also interested in how technology evolves because every new tool, every new platform, every new lens, every new update of our smartphone/camera gives us a different point of view to look at things.

It seems that the internet has become the infrastructure of the modern world, a world in which we have a different kind of identity, where our data and our attention are powerful currencies, where time and place have different coordinates. Our behavior is also different online. We post private moments and sometimes sensitive information that we wouldn’t share with complete strangers in the real world. Consider the cookies and the terms of use that we always accept. There are conditions we agree on without even reading them. Would you ever sign a contract without reading? We do it all the time! I was really interested to see the contradictions between these two different worlds that we live in and that are so intertwined that are nearly inseparable.

“The average of everything” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Facial recognition systems recognize our identity by translating our facial features to a set of dots- facial landmarks. Every human becomes just a set of dots and numbers in the machine’s eye.”

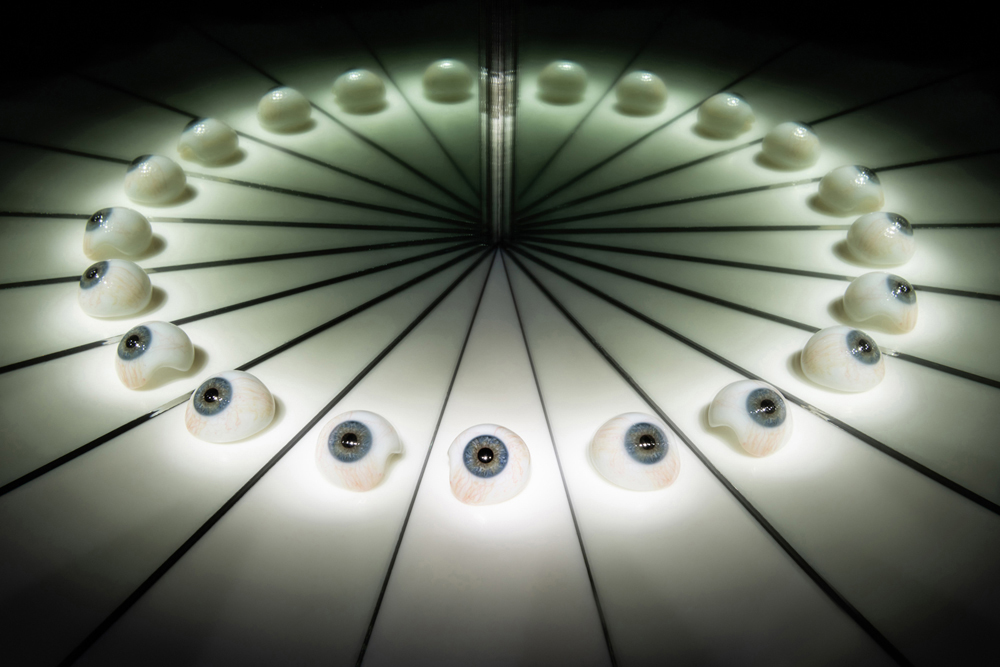

“Contact lenses” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “In the digital universe, everything we see has been captured by a lens of some kind of a camera in order to be displayed on a screen. What is visible is only what lenses can record.”

VC: Given the proliferation of AI or computer-generated images that look almost like photographs, what are your thoughts on the automation of art and its effect on photography? How do you perceive this human-machine creative relationship?

There is a vibrant conversation currently about how these image generating AIs may threaten artists and, in general, the creative sector. Even if personally I don’t feel that they could replace artists or photographers at this point, it is a fact that these AIs are very impressive and powerful tools that are getting constantly better. I guess painters would probably feel threatened as well by photography and it is true that some of them lost their job, but painting certainly didn’t “die”, instead it was freed from the constraints of representation and experienced a new, booming era. I wonder if today, when it seems that everything has been photographed, could these tools be a chance for photography to undergo a regeneration just like painting did? However, even if artificial Intelligence influences the fine arts in the future, it is still one more tool in our disposal. A tool that, surprisingly enough, seems to understand us and one that can surprise us with unexpected results and ever growing capabilities. A tool that nonetheless we need to get acquainted with at first and that operates best under the guidance of an experienced user. I tend to think of the usage of such AIs as collaboration. This is a new tool that has input of and access to all the art that has ever been created, all the images that can be found online. It has been trained on all what humanity has pictured to today. We are using this new kind of Intelligence to go further creating what we have in mind. We use words as lenses. We used to say that an image is worth a thousand words, but this relation has been reversed. Today just a sentence can create endless variations of an image. Maybe now a word is worth a thousand images.

“Looks Like Love” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “This image is a comment on echo chambers or even our “close friends” on social media, where views & likes are counted as affection, support and caring.”

VC: Your project statements really made me think differently about what images and these software are. I have to ask this back at you: What are we in the eyes of the machine?

MM: I don’t know what we are for them, how they see us. One thing I know for sure is that these machines, these algorithms need our data and our energy in order to function, to evolve, to be trained. So I guess they create a picture of us based on the data we have trained them to distinguish and evaluate. I like to say that we feed them with images and then they compose our feeds. We are their creators but they seem to be able to re-program us! How do humans and algorithms effect each other? What is the relation between us? It’s a bidirectional relationship of interdependence that is yet difficult for me to define in a sentence.

VC: The ethics of A.I. are a highly contested topic. You write in your statement that an “Artificial Intelligence system has to be fed with images in order to be trained.” A.I. can replicate our explicit and implicit human biases. Have you perceived any biases working with A.I. in your practice?

MM: There are biases in the real world so obviously they have found the way to the digital sphere too. Part of the problem is that we usually get to think that a program is somehow “neutral” so we are not always noticing a biased discrimination. The big tech companies are stating that it’s amongst their priorities to eliminate bias in their products, but do they really succeed in that? It’s nearly inevitable to proliferate the biases of the creators of those AIs since the wide majority of them are western white men. There are not enough people from other cultural backgrounds, people of color, women and non-binary people in these kind of positions. So of course, we still see the male gaze on how things should be. Artificial intelligence is not only proliferating but amplifying the biases that we are fighting against for centuries and the situation is becoming ever more disturbing as AI is given the responsibility to decide for crucial aspects of our life as job stability, safety, healthcare, finance and more.

“In the memory of others” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “We record our moments with such a rigor in order to share them with the world, but today’s images tend to be less the memory objects that they used to and more a proof of the moment they are referring to. They are displayed on screens, they emit light and vanish from view after a while, they are constantly moving and replacing each other in a never ending stream and then, they disappear. After their “moment” they live in our memories, physical or digital.”

“Login history” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “This image tries in a poetic way to co-relate our digital behavior and the belief that our faith is written on our hand’s palm in order to look deeper in our own existence. Who are we?”

VC: Can you give us a glimpse of your artistic process?

MM: It’s always different depending on the idea I’m working on. I should mention that I was trained as a painter. When I started my studies at the Athens School of Fine Arts I practiced painting for many years. I remember as a student in my first years that difficult confrontation with the white canvas and all the questions that it represented. What to paint? How to paint it? Why paint? What I want to say by painting this specific subject. Why does it matter (if it matters at all)? Even after using photography as my main medium and many other imaging technologies, I still have this white canvas and all these questions that come along in my mind before I start working on a new series. So it’s not about a fixed process, it is about trying to find the best method to convey a specific message that has artistic value as well. For example, I did a work in spring 2020, when the world was in lock down to talk about the notion of waiting and expectation, which was a series of impasto paintings (made with very thick paint) of digital loading icons. I took a sign that signifies the gap between digital spaces and brought it back to the physical world, during a time that felt like some kind of a glitch.

“Touch history” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Our every click is monitored, our every move in the digital space becomes valuable data for algorithms and their creators. We, the users on the other side, are left with a smudged, password protected screen. Our long scrolls, intimate conversations, guilty pleasures, formal emails and food delivery orders end up being an indistinguishable smear on a dark surface.”

“Paper, stone, scissors” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “A constant battle, the physical and the digital. The origin and the destination. Can there ever be a winner?”

VC: In “How to preserve an unflattering photo” you explore the idea that even if deleted, “digital images can still survive in inaccessible places.” Where are these inaccessible places? Do you have any thought on what they are like, or who truly has access to them?

Photographs are fundamentally different today from what they were used to be. They are not even of the same material anymore. They are ones and zeros. They are stored in machines, memory cards, servers. To a certain extent, they are invisible to us until the moment that they surface our screen and their data are translated to light patterns that we recognize. Photography used to be a printed piece of paper. You could burn it, you could hide it, you could give it away. If something goes online now, you lose control of it. It can be shared, copied, screenshotted, downloaded or saved on other devices. Even if you delete something from your own account, your chat or your email it can still be “alive” somewhere else, for example, in the servers of the company whose platform you used.

“How to preserve an unflattering photo” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Digital images are fundamentally different than analog ones. They are not a singular object, there is no prototype and it’s copies, digital images are code, a sequence of 0’s and 1’s they are stored in remote servers and in clouds. Every image, once shared can live forever, even if deleted, it still survives living in inaccessible places.”

VC: Thinking about the incredible access to images that humans and machines now how, how do you perceive issues around authorship? When a machine creates an image, who does that image belong to?

MM: Who do these images belong to is not really easy to solve and it is a highly debated question still remaining unanswered. I feel that, on one hand, these programs are functioning similarly to the way humans are. They see, they learn and then they compose new outcomes. Humans as a species always look back to preexisting knowledge in order to create connections on which to build new knowledge and be able to progress. At this point, all of human visual culture that has made its way to the digital sphere has been digested by the neural networks that compose the AI’s brain and is now likely to be shaped by words, available to be used in this new, exciting way. The achieved knowledge is called “ latent space”, that’s where information is stored by forming a multitude of dimensions that control every aspect of the generated image.

On the other hand there is the labor of millions of people that is utilized by a company without even asking for their permission to use their images in the training datasets and that in some cases charges the users for its products. The question of authorship becomes even more complicated when the AI is asked to create an image in the style of a specific artist, especially if he is alive and still creative. There is also the case of truly creative prompt engineering that takes time and effort to master, when the user inputs his ideas and guides the AI as a director in order to construct and refine the generated image.

Considering all those different ways that someone could use these AIs (and many more that I didn’t mention) I think that it’s very difficult to have an answer that would apply equally in all cases. Nonetheless, I guess we should first question ourselves if anything that we ever created has been absolutely unique, totally new or unlike anything we have ever seen before.

“All my windows” from Image Eaters (2021) © Maria Mavropolou “Screens and lenses, transparent objects, conveyers of images, the base of our digital civilization. Every part of the real world that we see online has been captured by some kind of lens and translated by code then projected on a screen. Those objects are the base of our digital culture.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Margo Ovcharenko: OvertimeJanuary 27th, 2026

-

Yumi Janairo Roth: EFFIGY 1462January 20th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025