Tamara Reynolds and Zach Callahan in Conversation with Ashlyn Davis Burns

I was so delighted to receive an email from Zach Callahan about a month after my second daughter, Stella, was born, inviting me to interview both him and Tamara Reynolds about projects they’ve recently shared with the world. Both because the newborn days can be an intellectual desert and doubly so as I had recently paused my Art Pursuits, but also because it brought me back to two artists I’ve followed for some time and two photographers who hail from the American South, which was a focus of mine in graduate school.

Zach’s new, self-published book Exhaust, is one I’ve seen develop over time, and I really admire how thoughtfully it has come together. The work depicts an often-overlooked side of Los Angeles from the perspective of a wanderer, roaming the dusty streets by foot, looking for connection in the midst of heartache. Tamara’s new work, which was exhibited recently in New York is a haunting document of a group of people living in eastern Tennessee who are referred to as “Melungeons” and have deep ancestral roots to many ethnicities including Africans, Native Americans, Europeans, Moors, Portuguese, Turks and Jews. They have claimed to be descendants of Phoenician sailors, Spanish explorers, shipwrecked Portuguese slave traders, survivors of Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony, a Cherokee princess, and even Mary, the mother of Jesus. In our contemporary context, they are an isolated community that has stayed together and stayed put, on land they’ve lived on for hundreds of years. Both projects present an aspect of America that is largely looked passed, if it is looked on at all, which gives these projects unique resonance in our current election year. Together, we discuss these works, how the two use the subjects they pursue to tell both a personal and broader narrative, as well as the uses and functions of photography in their practices.

Tamara and Zach, thanks for allowing me to speak with you both about your recent publications and exhibitions. Can you each give readers an overview of these projects—Zach, your self-published book, Exhaust, and Tamara, your new body of work that was recently exhibited at Chroma in New York under the title The Visitation?

ZC – Hi Ashlyn, thank you for taking the time to do this. Exhaust is a book that has been a long time coming. I started making these images right when I moved to Los Angeles in 2014, throughout graduate school from 2015-17, and then slowly adding to them until about 2021. I made several dummies along the way and in 2022 made a dummy that is the closest thing to what the final book became. The work is all medium format color photographs made in Los Angeles. When I first moved here in 2014, I was living in the valley on an air mattress in a friend’s spare bedroom. I didn’t have a car, but I did have a bike that I bought on Craigslist, so I spent about the first year or so I lived here biking around (mostly in the valley), just photographing as much as possible. I was fresh out of a break up, and at first I was trying to find a way to visually articulate my loneliness and kind of the loneliness of being in Los Angeles, which is a sprawling, isolating city. The more time I spent on my bicycle, using a combination of bike, bus, and train to get around, the disparity of wealth in this city really became clear to me, and I identified with the people at the bus stops, on the trains and on the street. Within that framework there is a certain type of person I am drawn to who is not an archetype, but is a character or person who I either see myself in or whose likeness represents something larger to me. The more I photographed, using the portraits and pictures of people as anchors, the rest of the images began to fall into place. I consider it primarily a collection of portraits and pictures of people that deal with the loneliness, disparity of wealth, and everyday moments seen on foot on the streets of Los Angeles.

TR – Hello Ashlyn, it is great talking with you and thank you for showing interest in our work. For several years, my partner and I had been traveling to his family’s home and surrounding area around Sneedville in East Tennessee. When he and I first met, like in the first hour, he randomly mentioned to me he was Melungeon. I hadn’t known of anyone personally being a Melungeon, but I was aware of their existence in Sneedville from a documentary that aired on PBS in the 90’s. I was intrigued. And with each visit, I became enthralled with this unforgiving landscape and wondered if the Melungeon people were still part of the community. I proposed to the Guggenheim Foundation my interest in documenting with my camera the people of Melungeon descent and the harsh land they lived on if they still remained.

For those who do not know what a Melungeon is, they are a tri-racial isolate. When asked by the pioneering explorers finding them already settled in the area of what was to become Hancock County, they claimed to be Portuguese. The Melungeon are not black or white or native, but their complexions run the spectrum from dark to light as well as red. They are considered to be from some of the oldest family lines in the country. During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, they were ostracized and demonized and eventually pushed off their fertile land along the Clinch River. They were finally left alone to eke out a living on Newman’s Ridge that overlooks the town.

Watching the resurgence of white supremacy and Nationalism in our country, I felt the story of the Melungeons was important to reevaluate. My wish is the project will encourage viewers to consider a complicated American history, the beauty of a hard existence, and a people descended from those who belonged but were never welcomed.

The Visitation

Reynolds brings an unflinching eye to consider what it means to be human, focusing on the lives of those who are often unseen. Her photographs “convey a sense of urgency…and open up new paths towards understanding the world,” writes Sarah Hermanson Meister, curator of the Museum of Modern Art’s photography department.

In “The Visitation” Reynolds turns her attention to the Melungeon, mixed-race Americans whose lineage stems from a range of ethnicities including Africans, Native Americans, Europeans, Moors, Portuguese, Turks, and Jews. With descendants who predated slavery, Melungeon family lines are among the oldest in the country. There is no agreement on the etymology of “Melungeon,” which has become a catch-all phrase for some 200 mixed-raced communities in the southern and eastern US. Since they were historically ostracized by whites, the Melungeon formed secluded communities in hard-to-access lands. Reynolds focuses her camera lens on one such place: Newman’s Ridge in Tennessee. She documents beauty and resilience despite systemic hardship, showing the perseverance of individuals, the community, and the natural- and built- environments that surround and sustain this Melungeon community.

In her application for the Guggenheim Fellowship which funded this photography project, Reynolds’ aim is to inspire “viewers to reflect on the very real amalgamation of the people that make up our country.” She recognizes the complexity embedded in American history and identity, and encourages us to reconsider “a people descended from those who belonged but were never welcome.”

Both of these projects deal intimately with overlapping notions of place and home for both of you. Zach, yours with the ever-present but often overlooked underbelly of your current home city, Los Angeles, and Tamara, yours with a historic group of people in eastern Tennessee. Can you each talk about the idea of home or community within these places as people not from here, but intimately linked to these areas?

ZC – My impulse would be to say that initially my work is actually coming from a place of not having a community or sense of home in this place, feeling like an outsider and gravitating towards similar types of people while photographing. I am not the kind of photographer who, like Tamara, will spend months or years building a relationship with a community and documenting people or patiently waiting for a magical photographic moment. There are a few subjects in the book who I had passing relationships with or photographed multiple times but that is about it. I respect people who work like Tamara, but that is not how I work. Something that intimately links me to the city is just the amount of time spent getting to know it in a way that most people don’t, which is on foot. While working I am probably only actually photographing like 20% of the time. There is a lot of time spent watching, waiting, walking, anticipating and being hyper observant of the people and things playing out around you. I don’t think many people really go out in the world and look at this city in this hyper focused way. There is an intimacy with the city and subject matter that comes from that. I think there is an inherent overlap in our work in that beneath the initial impetus for our photographs lies a subtle look at the issue of class in this country.

TR– It was within the first month or two of photographing that I realized many of the images I was gathering were homes. Sneedville is sometimes referred to as Overhome. I have been toying with the idea of using this as a title.

Two weeks before I began this project, I lost my sister to cancer, the second one in the span of 10 years. On top of grieving, I was having an existential crisis. I am the youngest of a big Irish Catholic family and I have been watching my immediate family slowly disappear. At the same time, I was building a life with Mike. His family and his family history became bigger in my life. Although I was grateful, I felt forlorn. It was as if my family was being replaced by his. I was desperately homesick, and I had nowhere to go with that feeling except out into the world photographing.

And while out in the Sneedville community, this notion of family was dominant. Most everyone was related in some way, or at least it seemed it to me. It underlined that feeling of being an outsider and emphasized my loneliness. Photographs I was returning with, as I mentioned earlier, were homes—homes from a distance with “no trespassing signs”, and impenetrable landscapes also with “no trespassing signs”. Eventually, photographs became more intimate as I immersed myself more into the project and began approaching people and exploring the area more exhaustively. At first portraits were of people in doorways that seemed to bar my way, appearing leery of me. I was anxious and lonely much of the time, but I leaned into it, trusting the process, relying on how this experience and encounters would shape the project.

My partner’s connection to Hancock County by family history became my entry point. Although Mike didn’t know anyone personally that I was meeting, his being from the area made me less likely to be rebuffed by those living in the community. As Zach mentioned earlier, I work differently from him, but I think we both use photography to connect to others and make sense of life conditions.

How does your own history play into the way you approached your subjects? And, was there anything you felt you were actively pushing against with regards to our shared Photographic History of ways of seeing and being seen?

ZC – I think all work is identity-based and the things we have been through in our lives, our history, our interests, likes and dislikes all form the way that we see. So other than the personal history I mentioned before of having gone through a break up, my childhood growing up in Florida shapes the way that I look at the world and the people I am drawn to. Having spent 8 years in New York City probably also affects the way I move through the world and there is probably a small part of growing up skateboarding that makes me feel very comfortable being on the street with no other purpose but to photograph. Having a background in literature and reading also informs my work. A lot of my favorite authors have written essays on the descriptive nature of writing and seeing and often when I read them I am mentally substituting the word “writing” for “photographing”.

Photographically, I feel like there were a few things I was really trying to push against but the main two were the photographic history of this city and the idea of street photography. Los Angeles has been photographed by many great photographers, several of whom I consider to be influences. It has also been depicted maybe more than any other city in the history of cinema (if you have not seen Los Angeles Plays Itself by Thom Anderson it is a must see). So I was both consciously and subconsciously trying to make pictures that weren’t overtly Los Angeles or the stereotypical Los Angeles we all know, while allowing just enough of it into the work to give it a sense of place. In general, a goal of mine is to always try and make an image that I haven’t seen before, which is becoming increasingly difficult.

I was also working against the idea of street photography, more specifically the athleticism, speed and democracy of 60’s-70’s street photography. My work is much slower, more deliberate, and contemplative than that kind of photography, but when you tell someone you are making work on the street you inevitably draw those comparisons and have to contend with that history. I just happen to live here and I think Los Angeles has a wealth of photographic themes to explore and the street is an obvious starting point because it makes up the vast majority of the city and there are the most people there. I don’t consider myself a street photographer.

TR – Being the youngest child of a large family, I learned to embrace being alone, not heard or seen. During those alone periods as young as 4 or 5, I spent time looking through Encyclopedias of Art my mother had in a corner hutch, in the dining room. The books I remember the most were the ones with Renaissance Art. The religious paintings were spectacular and beautiful, but also horrifying and violent. I knew I shouldn’t be seeing these things, yet I was seduced. Throughout my childhood, I spent many Masses gazing up at Jesus hanging way up there suffering on the cross. I was frightened and a little bit infatuated by this half naked man. It had to have some effect on me and why I feel a strange and complicated fascination seeking the beautiful in the harrowing.

About the time I was beginning photography and understanding its power, I took a literary history class where we read and studied fiction, poetry and drama. In one class we studied the poem by W. H. Auden, Musée des Beaux Arts. Auden uses Brueghel’s paintings, most particularly, The Fall of Icarus to discuss death and the indifference humans exhibit towards another’s tragedy. Auden writes that no one noticed or cared as Icarus plummeted to his death. Life carried on. I was deeply touched. I found that for me, photography remedied that idea of dying in vain or dying without having been seen. Chronicling life, others as well as my own, helps me come to terms with death and the emotions surrounding it.

In response to the Photographic History, I am more in step with traditional documentary photography. I am drawn to William Gedney’s work in Kentucky and Chris Killip’s in general. Both have a gentle response to humanity and life as it unfolds before the camera. My work is driven by exploring the complexities of life, the beautiful as well as the hard to see, the unexpected as well as the expected, the spectacular and the commonplace. Photography is my way to express my life and to witness another.

It is for these reasons I appreciate Zach’s photography. The photographs are a humble, gentle, contemplative record of everyday moments people experience. He gives us a peek into those lives and tacitly his own. And the photograph elevates those moments in this magical way.

Speaking of film and literature, would either of you say the stories you are telling resolve or lead the viewer to a specific conclusion? How do you view your role as a storyteller and how does the aesthetic approach you use relate to this? I’m thinking specifically of the very obvious relationship of visualizing California in color in a cool, detached way and the American South in black and white in a very intimate way, but also your framing and composition choices, which specifically position the viewer within your more conceptual framework.

TR – My work in Sneedville is about the people I meet, the life they lead, the land they live on. There is no resolution no different than life has a resolution. I am trusting that each photograph will guide me to the next. The story that may emerge from my edit will be a surprise to me. Life unfolds continuously and I’m simply going with it.

When I began the work in East Tennessee, I was seeing it in color. But in time, I began to feel as if I was living in a parallel universe. This is not a statement about the place, but something experiential. I want the work to express the emotions I was feeling moving through the environment. The choice of using black and white was to express another world (the light is magical there – the way it rakes across the land) and to enhance the feelings of anxiety and apprehension I was experiencing. I was scared but excited. I never quite knew what would emerge down a hollow or over a ridge, what kind of welcome or rebuff I’d get from a stranger, how I was perceived in the community. When I began printing the work, my aesthetic choice was to keep the blacks in the prints deep and hard to see into. I want the shadows to reference the mysterious origins of the Melungeon people, the secrets within the history of our country and to allude to my angst about being an outsider.

ZC – One of the things I like about photography is that it is an immediate abstraction of the world and people bring their own conclusions and reads to an image. That being said, I suppose the only conclusions that I come to in this work are that life can be lonely and unfair in this city/country, and there is a world separate from most people’s daily existence in Los Angeles that is there if you are willing to look. I don’t necessarily think of my role as being a storyteller in the way that there is some narrative in the work, but if we are comparing aesthetic choices to the way in which writers choose the way in which they want to describe the world with language (ie flowery and poetic or short and concise etc…) For me, photographing in medium format color is a way that I wanted to show people this place in an almost factual way, “look at this pink blanket”, “look at this woman with a wrinkled face”, “here is a dog tied to a fence with a ribbon”. So in the same way that Tamara was leaning into black and white for a sense of mystery and maybe slightly more abstraction, my formal and aesthetic choices were more about simplicity, accuracy and using the camera to do what it does best, which is to describe. I think the detachment you mention is a combination of this choice and maybe my own feelings.

TR – Doing what the camera does best! Love it. Although you are asking the viewer to look, you leave enough room in the frame for the viewer’s eyes to wander around in it, to discover things at their own pace. This is what I love about your work, Zach, and I so appreciate the subtlety, the lack of manipulation on the part of the photographer, the clear and direct perspective. I was watching a movie trailer just yesterday, I won’t mention the director (I was shocked, by the way), but the slow pan of the camera moving across the scene made me roll my eyes. I was like “PLLLLEASE”.

I’m also curious how you both see your work circulating in the world. Since we all come from such a deep photographic perspective, we know our community is small, and most of the work we do (as image makers, writers, curators, etc) ends up reaching beyond that small community fairly infrequently. From a professional and artistic standpoint, how do you reconcile this, and how do you attempt to give your photographs agency and access in the world? Is something missing in our community that might better support this?

TR – I lament as well as embrace the fact much of my practice is done for me alone. An important photographer/mentor in my life (she’s not aware of that title) once said when I asked her why she does what she does, (I was having a moment of doubt about being a photographer), her response was “I enjoy looking at my photographs”. Simple as that, period. I never thought about it, but I think that is why I am a photographer. I enjoy looking at my pictures, what I captured, how they line up to speak to me about life—my life and others’. But I have to say I also enjoy the experience of photographing—the people I meet, the places I explore. Photography fits my nature. As a child, I was a rule breaker, a risk taker, an adventurous spirit. Photography gives me the permission to continue being those things with a purpose.

I typically think about my work in book form because I love books of all kinds. And for obvious reasons I see the work as a book, because the dissemination of the work, the logistics of storage, the financial investment is not as challenging. The book makes the transference of my pictures wider. I am grateful to have had a show at Chroma Fine Art Gallery. I got to experience the prints big and hanging together, in conversation with one another in a new way. Working with prints on the wall was enlightening for me.

ZC – I really like what Tamara’s mentor said about enjoying looking at her own pictures. I do think first and foremost artists make work for themselves. If you have an audience for your work, you are lucky.

To answer your question, I think in the grand scheme of the art world or the world in general, the photo community is small and insular. The reach of our medium is almost trivial when compared to musicians or directors. There are alot of people in the art world with a capital A, that don’t understand photography or read images the way that photographers do. There are a small number of people who are the gatekeepers when it comes to getting work published or on a wall and if you are not a networker type or don’t have the money for some sort of photo retreat it can be hard to reach them. Giving your work agency in the world is a very difficult task and in a way can make a lonely pursuit feel even lonelier. That being said, for me, self-publishing has been liberating in that it has enabled me to take total control of when my book comes out, what it looks like, and how I want to distribute it. Additionally, some friends of mine and I just started an artist-run gallery space in Los Angeles called Seasons. Putting together our first show was very freeing. We were able to generate interest in our work and in the work of other artists we chose to include. Many artists and a few curators kept telling us “LA needs more spaces like this”. In a way it felt like instead of waiting for someone to pick you for a team or let you into the game, you can just start your own game that is just as legitimate. In short, it made me realize that one thing that is missing is more DIY/artist run spaces.

TR – I am glad you’ve brought up the whole DIY thing. Why put so much power in the hands of others? I will say that creating a platform for your own work is nearly a full time job. But it can be exciting too. Having places like Lenscratch is invaluable.

Thank you for bringing up the capital A art world not knowing how to read the photograph. I haven’t been in front of many curators, but the few times I have met with curators, I can tell when they appreciate photography. The questions asked, the statements made about what is in the picture, the language they use is inspiring. They get it. I could name a few that made talking and sharing my work with them worth me being a photographer. It was wonderful working with Rita Baunok, the curator of The Visitation for instance. She’s a photographer, she understands and loves photography, and she knows me. She respects my vision.

By the way, I am so very excited about Seasons. We need to take this on the road!

ADB – I agree with both of you, that we need more artist-run efforts. I think inherently ,the pursuit of photography is a fairly lonely one. It’s like writing in that it happens almost like an inner dialogue, rather than an external manifestation like painting or even music. Perhaps that’s one reason I’ve always been drawn to photography, as a writer and reader, is that it feels so deeply personal and there is a compulsory nature to it, the “I would do this for myself even if nobody ever saw it” type of need. I think it’s also a particularly challenging moment for photography because it has found a place in the art world, but as you both mention, it’s not a place that seems particularly well-understood by many critics and curators. It is a different language than painting or sculpture or performance because it uses the material of reality to shape its content, whether “documentary” or “abstract”. Then, there is the whole issue of truth that photography has grappled with from its inception and this issue of truth is an even more important one in our age of Artificial Intelligence, Fake News, and hyper-mediated content posing as fact.

What do you both make of these issues of truth in your own images and then how they sit in the larger cultural context of our current moment?

TR – As soon as I frame a part of the world within my viewfinder, I am conjuring. It is my bias, my truth that is captured. What is left out of the frame may give more context, but I’ve left all that out. And simply putting oneself into an event to record what happens before the camera influences the situation. Photographers arrange the chaos of the world into shapes, lines and textures to build a harmonious composition. They abstract an experience by using black and white film in the case of my project. This two dimensional world that the monocular eye of the camera creates is not what we see. Although I don’t play with the two dimensionality of photography purposefully, I do celebrate its ability to flatten the world I experienced at the time of capture. For instance, there is one image that comes to mind from this project where the subject is floating in water, but the tonal value of the water is so dark, it appears, at first glance, the subject is suspended above rather than floating on top. Of course, it wasn’t what I saw until I experienced it in two dimensions.

ZC– I like what you said about how photography uses “the material of reality to shape its content”. That’s one of the things that a lot of people get wrong about photography is they try to associate it with a document or truth. It is a type of document based in the material world and there is a truth, but it is never the truth. There are also so many subjective variables such as how the photographer was interpreting what they were seeing, what the viewer is seeing, what the viewer brings to their own visual literacy etc. One of my favorite things about photography, especially digital photography which is hyper-descriptive, is its contention with reality and realism. A reference I like to use is the sculptor Duane Hanson who made hyper-realistic fiberglass casts of people sometimes in scenes with other elements of the world such as televisions, trash cans, rugs etc. When you remove these things from their context of real life and allow people to spend time with them, they can take on so many different meanings.

As far as my own work goes, I would hope that there are truths in my images, but I don’t consider any of them to be the truth or to be a mirror of reality. They are fictitious renderings of reality based on how the camera describes the things and people I am interested in. Regarding the second part of your questions and how that relates to the current cultural moment—the language of photography you employ affects the way people read your images and their relationship to “truth”. The language I am using sits outside of what is the most ubiquitous language and one that people accept as truth these days, which is imagery and video made on cell phones. Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death, is a good example of a piece that uses the power of that language and of perceived objectivism, realism, or truth to subjectively critique.

EXHAUST is a collection of medium format color photographs made between 2014-2021 in Los Angeles, California by Zach Callahan. Through a contemplative and empathetic lens the photographs examine what the social landscape looks like for people navigating the dusty streets, public transit hubs, and sidewalks in a city notoriously dominated by car. The work primarily consists of portraits of working class outsiders and quiet everyday moments amidst the whirr of traffic.

Both of these projects were long-term for both of you and my impression is that the process of working with the images after shooting had as much of an impact on the final work as did the making of the pictures. Tamara, did you know upon receiving the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship what the shape of this project might look like? How has it evolved from concept to execution and now presentation? Similarly, Zach, with the book, did anything change for you in the editing process of putting together the book? Do you feel the photographs operate differently when presented singularly than they do together within the beginning and end of the book form? Did you always know you wanted to publish these as a book?

ZC – Editing images is probably the only thing as hard as making them. The book is only 36 images, so yes, I was working with the images for a long time after making the pictures. I think something that changed for me was my own relationship to the images. I haven’t stopped photographing in Los Angeles but for me I felt like it was important for these images to come out as my first book because I feel like I am a different person now than the person who made those images. For me it is like discovering a band, you might hear a song that you like and then you inevitably want to go back and listen to their first album to hear where it all started and how their sound changed and grew—I wanted this to be my first album.

It is also interesting that you ask about thinking about the images singularly, because I do often think of images that way. Some of my favorite photobooks are more like catalogs of very strong singular images rather than some sort of long term project (although there are of course many long term projects that I love). I don’t think Walker Evans ever felt like he was working on a long term project when he was making his work, it came together as the book afterwards and that is how I kind approach making work here in Los Angeles. Editing and sequencing was difficult and in the end I chose the images based upon their aesthetic similarities and the tone or feeling of the images. I sequenced based on color, form, and other subtle relationships between the images.

I did always know the work was going to be a book, but only because that is the most accessible way for people to get a hold of your images. I have to say I much prefer going to a really good photography show rather than looking at most photobooks because you can make the images larger, the relationships between the images and sequencing doesn’t have to be as rigid, and you can use distance and scale to change those relationships.

TR-My practice is all about long term. When I began the work in Sneedville, I knew the Fellowship year was going to be only the beginning. I had a framework when I presented it to the Guggenheim Committee. I had a place, an entrée, a concept, but I had no idea what I was going to find. And I did not want to box myself into a result. Like I mentioned previously, I wanted the work to be experiential. Early on in the work, I was guided by someone I respect in the field to not go out and “check the boxes”. So, I purposely did not look for answers to any questions, or confirm expectations. I was seeking something of a mystery and I wanted to keep it that way. I now strive to have my practice about finding the questions, not finding the answers.

Photographs operate differently when presented singularly than when presented with another photograph or groups of photographs. Like reading a beautiful written sentence, photographs can operate similarly. When I look through photo books, I’ve learned to read them like a novel, history book, bio, what have you. The books I enjoy the most are when the photographer comes into my consciousness and then recedes. Then as the viewer I come into the work. It is kind of a dance with the artist, the subject and myself as the viewer.

ADB – ”I now strive to have my practice about finding the questions, not finding the answers.” I love this sentiment, Tamara. And, I think most of the art I admire does precisely this with a mission. It’s not as vague as “take from it what you will” (which is a huge pet peeve of mine since every artist is the master of the perspective they present) but moreso, “look at this place, idea, feeling, etc you otherwise wouldn’t have looked at, and look at it from my perspective.” Perhaps it’s more like a song or a poem than a story, though I also think many great stories don’t resolve either, but rather leave us with a question, an impression, or an emotional meandering.

TR – One of my favorite books is Blood Meridian for this exact reason. I finished that book on a Friday night and began reading it over on Saturday morning.

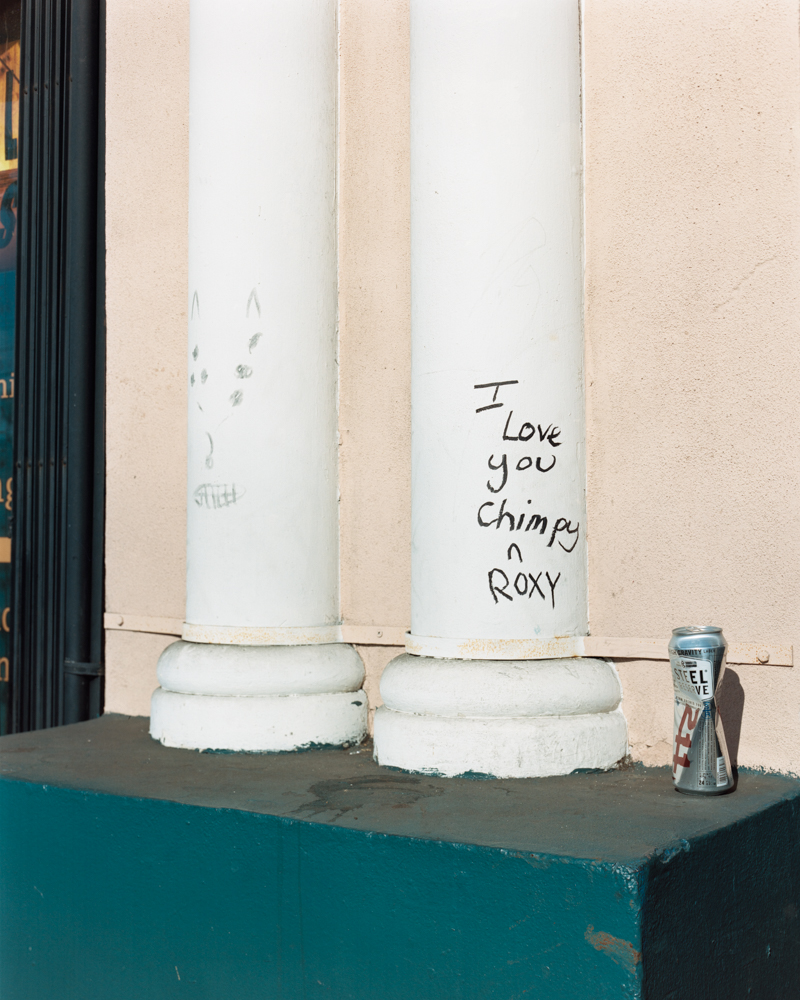

ADB – Zach, for me, when I sit with Exhaust, I get a feeling of a long moment of futility. I think we all have those moments in our life—where it feels like things don’t quite add up and we wonder if they ever will…if this moment will lead us to something greater or at least more comfortable. And, you give us these glimpses full of tension. For example, the image of the crushed can of Steel Reserve next to the classical column half jutting out from a wall with, “I love you Chimpy n Roxy” written on it. Perhaps there is loss but at least there was, there even still is love, even if it’s crushed like that can. How did you seek out these moments? Or, did they reveal themselves more so in the editing process? Did it come from a more intuitive place, or did you truly seek them out?

ZC – The “Chimpy n Roxy” image you’re referring to is a column I would drive by all of the time and was thinking thank Chimpy n Roxy could be a number of people (or dogs) in the work. There were always lighters, frayed phone charging cords, and other detritus around that column but the one day I went to photograph it there was nothing so I actually put that can of Steel Reserve there. In a way, getting out of my car to photograph that column is what the entire book is about in that I got out of the car to look at the world, which most people don’t do here.

Futility is maybe one of the more accurate interpretations I have heard anyone use when describing what they see in this work. Yes, there is an underlying tone of futility or heartbreak in this work. That is something I was dealing with. Though I have changed and my life is in a different place since making this work, my general worldview was and can be pretty cynical/critical. I think that is why I tend to gravitate towards the kinds of moments and people I do and photograph them in a way that is slow and deliberate and ideally leads to a contemplative read. In a way I was attempting to say yes, the world is tough and unfair, but here are these people and moments that I find worth looking at and maybe some of them look and feel like they are going through the same thing I am going through.

I don’t necessarily seek them out in order to illustrate that feeling, it is more intuitive, both in the photographing and editing phase for this work. That is something that is very challenging about photography, how subjective do you allow yourself to be while also trusting that the camera’s objectivity will serve you without being illustrative of your ideas, concepts, or emotions.

TR – I want to touch on this notion of singular images coming together to tell a story in the end. I think that if we are true to ourselves, we will find a thread in our work that continuously resurfaces. We are drawn to certain things and we have a sensibility that shows up time and again. We all have been informed in life uniquely, and we in turn interpret that life uniquely, then we transmit that life uniquely. With that said, I photograph with the single image in mind, then as the edit takes shape, as the work builds, depending on the parameters of the photography, the edit may begin informing the single images. But it depends, like Zach mentioned. The making of the work and the edit of the work is independent of one another. Either way for me, I must trust the process that I outlined above. Something of me will emerge. What the work is going to be about may be different by the time I publish.

ADB – Tamara, I want to return to the influence religious iconography has had on you. You said earlier, “I knew I shouldn’t be seeing these things, yet I was seduced to look.” I can’t help but think of Richard Misrach, showing us the beauty in horror, enticing us through color and composition to sit with something quite disturbing or terrible. It’s interesting to think of religion in this context, and really the whole of life, which in my experience is a co-mingling of astounding beauty, gut-wrenching pain, confusion, serendipity, grace, and the bore of the mundane. And, I can’t help but think of the image from this project of a still life where The Last Supper–just a third of it–hangs above a sagging, hand-made shelf of shelf-stable foods–canned green beans, condensed milk, peanut butter. There is what I see as a bedsheet, hung from the ceiling, acting dutifully as a draped cloth in a classical painting, wood paneling that seems to be not made of wood, a candle sconce with no candle, a bowl of lemons next to a carafe of sunflowers in relief, hung crookedly where more disciples would be. This image is full of so much contradiction and tension, but it also feels super practical and even intimate. Can you talk more about this image?

TR – I grew up celebrating the Last Supper in the masses I attended. This is a painting that many Catholic kids are very familiar with. So this painting holds a lot of power for me. Also, it is often typically found in kitchens in modest homes. This was the first one I saw cropped in such a way hanging in a food closet with neatly stacked food cans with one precariously balancing on the edge of the table. The setting was packed with meaning. I had to record it to show who lived there. Also, I am often influenced by other artists’ work. For instance, Mary Frey has an image in her book “Reading Raymond Carver” that shows a group of women with children at a kitchen table sitting under this da Vinci painting. That photograph of hers is seared into my brain. I wanted to pay homage to her, although she uses the painting to say something different in her photograph.

ZC – I love this picture and when I see it I am reminded of how differently we probably work. I don’t know if this picture is in a church or in someone’s basement but I feel like it is the kind of image you can only make if you work like Tamara spending a lot of time with your subjects and gaining access to their lives and homes, which is maybe the intimacy you are describing Ashlyn. This doesn’t relate to religious iconography per se, but this is also the kind of photograph you make when the photo gods present you with a gift.

ADB – And, thanks be to the photo gods! I think you’ve both captured these overlooked people and places in a way that situates both within these locales or communities, but also within your own feelings, where what appears before the camera is perhaps more about yourself than even what you describe. That is one of the blessings of photography – to do both simultaneously, looking both outward and inward through the language of reality. Thank you both for sharing this work with me and the Lenscratch community.

Ashlyn Davis Burns is an independent curator and writer based in Houston, TX. In 2021, she co-founded Assembly, a gallery focused on contemporary art and lens-based work, which is still being run by co-founder Shane Lavalette. Prior to that, she was the Executive Director and Curator at Houston Center for Photography from 2015 – 2020. Currently, she serves on the board of directors of FotoFest and the Advisory Council of Houston Center for Photography.

Instagram: @ashlyndavisburns

Instagram: @assemblyprojects

Tamara Reynolds is a documentary photographer whose unflinching eye considers what it means to be human in today’s society. In particular, her work focuses on the lives of those who are usually unseen.

Reynolds’ photobook The Drake was published and released by Dewi Lewis in early 2022. The work — portraits, still lifes and streetscapes that document the lives of people existing just above survival on one square block around a motel in Nashville, Tennessee — has received numerous honors, including a 2024 Puffin Grant, 2021 Guggenheim Fellowship, the 2021 BarTur Photo Award, a 2020 Puffin Grant, the 2019 Tennessee Arts Commission Individual Artist Grant and the Santa Fe Center 2018 Project Launch Grant. Reynolds’ acclaimed earlier body of work, Southern Route, which explores issues of identity, conflict and the disappearing culture of the South, was included in Southbound, a traveling exhibition and book curated by Mark Sloan and Mark Long of Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art.

In 2017, she received a Master of Fine Arts from the University of Hartford, where she graduated with honors. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Middle Tennessee State University where she was recently inducted to their Wall of Fame.

Prior to her current work in documentary photography, Reynolds has worked as a commercial photographer for over 30 years. Her work has appeared in many national publications including New York Time, NBC News, Bloomberg Businessweek, and The Guardian to name only a few and has been part of numerous national advertising campaigns.

Tamara Reynolds was born in Nashville, Tennessee, and has lived there all her life.

Instagram: @tamarareynoldsphotography

Zach Callahan (b. 1984 – Gainesville, FL) was raised in Jupiter, Florida. In 2006 he received his BA in English Literature from the University of Central Florida and soon after moved to New York City. He earned his MFA from the University of Hartford’s International Low Residency Program in 2017, where he was awarded the merit scholarship. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California where he has held adjunct positions at Cal State Long Beach and ArtCenter Pasadena. In August of 2024 he self published his first monograph Exhaust. The work examines class, loneliness and quiet everyday moments on foot in the streets of Los Angeles, a city that is dominated by car.

Zach is also a founder of Seasons, a Los Angeles based artist-run platform for contemporary photography. Its programming includes exhibitions and publications that exist in physical and digital spaces. The inaugural show was August 3rd, 2024.

Instagram: @zachcallahan

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Interview with Dylan Hausthor: What the Rain Might BringDecember 23rd, 2024

-

Kathy Shorr: LimousineDecember 12th, 2024

-

The New Renaissance of Photo BooksDecember 7th, 2024

-

Chance DeVille: Growing Tired of Calloused KneesDecember 5th, 2024