Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American Gulag

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “Going to the detention center was really difficult. Her appearance had changed drastically. Her long, beautiful, jet black hair was gray. Her chubby cheeks were reduced to bone. Her beautiful smooth face was filled with wrinkles.” Tania, youth organizer with the Community Immigrant Youth Justice Initiative Alliance describes visiting her mother in Mesa Verde ICE Processing Facility in Bakersfield, CA. Photo: March 2018

The scale and scope of U.S. immigration detention system and the trauma it inflicts on thousands of people each day is staggering. Greg Constantine has created a multi-year project that uses multimedia and ethnographic methods including over 200 hours of testimony to highlight the psychological impact of the U.S. detention system, which is the largest system globally. “7 Doors: An American Gulag” visually documents over 70 U.S. immigration detention facilities across 25 states through photographs and interviews of former detainees and their families. The project portrays the deportation-industrial complex’s erosion of due process for non-citizens, exposing the trauma and human cost of administrative incarceration. Constantine has been awarded the 2026 Bertha Challenge Fellowship by the Bertha Foundation in the UK and will spend the year expanding upon the work. His investigations come at a critical time in history.

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, A bus from the Pinal County Sheriff’s Department drives away after dropping off detainees at the Eloy Immigration Detention Center in Eloy, Arizona. Photo: April 2018

For several decades, immigration detention has been a central component of immigration and asylum policy in the United States. Today, over 65,000 immigrants are detained each day in the US in an expanding web of prison-like detention centers, state prisons, county jails or other facilities. Media coverage and policy discussion of immigration have historically been defined by the politicized optics of southern border crossings. While attention has shift over the past year to the interior of the country and the actions of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a significant and much more entrenched institutional component of US immigration policy remains unexplored: the US immigration detention ‘system’.

Moreover, the visual translation of the use of immigration detention and this system continues to be reduced down to info graphics or illustrated maps. But how much does the US public really know about the scale and scope of this system and the trauma it inflicts on people?

For almost a decade, I’ve traveled to nine countries as part of a long-term project called Seven Doors. The project investigates and documents immigration detention systems around the world. The United States is the centerpiece of this entire project. During Trump’s first term, I made almost ten trips, crisscrossing the country in my car, traveling over 40,000 miles. Through images, data/statistics, voices and oral testimony and video, this work interrogates the widespread use of immigration detention in the United States in an attempt to demystify and expose: where these places are located, what they look like and how they traumatize and damage the lives of individuals, families and entire communities.

My work in the US titled, An American Gulag, presents a multi-layered ‘photographic atlas’ of the US detention system. Photographs of larger detention centers along the western, southern and eastern border and of county jails throughout the interior of the US are paired with oral testimony of individuals sharing their experience in these facilities. Voices and audio testimonies of those who have been detained, families who have someone in detention, of immigration lawyers or of those trying to help people in detention serve as guides into this experience. I feel it is an immersive way of transporting people closer into the lived experience of what life is like inside these places of injustice. Documentary work and short videos are used to further ground the work and also share personal stories and the efforts being made to combat this system. In parallel with the visual work, data and statistics are used throughout to add more context.

The use of detention reached historic levels during Trump’s first term, and the Biden Administration failed to significantly reduce immigration detention. However, the Trump administration’s second term has already shown how America’s immigration detention complex will expand exponentially over the next three years. In 2026, I will continue and expand this work while also adding new layers of visual reporting. – Greg Constantine

Website: www.7doors.org

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “My family is from Vietnam. When my father reported to immigration, ICE arrested him. We had no idea. It was a total surprise. He was in detention for months. We paid the huge bond and were told he would be released so we drove down from San Francisco to pick him up.” Daughter of man being released from detention at US Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles. Photo: March 2018

Greg Constantine is an American/Canadian documentary photographer and author. He has dedicated his career to long-term, independent projects that explore themes of human rights, inequality, citizenship, identity, genocide and the power of the state. His award winning projects include: Nowhere People, Exiled To Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya, Kenya’s Nubians and Ek Khaale: Once Upon A Time. He is the author of three books. Solo exhibitions of his work have been held in over 40 cities and his work has been published widely around the world. He has been selected for exhibitions and screenings in Chobi Mela, Angkor Photo Fest and Visa pour l’Image. In 2017, he was awarded his PhD from Middlesex University in the UK and has since received fellowships from the Independent Social Research Foundation and Queen Mary University in London. For the past 10 years, he has documented systems of immigration detention in several countries around the world for the project Seven Doors. His expansive work on immigration detention in the United States titled, An American Gulag, received CENTER’s 2025 Multimedia Award. Constantine is a 2026 Bertha Challenge Fellow.

Instagram accounts: @grconstantine @immigrationdetention

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “They put this bracelet on me the day I was let out. It hurts when I wear it. It still feels like I am detained. I have to worry about it all the time. When they take it off, I will still feel like I have it on.” 22-year-old asylum seeker from El Salvador. Detained for 6 months. Photo: April 2018

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “At Butler Co. Jail you don’t see a person face to face. You see them on a little black and white monitor. For a 9-year-old boy to see his father that way…you know when you are there with your five children and your partner hanging around the screen and passing the phone back and forth, it’s pretty heartbreaking.” Nancy, visitation volunteer. Butler County Jail, Hamilton, Ohio Photo: September 2018

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, In the desert outside the Adelanto ICE Processing Center on Good Friday in 2018, parishioners follow representatives of the Catholic Diocese of San Bernardino in protest of immigration detention practices and in solidarity with those men and women detained inside. The group re-enact the ‘Stations of the Cross’.

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, Adelanto Detention Center, California: “When you hear the doors, you feel like you have lost yourself. You have no voice. You are invisible. The essence of being human…it feels like you have lost this.” Rodolfo (55) Lived in the US for 30 years. Detained for one year, then deported to Mexico.

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center, Louisiana: “I’m in this meeting with the ICE Assistant Field Officer and the warden of Pine Prairie and they said, ‘You know we have a contract with GEO and we try to be really good partners and we try to make sure that they always have enough inventory right here’. Inventory meaning, people.” Jeremy, Immigration Attorney

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, who I am. All my life I’ve ran from them. In detention another guy from Ghana said, I feel like committing suicide. I said, You should not give up, if you have any hope in you. But in detention you are kidnapped. You have no one to turn to. It makes you feel very pathetic. In detention what can you think of? You think of everything and you worry. And in the end you remember another you.” 28-yr-old gay man from Ghana Detained for 5 months

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “They took him to Chase County Jail…When he was detained, I thought I would be able to hug him physically, but no. It was through the window. The conditions looked really bad. My dad…he was trying to smile. It was like he was saying, Don’t come. Don’t come. But I was wanting to see my dad and see how he was doing.” 18-yr-old daughter and US citizen. Her father was detained in Chase County Jail, Cottonwood Falls, KS.

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, Elizabeth Detention Center, New Jersey: “I’ve never committed a crime so it overwhelmed me. I thought anything would happen…I never felt like a human being. Not ever one day. You are reduced to nothing. The bad part of it is that it is life lasting. Until now…I’ve never healed from that experience. I’ve never healed from life in detention. I don’t know when I will.” Asylum seeking woman from central Africa Detained for several months

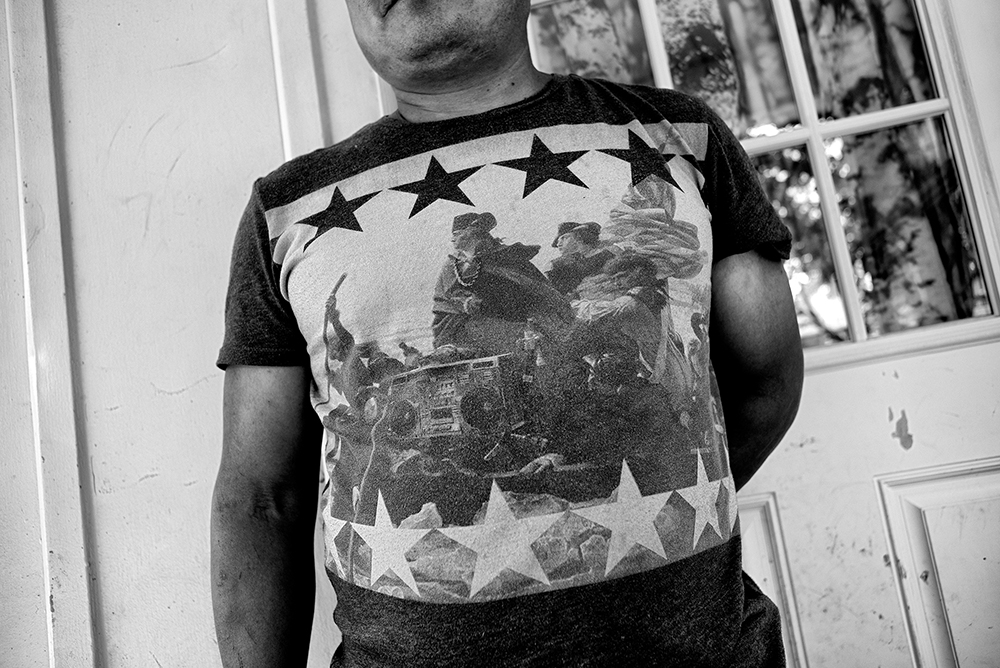

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “Immigration came for the wrong people in this community in Salem. We spend a lot and do a lot for this town. Now, people are afraid to go out. I was released and now wait for my asylum case. But, like a lot of Guatemalans who have lived here in Salem for a long time, we’re leaving soon and moving away from here. We can’t live here anymore.” 48-yr-old man from Guatemala arrested during workplace ICE raid in Ohio. Photo: September 2018

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “When we got to the jail she sounded like she was giving up. She said, Start packing up your stuff for Florida and just leave me. Just let me get deported. We told her that we can’t. We’re going to fight for her. Do whatever it takes. We’re going to help fight through.” 18-yr-old daughter and US citizen. Her mother (undocumented) was arrested by ICE after a minor traffic violation and detained in Seneca Co. Jail in Tiffin, OH. Just days after her detention and now alone, the siblings congregate in their home and discuss what to do. All four children are US citizens. Donations of groceries and other items from local organizations are piled up in the corner. Photo: September 2018

©Greg Constantine, from 7 Doors, “He was so happy just being able to see her through the glass. We only had 15 minutes. I dressed her in a bright pink one zee. She was really beautiful and she looked at him. After the visit, he called and said he would call later that night. He didn’t call. He was moved to Arizona. Then he was deported. I didn’t hear from him for five days. When he called, he was back in Guatemala.” 33-yr-old woman asylum seeker from Guatemala describes the visit with her husband while he was detained in the Denver Contract Facility in Aurora, Colorado. Photo: February 2019

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025