Sean McFarland: The States Project: California

Sean McFarland is not a photographer’s photographer in pursuit of the ideal landscape or perfect portrait. His relationship with a particular subject in the traditional sense is tentative at best. But it is here, treading uncertain ground between perceived truths and formal semantics that Sean dissects the actual act of seeing, and photography’s role in that process, into separate physical, cultural, and psychological phenomenon. Sean crosses design barriers commonly associated with different mediums, to create images that acutely communicate these different sensory sensations. If the Bay Area’s photographic history can be divided into three distinct generations or schools thus far, he represents a fourth and rising generation of photographic artists. In his own words Sean is, “actively engaged with making and thinking about photography, history, and the idyllic landscape of pictures.”

Sean McFarland’s (B. 1976, California) work explores history and the representation of landscape. He earned his MFA from the California College of the Arts in 2004. He has exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Berkeley Art Museum, George Eastman Museum, White Columns, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and Aperture Foundation. He has received the 2005 Phelan Art Award in Photography, 2009 Baum Award for an Emerging American Photographer, 2009 John Guttmann Photography Fellowship, and a 2011 Eureka Fellowship. His work is the collections of SFMOMA, Milwaukee Art Museum, Oakland Museum, Berkeley Art Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art Library. He teaches art at San Francisco State University and is represented by Casemore Kirkeby Gallery, San Francisco.

Men come and go, cities rise and fall, whole civilizations appear and disappear—the earth remains, slightly modified. The earth remains, and the heartbreaking beauty where there are no hearts to break…I sometimes choose to think, no doubt perversely, that man is a dream, thought an illusion, and only rock is real. Rock and sun. – Edward Abbey

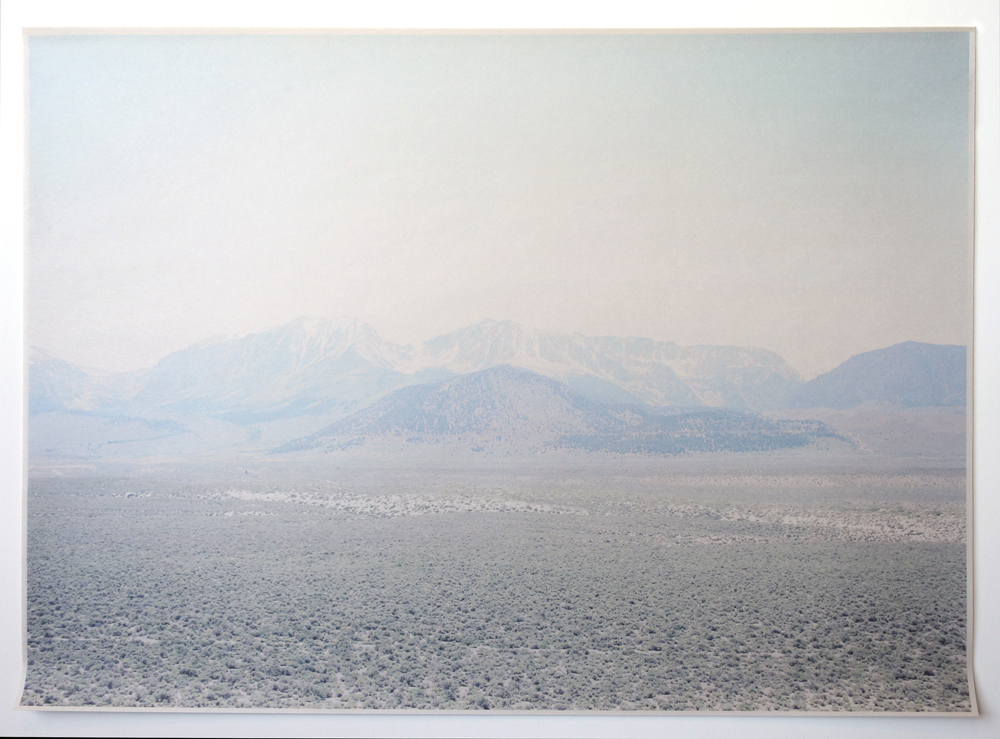

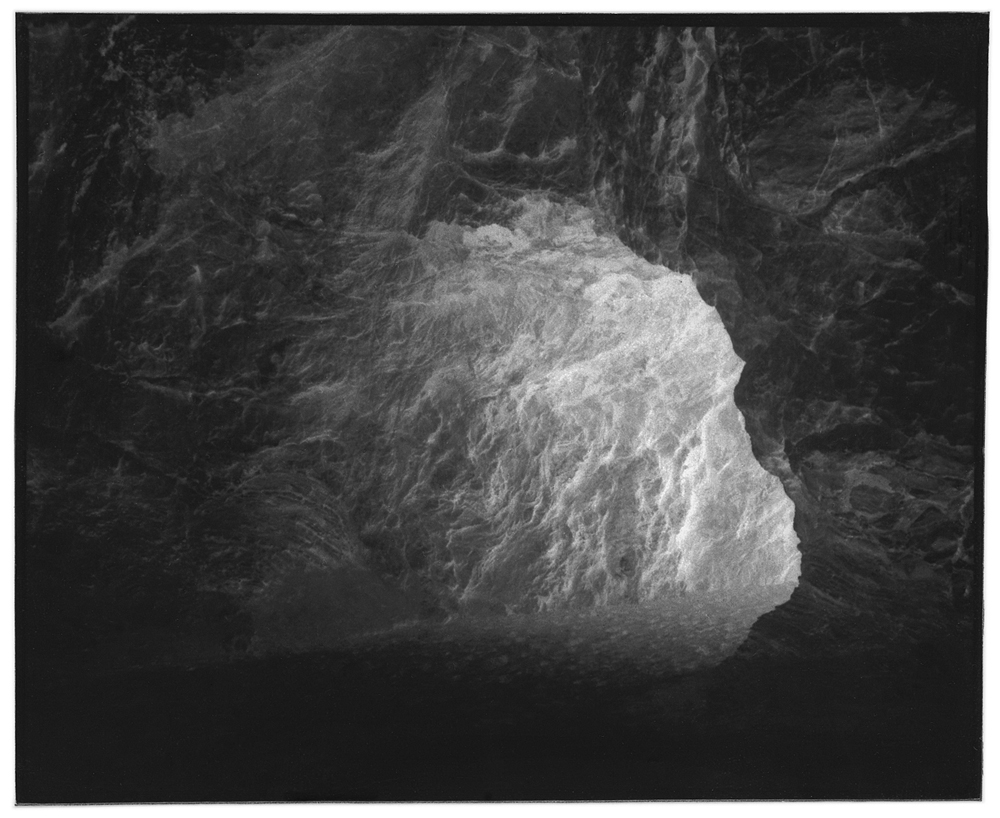

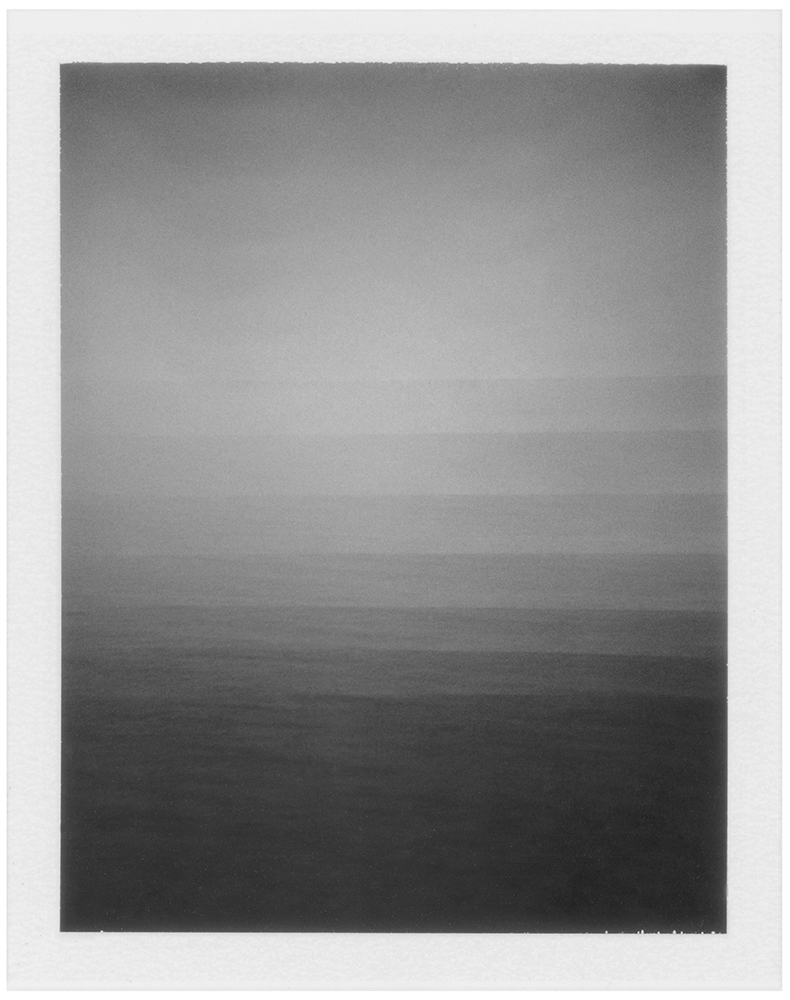

There are several modes of viewing the landscape -‐ in person directly, indirectly through books and magazines, maps and scientific documentation, and through the work of others; to me, no one form of sight is more pure than another. In my work I am less Interested in reproducing the pictures as seen by the early photographers of the American Landscape than in the landscapes created through their images. The subsequent alterations of photographic representation, cultural shifts, and environmental impacts that have resulted from their pictures have forever affected our relationship to the earth and our relationship to image. Like the early landscape photographers, 19th century image-makers produced documents to show us the moon, Saturn, bones inside of our skin, and the forces of nature imperceptible to the human eye. They employed telescopes, new photographic technologies, and often artifice itself to represent the unknown world through pictures. These images, along with early western landscape photographs were evidence of the once unknown, attempting to prove the existence of far off places and enigmatic phenomena.

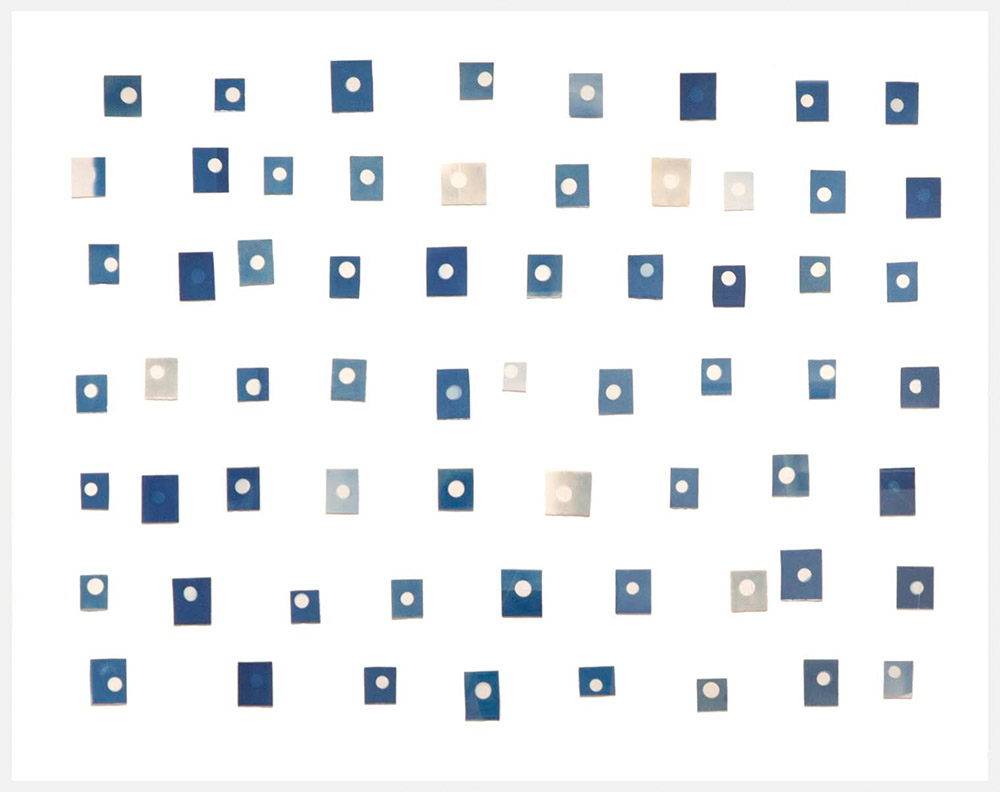

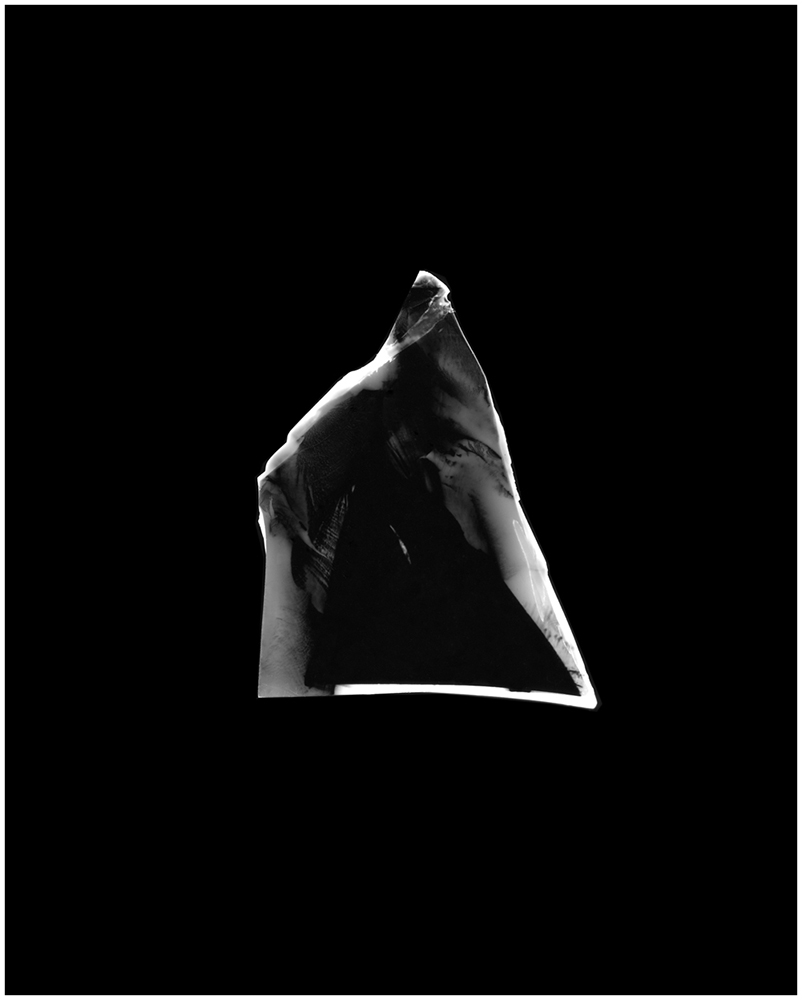

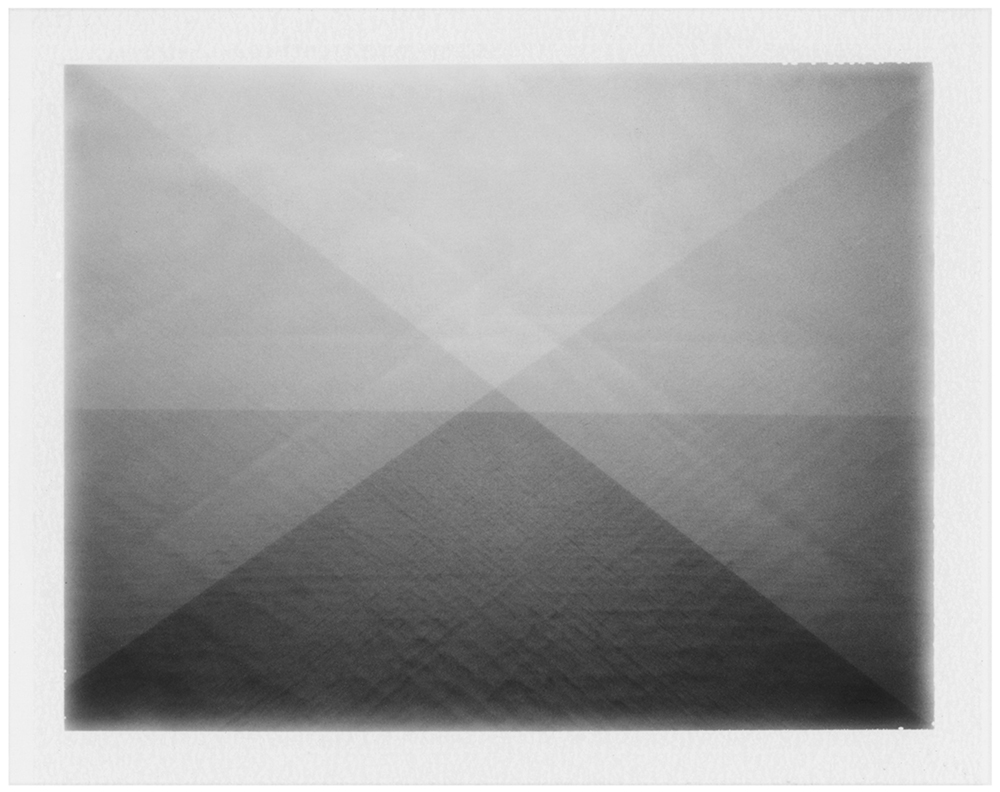

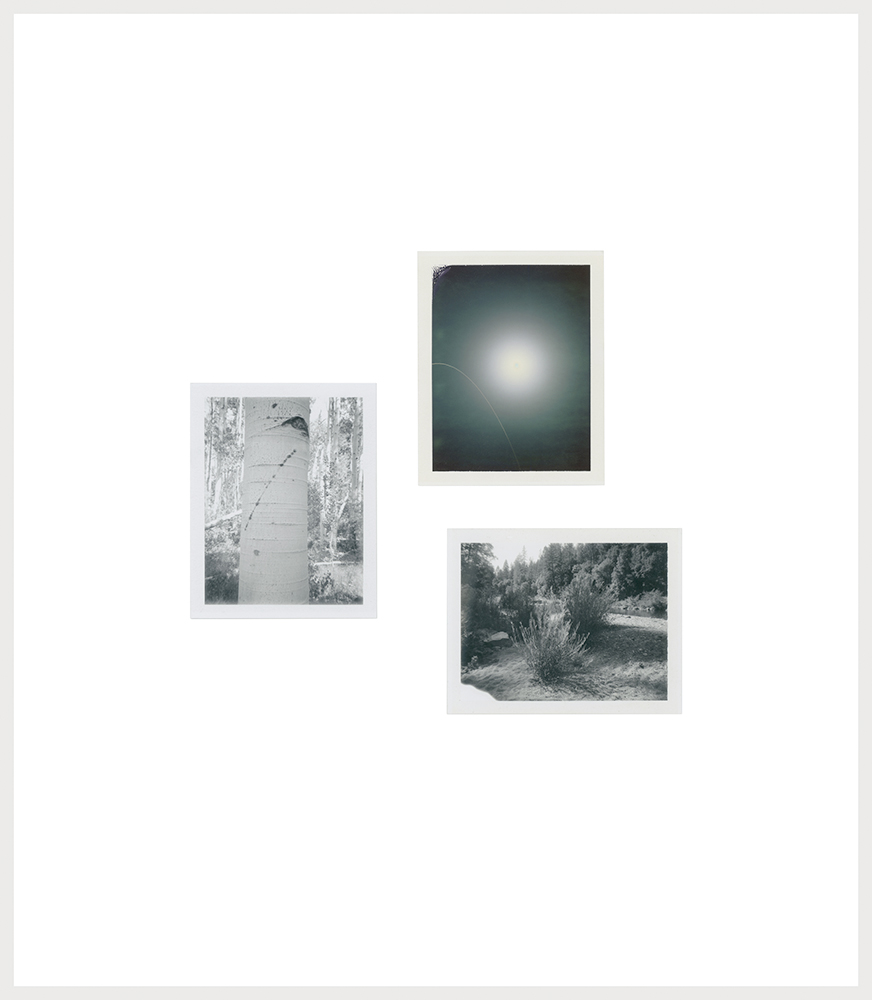

My work is part theater, part documentary, examines photographic veracity, the materiality of photographs, and how our perception of the earth is ever changing. I am currently building upon a body of work that consists of collections of records: photographs, videos, books and drawings presenting nature as literal artifice. The distances between these records and seeing, hearing, and feeling the landscape are irreconcilable. The record is a go‐between for experience, a stand-in for a stand-in. Produced from the abstraction of man-made materials and elements from the natural world, my work consists of appropriated/mimicked natural forms, pre‐existing photographic images, as well as original photographs. These works continue to blur the lines between unbiased documentation, expectation, and sentimental mythology. Broken glass can become a mountain, a small circle becomes the moon, color pictures are made from black and white. They are representations of us, and the mythological construction of wilderness and the west.

Sean, you are a Californian for generations. How does being a native to this state and geography influence your creative and conceptual relationship with the landscape?

California has golf courses in the desert, Disneyland, the Pacific Ocean, the Eastern Sierra, suburbs, cities, farms… It’s complicated, diverse, and full of contradictions. The authentic and the artificial are always battling for attention, and more times than not are both beautiful and ugly and difficult to tell apart.

In 2014 I moved to upstate New York for a year – the opposite of coastal and high desert landscapes that are the usual subject of my work. I always make pictures of where I am, and when I can’t, I make pictures of where I want to be. Working in upstate New York consisted mostly of generating content from the photographs I brought with me instead of making new exposures. I wanted to go back to California every day, if I couldn’t go physically, I’d go (as best I could) through pictures.

It taught me a lot about how photographs work, at least for me – about place, time, and the irreconcilable distance between experience (being there and seeing), and a record of that experience (the photograph).

I moved back to California in August 2015.

Before we get too deep into why you do what you do, perhaps you could help us understand some of your very specific and sophisticated working methods. For example, what exactly is a dye diffusion print, a dye diffusion transfer print, and a cyanotype? What is your urge to print on newsprint in some cases, and how do you even make an 8×12 foot pigment print on a single sheet of paper?

Dye diffusion print/dye diffusion transfer is the technical name for an instant photograph, like a Polaroid. More than most pictures, they’re slippery; implying that what they show was witnessed by a camera, then held in the hand of the photographer afterward. They are assumed to be accurate and truthful because of their program and how they exist as documents. Their subjects are often vacation snaps, family or party pictures, the ordinary. We have become very good at decoding them, so much so that when sublime or spectacle becomes their subject, even if presented as artiface, they can be seen as authentic.

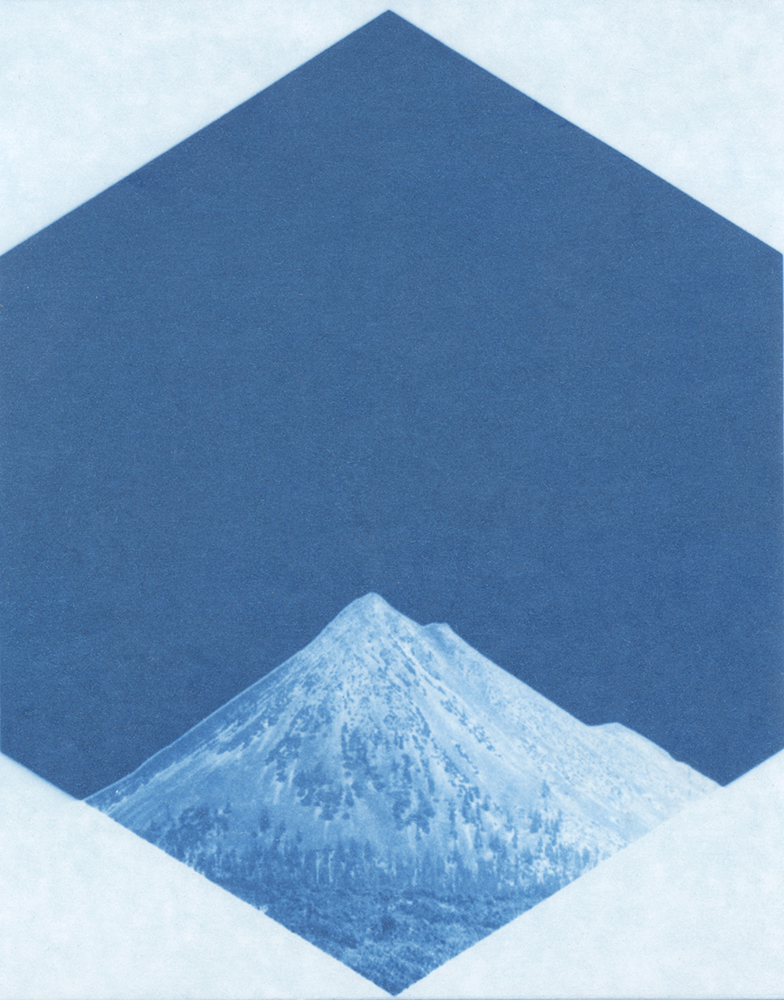

Cyanotypes are cyan-blue photographic prints that get their color from potassium ferricyanide and ammonium iron(III) citrate. They’re exposed with UV light and processed using water. They can be made almost anywhere. I like that they can be exposed by the sun and allude to the color of the sky without using a negative or a camera – just light.

Newsprint changes – photographs are supposed to stay the same, never change color or fade, showing us a frozen record. I started using newsprint in 2006 but it has only recently become a material I use often. I had been wanting to make photographs that work like clocks, reminding us of the passage of time. When you’re looking at a landscape in real life, most of the changes or passage of time (aside from the daily cycle of sunlight or clouds) are imperceptible. Mountains aren’t permanent but appear to be – it’s easy to forget that we are connected to them, and that they, like us, are vulnerable and cannot exist forever. A picture of a mountain on a piece of newsprint changes. The paper visibly fades at a rate we can perceive allowing us to see the mountains age much like we watch hands of a clock remind us of time relative to our own existence.

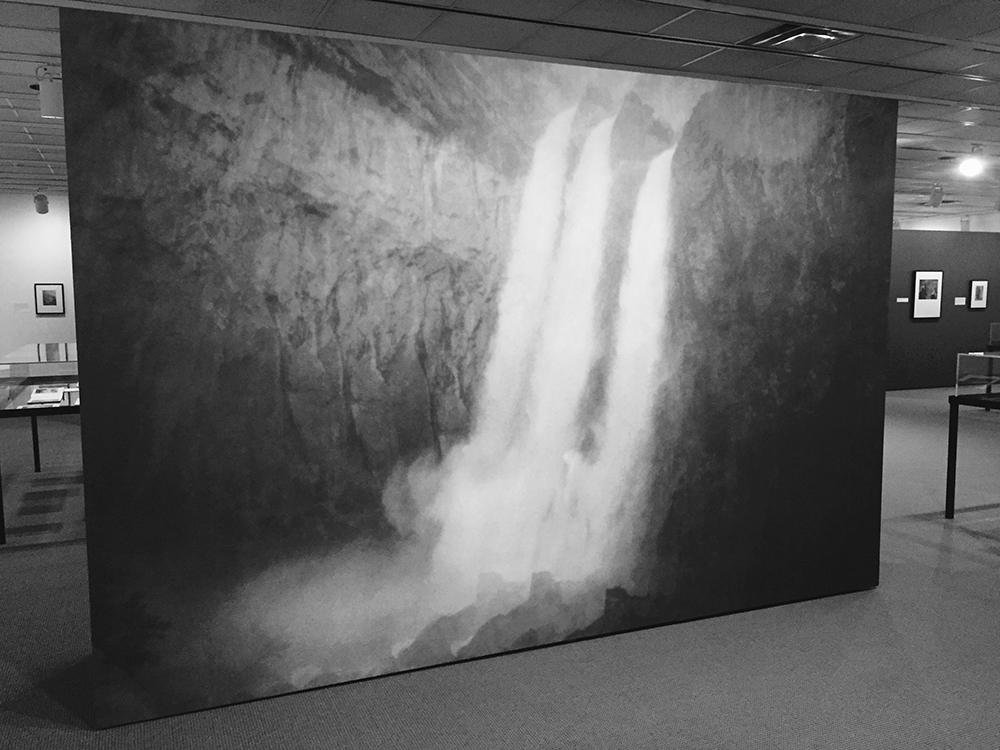

The 8×12 foot piece is made by printing on multiple 44” wide sheets of adhesive vinyl. The image is a scan of Polaroid of Yosemite Falls where it has been exposed three times on the same sheet – I wanted to turn up the falls, try and make them look as powerful as it feels to stand in front of them.

You describe being less “interested in reproducing the pictures as seen by the early photographers of the American Landscape than in the landscapes created through their images. The subsequent alterations of photographic representation, cultural shifts, and environmental impacts that have resulted from their pictures have forever affected our relationship to the earth and our relationship to image.” What are some examples of the cultural shifts and alterations of photographic representation that you feel are a direct result of this early American Landscape imagery?

Early landscape photography shaped and forever changed the West and our relationship to it. It helped fuel manifest destiny, but also helped create the National Parks.

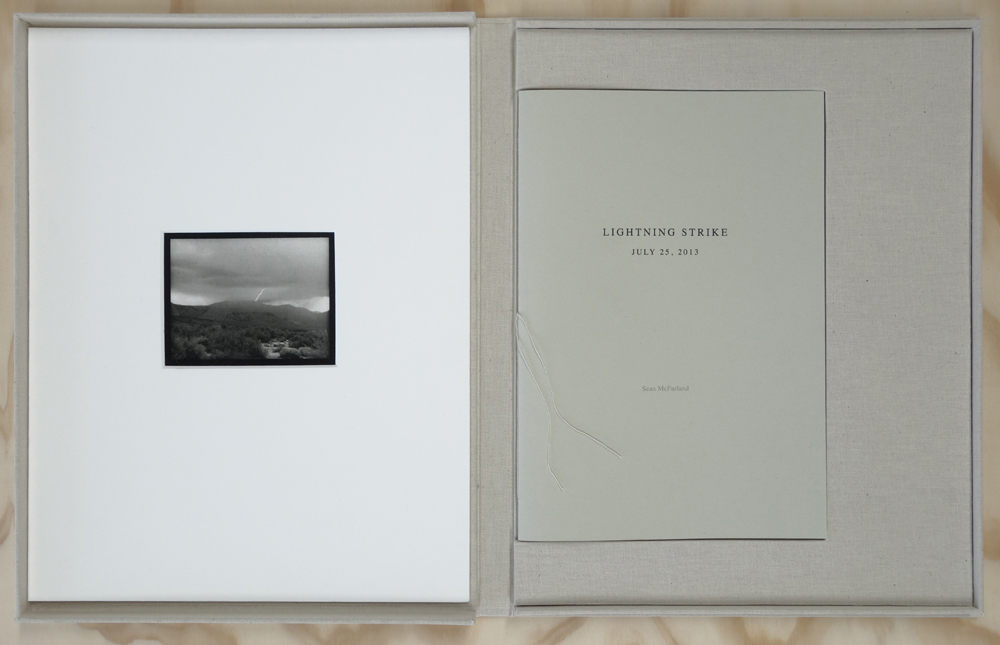

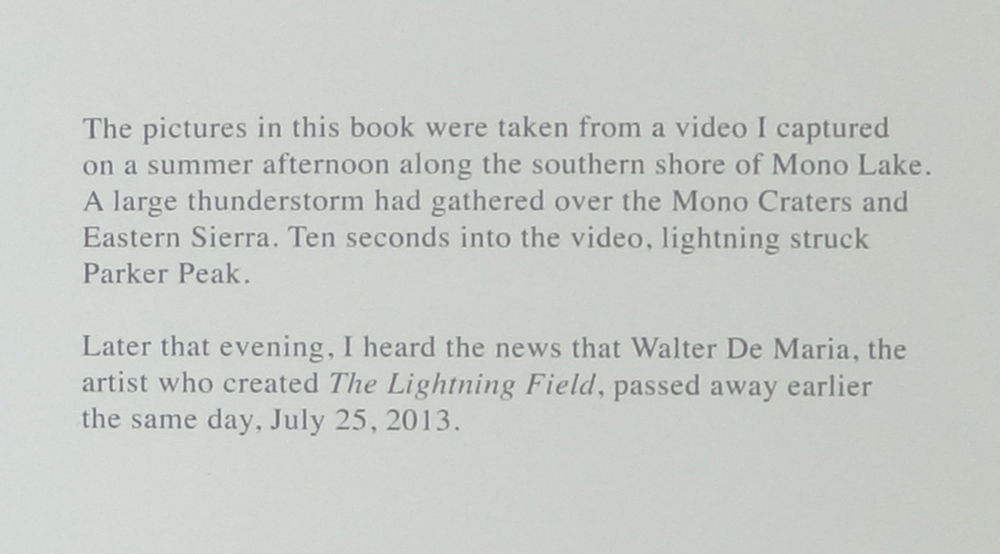

Can you tell us a little bit about the Lightning Strike project you shared recently at the San Francisco Book Fair?

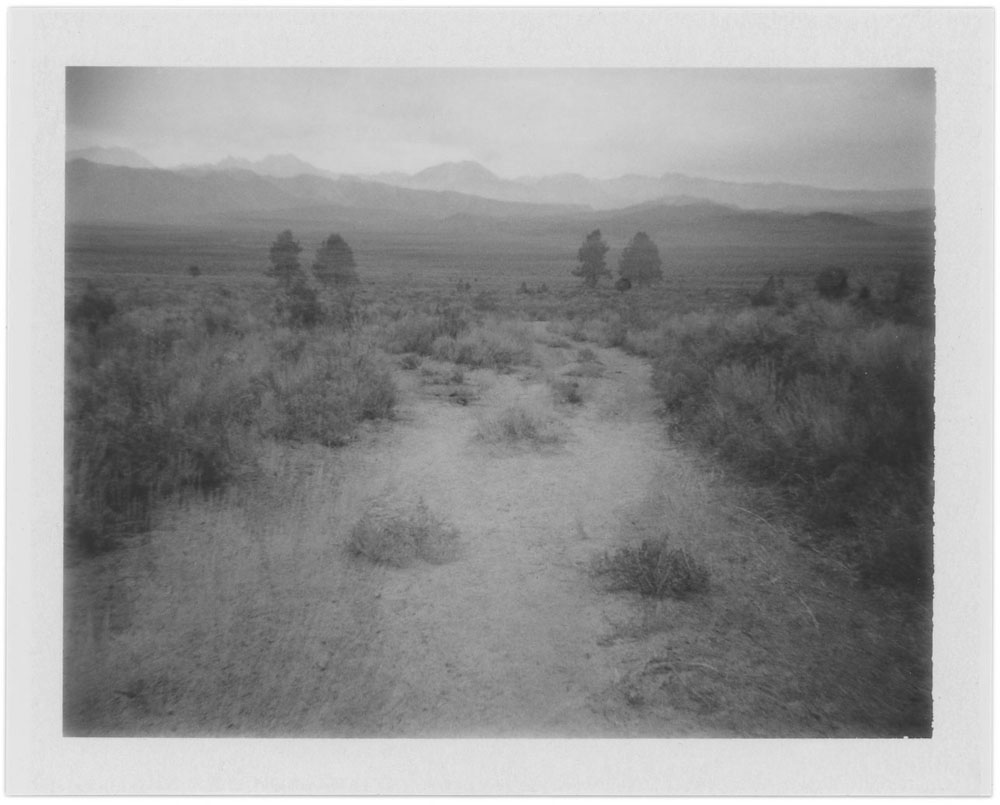

A few years ago I was working on a trail crew doing travel management work in the Eastern Sierra. We were looking for illegal off highway vehicle (ohv) roads called trespasses and closing them by camouflaging their existence as opposed to placing a barrier at their entrance.

Heading back to camp one day there were giant thunderheads gathering over the mountains so I started shooting video with my phone, hoping to capture a strike of lightning. I did. When I arrived back at our camp, I was looking at the news and saw that Walter de Maria, the artist who created the Lightning Field (Please link- http://diaart.org/visit/visit/walter-de-maria-the-lightning-field) died earlier that day, July 25, 2013. I had the video and made several failed attempts to make work about it for two years. It finally took the form of a book or as much a of poem as I could make it. It’s a small edition of 100 and shows the frames containing the lightning and a short afterward.

I’m working on a new book project now about a ranger named Rockwell, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and some of my pictures. It also deals with a coincidence or echo (which is probably a better way to think about it).

Finally, to celebrate the National Park’s 100th anniversary the George Eastman Museum mounted an exhibit titled Photography and America’s National Parks. Can you tell us a little bit about your participation in this show and what voice you feel that your work added?

The exhibition is curated by Jamie Allen from the George Eastman Museum who also wrote a wonderful book for the show, published by Aperture.

Photographs in the show range from the 19th century to the present. It’s probably best to read more about it here!

I’m incredibly honored to be in the exhibition as much of my work is a direct response to and heavily inspired by the other artists in the show. I’m not exactly sure what voice I’m adding other than being a contemporary artist, making and thinking about photography, history and the idyllic landscape of pictures. If you’re in Rochester, go check it out!

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Meghann Riepenhoff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 14th, 2016

-

Kevin Kunishi: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 13th, 2016

-

Adam Katseff: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 12th, 2016

-

Nigel Poor: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 11th, 2016

-

Carlos Chavarria: The States Project: CaliforniaAugust 10th, 2016