The States Project: Oklahoma: Crystal Z Campbell

Reenactment, exhibition at BRIC Arts © Crystal Z Campbell, 2018 Photo Credit: BRIC and Etienne Frossard

I can not recall how I got acquainted to Crystal Z Campbell. However, I am certain that it must be from some mutual art connections we have in Tulsa, OK. Beside seeing each other in various gallery openings, discussions, and workshop, we even bump into each other at the grocery store. Conversations about art making and our community seem to have no physical limitation to us. I am always struck by Crystal’s calmness and her knowledge of the art field. Yet, contradict to her soft-spoken manner, a strong, fierce art making attitude is what draws me into her and her work.

Crystal Z Campbell is a multidisciplinary artist and writer of African-American, Filipino, and Chinese descents. Campbell’s practice ruptures collective memory, imagines social transformations, and questions the politics of witnessing using physical archives, online sources, and historical materials. Recent works include a collaboration with a molecular geneticist investigating Henrietta Lacks’ immortal cell line, Greenwood and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and an examination of gentrification via a 35mm film relic salvaged from a now demolished black Civil Rights theater in Brooklyn.

Campbell exhibits internationally: ICA Philadelphia (US), Artericambi (IT), Artissima (IT), Studio Museum of Harlem (US), Futura Contemporary (CZ), Project Row Houses (US), BRIC (US), de Appel Arts Centre (NL), Visual Studies Workshop (US), BRIC (US), and SculptureCenter (US) amongst others. Selected honors include the prestigious Pollock-Krasner Award, MacDowell Colony, Skowhegan, Rijksakademie van beeldende Kunsten, M-AAA Grant, Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program, Sommerakademie Paul Klee, Smithsonian Fellowship, Flaherty Film Seminar, and Yaddo. Campbell is a former social worker, and is currently a Drawing Center Open Sessions Fellow and third-year Tulsa Artist Fellowship recipient. Campbell lives and works in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Reenactment, exhibition at BRIC Arts © Crystal Z Campbell, 2018 Photo Credit: BRIC and Etienne Frossard

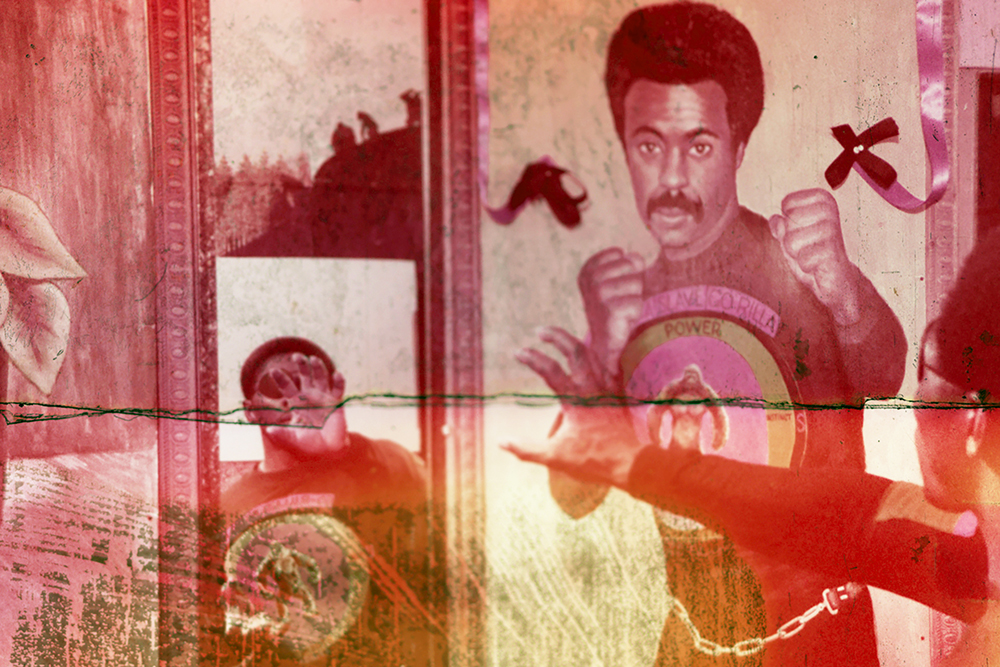

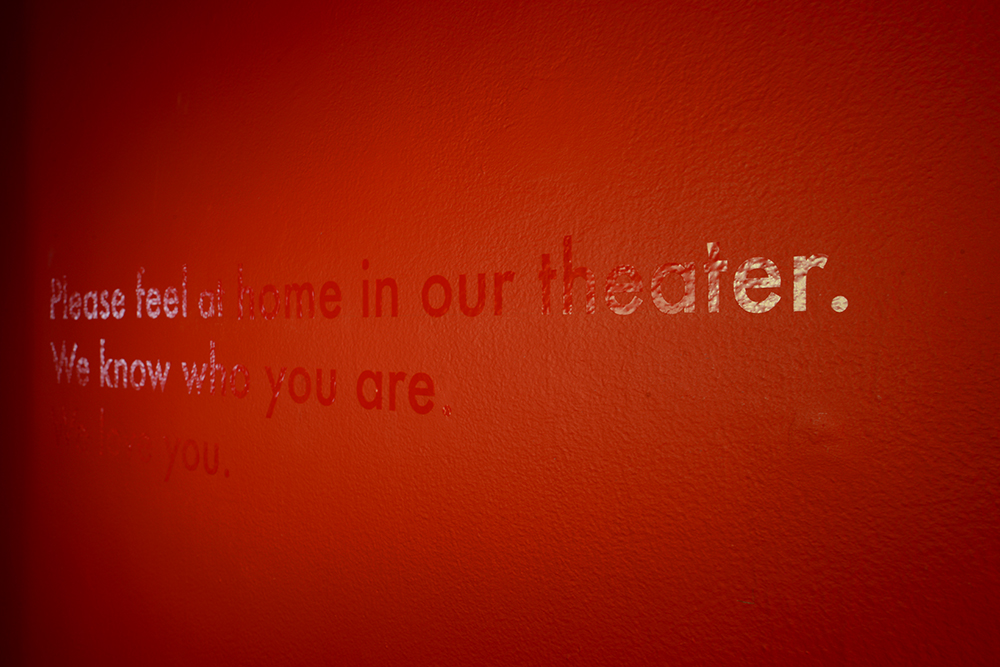

Have you been inside The Slave Theater, my friend asked. I glanced across the street at the Brooklyn building, a hand painted black and white sign exclaiming Slave #1 butting a rough map of Africa beckoned. My head roved around the building’s interior: peeling painted murals of black leaders, Bruce Lee and community empowerment anecdotes lined the walls. I nearly tripped inside the theater proper. Before thinking, the culprit was in my hands. A man squatting the building made his way over. I asked if I could have this artifact of the theater. He gestured.

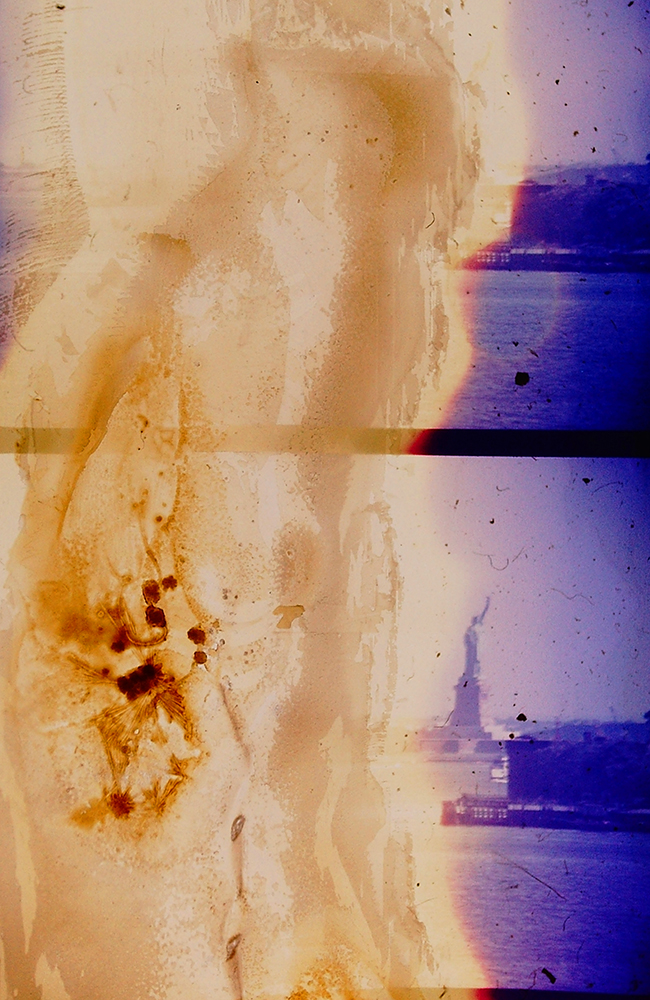

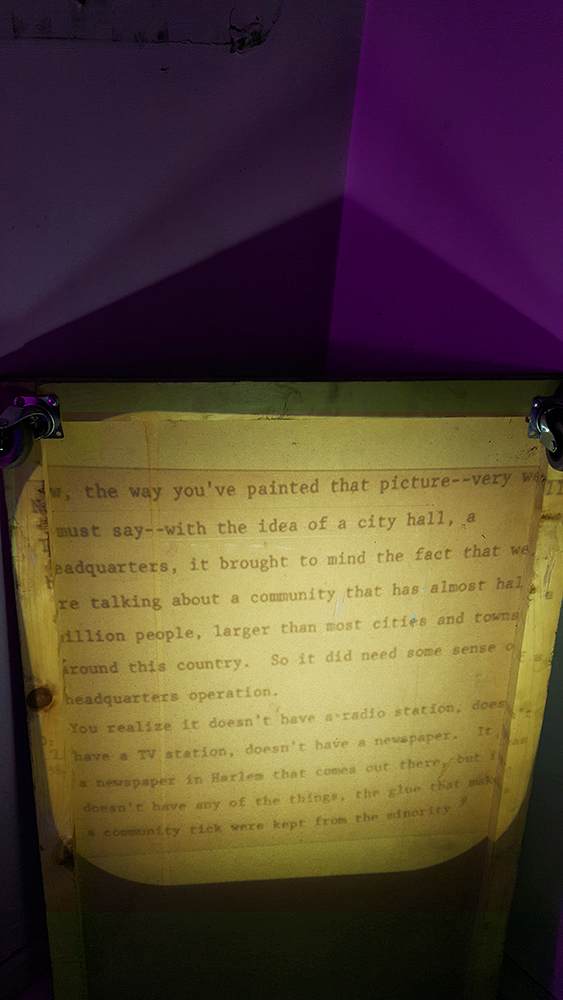

I carried this 35mm film around for six years like a relic. I sent it to film labs in Europe and the US, where it was repeatedly rejected for digital transfers. The film lacks titles or credits, and was repeatedly diagnosed with vinegar syndrome: buckled, peeling, odorous, brittle, severely discolored. At Yaddo, I cobbled a makeshift film spool from plumbing pipes and flanges and over the next few months, manually scanned over 20,000 images from this film. Meanwhile, The Slave Theater, a critical site for Black Civil Rights of the 1980’s in Bed-Stuy, was razed last year for the construction of condos.

Eight years ago, I could not have known I would be grasping a relic of black history, which in turn, would become a relic of Bed-Stuy’s gentrification. I journeyed back to New York two years ago to find information in the archives, and only one mention of the Slave Theater was noted. How can a place disappear? And if a place can disappear, then what with its people? As an artist currently living a few blocks from the site of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, I observe tactics of cultural erasure, land grabs, accountability silenced by amnesia and an unreconciled past that paralyzes the full potential for restorative justice. Witnessing is a political act of looking, remembrance, and acknowledgment. I create work about events, people, and places to invite historical reconsiderations, prompt questions about the politics of witnessing, and warrant value through slow, close, and careful observation.

Reenactment, exhibition at BRIC Arts © Crystal Z Campbell, 2018 Photo Credit: BRIC and Etienne Frossard

Anh-Thuy Nguyen: Would you mind leading the readers to your discovery and process of salvaging this work?

Crystal Z Campbell: I was living in New York City at the time and prepping to leave, after being priced out of my apartment. A friend suggested we take a walk, and we met halfway between our neighborhoods. She asked if I’d seen the Slave Theater, and I laughed. Slave Theater? What I didn’t know at the time was that the Slave Theater was a critical site for the Black Civil Rights Movement in Brooklyn in the 80’s and had a rich history of protests (including at least one for Tawana Brawley), art, guest speakers, and films that charged people in the community. Despite the theater being squatted, we snuck inside to have quick glimpse at the hand-painted murals. On the way out, my footsteps were thwarted by a hard object. I picked it up instinctively. It was a 35mm movie reel of film.

ATN: I remember you shared that having the film reels scanned was a “process,” I am curious what was going on in your mind?

CC: Seven years after finding the film, I was scheduled for a residency at Yaddo. I didn’t have a clear project in mind, so I decided to revisit this film. When I arrived, I mentioned to my studio neighbor that I had a 35mm reel of movie film and needed to create a set-up to scan it. We trekked to DIY shops in the area and cobbled together white plastic plumbing flanges to mimic a reel. Eventually, I would scan 20,000 frames from the film salvaged from the Slave Theater.

Initially my questions were journalistic, but I watched the film sideways through a cheap microscope for over four months on a low-resolution screen. The film would often crumble into pieces as I held it in my hands. Over time, working with the film was an exchange of images for marks, stains, fingerprints, dust, hair, oils, and sweat. Through this hyper-slow cinema experience of critical viewing, it dawned on me that the film itself is a witness. It witnesses through the camera, but also bears the mark of its own organic life and the forces that have acted upon it. It is a witness of how Bed-Stuy’s black community was neglected for many years by the city of New York.

ATN: After you managed to save the reel, what influences your installation’s decision?

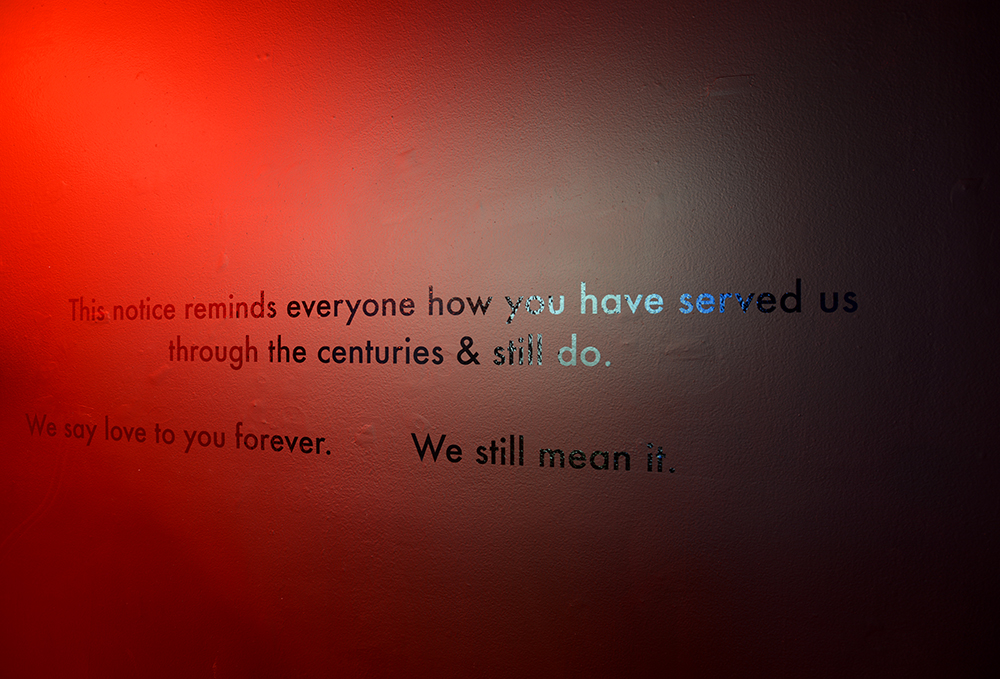

CC: The Slave Theater was destroyed when I exhibited the work for the first time for further commercial and residential development of Bed-Stuy. It was hard to observe the destruction of an architectural site that seemed integral to Black Civil Rights, culture, local history, and adorned with art and consciousness disappear for the prospect of something devoid of cultural specificity, of history, of those values. The film is but one of many relics of gentrification, and I’m constantly engaged with these questions of where cultural and historic value lie. Value is often transmitted through narratives and stories that are repeated.

I’m sensitive to the narratives of a site. I’m constantly considering the land a work potentially stands on and how the viewer can engage with the work. The first installation of Go-Rilla Means War was a diptych of 35mm synced slide projections at SculptureCenter. That version had archival images and film stills and required the gesture of looking akin to stopping at a crosswalk, something residents in Bed-Stuy repeatedly had to petition the city for. In Nashville, the film is screening at the former Woolworth’s lunch counter come restaurant that was critical to the sit-ins, opening up questions about the commoditization of these political histories and the role of food in gentrification.

The dream installation is to show Go-Rilla Means War with Randolph Rogers’ sculpture of Nydia, a neoclassical sculpture referenced in the film. Nydia is a blind enslaved woman who was constructed with symbolism from Pompeii, a site both preserved and destroyed following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. On one hand, I’m intrigued by the problematics of disaster capitalism. In addition to the obvious land grabs, I want to create a contrast between an object that has been so carefully preserved, next to the erasure and deterioration of this film and community. Whose voices are heard, recorded, documented? Who preserves the culture that doesn’t live in archives? Who has the capacity to curate vs. who has the ability to care? And how do these decisions perpetuate the narratives about which parts of culture are valuable and whose culture has value?

ATN: Are you considering yourself a social practice artist?

CC: What is social practice art? I’ve never been a fan of labeling my practice, mostly because I work in many different mediums and like to retain the freedom to evolve as an artist without those constraints. As a former social worker, I question the righteousness of what social practice implies, that art is a means to reach a specific politicized end in some way. I don’t know if my work has that level of pointedness all of the time, though I do become intrigued by the possibility of intervention and audience engagement and am deeply motivated by ideas of justice.

I’m guilty of being more interested in questions than straightforward answers. I prefer to leave a work open, to give a viewer space, and if I can do that within the realm of social practice, so be it. But I’m also curious about other ways to describe this work. Sometimes there’s a loss in defining something that precedes the experience of the thing itself. But I do see my work as some sort of service, though my case loads are now historical anecdotes tied to contemporary instances of injustice.

ATN: I am curious about the meaning and/or the decision for your title “Go-Rilla Means War”. Would you mind extend on this?

CC: Go-Rilla Means War is a line taken directly from uniforms worn by a fraternal order of martial artists in the film. I was thinking about how this film will circulate, and how nebulous language can appear. “Go-Rilla” is a homophone and a clue to this film. There’s an obvious reference to guerrilla fighters and resistance and an added layer of blackness that requires unpacking. The logo for the fraternal order in the film is a go-rilla––a well-chronicled racist comparison intended to be a derogatory nod to the black body. Here it has different implications.

The maker of this film, whom I have yet to verify, was acutely aware of (mis)perceptions. I decided upon this title armed with the sensibility of these slippages, and the notion of the signifying monkey who outwits opposition as a form of resistance. I also wanted a linguistic trace of this film, which has been suppressed and decaying for decades on the theater floor, to be reanimated by rolling these words off the tongues of people who speak its name.

ATN: You travel and move quite a lot to for your practice, would you share with us how you manage to balance your creative practice with constant physical moves?

CC: I’ve been in Tulsa for almost three years come January. It wasn’t quite the return home, since I’ve never lived here. But it a return back to my home state: Oklahoma. Over ten years, I experienced the fabled odyssey of trying to find home. I wandered through towns in Iceland, San Diego, New York City, Marfa, and smaller stints elsewhere but spent the longest part of that time in Amsterdam. I feel very fortunate that my work requires frequent travel, and it has shifted my practice.

My practice relies a lot on space, though I’ve had to become more flexible. I also frequent archives, so I build the research into the travel when I can. I’m grateful to be able to work like this, and to be able to edit the same video in different countries and cities with the same piece of equipment. Consequently, I’ve also been writing more. When I get back to my studio, I take all the components and play with them in space and make messes I can leave. And though I may long for the closest geographical version of home I know, I’m still unsettled and rattled by this place I’ve landed. Both Oklahoma and Tulsa have mysteriously figured back into my projects in concrete ways.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026