Al Brydon: Solargraphs

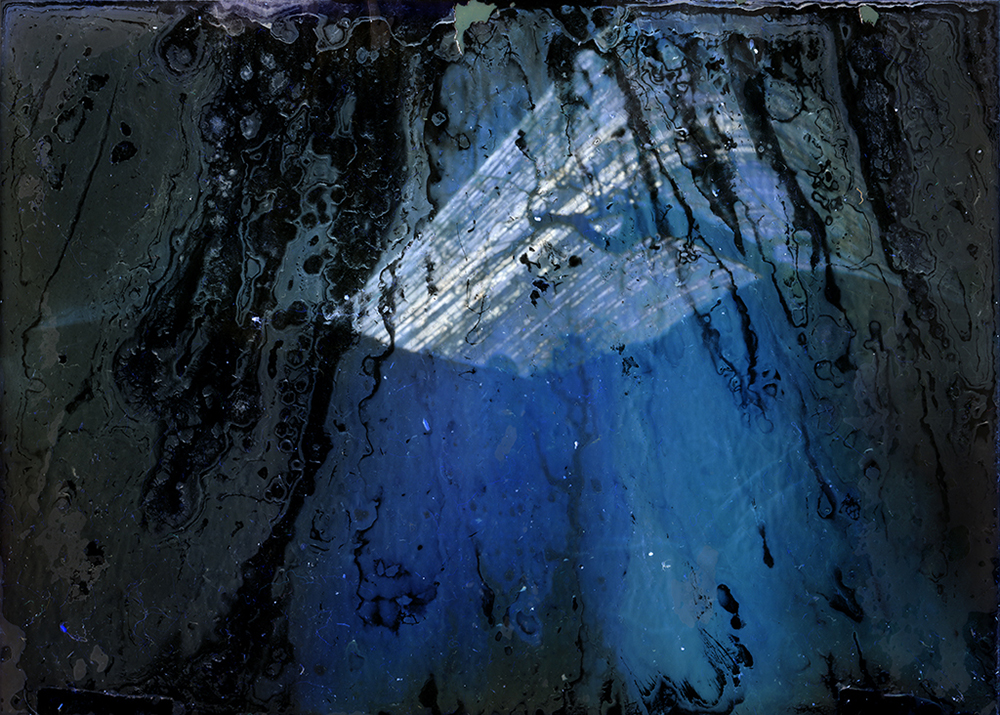

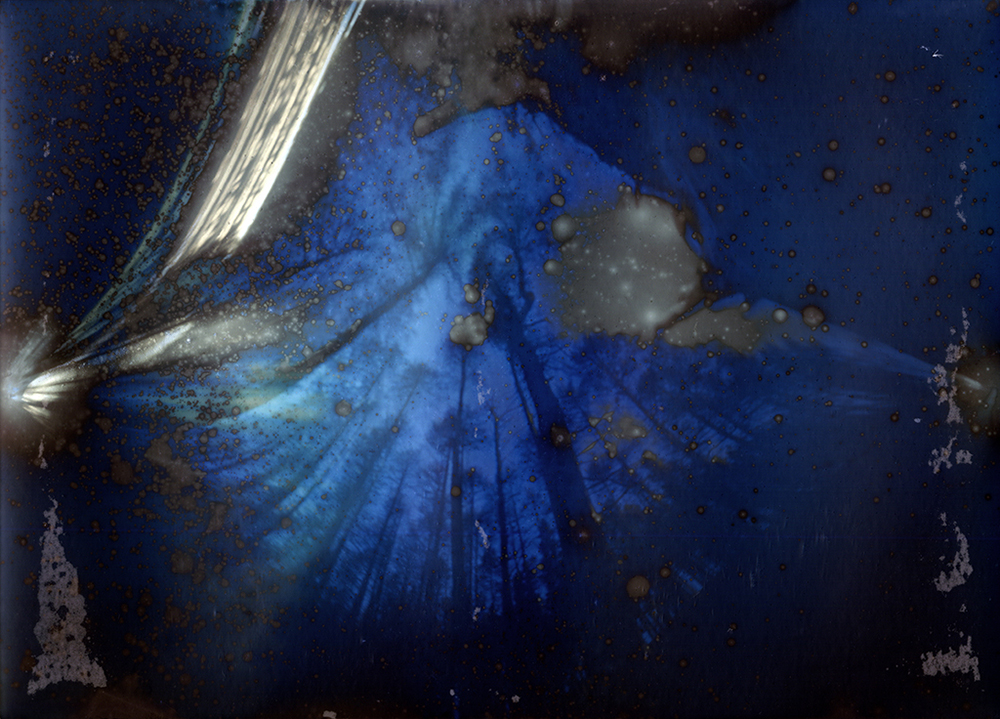

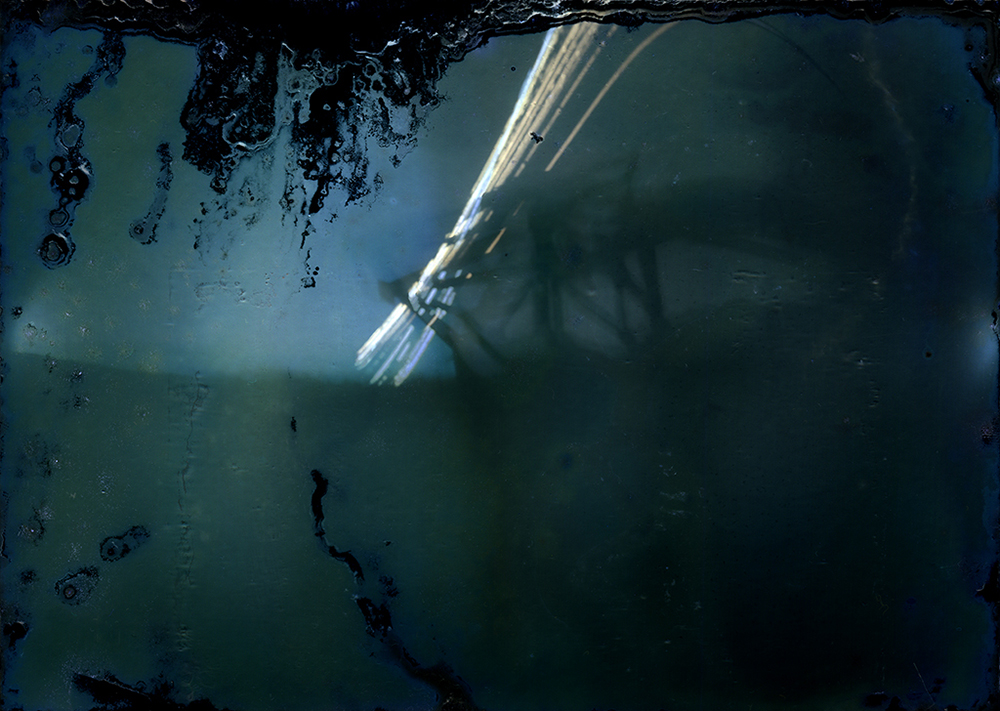

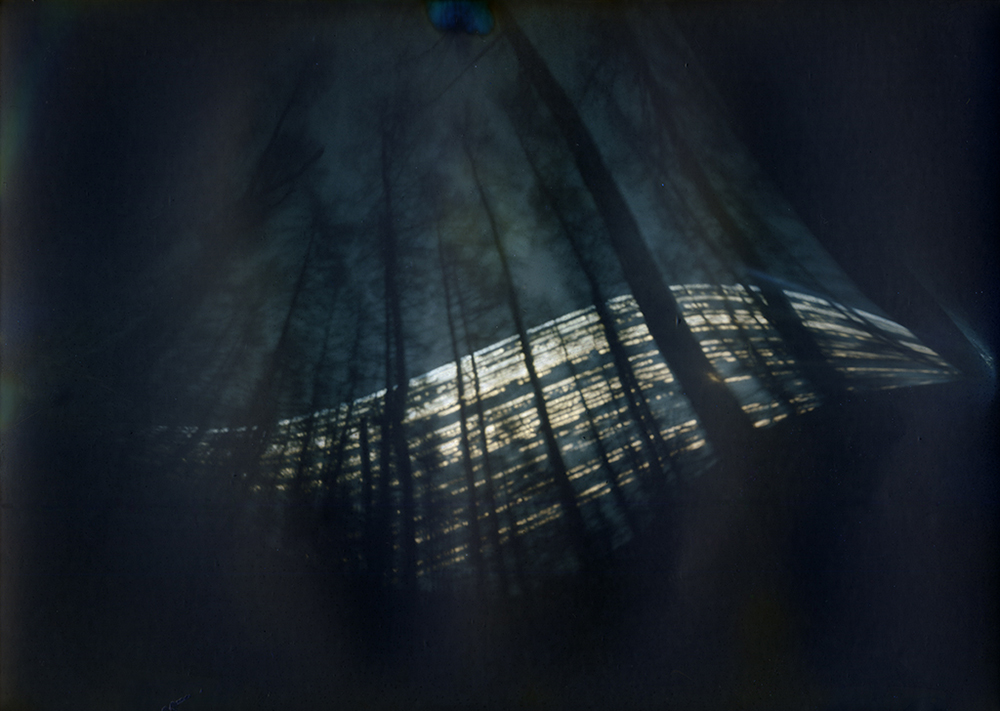

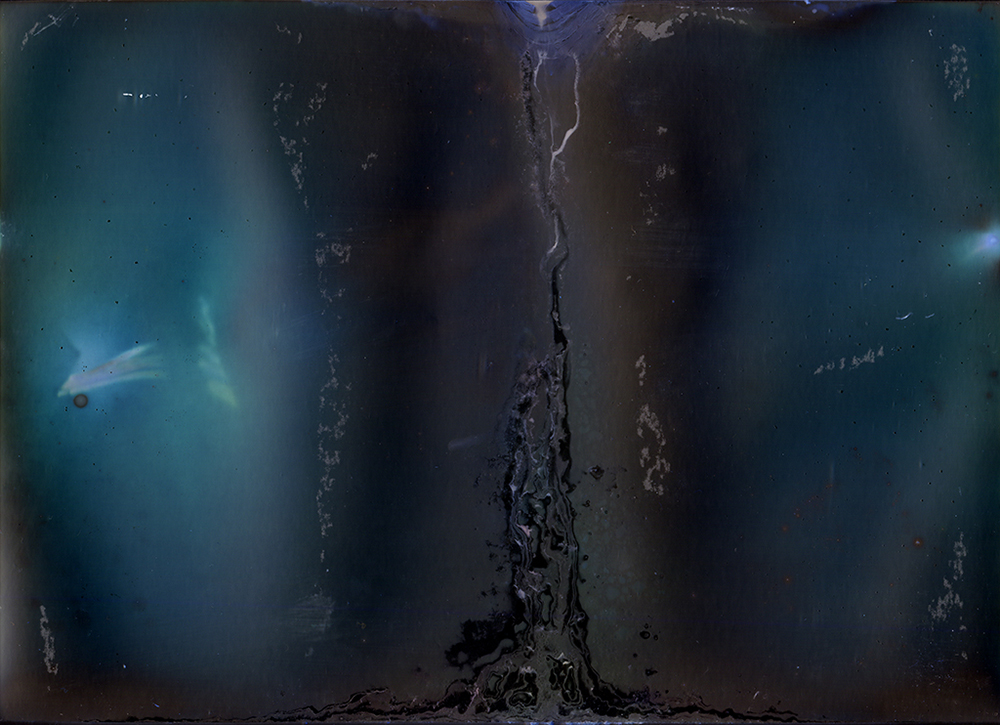

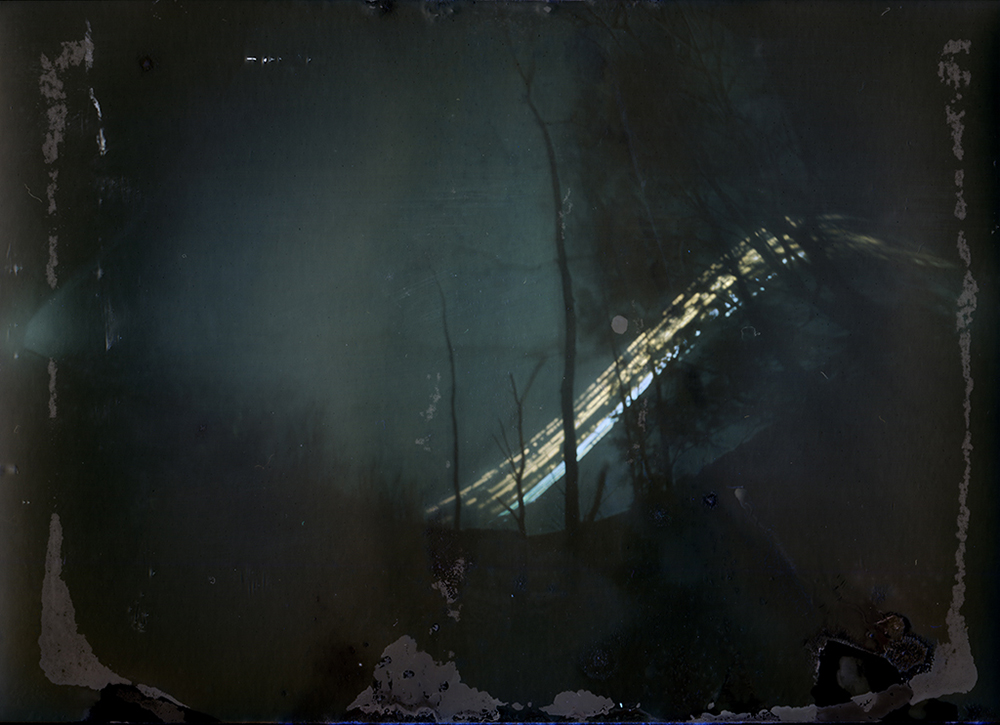

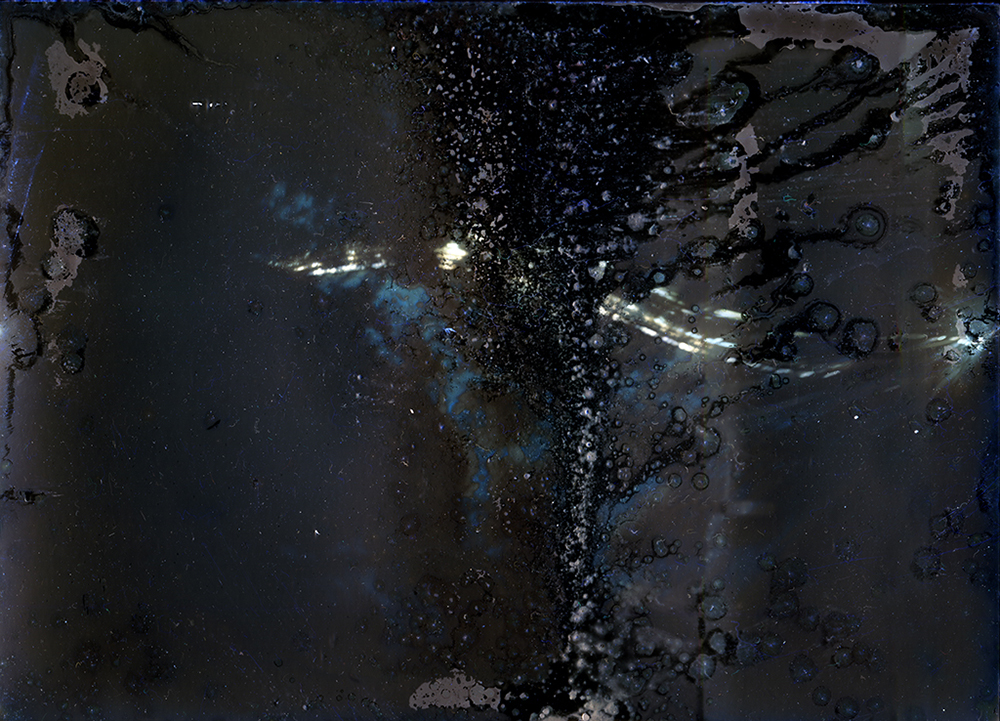

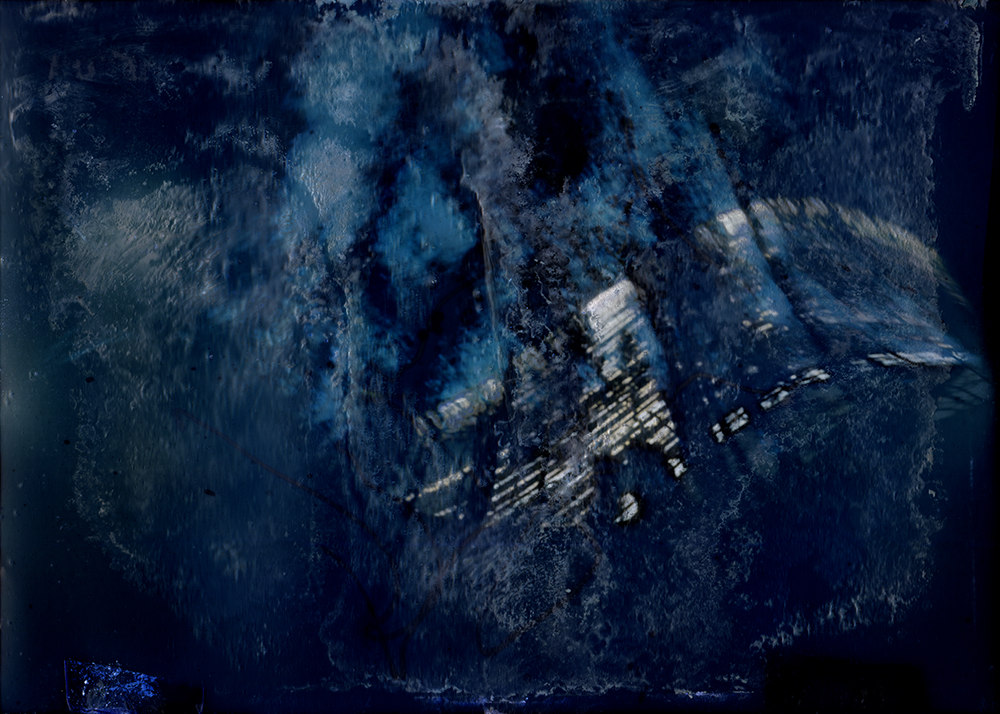

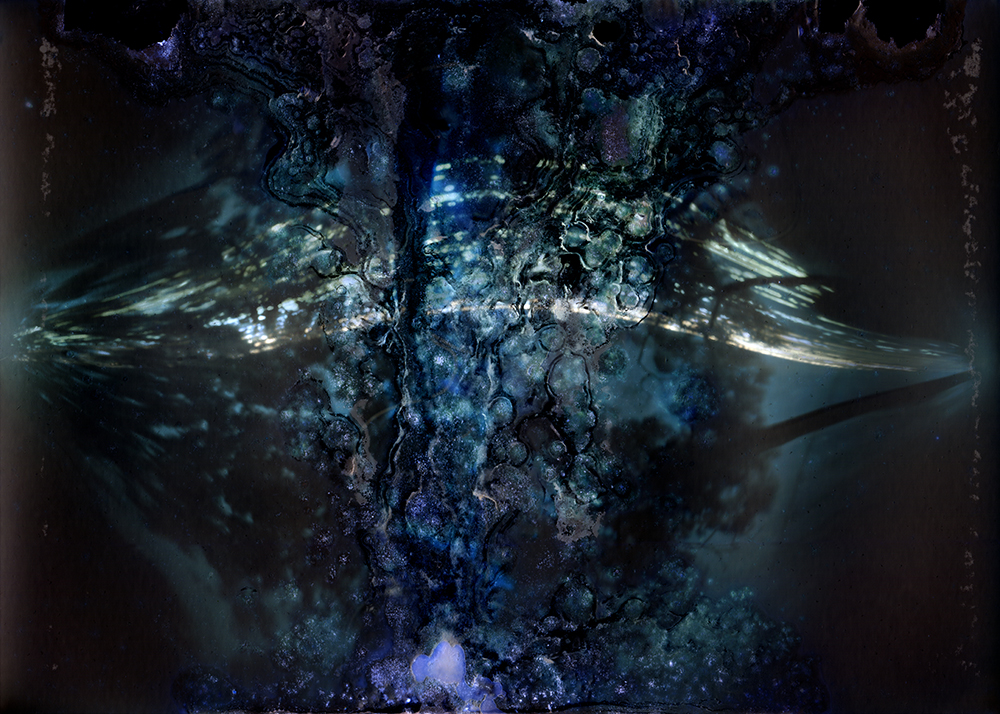

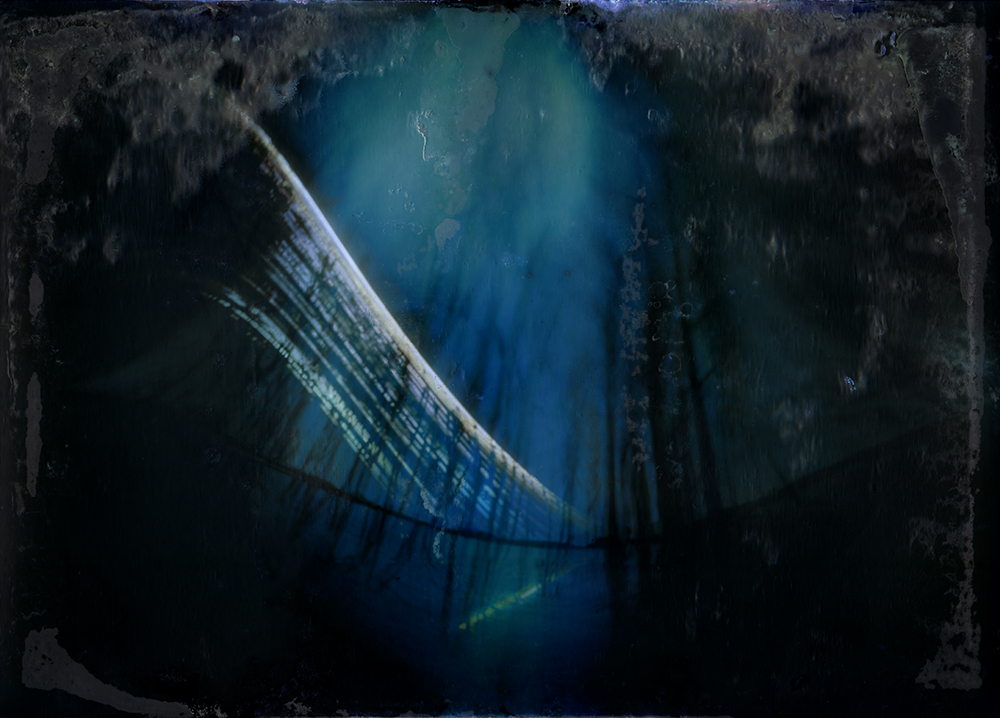

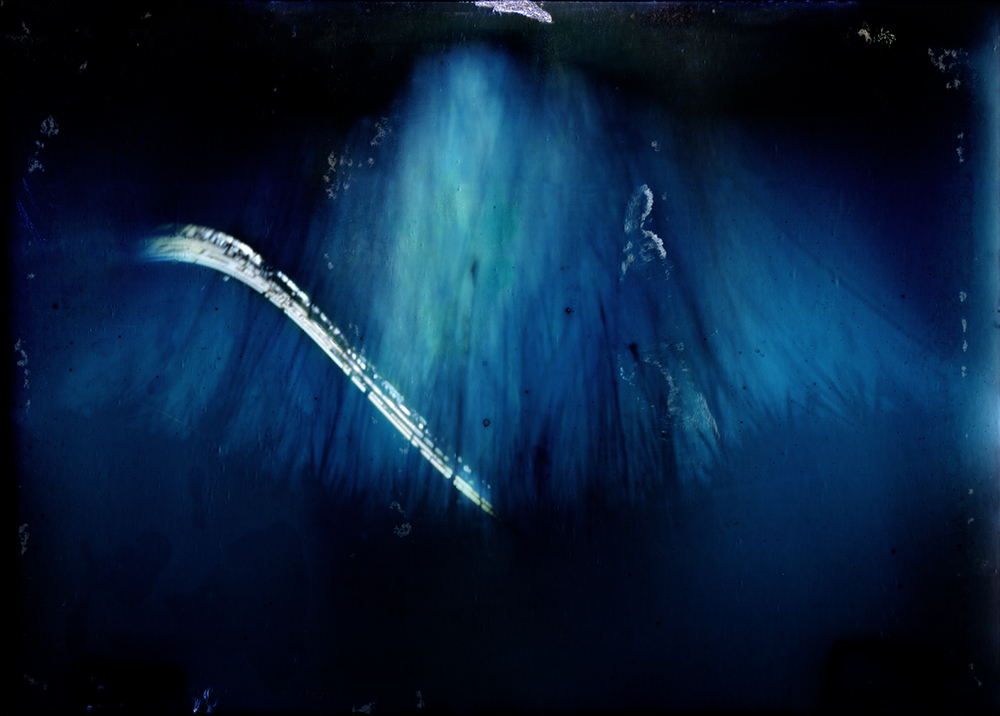

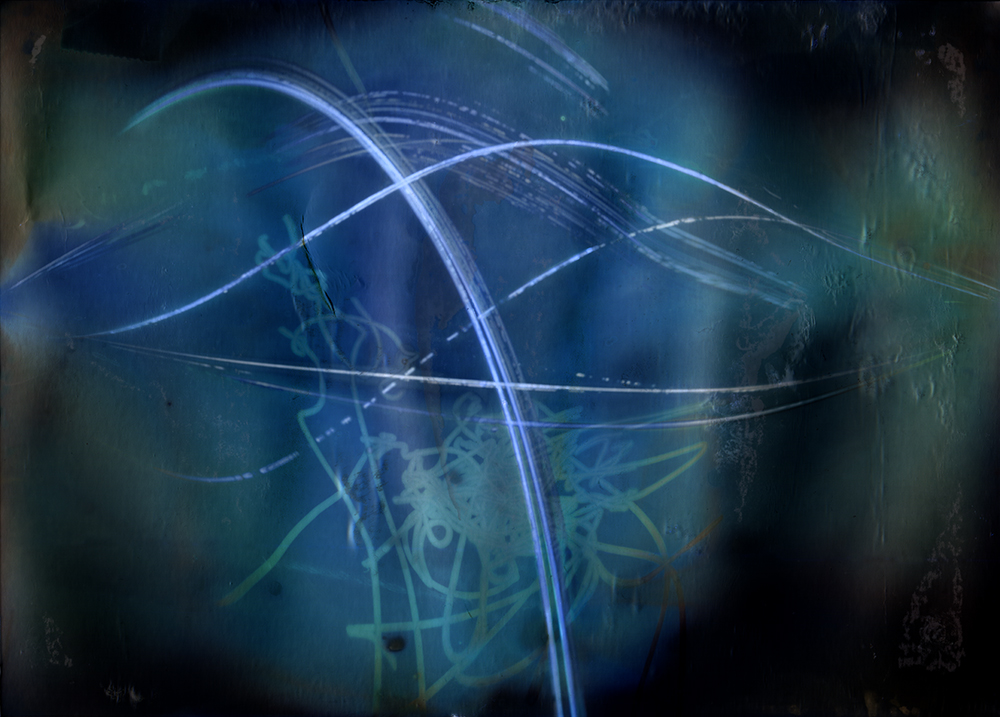

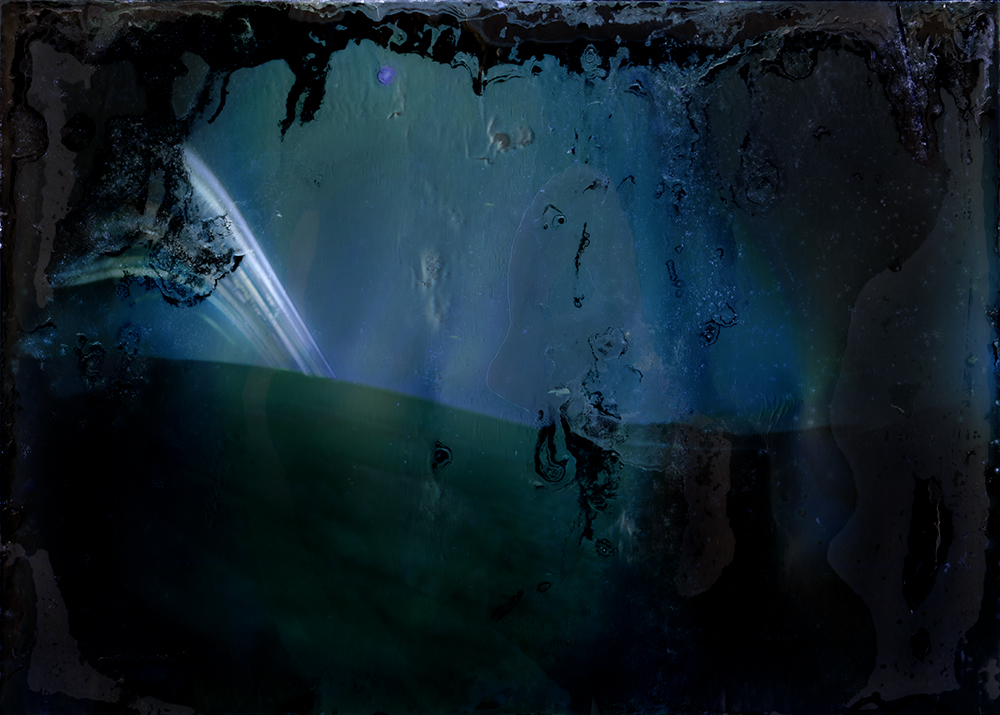

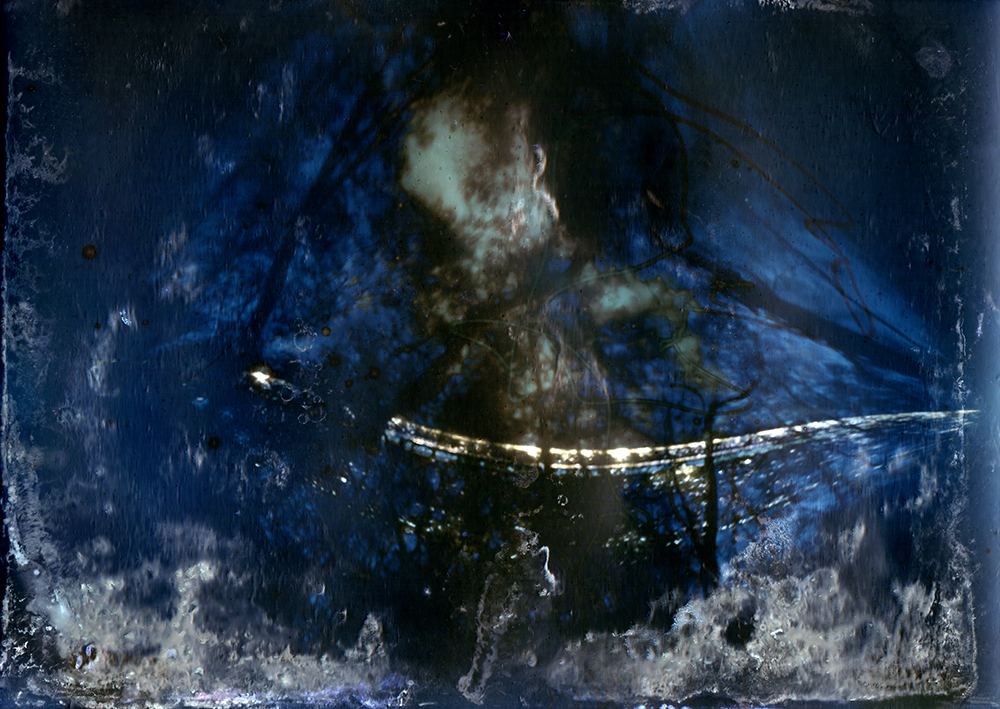

British photographer Al Brydon has a new monograph, Solargraphs, published by JW Editions in the UK that allows us to consider the world in new ways. The elements of time, surprise, and light are at the heart of his project, with some images created over a period of months. The beauty of this work is that combined with the disintegration of the film emulsion, the natural world becomes the artist. Light streaks in the form of brush strokes and sensuous color in tones of moody blues and greens result in painterly and magical images. His practice of time and place also allows him to experience time passing and to recognize life and death taking place outside of the artwork. Al stated upon finding one of his pinhole cameras, “New Solargraph. 4.5 months. I left this one in thick woodland. Upon my return it had all been felled. Unbelievably after an hour of searching I found the tin. What you’re looking at is the death of a wood.“

Al Brydon is a photographer based in the north of the UK working on long term photography projects. He has been published and exhibited both in the UK and abroad and is co-founder of the Inside the Outside photography collective. He’s interested in the history of landscape and human interaction and alteration of the landscape. The long departed people who have shaped that world sang songs that continue to echo. He’s slowly learning to listen.

Solargraphs

Solargraphs are pinhole cameras with exposure times measured in months rather than fractions of a second. This slowing down of time produces the arcs of the sun as it traces it’s way across the sky. The ‘how’ isn’t anywhere near as important as the ‘why but it gives you an idea of what’s involved in making the work. The length of time involved in raises certain questions. Is it a different me collecting the solargraph than the person who left it? Maybe a window into what the landscape looks like when I’m not there to experience it?

What’s implied in the image is as important as what you can see. Anything moving quickly isn’t pictured but is in there. Solargraphs see everything (metaphorically) like photographic black holes. Every moment of joy and sadness you have experienced while each exposure was made is in there somewhere. A newborns first breath and another person’s last. The chaos of the universe condensed into photographic form set within the confines of a 5×7 piece of darkroom paper. With Solargraphs we are able to experience time almost in a geological sense and gain a glimpse into a differing reality than our own. A looped reminder of how fleeting our lives are. – Al Brydon

About the Process:

I made the Solargraphs from empty beer cans. Below is a crude photograph of one. I would place a piece of 5×7 standard photographic print paper in the tin, tape it in place, pop the lid on and then gaffer-tape it shut. As simple as it gets. I would usually make a batch of them. It’s an oddly relaxing process. I then would look at my tins which had become pregnant with possibilities and thought about the next step. The Placement.

That next stage of the process was the best part. I originally made Solargraphs to unwind after finishing whatever body of work I’d been working on. They were a great way to mentally untangle myself. I’d put three or four Solargraphs in a rucksack, go to a place I love then just wander. The places I chose were usually out of the way. I didn’t want other people to find the cameras so I found myself in some remote, almost secret, spots. Even then some were found. Sometimes I’d return after three or four months and there would be nothing but a few scraps of tape on the floor. I’d almost find the missing ones more interesting than the ones I was able to collect. That bizarre interaction with someone or something in the process. Occasionally I’d find them intact but thrown into a bush or crushed. Sometimes the lids had been pecked through by birds letting the light and weather in. It was all part of the serendipity.

The locations were all over the place really. Some were in woodland, some in quarries and on moorland. The only stipulation for location was it had to be somewhere I wanted to be at that particular time. Each tin became an anchor point in the landscape. I’d sometimes go and check on them just to see if they were still there and then walk away again. I could have as many as ten of them all gathering light at any one time. It felt like they were all connected in a lattice or web and I was tending them like plants. And the longer I left them the more precious they became.

The exposure times for these cameras is measured in weeks, months and sometimes years, rather than fractions of a second. This slowing, this winding down, was one of the aspects of the process I found attractive. Due to the lengths of time involved in making the photographs it would essentially be a different me collecting it than the past version of me who’d left it. I started using them as barometers for life. Every bad thought, every smile, life, death, all the minutia of daily existence funneled down onto a 5×7 piece of photographic paper. I was also very interested in what wasn’t actually pictured in the Solargraphs. Birds and animals moving past it. My own receding footsteps as I wandered away to return at a later date. All these things moved too fast to be represented physically in the image but they were all in there somewhere none the less. I guess Solargraph images are how I think a tree might experience that ubiquitous human construct of time if it could. Another aspect was that I wanted to see what the landscape looked like after I’d left it and wasn’t there to experience it. Solargraphs made me very conscious of what I can’t see. That which is visible is the principle human source of information about the world. Photographs largely tend to be things we’ve seen that we felt were important enough to us to raise a camera to our eye and make a photograph. Except I can’t do this with a Solargraph. And the image I hope to make is not something I can actually see. Not with my eyes at least. However they are still photographs and are still essentially a copy of the death of a moment. With these cameras the moment just goes on for a little longer.

I have spent the last five years making these and now they have been put into book form. It feels like a good conclusion to the series.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025

-

Erin Shirreff: Permanent DraftsAugust 24th, 2025