Lauren Orchowski: The Observable Universe, Near and Far

The Observable Universe, Near and Far, by Lauren Orchowski, was selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview Lauren to gain further insight into this project.

The Observable Universe, Near and Far

In astrophysics the “observable universe” is recognized as a celestial sphere containing all matter that can be presently viewed from Earth. As humans, we make conscious and subconscious decisions regarding the extent to which we contemplate our world beyond our immediate natural and constructed environments. This series explores our individual and collective relationships with astrophysical environments, the macro and micro spaces that surround them, and photographic terrain encompassing art and science. This has led me to me to consider the tangible spaces we inhabit near and amongst each other and how our existence is paralleled by the infinitely far-reaching horizontal and vertical axes of Earth, the atmosphere, and cosmos.

I draw on my childhood geographical relationship of growing up next to a quarry that shared the land with my house in the Hudson River Valley of upstate New York. The reality of a vast human made crater increasingly falling below sea level with every blast was a concept I found difficult to comprehend. Thus it was my first introduction to the idea of humans taking what was a natural resource and manufacturing it for other uses in the form of a road or runway used for travel. My perspective of time also registered as my knowledge of how many thousands of years were needed for the Hudson River Valley to be carved by glacial activity in contrast to the way the quarry’s exponentially deepening, unnatural shape took form.

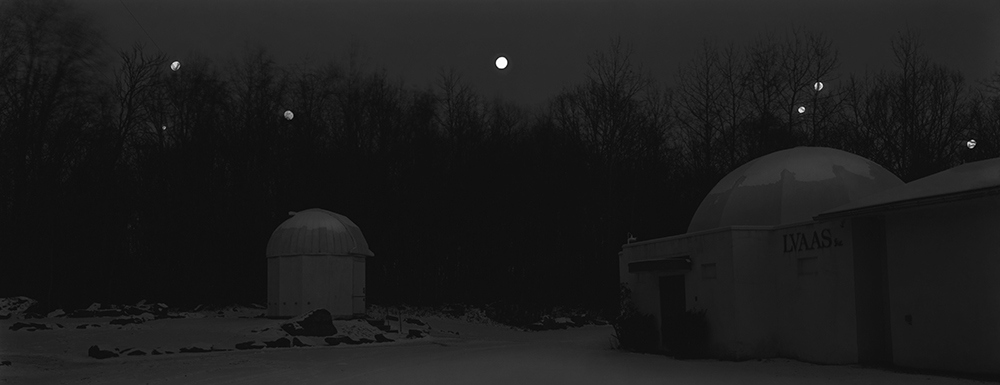

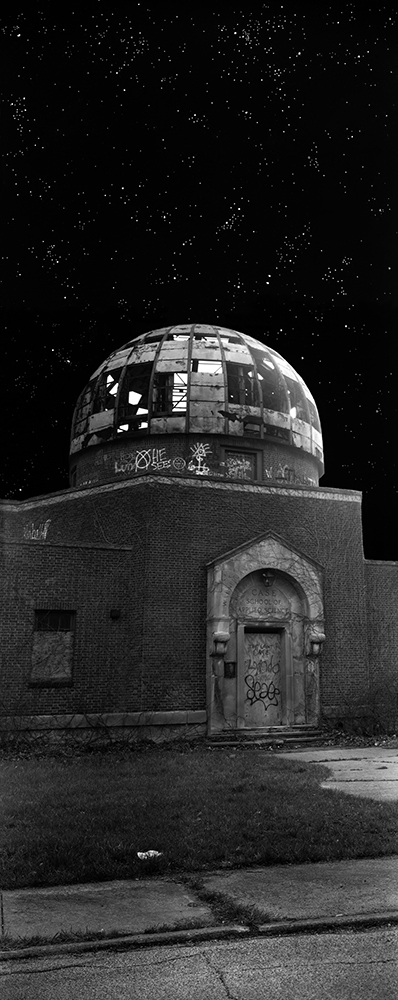

Beginning an investigation into how vertical space is interpreted and used from any depth became increasingly urgent to me as the depletion of the night sky became more apparent. I began documenting observatories across the United States aware of the rapidly evolving scientific landscape that is under constant threat by our planet’s current political and environmental state. Many of the locations are at a high altitude surrounded by significantly less atmosphere and are quite remote. This renders the sky less polluted by artificial light allowing for a level of darkness close to antiquity. This metaphysical process intuitively leads me to return to document what is closer to my everyday existence. To record these environments I use a 7” x 17” ultra large format view camera. It is only during the darkroom process after hand developing the film and contact printing the negative, that I begin to understand the environment I’ve photographed as well as what has not been recorded on the negative. I consider the Charles and Ray Eames American short film “Powers of Ten” and Buckminster Fuller’s concept of “Spaceship Earth.” Ultimately it is with the application of memory, chemistry, and a desire to communicate the evidence of time on a singular sheet of photographic paper that allows the past, present, and future to emerge.

I imagine these photographs being used as future historical documents by a civilization from some counter Earth as a narrative of visual specimens of what was the collection of spaces on our planet. Examples of night, the built structures we used to try and contact celestial neighbors, and the elements of our immediate environments that both enchanted us and rendered us extinct.

Daniel George: Some of your images make connections between familiar locales and distant galaxies (“Constellation” comes to mind). What initiated this way of seeing?

Lauren Orchowski: One of the first images I made in this project was “Constellation.” It is a cinder block wall housing an astronomical observatory that is painted with a depiction of the cosmos. Shortly thereafter I began to re-explore and photograph the quarry and surrounding area that was by my childhood home in upstate New York. As a kid, I’d ride my bike through the giant mounds of rock which resembled another planet or moonscape and later on, a black hole. After making images of the quarry I placed them next to the “Constellation” wall photograph and what emerged was a recognition of two forms of natural resources (geological and sky.) The wall of the observatory was constructed from rock that came from a quarry much like the one I’d ride my bike on as kid. The idea of “near and far” also came to me very early on as I drew parallels beyond examining physical space and began considering the concepts surrounding spectral light such as in the image “School of Applied Science” and in the fireflies photographs.

DG: Your photographs show an obvious interest in, and affinity for dark skies. How does this contrast your everyday experience living in New York City?

LO: Yes, there can be quite a contrast! My every night experience is one of looking up and seeing very few, if any celestial objects and stars. If I’m lucky I’ll get to see certain planets or the International Space Station flying over the island. Currently, the New York CIty night sky ranks a 9 on the Bortle scale which measures night sky brightness, 1 being the lowest and representative of an excellent sky for viewing celestial objects. In my apartment I’ve got black out shades to prevent the City’s glow from keeping me up at night and I even live in a “darker area” of the city. I carry this experience of not being able to see an idealized night sky where I live into the darkroom and my studio practice and I revel in the absolute darkness of the room required to tray process my sheet film. With the intense commodification of air rights and the development of vertical space for private residences and businesses it will be interesting in the future to see how we govern ourselves and others with regards to light trespass and the ability to even see the sky during the day let alone the night when looking directly up.

DG: Generally, I do not ask camera questions, but 7×17 is such a distinct format. It generates an extreme sense of upward movement, most notable in your vertical images. What is it about that format that lends itself to this project?

LO: Using a 7×17 was a natural transition because I’d been using an 8×10 for many of my previous projects that focus on space and sky. I wanted to continue using what I considered to be a straight forward photographic machine; the view camera. Having already possessed a familiarity with my equipment I could concentrate on the content of the series. With this project it is necessary to document and create an immediate sense of expansiveness to the the viewer and the use of the 7×17 negative size accommodates the amount of information I want to capture from the subject matter. And, I also recalled from my childhood science classes, the vertically oriented renderings and diagrams of the layers of the atmosphere surrounding Earth, with which I was always obsessed. Using this analog set up has worked well in locations such as Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia which is a National Radio Quiet Zone where using any equipment that requires a battery is forbidden because to do so will cause interference with the research being conducted.

DG: You mention that once the negative is developed, you better understand the environments that you record. What emerges in these images that you did not see before?

LO: Some environments I only have a brief period of time to work within such as the experience of exposing the film for the image “Crescent Sun” made during the solar eclipse of 2017. There were so many nuanced environmental factors from the changing light in the sky to the sounds closest to the ground, that my immediate surroundings were bewildering. There was also an otherworldly illuminated yellow cast obscuring any literal comprehension of black and white details until I could reveal them much later at light table with a loupe after developing my negatives.

Other environments have been familiar to me for many decades such as “Upstate Sun” made on the now nearly vacant grounds of the IBM manufacturing plant where my father worked for 36 years. All I could think of when I was making that image was the Charles and Ray Eames 1977 short film “Powers of 10” which was funded by IBM, intended to foster an interest in science in America’s youth, and was played repeatedly on local access TV among other venues when I was growing up. After I began working with the first contact print of that negative what emerged was a profound sense of loss generated from the recent death of my father combined with an overwhelming fear for the direction our planet is heading environmentally. To reconcile those emotions I incorporated visual aspects from the memory of that film and the night sky in place of what I viewed as void in the negative.

DG: Why do you feel it is important to highlight the relationship between humans and the astrophysical environment?

LO: With the astrophysical encompassing so many areas of study and the imagination I feel that I can draw attention to how humans relate to it, simultaneously bringing forth many other vital conversations concerning issues for which time is the critical foundation. Observing how we exist within and against these landscapes (whether they are used for scientific research or escapism, from collective or individual viewpoints), provides for an understanding and allows us to reevaluate our position on Earth and in the universe to survive as a species.

Lauren Orchowski’s photographic practice is driven by the desire to document and re-envision our relationship to astrophysical environments and the night sky. She approaches the privilege of seeing with an unwavering respect for how we experience and perceive the spectral shifts of light and darkness and their impact on the human condition. Her images are made by creating analog film based photographs with 8” x 10″ and 7” x 17″ large and ultra large format cameras. Having received her first Instamatic camera in 1982 at the age of 7 she began her obsession with documenting her surroundings. From there she moved on to working in an analog darkroom at 15, and proceeded to earn a BFA from Arizona State University and an MFA from Hunter College in New York City, both in photography with additional studies in Visual Communication at the Universität der Künste in Berlin, Germany.

Her work is represented in several collections including The Bienecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, The Rutgers Archives for Printmaking, The George Eastman House, the Annenberg Space for Photography, The International Center for Photography Library, and has been reviewed and featured in publications such as The New York Times, Scientific American, Gizmodo –(France, United States, and Australia)”, and artcritical. She has exhibited on the International Space Station and more locally on Earth at Site Gallery, Brooklyn, New York, the Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, Newspace Center For Photography, the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, and the Minnesota Center for Book Arts. In 2010 her self-published ongoing documentary project “Rocket Science” was selected by Darius Himes as the Second Runner Up in the Portfolio Category of The International Photo Book Now Competition. Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, she lives and works in New York City.

The Observable Universe, Near and Far was recently selected by Rebecca Morse for the PHOTOGRAPHY – SHORTLIST for the FOTOFILMIC MESH award, and will be included this fall in the Rust Belt Biennial at the Sordoni Art Gallery of Wilkes University.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026