Fritz Liedtke: Sacred

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Sacred by Fritz Liedtke.

Fritz Liedtke began photographing as a teen, carrying his Kodak 110 Instamatic around on a US tour with his father at age 14, in their little blue Datsun B210. Twenty-five years later, he continues to explore the world, camera in hand.

Fritz holds a BFA in photography and printmaking, and has won numerous awards, grants, and residencies for his work. His images have been widely published by magazines such as National Geographic, Lenswork, PDN, Professional Photographer, View Camera Magazine, Rangefinder, Silvershotz, PhotoLife, Diffusion, and blogs such as Lenscratch, Photoeye, LensCulture, F-stop, and others. His work is held in such collections as the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Griffin Museum of Photography, The Haggerty Museum, Portland Art Museum, Yale University Library, Lishui Museum of Photography, Scripps College Rare Book Collection, and more.

Aside from making art, Fritz enjoys creating unique images for his commercial and editorial clients, traveling, and teaching workshops on photography and the artistic life. He is constantly looking for new ways to approach the world through art.

Fritz and his family call Portland, Oregon their home. They live on several acres outside of town surrounded by herons, egrets, ducks, and bitterns. And a few frogs.

SACRED sā-krəd

2b: entitled to reverence and respect

In America’s current climate of divisiveness and moral outrage, how does one respond with something better than a tweet? How do we stand up for the powerless? How might we reverence, honor, and dignify those who are often vilified and marginalized in 45’s America?

Perhaps it’s time to answer these questions with something other than words. In my own quiet way, these images are my response.

I spent several months listening to and learning from the friends depicted here. I had to ask myself: what do I, a hetero, cis-gender, middle-class, white male, have to say about transgender people, Muslim women, Latina farm workers, young black men, or Native Americans? The answer: that we are one. That each person has a rightful place as part of the beloved community. I wanted to show that love trumps divisiveness, apathy, race, gender, politics, class, ignorance, fear, and hate. That when we take the time to know one another, to listen and learn, we become more.

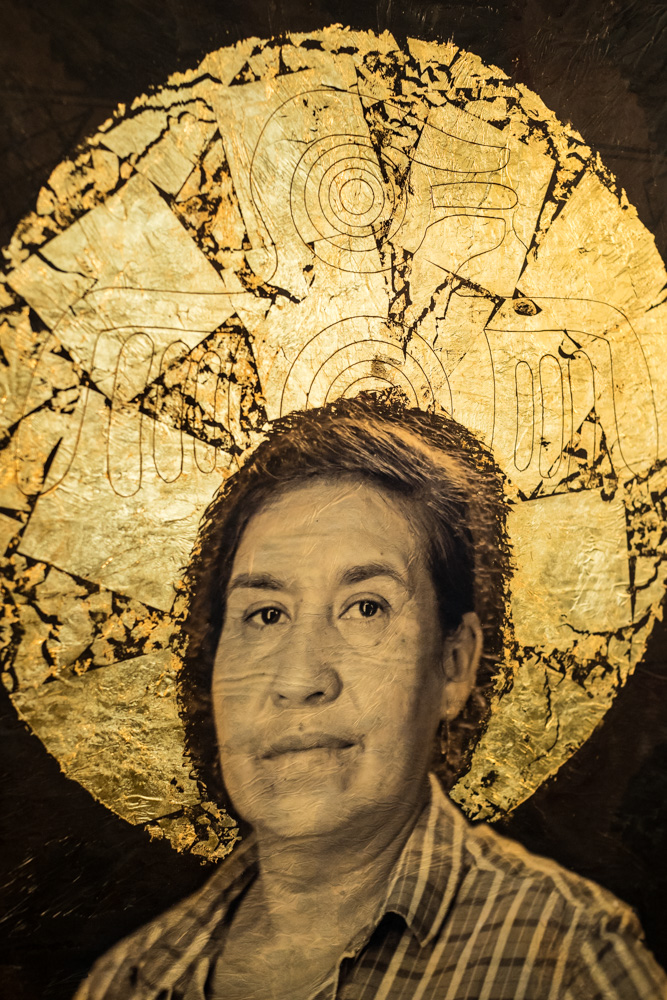

So we collaborated to create images that celebrate their history, identity, humanity, and courage through traditional symbolism. In spite of its religious undertones, iconography remains a valid way of speaking about that which is holy–that which we care deeply about, hold dear, consider beautiful and sacred. This type of language is deeply needed today.

This set of 5 large photo-encaustic panels together create one body of work. They are crafted of layers of wax and metal, wood and paper, ink and paint: many different elements that create a whole. E pluribus unum.

These people are my brother, sister, mother, father. And they glow from the inside out. As Michael Golz explains, “The subject of the icon is a person transfigured by…love.”

Each of these pieces is a 24”×36″ photo-encaustic assemblage. They are composed of metal leaf, gold leaf, paint, ink, and paper, on a cradled 1.5″ wood panel. Each piece is unique, requiring many days to create.

Daniel George: In the beginning of your artist statement, you ask a series of questions that many of us grapple with—prefacing the work as your personal response. Tell me more about the role of your work in this context. Why did you feel a visual response was best?

Fritz Liedtke: Just yesterday I was speaking with a friend about how we’ve both had to step away from the news and from social media in significant ways, because it’s just too painful. No amount of talking with people of different viewpoints seems to sway an argument; facts don’t seem to matter anymore. But I still feel responsible to stand up for what I see as true, wise, and good. So I turned to visual art as a way of creating (what I hoped would be) something compassionate and engaging, that could speak in ways that words do not. Something that might be heard with the heart rather than the head. It felt good to do something–to make something with my hands–rather than just throwing my hands up in frustration and anger.

DG: You also mention that collaboration played a central role in creating these images. What did that effort look like?

FL: The first bit of collaboration in the process was finding the subjects. I wanted to work with a Muslim woman, a transgender person, a Latin American farm worker, a Native American, and a young African American man. I wanted to span a variety of ages as well as genders. So finding the right people was challenging; I networked with friends and clients to come up with the right people to photograph for the project.

Then I had to work with these 5 people (and the friends that introduced us) to coordinate shooting, clothing, and, later, the symbolism for each piece. Because I am not a part of any of these cultures myself, I wanted to be sensitive about how I represented them, and my subjects were often helpful in pointing me in the right direction.

DG: I was struck by the quantity of symbols you included, and appreciate the detail shots when viewing the work online. What was the process like determining which to include, and what further insights would you provide as to their significance?

FL: I did a lot of research, looking for symbolism that worked graphically (did it fit the shapes and spaces I was working with in the composition?), culturally (is it from or representative of the culture of the person?), and thematically (did the symbol have meaning related to what I was saying about the person?). For most of these I had to go back hundreds of years, to find symbols from their culture that worked on all three levels. Some of the primary symbols I’ve included are:

Transgender:

The Celtic Spiral is a symbol of growth, birth, and expansion of consciousness. It turns out that my subject’s family is of Irish ancestry, so this symbol fit in nicely on a number of levels.

Chemical symbols for estrogen and testosterone are included on his arms, as he mentioned to me that he’d had a temporary tattoo of testosterone at one point in his journey of transformation.

Muslim Woman:

We couldn’t find any particular symbolism in Islam for feminism or the strength and power of women. Instead I used some of the complex and beautiful patterns found in Islamic art, showcasing hundreds of years of Islamic history and artistry. I also included Arabic calligraphy for ‘Peace be upon you.’

Young African American Man:

For this piece, I wanted symbols that related to the courage and strength it takes to be an African American–to be who you are in spite of what society throws at you. I used three:

-

Nanse Ntontan in the halo: an African Adinkra symbol for wisdom, creativity, and the complexity of life.

-

Dwennimen: another Adinkra symbol that depicts ram’s horns, representing a mixture of humility with strength.

-

African Warrior’s Belt pattern: represents courage and bravery.

Mexican-American Farm Worker:

Reaching back to the Aztecs, Incas, and Mayans, I utilized two things:

-

The Aztec eagle (still used in the Mexican flag), which represents power, courage, and strength.

-

Traditional Inca and Maya patterns from period pottery, representing an astounding 1500 years of culture in Latin America.

Native American Woman:

This young woman is Navajo, and her family explained to me how important both the number 4, and the Navajo Spider Woman stories, are to them. I included 4 Spider Woman crosses in the background, and another in the halo. She is also wearing traditional jewelry from her grandmother.

DG: Each of these pieces is unique, and requires a labor-intensive process to assemble. Why did you feel it was important to utilize these materials?

FL: I’ve been combining encaustics with photography for the past 8 years, and I love that it gives me the ability to layer imagery, texture, and color. For the Sacred series, I wanted to utilize this ability to combine portraiture with metal leaf, etching, painting, drawing, and more. (For this project I also wanted to work big, making each piece 24 x 36”, for a total of 3 feet by 10 feet when the whole set is hung together.) I also wanted to reference classical iconography, and its texture and materials. As a result, the pieces are large and layered, and the more you look at them, the more you see.

DG: I get a sense that throughout this project, given the participation and role of your subjects, you discussed themes including community, family, and inclusiveness (among others). What sort of new or heightened awareness do you have now that you may not have had prior?

FL: I was grateful for the opportunity to sit down and talk with a variety of people that I may not have had the chance to get to know otherwise. A friend of mine introduced me to the Muslim woman I photographed, and we sat and talked for an hour over coffee about her life in Afghanistan, her immigration to America, her struggle to raise a family and go to school. I was able to spend more time with Native Americans and transgender people, and hear more about their stories. I love how photography gives me these kinds of opportunities, at home and around the world, to know people who are unlike me. I hope this series does the same for others–sparking conversation, empathy, compassion.

Just today I read a quote from Tim Urban: “I think humans can only feel real hatred of people they’re able to dehumanize in their heads. As soon as someone is exposed to reality and reminded of the full humanness of someone they hate, the hatred usually fades away and empathy pours in.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Binh Danh: Belonging in the National ParkMarch 4th, 2026

-

Vaune Trachman: Now IS AlwaysMarch 3rd, 2026

-

Amy Friend: FirelightFebruary 25th, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026