Andre Ramos-Woodard: a mediocre-ass nigga

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series a mediocre-ass nigga by Andre Ramos-Woodard.

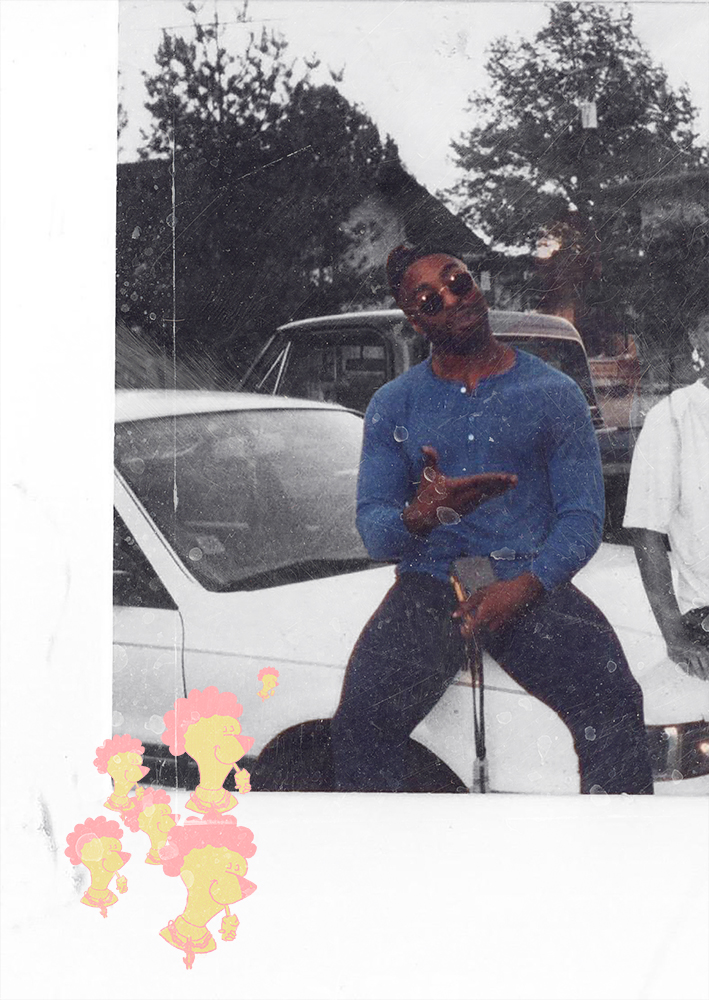

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, Andre Ramos-Woodard is a contemporary artist whose works evoke feelings of dreams and surrealistic narrative. Primarily working with photography and collage, he conveys ideas of communal and personal identity through internal conflicts. Ramos-Woodard is influenced by personal experiences he went through while discovering his own identity – he is queer and African-American, both of which are well-known targets for discrimination. He uses his art to accent the ideas of separation between him and the viewer, specifically those that may not resonate with the ideas of the “Other” or problems within minority groups in contemporary culture. Ramos-Woodard received his BFA from Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, and is currently pursuing his MFA at The University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

a mediocre-ass nigga

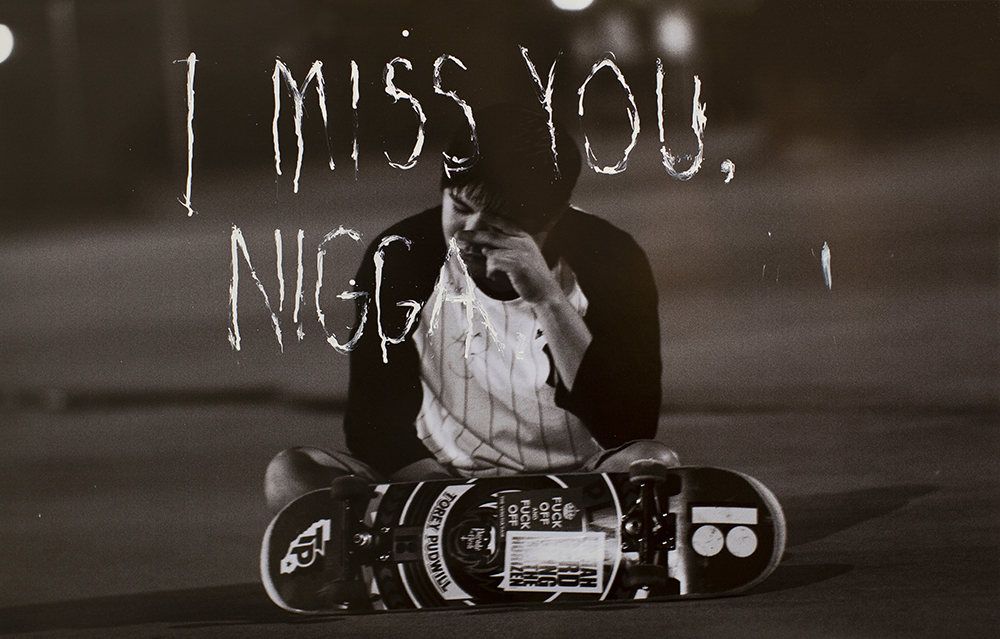

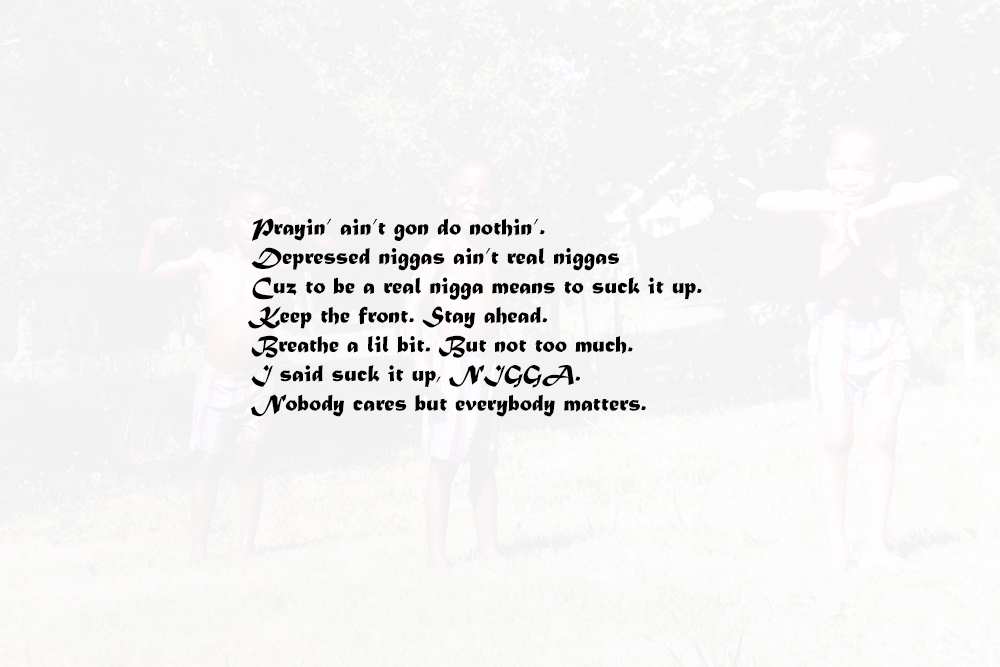

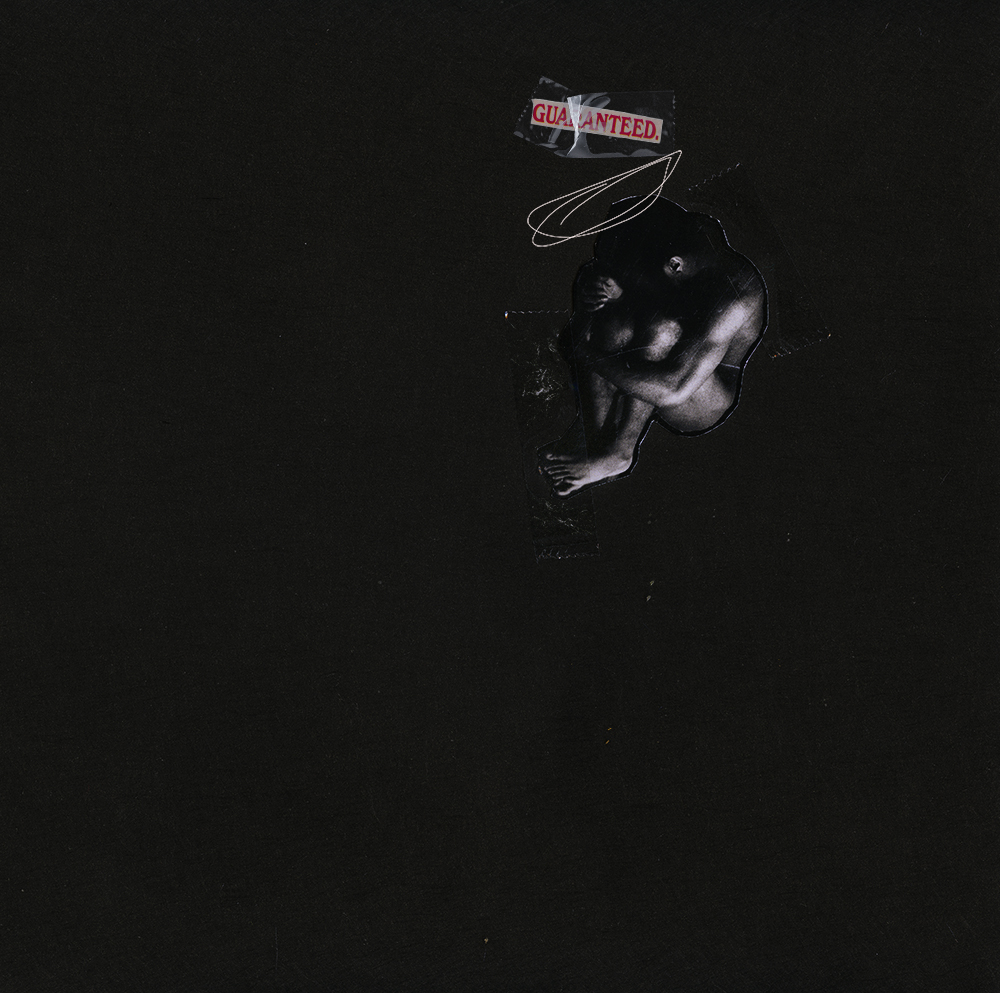

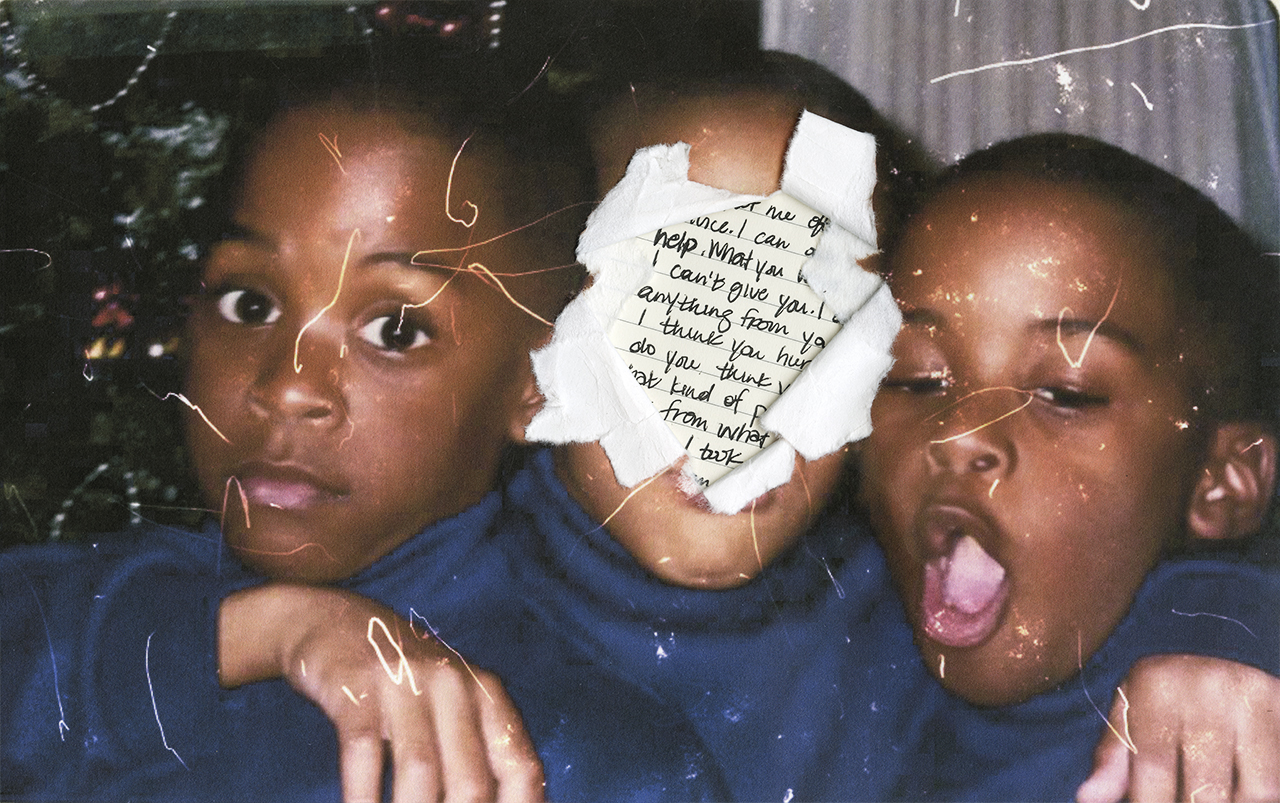

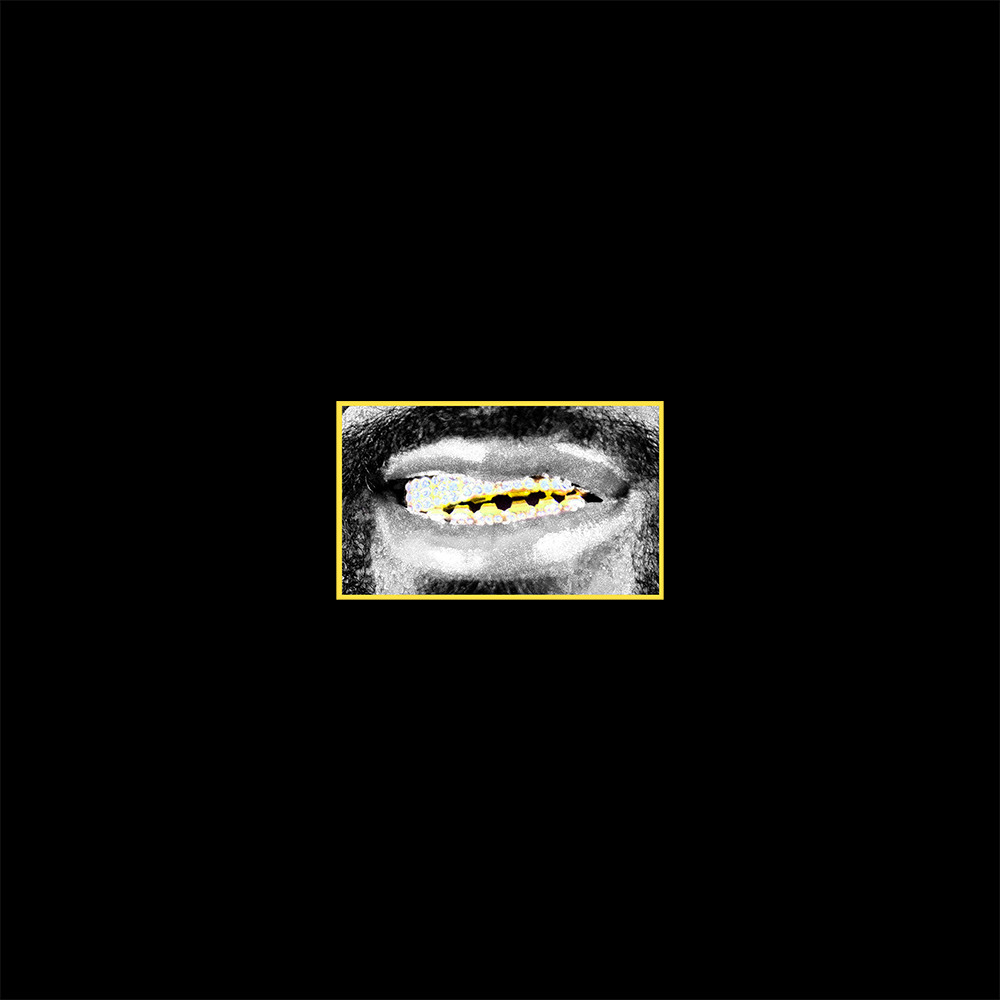

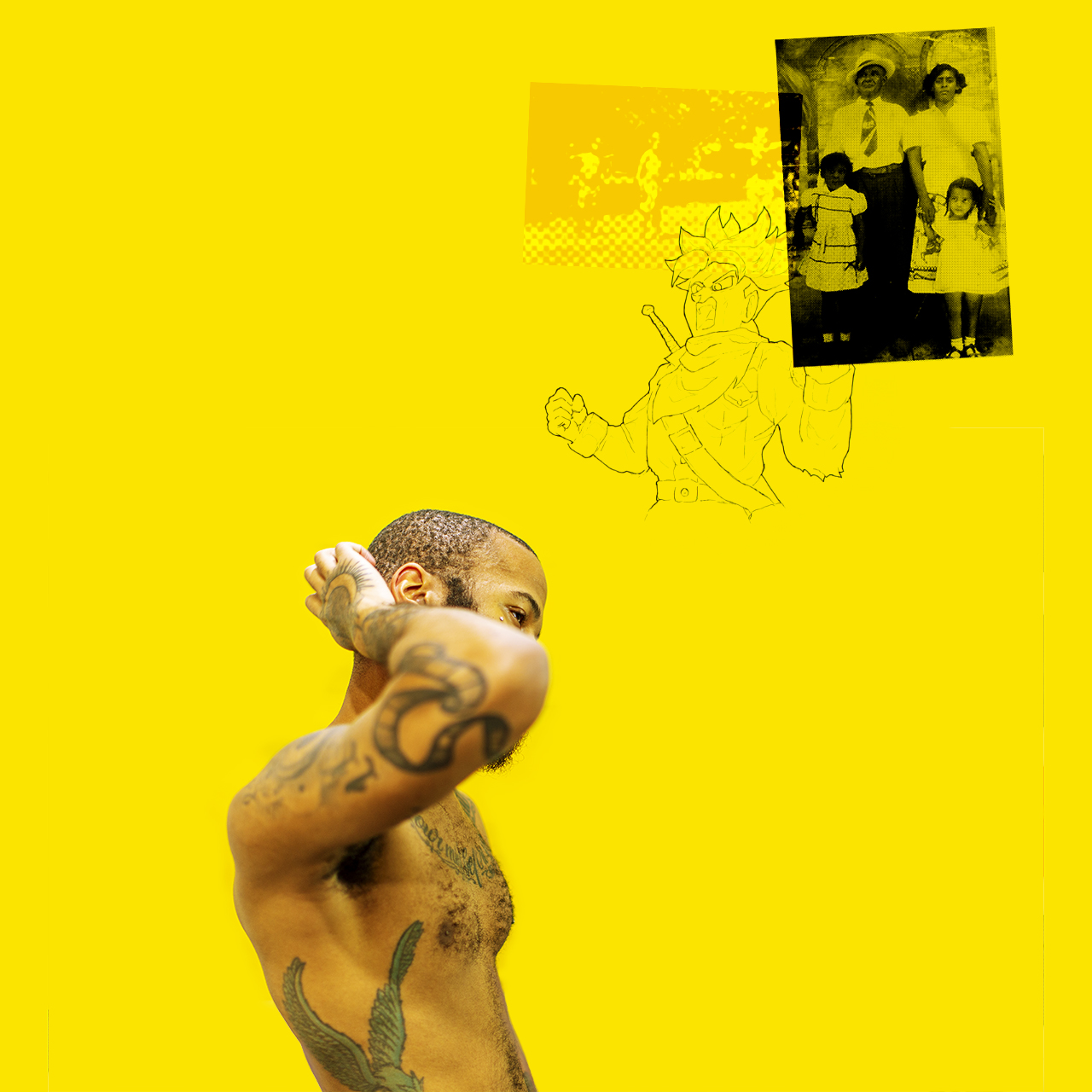

“a mediocre-ass nigga” is plain and simple a body of work about me. It’s about who I am to myself and the outside world. It’s about how I’m perceived because of the color of my skin. It’s about my beautiful black family. It’s about depression. It’s about microaggression, and stereotypes, and niggas getting shot for no reason. It’s about missing my grandmother. It’s about skittles and dark hoodies. It’s about the n-word. It’s about being home. It’s about memories. It’s about Goodlettsville, Tennessee. It’s about what I see in the mirror. All of this is about me.

Daniel George: Your work often deals with self. What interests you in autobiography? And what persuaded you to create your own—in the form of this specific project?

Andre Ramos-Woodard: Autobiographical work has always been the most successful way for me to explore and interpret my thoughts. I think this stems from the fact that I did not fit the stereotype placed upon me as a Black man growing up: I was a queer, Black youth in the South listening to Paramore who loved photography and art, and for some reason I found that society went out of its way to emphasize the apparent abnormalities and contradictions that made up my personality versus my complexion. The older I get (and I know I’m still a kid), the more I discover about my own identity and the historic precedents that have come to influence how I’m perceived.

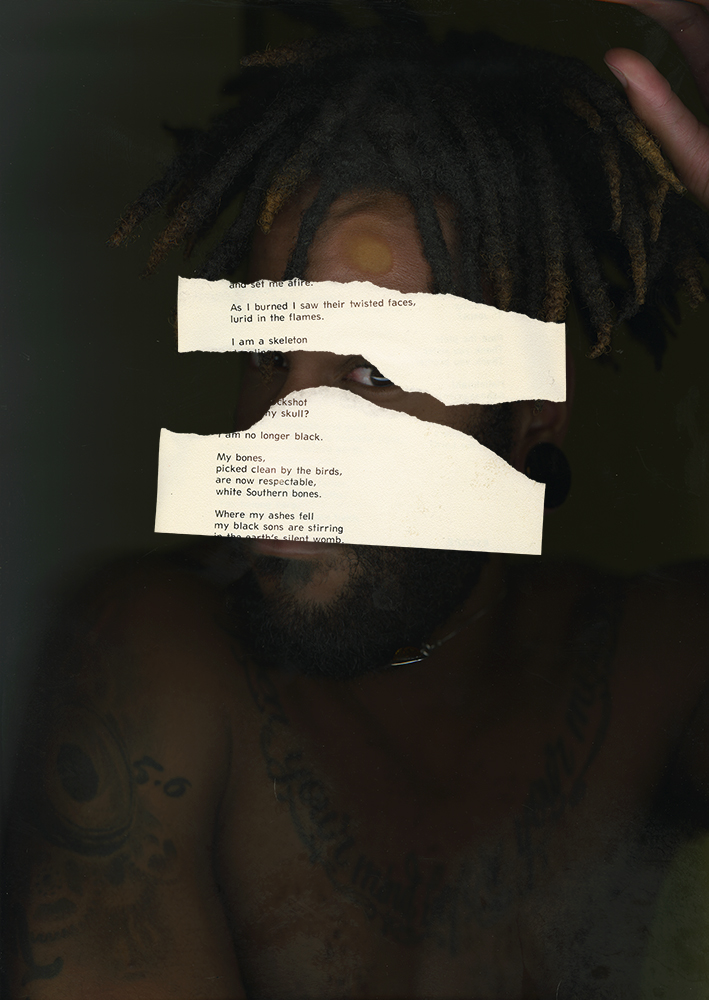

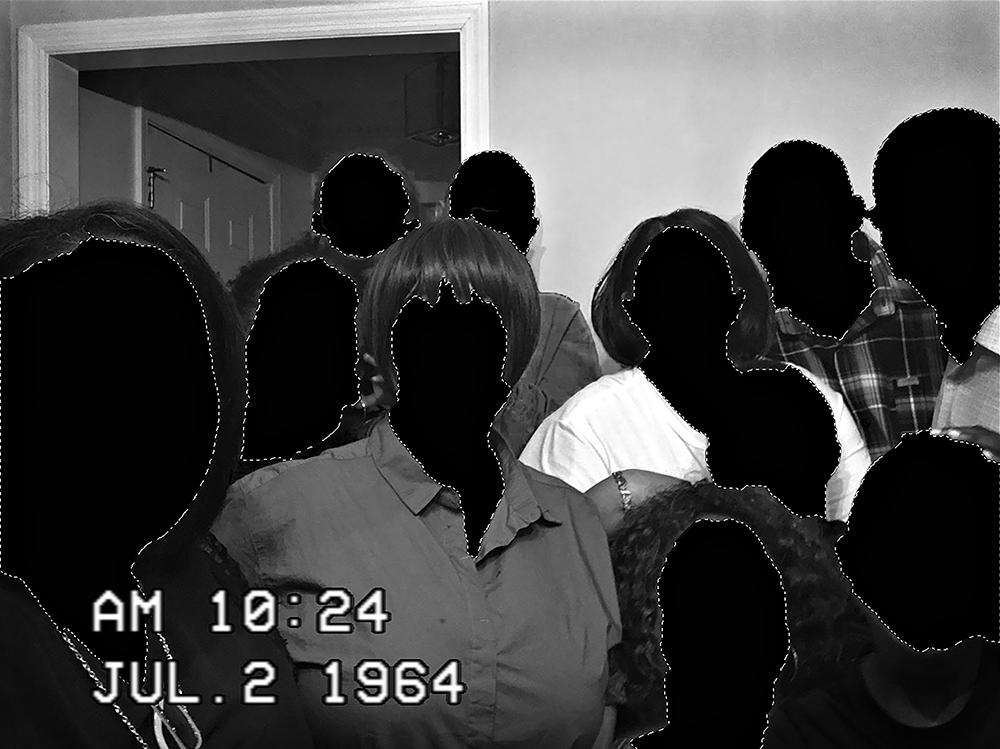

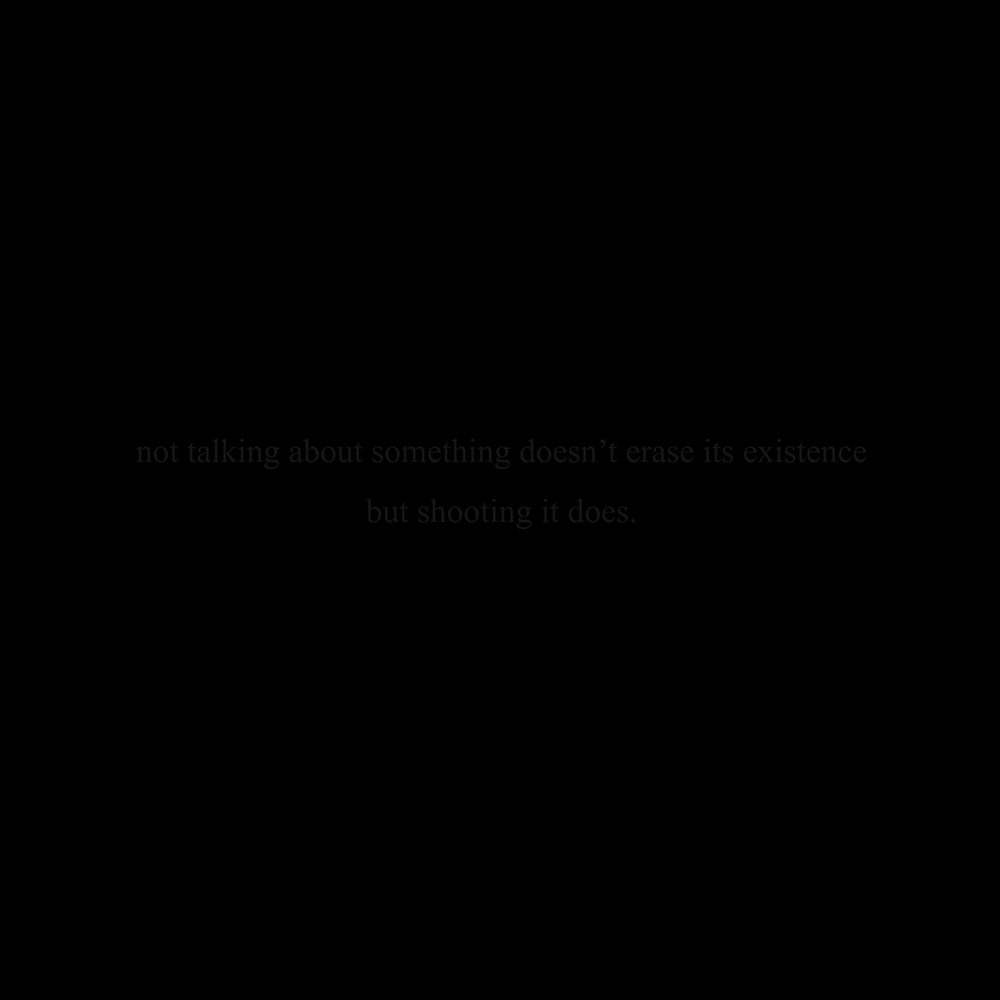

“a mediocre-ass nigga” manifested when I started doing some in-depth research on Black culture, police brutality, and the history of Black people in America. There was something incredibly internal about that experience that slapped me in the face. As I was finding all these things out about my history and the society I exist in, I found that the data and evidence of numerous accounts of brutalization and racism against Black bodies is unnecessarily astronomical. I still find it impossible not to feel pain in response to that. At first I was confused at the magnitude of my emotional reaction to the stuff I was finding out, but this project helped me validate my responses and comprehend why Black pain and rage is so valid.

DG: Your use of collage is reminiscent of a journal or notebook, and creates a very engaging narrative—as if you are assembling bits and pieces of identity based on personal and communal perceptions. Why do you feel this approach best weaves together the intricate notions of self that are addressed in your work?

ARW: Collage allows me to overlap the various aspects of my experience and identity. Regardless of the communities that I identity with (Black, queer, etc.) or how many experiences I have that are shared with other people, no one can literally see the world through my eyes. There will always be differences in my direct experience with life and another person’s. I try to incorporate visual elements that accent different feelings and experiences: from memories in my childhood to influential anime characters, from societal ideas of masculinity to the ideas of the Black experience versus my Black experience. For me collage works as a successful representation of the idea that there are many pieces that make up my personhood. I’ve also recently felt like confining myself to making in only one way is a little disingenuous to all my thoughts and emotions. Some things are easier to get across by making a photograph, others by drawing or mark making, and others by writing or text. I try not to confine myself to a particular medium or material and have slowly been expanding my comfort zone as far as mixing media.

DG: Tell me more about your use of text in the dialogue of this project. It makes me think about the power of language, and how, as a form of communication, it contributes so heavily to one’s identity. I see evidence of stereotypes along with expectations, and wonder how all this relates to your experience of self-discovery.

ARW: There are obvious ways in which language has impacted the stereotypes of Black identity, like the n-word and the ways people view Ebonics or ‘Black speech’, but I also question the reasoning behind some of these negative connotations to Blackness. Why am I looked down upon in some places for using ‘Black speech’ but expected to in others? What does it mean when someone says I ‘speak white’? Questioning helps lead me to a sense of self-discovery. You are so right about how language can contribute to how someone forms their identity. After all, I can’t remove the skin I have, nor can I remove the historical context the n-word has to that same skin. But I can recognize these facts, understand and learn from history, and in the case of the word “nigga” for Black people, reclaim and recontextualize it.

DG: I’ve been thinking a lot about the second sentence in your artist statement in light of current Black Lives Matter protests and renewed national attention given to the ways in which Black Americans are perceived because of the color of their skin. It reminded me of the recently circulated video of a 10-year-old boy playing basketball in his driveway, who tucked himself out of sight as a police car drove by. He was simply playing as kids do, but felt the need to hide anyway. Even at his age, he recognized that others will erroneously judge him as a person of color. Would you mind expanding on this theme further—of navigating self-perception with the misguided views of others?

ARW: The video you’re referencing spoke to me as well. The fact that a child who is only 10 years old can recognize that he is not safe in the skin he’s in is both relevant and tragic. In fact, he’s considered a threat in America—a country that has not only grown from systemic anti-Black oppression, colonialism, and othering, but has also hidden these perpetuated problems from its people. Black people have to teach their kids to act in a specific way when confronted with the police because they know how it is (and thanks to video cameras and smartphones, more than just Black people are starting to know how it is). Even if that kid is too young to completely understand the intricacies of race and racism in America, he surely understands enough about the world he lives in to know and feel that he is not safe when confronted with the police. Their authority and privilege when matched with the simultaneous fear of and terrorization of the Black body has so often led to death that it makes any altercation incredibly anxiety inducing.

Now knowing that this sort of experience is simply a piece in the puzzle of Black discrimination, it’s easy to see why racism and stereotyping makes navigating personal identity even harder than it already is. It’s not fair that little Black kids playing basketball on their own property feel that sort of fear. These sort of happenings—innocent Black kids feeling enough fear to hide in the presence of police—is not uncommon. The Black Lives Matter movement has been trying to shed light on these experiences for a minute now, and I think and hope people are really starting to wake up to these sort of injustices. I will say though, I have found some success in uncovering my identity in the midst of all the chaos. Since I didn’t learn much in history classes about my Black origins I have done a lot of educating myself. I love my Black skin and my Black identity, and regardless of the negative stereotypes unjustly placed around it, I find solace in that and happiness in my Blackness. I can confidently say that, at the very least, oppression will not diminish our pride. Black people have proven to be so strong when facing the systems of power pitted against them.

DG: This work deals with heavy topics, including depression and racism, and your biography indicates that as a queer African-American, you have faced discrimination from various fronts. In what way does your artistic practice aid you in confronting these topics?

ARW: Not to be too cliche…but art has been pretty relevant in my life from a young age. I started drawing (badly) when I was a kid and taking photographs as a teen after I moved to Texas, and my interest in those practices never dwindled once I picked them up. Art making was not only intuitive and enjoyable though—it came to be the best way for me to really confront and cope with the internal struggles of mental health and discrimination. On the worst days, I find it difficult to elaborate on the severity of these issues without getting overwhelmed or emotional. I can step away from those problems a bit when I’m in the studio. Art allows me to deal with these thoughts in the privacy of my head; a safe space. I can express both the highs and lows of these topics. I can convey my experience how I see fit and at my own pace. While I do believe that things are changing for the better regarding these topics, I know that there are many negative stigmas around mental health and that talking about discriminatory experiences can be triggering at times. I really hope to positively contribute to these long overdue conversations that many people are starting to bring up now. My practice allows me to highlight these relevant topics in the most genuine way I know how.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Martin Stranka: All My StrangersDecember 14th, 2025

-

Interview with Maja Daniels: Gertrud, Natural Phenomena, and Alternative TimelinesNovember 16th, 2025

-

MG Vander Elst: SilencesOctober 21st, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Josh BirnbaumOctober 10th, 2025

-

Aiko Wakao Austin: What we inheritOctober 9th, 2025