Ashley Moog Bowlsbey: Second Skin

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these individuals to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are looking at the series Second Skin by Ashley Moog Bowlsbey.

Ashley Moog Bowlsbey is an artist from southern York County, Pennsylvania. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in photography from Pennsylvania College of Art & Design in 2012. Then in 2017, she completed her Master of Fine Arts in photography from Indiana University Bloomington. She is currently an adjunct professor of photography at York College of Pennsylvania. She specializes in both analog and digital photography, along with several bookmaking and printmaking processes. Ashley’s work is emotionally driven, often focusing on topics of family, home, loss and personal struggles. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in locations such as Philadelphia PA, Washington DC, Pingyao China, Daegu South Korea, and London England.

Second Skin

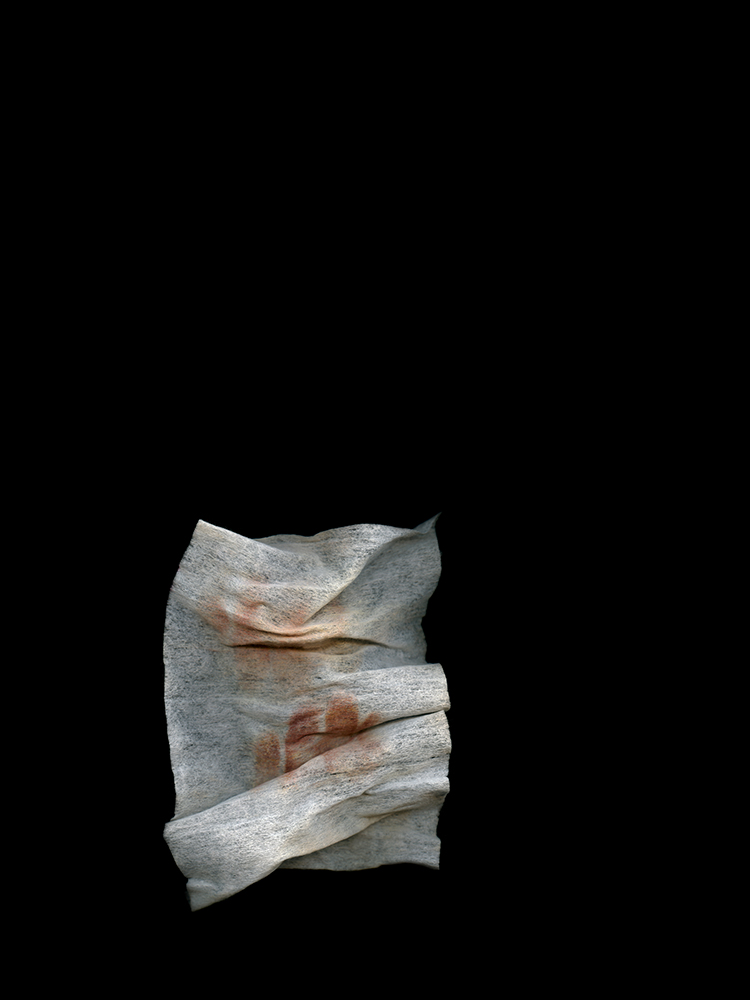

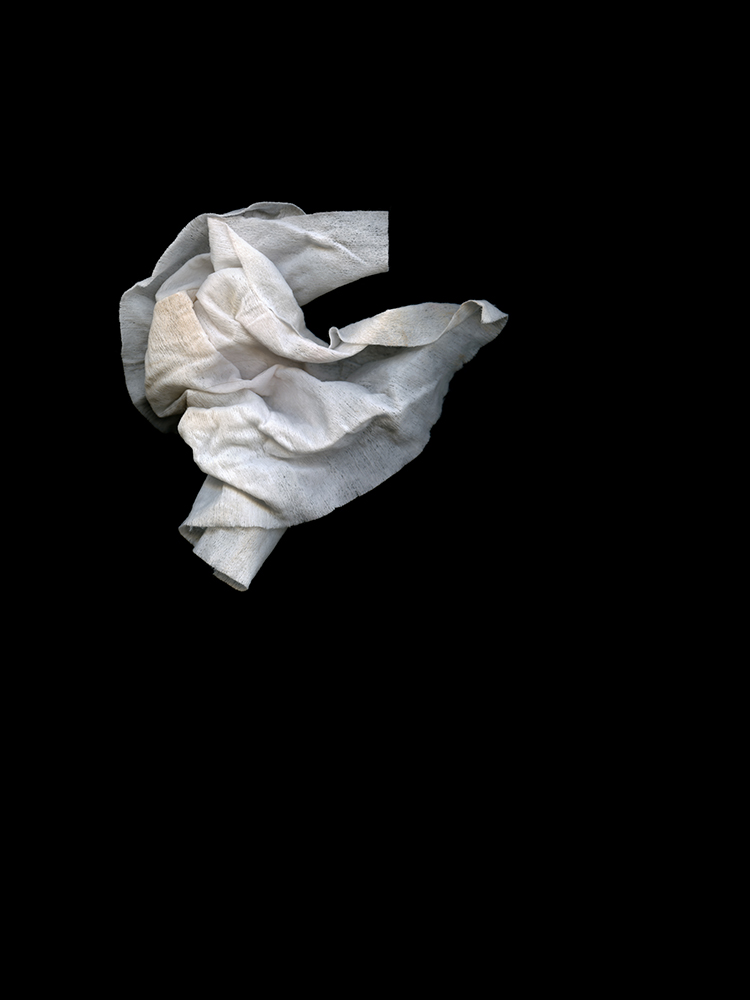

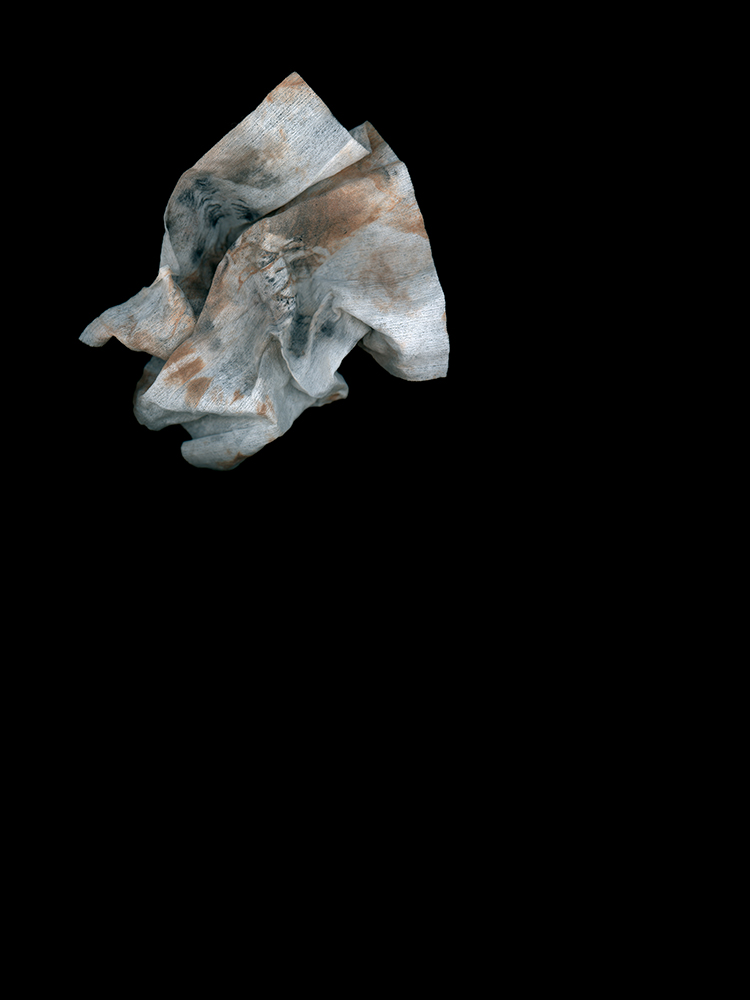

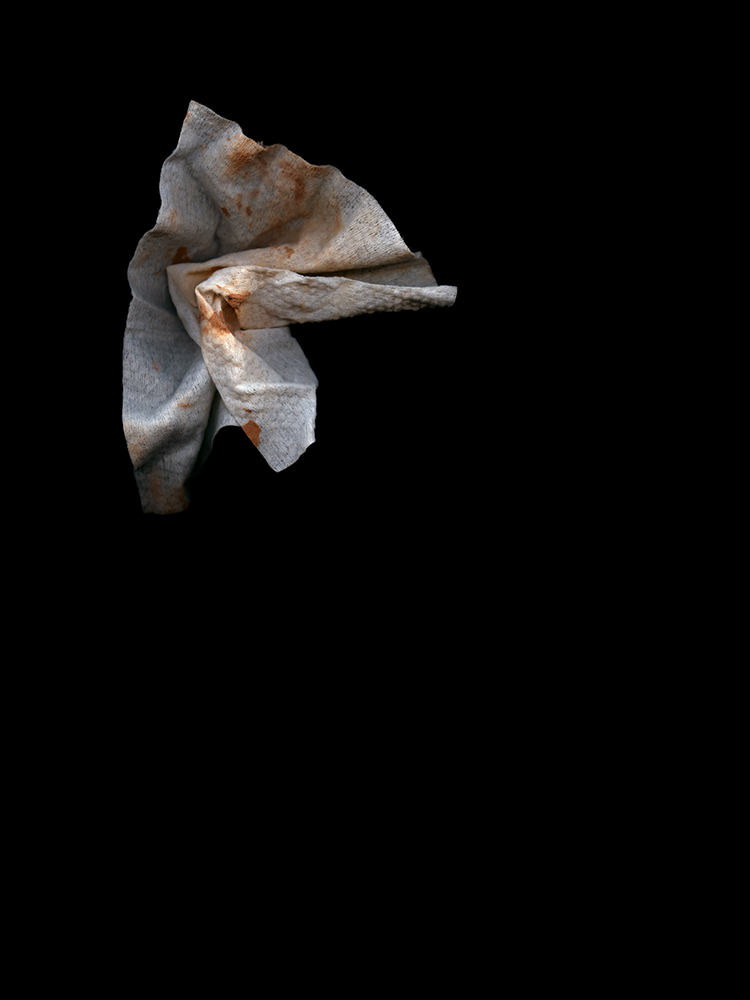

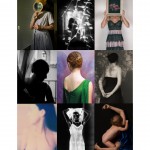

Second Skin takes away access to each model’s face and body to show the haunting reality of our emphasis on one’s outer shell. The feminine beauty ideal is a socially constructed belief that a woman’s appearance is her most important quality, which influences many women to strive to achieve an often-unobtainable visual perfection. Cosmetics can become a protective device, temporarily covering any self-perceived flaws, but cannot cure a dysmorphic perception of self that can lead to detrimental and destructive ends. The application of makeup in the morning and the removal at night is a daily ritual for many women. By collecting used makeup remover wipes from women, placing them back over the figure and photographing them, these images embody this repetitive beauty ritual.

Philosopher Paul Valéry stated that humans suffer from the “three body problem.” The first body is one humans inhabit and experience and the most important object we possess. The second body is the public façade, the figure we see in the mirror. The third body is the physical machine that we understand by thoroughly dissecting it under a microscope. Valéry argued that the second body causes humans the most distress. The subjects in these photographs are constrained under the wipes, and the body they inhabit is hidden; while the physical machine is restricted, and the public façade is altered. The shells of the figure created by the makeup wipes epitomize the tension between our outer body functioning as necessary protection and simultaneously being a tremendous source of angst and emotional pain. The smears of makeup left behind on the cloths are a metaphor for the internal struggle with body image. The markings often feel violent reflecting the relentless, brutal thoughts that many women have about their bodies on a daily basis. These remnants of old makeup, skin, stray eyelashes and hair display what many women put themselves through to avoid the discomfort, fear, and anxiety of appearing flawed.

Daniel George: Tell me about your interest in the “feminine beauty ideal,” and how it became the focus of your attention for this project.

Ashley Moog Bowlsbey: There was not one defining moment or event that directed my interest to the “feminine beauty ideal’’ but multiple experiences over time that added up and eventually bubbled to the surface. Growing up I watched many of my female family members and friends spend an hour each morning applying makeup and fixing their hair before they would leave the house or even open their front door. I wondered why women had to spend so much time performing these beauty rituals before they started their day but men did not. My mother was one of the few women in my life that did not wear makeup, so at first I never had an interest in wearing it either. Then from my high school years on, I was often asked, “Are you sick?”, or “Are you tired?”, which was then followed by the comment “You know you would be a lot prettier if you would just put on some makeup.” I was often called unfeminine or told I was a “tomboy” since I did not participate in traditionally feminine tasks. As if wearing makeup was what made you a woman. These remarks came from colleagues, friends and even strangers. I began believing them and feeling that I was not good enough if I did not take time in my morning routine to cover my skin in cosmetics.

Then right before graduate school, someone I am close to attempted suicide. They struggled their entire life with severe insecurities about their body image. And even though body image was not the reason for the suicide attempt, the fact that it was even a contributing factor to their extremely low sense of self-worth was devastating to me. Watching them fight this battle led me to question how the severity of body image issues were affecting other women’s lives. Though I never heard anyone openly expressing their insecurities or concerns about the pressures women face to look a certain way. I found that despite the importance placed on outward looks in today’s culture, publicly paying attention to or openly discussing physical appearance is often considered trivial. I was even told it was a trivial matter and that I should know better and be smarter than to struggle with such a thing. I questioned why I was falling into the trap of comparing myself to unrealistic standards of beauty. I am an educated woman; I should know better is what I told myself. I wondered, are there other women ashamed to admit their concerns about their faces, hair, and bodies for the same reason? Stifled by this fear that they would be told to stop being insecure or stop complaining. So I decided that I needed to make this series, to help myself work through my own struggle with body image and to let other women know they are not alone.

DG: The markings on these wipes are very gestural, and you write that they often feel violent. What prompted your use of these seemingly menial items as emblematic of the “repetitive beauty ritual?”

AMB: I had been experimenting and searching for the best way to make work addressing topics such as the feminine beauty ideal and internal battles with body image but I did not know how to present it visually. I went through many trials of photographing women without their makeup on, documenting the process of taking their makeup off, and photographing makeup packaging. I even went as far as breaking up makeup pigments and composing with the shattered pieces as a way of breaking down the beauty ideal. Though I did not believe any of it was working, I could not get any of my pieces to properly represent these intangible ideas of personal struggle, insecurity and vulnerability that I wanted to share. I needed something that would speak at a higher volume.

One day I was taking off my makeup at the end of the night and when I looked down at the makeup remover cloth in my hand with smears of red, brown and black makeup pigments I felt as if I was staring at all the insecurities and vulnerabilities I had been trying to cover up, and evidence of all of the struggles I had faced that day. The gestural markings felt like my own personal diary of the day, of these moments and emotions that only I get a glimpse of or experience. The markings left behind by the makeup made me think of wounds and scars. It was in that moment that I knew that this was what I had been searching for and it was what I needed to begin making work with to represent the metaphor of internal struggle. So I began making photographs of just the makeup remover cloths, studying the textures and markings. Then later moved into stitching them together and wrapping them around the female figures to further push the idea of repetition and ritual.

DG: You mention the daily, ritualistic procedure of applying and removing makeup—and makeup remover wipes play an obvious role in this exercise. Since your models are wrapped in a distinct fashion, I cannot help but draw parallels to the rituals and treatments of the mummification process, which were performed to preserve the integrity of the physical body after death. I imagine this had crossed your mind as you painstakingly wrapped each of your models. Could you speak more on the topic of ritual and how it played a role in the construction of these images?

AMB: Yes, they look very much like mummies, so the mummification process did cross my mind. It felt fitting since the use of cosmetics has been ingrained in human culture since Egyptian times. Though back then the use of makeup was more for protection from the elements and for rituals than it was to fit a standard. Though making them look like mummies was not my sole intent. I began wrapping the figures in their used makeup remover wipes in order to add a layer of repetition back into the work. Since the act of applying and removing makeup is ritualistic, I felt that the act of making the work also had to have a sense of ritual. To further this idea of repetition in the work, I created rituals for myself during the making process. For example, the act of collecting used makeup remover wipes from women, photographing each piece, then stitching them together and placing them back over the figure to photograph them again became my own personal ritual. Sewing is traditionally a feminine act, and has been a common practice for generations of women in my family. Stitching the pieces felt like a natural way to combine process and concept. It became a practical way of making it easier to wrap the figures as well as a way to add the traditions of my family into the series.

Since this series is an attempt at humanizing the psychological effects of the beauty ideal, and not an appeal to end the use of makeup. I believed that the work also needed to represent healing, especially since the healing process can be a ritual within itself. The texture of the used makeup remover cloths resemble bandages. They reminded me of the bandages that you would see on war victims or plastic surgery recovery patients. These portraits of women wearing their used makeup wipes symbolize the scars and flaws they see and feel, but that we are often unaware of. So the fragments of makeup, hair and skin left behind on these cloths were meant to symbolize the process of both struggle and healing. When we have a wound, we bandage it in order for it to heal. So the act of wrapping these women and laying out their internal struggles on the surface of the cloths, to me, was a way of addressing their issues in order to start their healing process.

DG: Your work is emotionally driven and confronts, among other things, loss and personal struggle. Why do you feel the photographic medium is the most appropriate means of communicating your personal vision on these topics?

AMB: Making art has always been a form of self-therapy for me or a way to share stories. There is something about picking up a camera and studying the structures, textures and colors around me that I find therapeutic. The process slows down my brain and relaxes me. As soon as I pick up a camera I feel grounded, and all of the thoughts or emotions that had been distracting me from tasks fade away. I am not sure if photography is the best way to communicate these specific topics but the medium has just always felt right for me and my process as an artist. I often find myself taking photographs as a way to work through personal things, and not with the intent for other people to actually see them. There are many photographs that I do not put out there. The ones that I do share, I hope that maybe the viewer can find a way to relate to them. I hope that maybe, just maybe, the images can help them too and if not hopefully they can enjoy the story that unfolds.

Then to address your question about photographing objects as surrogates for human experience, I have always been fascinated with what else could tell a person’s story other than just a photograph of them. Even before my interest in making work about body image, I never wanted my subject to be judged by what they look like. I do not want the viewer to form a narrative or opinion of the subject, based on stereotypes formed by one’s appearance. Especially in my early work, I enjoyed attempting to share the story of someone’s life through the things they surround themselves with, and the items they deem special enough to keep around for years. I think a lot about the stories and the history that objects have behind them but they can’t share with us. I enjoy the ambiguity of it, and that the viewer can begin to make their own narrative with the clues laid before them in my photographs

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Cheryle St. Onge: Calling the Birds HomeFebruary 23rd, 2026

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026