Photographers on Photographers: Paccarik Orue in conversation with Kevin Kunishi

Back in 2011 I was close to finishing my series There Is Nothing Beautiful Around Here, and I was hosting other photographers friends in my old apartment in the Mission District in San Francisco to share our projects to get some feedback. Someone asked me if he could invite Kevin Kunishi to our gathering, that he had just come back from Nicaragua where he had photographed a project about the collective memory of those who struggled with a decade long war between the socialists Sandinistas and the US backed Contras. When it was Kevin’s turn to share his work, he put down a huge stack of work prints and spread them on the table – I was blown away by the quality of the work and his humbleness. I could see why he was able to connect with the place and its people in such a wonderful and intimate way. We have become friends since then and I have been lucky to witness his dedication to the medium and growth.

Kevin Kunishi’s work has been recognized by numerous organizations and publications, including The New Yorker, The Sunday Telegraph, VICE, The California Sunday Magazine, Le Monde, American Photo Magazine, The International Photography Awards, Le Journal de la Photographie, AI-AP, The New York Photo Festival, Bloomberg Businessweek, Fast Company, Esquire, VISSLA, The Surfer’s Journal, Monocle, L’imparfaite, Scout Magazine, Pil Magazine, Allegra, Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazine, ONWARD, Photo District News, CENTER, Photolucida, CMYK magazine, Photographer’s Forum and Prix de la Photographie, Paris (PX3).

Kevin Kunishi’s work has been recognized by numerous organizations and publications, including The New Yorker, The Sunday Telegraph, VICE, The California Sunday Magazine, Le Monde, American Photo Magazine, The International Photography Awards, Le Journal de la Photographie, AI-AP, The New York Photo Festival, Bloomberg Businessweek, Fast Company, Esquire, VISSLA, The Surfer’s Journal, Monocle, L’imparfaite, Scout Magazine, Pil Magazine, Allegra, Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazine, ONWARD, Photo District News, CENTER, Photolucida, CMYK magazine, Photographer’s Forum and Prix de la Photographie, Paris (PX3).

His work has been exhibited widely both in the United States and internationally, at The Honolulu Museum of Art, Project Basho in Philadelphia, PA, Rayko Photo Center in San Francisco, CA, The Detroit Center for Contemporary Photography, V1 Gallery in Copenhagen, Denmark, Black & Blue Gallery in Brooklyn, New York, Interurban Gallery in Vancouver, Canada, The Hashtag Gallery in Toronto, Canada, Galerie Nowhere in Montreal, Canada, The Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C., The Daylight Project Space in Hillsborough, NC, Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong, Tai Kwun Contemporary in Hong Kong and The Bekman Gallery in New York.

In 2011 he was the honorary recipient of the Blue Earth Alliance Award for Best Photography Project, an award that honors projects that demonstrate excellence in the field of photography.

His first monograph, Los Restos de la Revolución, was released in the Fall of 2012 by Daylight Publishing, and was selected as one of Photo-Eye’s Best Books of 2012, and selected as one of PDN’s-2012 Indie Photo Books of The Year.

Paccarik Orue was born and raised in Lima, Peru and resides in the Bay Area, California where he earned a BFA from the Academy of Art University. His work has been shown at Blue Sky Gallery, SFO Museum, Jenkins Johnson Gallery, Book & Job Gallery, SF Camerawork and it has been featured in The New York Times, PDN, Juxtapox, KQED/PBS, among others. He was selected by PDN as one of the 30 Emerging Photographers to Watch in 2016 and has been awarded En Foco’s New Works Photography Fellowship Award (2013-2014.) Orue is the recipient of Duke University’s 2016 Archive of Documentary Arts Collection Award for Documentarians of Color. His first monograph, There Is Nothing Beautiful Around Here was published by Owl & Tiger Books in 2012.

Paccarik Orue – How did you get started with the work you made in Nicaragua? Why photographing there?

Kevin Kunishi – I have spent a lot of my undergraduate studies studying US foreign policy in places like Central America. With the camera I wanted to go down there and kind of go from the macro to the micro, interact and talk to people who were directly affected by those policies and the things that were unfolding. So I went with a camera and started networking in various villages along the Honduran border, living with families and recording interviews, making some photographs of what I was seeing, experiencing, navigating and collecting a lot of images and stories. I think when we met that one time I had quite a significant stack of photographs.

PO – And that is one of the things I admire about the way you work. The huge volume of images that you are then able to narrow down into a cohesive story speaks about your drive. I say that because I probably shoot one third of the images that you do out of fear of not being able to edit down later on. I also love your portraits and I am excited about the print trade we did…

PO – That portrait looks like a painting to me; the way you used the light falling on Omar’s hand…How did that image come about?

KK – It is mostly making use of the situation and elements that you are working with. At that time I was travelling with a Hasselblad and a tripod, a bunch of film and a light meter… and those mountains above the city of Jinotega, there is this ethereal mist that just blankets everything every morning and it comes back in the evening and paints everything in this beautiful diffused light.

PO – Since you photograph with film and were working in a remote area of Nicaragua, you did not have access to a processing lab, hence you could not see your progress as you were moving along with the project. How did that impact your work?

KK – I take a lot of notes, I journal constantly. And I think that with the Hasselblad for me, specially on a tripod, you only have 12 shots and you are hyper-focused on what is unfolding in front of you, so I carry many of the images with me for a while. In my head I kind of know what I’ve got and then when I get the film developed…there it is. I don’t get that with a digital format by the way. I see something in the viewfinder, and then I go look on the screen…and that’s not what I saw.

PO – Haha. The magic of film.

KK – I think is about knowing the film… you know what is going to do so you see it.

PO – On the day we met you shared a story about what you went through to try to preserve the film from heat and humidity. What did you have to do?

KK – If I was close to town there was a little shop with a freezer in the back, where all the Fantas and Cokes were being kept, so I left some film down there. And then out on the field, if I was going to be there for a while, I would try to find a shady place under the hut somewhere and bury it in a hole out of the sun in cooler dirt. I don’t know if it helped but I had convinced myself that it did.

PO – That is amazing. I’m sure it worked out, because you came back and the exposures on the film looked great…

KK – Thank you.

PO – By looking at the whole body of work, I think one key image in that series is Julio’s Cell at El Fortín. It is such a haunting image.

KK – I met Julio in the city of Leon. I was telling him what I was doing and he shared an experience with me. When he was twelve years old and he was coming back from baseball practice, his clothes were dirty and they grabbed him. They said that he was out in the bushes with the Sandinistas, so they threw him in this prison. There were two prisons in Leon. This one was in the outskirts of town and it was quite horrific. He took me there and showed me all around it, what was left of it. And he took me to the cell where he was in. The left and right sides are both in an angle, and about forty people were thrown in there. They would climb up on that side wall until their legs would give out and then they would switch. On one the corners there was a little hole, and that was the latrine. Forty inmates were all defecating and urinating in this small little three-inch hole and the smell was hideous.

PO – Looking at that image I could sense and feel everything you just described. When you face such situations, how do you handle those feelings during the image making process?

KK – It is an input/output dynamic, right? For me, when they are sharing information it provides context and depth to it. It gives you a lot more to think about; purpose behind the image while you are doing it and why you are doing it.

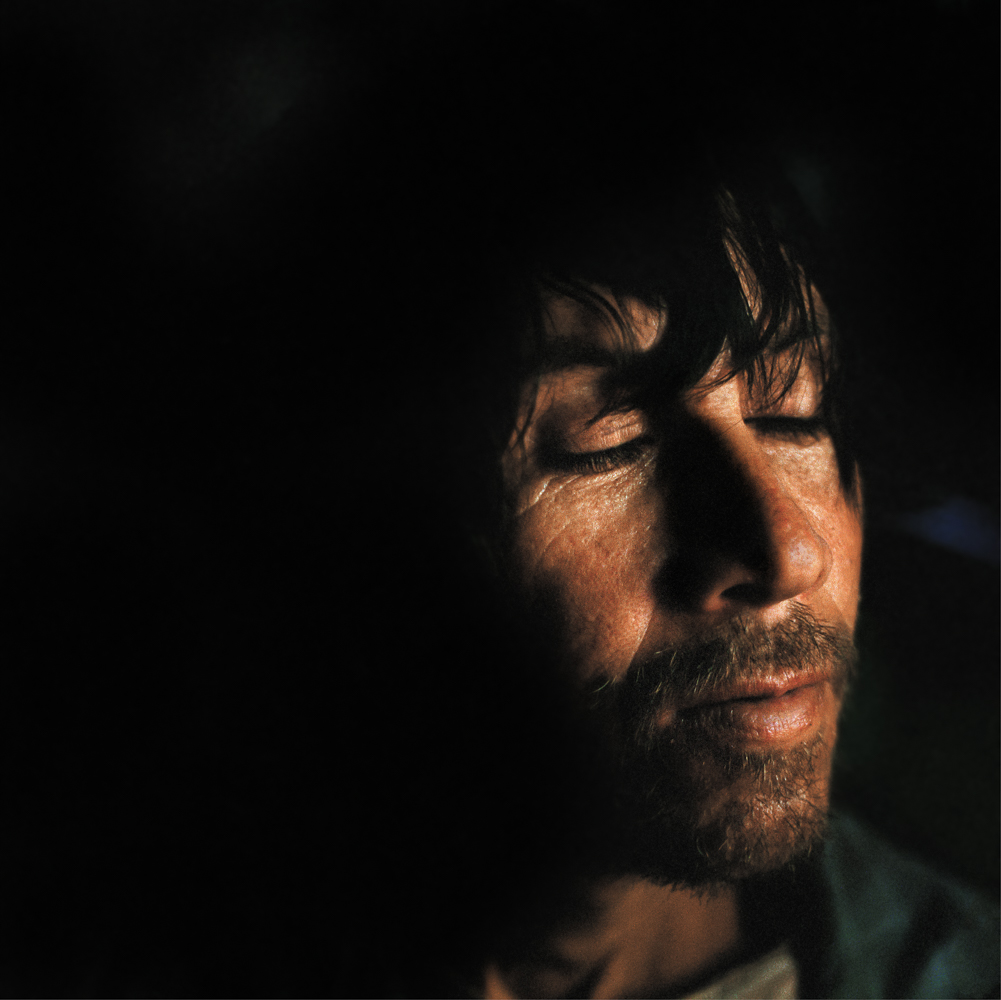

PO – In the portrait you made of Pedrito, the light comes from above in a subliminal way. He is looking up and out into the unknown and I feel the pain that he went through but I also feel hope. How do you work in moments like those? Did you take several images and then picked this one?

KK – I was taken out to this village -an area called Pentasma. Some people wanted me to meet him. We talked for about forty-five minutes and he told me his story. I took one or two portraits. He was wearing dark sunglasses the whole time and then he took them off. He said “If you really want to take my photo you should see me without my sunglasses”, and he took them off. There was this beautiful light coming through. The kitchens there, are made mostly of concrete blocks and they have about a six foot gap at the top between the roof and the wall, so the light at different times would pour in different directions and bounce around, so that is what is behind and the light comes down; but for me, in all these portraits, and all the work that I continue to do today, there is the idea of taking photographs and be given photographs… and this is one of those where I was given the gift of the image. I was not going to ask him to take off his sunglasses.

PO – It is amazing when photography works that way. The portrait you made of Juan is reminiscing of historic European paintings to me. Earlier you mentioned that you were carrying a tripod around. Was the tripod key for your in-door portraits?

KK – When I initially went down there I was photographing with an SLR and it had a big zoom. I would conduct these interviews and put that in someone’s face and I just felt horrible about the interaction. You think about the terminology we are using…you are shooting photos, you are taking photos, everything just felt a little aggressive. This is probably a mental exercise I was utilizing to find more comfort in it. So I switched to the Hasselblad and it slowed everything down. I put it on a tripod, you are looking down into the camera… it is a very slow process…a very focused process in that sense. During the interview, people were telling me these things and I could utilize from that to attempt to incorporate it intentionally into the portrait. He abducted people -that was his job during the war. So I wanted that hand emerging out of the darkness…

PO – After learning about your process the energy that the portrait of Juan emanates is even stronger. To me it is almost as if he went back to those days…and you made the portrait while he was revisiting those thoughts and feelings -amazing. It is a constant thread in your portraiture in this series. Then you take the viewer from darkness to lightness with the portrait of Nelita. As you mentioned, I can see the effect that your previous conversations and interactions with your subjects are having in the final image. The same with Raul’s AK 47 portrait and all the other ones; they are back to those difficult times and you made their portraits in that state of mind. Everything came together in that series. You were collecting experiences, fragments from a time long gone but that it stills haunts the people who went through it. The title of your project Los restos de la revolución could not have been any better.

PO – I think your book is aging really well. As time passes by, what do you feel your contribution to saving the memory of the people who went through this is going to be like?

KK – I had never thought of it in that context. This book is a document of that experience. From the sales of prints and various things, we managed to send money down there for various organizations that can help people with psychological counseling, among other things. That is how I visualized the end game of this body of work. It is out there and it is a document. It has happened to these people…

PO – I am so glad you worked on it. Often times, communities are easily overlooked and it takes an act of strength, curiosity and kindness to make connections the way you did there. I congratulate you because I think it paid off –it became such a strong body of work that is already aging so well and that in the future it will be an important document to look back to.

KK – Thank you.

PO – You have a direct history with Hawaii, right?

KK – Yes, my family is from there.

PO – Does that influence the way you work on your project Imi Haku?

KK – Yeah, it brought me back there to explore some things about my own personal history, my family history that I didn’t know about. My parents passed away when I was pretty young. I spent ten, fifteen years taking care of my grandparents. I spent most of my twenties over there and I wanted to dive into that -my family history there. A lot of these places in the images have to do with that. I would go through these situations in areas that were important to my family or my father, interview people in these communities, collect their stories, constantly connecting these notes that I sequenced, and continue to sequence. This body of work has been going on for a very long time.

PO – Yeah, I have seen you work on this for a very long time. Where is the project at this moment?

KK – When I was working on it, my wife and I had our first baby, and we had to move to the Philippines and stayed there for almost three years. I started focusing on three other projects that I am really concentrating on, but now that we are back in the US, I will come back to it. I still have thousands of negatives that I have to look at again. You know, I like to step away and come back to it -to severe the personal connections and re-establish them and start playing with images in that way, if that makes sense.

PO– Yes, it does. Thanks so much for talking to me and telling us more about you and your work

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

J. Lester Feder: The Queer Face of WarMarch 11th, 2026

-

L. Kasimu Harris: New Photography 2025: Lines of Belonging at MOMAMarch 10th, 2026

-

Kiana Hayeri: No Woman’s LandMarch 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026