Nicole Jean Hill: Lora Webb Nichols Archive

Projects featured this week were selected from our most recent call-for-submissions. I was able to interview each of these artists to gain further insight into the bodies of work they shared. Today, we are speaking with Nicole Jean Hill about the Lora Webb Nichols Archive.

With an anthropological approach to image making, Nicole Jean Hill is an artist using photography and video to explore familiar spaces and activities within the American cultural and natural landscape. She was born and raised in Toledo, Ohio and received a BFA in photography from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and an MFA in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her photographs have been exhibited throughout the U.S., Europe, Canada and Australia, including Gallery 44 in Toronto, the Australia Centre for Photography in Sydney, and the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been featured in the Magenta Foundation publication Flash Forward: Emerging Photography from the U.S., U.K., and Canada, the Humble Art Foundation’s The Collector’s Guide to Emerging Photography, and National Public Radio. Hill has been an artist-in-residence at several arts organizations and universities including the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Wendover, Utah, the Ucross Foundation in Wyoming, and the Newspace Center for Photography in Portland, Oregon. She currently resides in Eureka, California and is a Professor of Art at Humboldt State University and the co-curator of the Lora Webb Nichols Archive.

A selection of photographs from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive will be on display at the Art Gallery of Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs, WY from September 17 – November 5, 2021, and at the Hungarian House of Photography Project Space, in Budapest, Hungary from April 27- June 5, 2022. A publication of Nichols’ work, Encampment, Wyoming: Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive 1899-1948, as well as prints from the archive, are available for purchase on the Lora Webb Nichols Archive website.

Lora Webb Nichols Archive

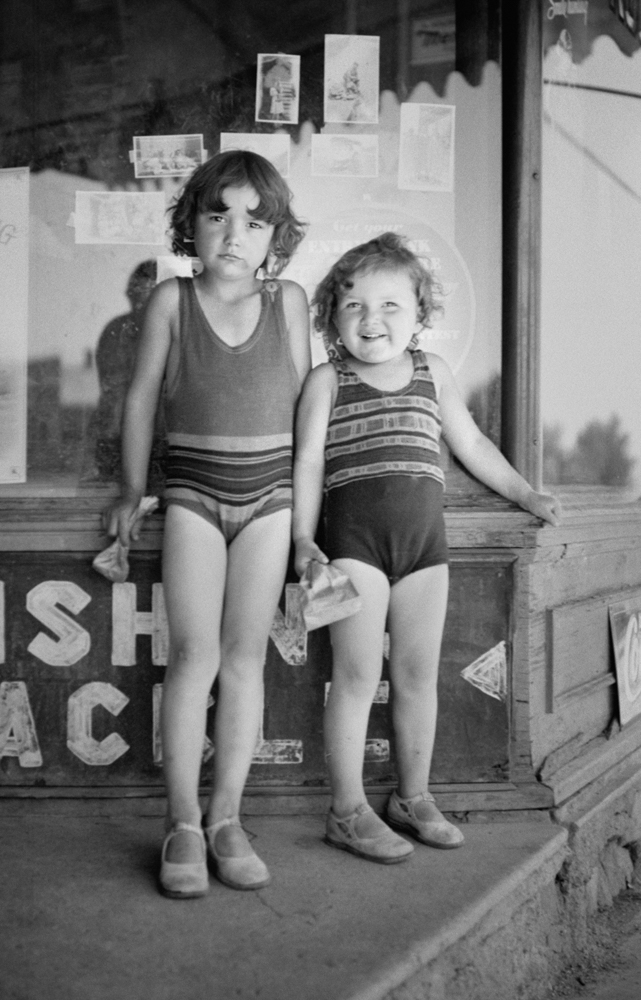

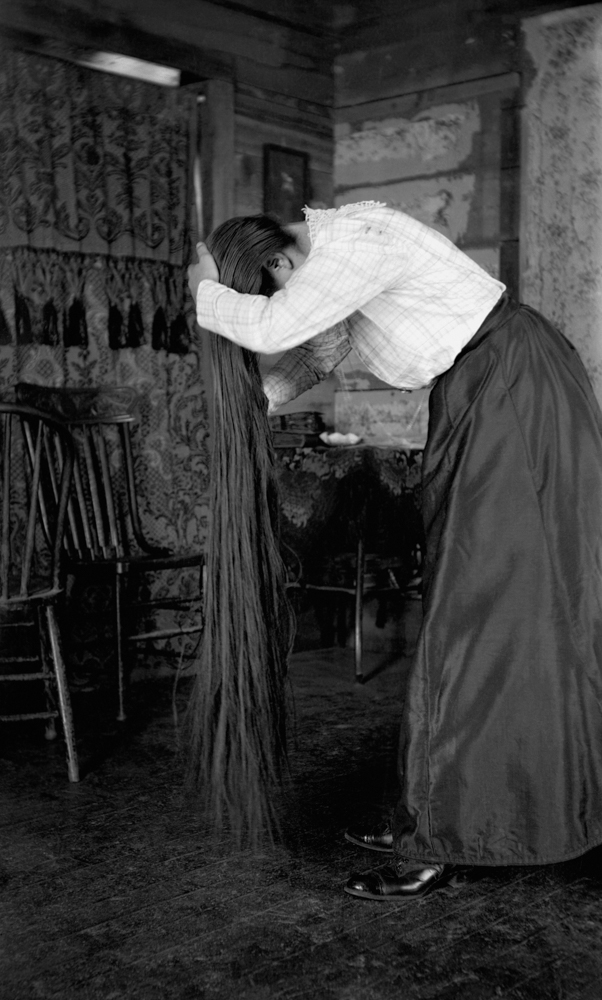

Lora Webb Nichols (1883-1962) created and collected approximately 24,000 negatives over the course of her lifetime in the mining town of Encampment, Wyoming. The images chronicle the domestic, social, and economic aspects of the sparsely populated frontier of south-central Wyoming.

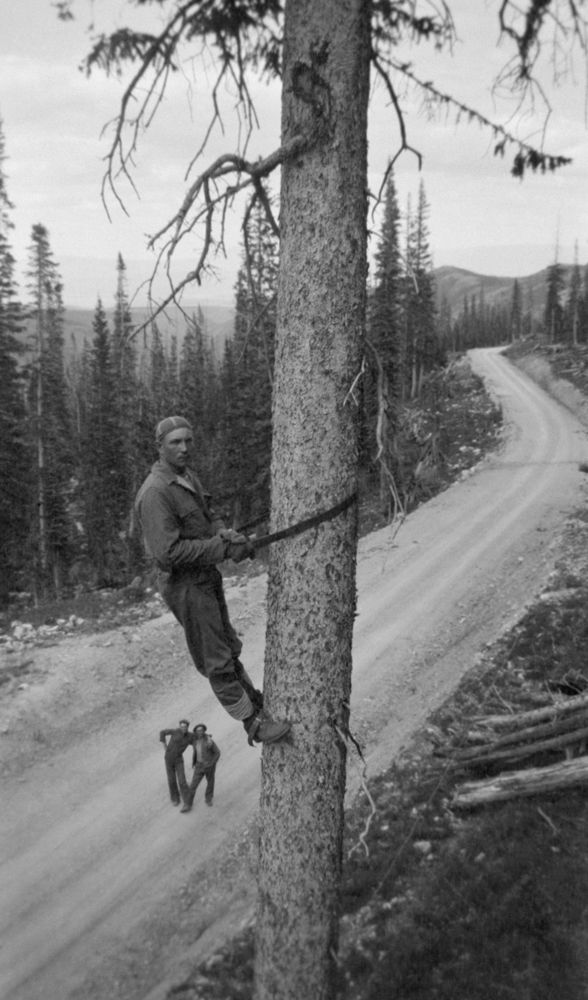

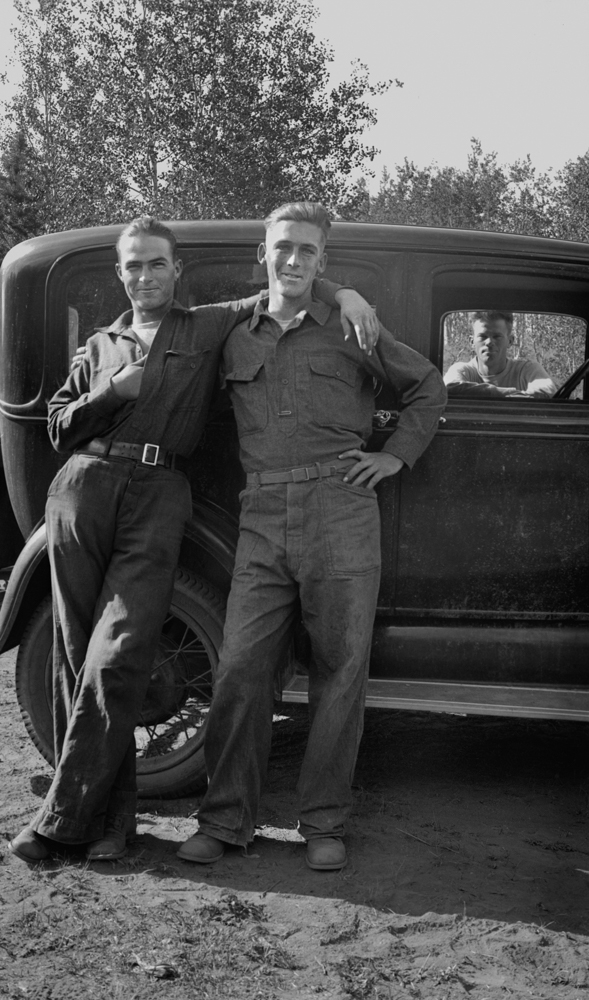

Nichols received her first camera in 1899 at the age of 16, coinciding with the rise of the region’s copper mining boom. The earliest photographs are of her immediate family, self-portraits, and landscape images of the cultivation of the region surrounding the town of Encampment. In addition to the personal imagery, the young Nichols photographed miners, industrial infrastructure, and a small town’s adjustment to a sudden, but ultimately fleeting, population increase.

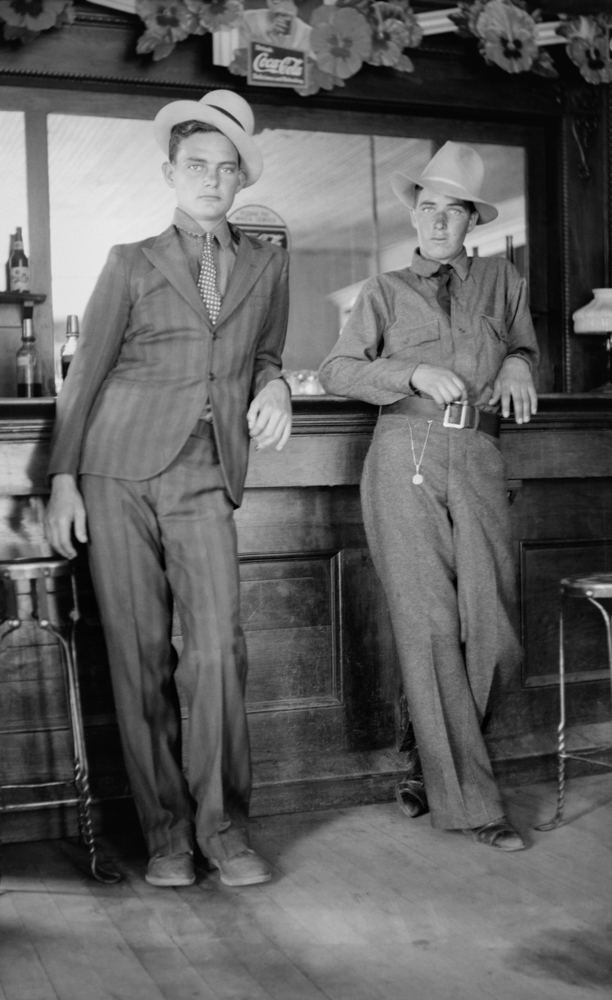

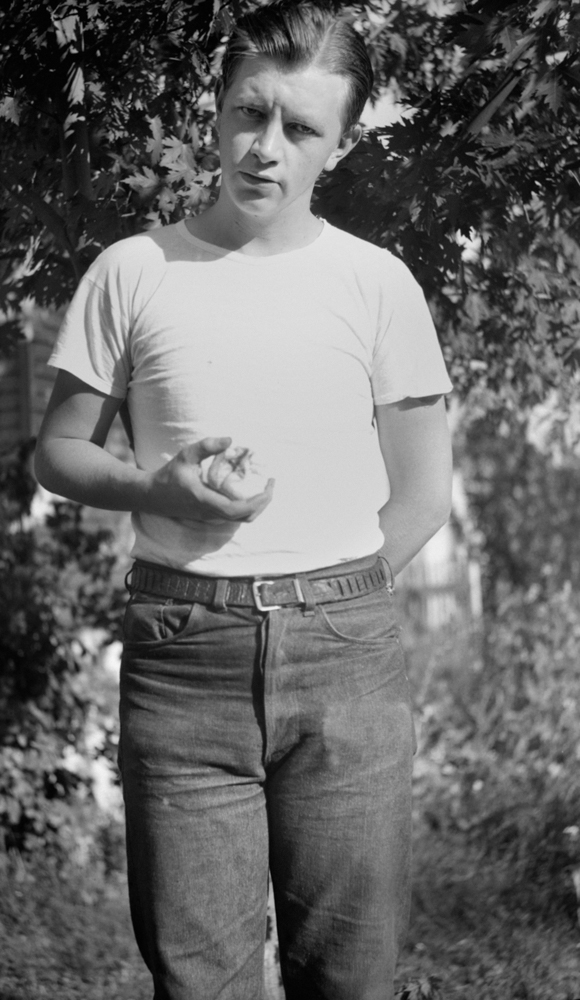

As early as 1906, Nichols was working for hire as a photographer for industrial documentation and family portraits, developing and printing from a darkroom she fashioned in the home she shared with her husband and their children. After the collapse of the copper industry, Nichols remained in Encampment and established the Rocky Mountain Studio, a photography and photofinishing service, to help support her family. Her commercial studio was a focal point of the town throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Daniel George: How did you come across the work of Lora Webb Nichols, and what was it about her and her imagery that attracted your attention—enough to dedicate your time and energy to bring awareness to her massive archive of photographs?

Nicole Jean Hill: I learned of the existence of Lora’s work while I was at an artist residency program near Encampment, Wyoming in 2012. Although I heard the basic specs through the Grand Encampment Museum’s website- that there was an archive of 24,000 images by a female photographer who started photographing at the age of 16- I didn’t know much else. I was able to learn more of the backstory through writings about and by Lora before I could see the images, which made the prospect of what the photographs actually contained even more intriguing. Through the process of trying to learn more and see the actual photographs, I discovered that they were in limbo and not easily accessible to the public. I connected with Nancy Anderson, the caretaker of the collection, and spent the next few years helping her resolve the technical challenges of making a collection of that size publicly accessible. It was only after those hurdles were addressed that I was actually able to dive into the content of the photographs. Much of the time and energy I spent was a leap of faith that it was a collection worth working on. I figured…how could it not be worth the effort with just the little info I had? Given the time frame and Lora’s bio, I guessed that it had to be a treasure trove. I didn’t anticipate, though, that it would be as rich and complex as it turned out to be.

DG: 24,000 negatives is a lot to cull from when curating an exhibition. I’m curious about that process—how did you begin, and what were you looking for in terms of creating a representative sample of her work?

NJH: I first started by just looking through the whole archive a few times. Then I went back through and narrowed it down to about 2,000 photographs that were aesthetically interesting on some level and free from major technical problems. In reading through Lora’s diaries and learning more about her story, I identified three major unique themes in the photographs. This included her images of the community of girls and women she was close with and photographed throughout her life, the portraits she made of friends and strangers from the mid-1920s to the late-1930s when she ran the Rocky Mountain Studio, and the images she collected from other people through her role as a photofinisher. In preparing her work for the website, book and exhibition, I wanted to include sufficient representation from each of these three themes.

DG: I am fascinated by Nichols’ perspective as a woman on the American frontier in the early 20th century, and how she produced what you describe as a “unique window into the role of women and their cultivation of community in this era.” Could you talk more about the significance of this?

NJH: On the surface level, Lora was making photographs in a community in which the men worked in the mines and as loggers, and the women maintained the homesteads. Doing so in a geographically isolated place created really close bonds between the women. Lora photographed all aspects of their lives, including the day-to-day chores of maintaining the home and land. Also, these photographs (although this is just my speculation), were not meant for anyone but their own close-knit group. The subjects often don’t look like they are posing for the camera, they are looking at Lora. The images appear free of the artifice of the act of picture making- and so we see through the photograph in a way. I think the intimate comfort level Lora had with her community allowed the camera to be a more passive factor in the equation. Because of these two things, Lora’s circumstances and the way the camera was incorporated seamlessly into her life, the photographs document these self-sufficient women in a very compelling way.

DG: As an image maker in your own right, how has the study and curation of Nichols’ work influenced your creative practice?

NJH: I can’t recognize at the moment how Lora’s photographs have influenced my own creative practice, although maybe in time I will understand that better. But I reflected about photography practice more broadly through trying to understand the trajectory of her life and how photography played a role in it. She went through incredibly productive phases of making work, and periods where other things overtook her time and energy. Yet photography punctuated her life steadily for 63 years. When I get overwhelmed with things that pull my attention away from my own art practice (like working on this archive!), I feel at peace knowing that things will circle back around when it is time and that periods of greater and lesser artistic productivity are okay.

DG: So, there is an exhibition of Nichols’ photographs that is currently traveling throughout the United States, and will go international next year. On top of that, there is a book that was recently published. What else do we have to look forward to with Lora Webb Nichols?

NJH: I was really struck by an essay I recently read in A Year in the Art World by Matthew Israel about the curator of the Peter Hujar estate, Stephen Koch. He makes the point that an archive doesn’t just appear in the world and then have its own trajectory. It requires continual work by archive caretakers and curators to make sure these artists who were overlooked for one reason or another during their own lifetime stay a part of the conversation going forward. So I look forward to finding more venues for the exhibition and plan to continue to advocate for Lora’s work to expand what the history of photography looks like. The book Encampment, Wyoming: Selection from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive 1899-1948 (FW Books) functions as a greatest hits introduction and is just the tip of the iceberg of what is possible to share about this woman’s incredible life story. The website (www.lorawebbnichols.org) will have updates when Nancy Anderson and I have more things to share about the collection! We are both really excited to also see how other people interact with Lora’s work and hope to see the archive used for research into a broad range of topics.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 2February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 3February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 LOVE Exhibition, Part 4February 14th, 2026

-

The 2026 Lenscratch New Beginnings Exhibition (Part II)January 31st, 2026

-

South Korea Week: Sung Nam Hun: The Rustling Whispers of the WindJanuary 16th, 2026